Swiss Guards

Swiss Guards (French: Gardes Suisses; German: Schweizergarde) are the Swiss soldiers who have served as guards at foreign European courts since the late 15th century.

The earliest Swiss guard unit to be established on a permanent basis was the Hundred Swiss (Cent Suisses), which served at the French court from 1490 to 1817. This small force was complemented in 1616 by a Swiss Guards regiment. In the 18th and early 19th centuries several other Swiss Guard units existed for periods in various European courts.

Foreign military service was outlawed by the revised Swiss Federal Constitution of 1874, with the only exception being the Pontifical Swiss Guard (Latin: Pontificia Cohors Helvetica, Cohors Pedestris Helvetiorum a Sacra Custodia Pontificis; Italian: Guardia Svizzera Pontificia) stationed in Vatican City. The modern Papal Swiss Guard serves as both a ceremonial unit and a bodyguard. Established in 1506, it is one of the oldest military units in the world. It is also the smallest army in the world.[1]

In France

There were two different corps of Swiss mercenaries performing guard duties for the Kings of France: the Hundred Swiss (Cent Suisses), serving within the Palace as essentially bodyguards and ceremonial troops,[2] and the Swiss Guards (Gardes Suisses), guarding the entrances and outer perimeter. In addition the Gardes Suisses served in the field as a fighting regiment in times of war.[3]

Hundred Swiss (Cent Suisses)

The Hundred Swiss were created in 1480 when Louis XI retained a Swiss company for his personal guard.[4]

By 1496 they comprised one hundred guardsmen plus about twenty-seven officers and sergeants. Their main role was the protection of the King within the palace as the garde du dedans du Louvre (the Louvre indoor guard), but in the earlier part of their history they accompanied the King to war. In the Battle of Pavia (1525) the Hundred Swiss of Francis I of France were slain before Francis was captured by the Spanish. The Hundred Swiss shared the indoor guard with the King's Bodyguards (Garde du Corps), who were Frenchmen.[5]

The Hundred Swiss were armed with halberds, the blade of which carried the Royal arms in gold, as well as gold-hilted swords. Their ceremonial dress as worn until 1789 comprised an elaborate 16th century Swiss costume covered with braiding and livery lace. A less ornate dark blue and red uniform with bearskin headdress was worn for ordinary duties.[6]

The Cent Suisses company was disbanded after Louis XVI of France left the Palace of Versailles in October 1789. It was, however, refounded on 15 July 1814 with an establishment of 136 guardsmen and eight officers. The Hundred Swiss accompanied Louis XVIII into exile in Belgium the following year and returned with him to Paris following the Battle of Waterloo. The unit then resumed its traditional role of palace guards at the Tuileries but in 1817 it was replaced by a new guard company drawn from the French regiments of the Royal Guard.[7]

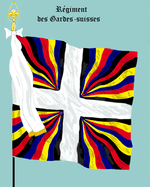

Swiss Guards (Gardes Suisses)

In 1616, Louis XIII of France gave an existing regiment of Swiss infantry the name of Gardes suisses (Swiss Guards). The new regiment had the primary role of protecting the doors, gates and outer perimeters of the various royal palaces.[8]

By the end of the 17th century the Swiss Guards were formally part of the Maison militaire du roi.[9] As such they were brigaded with the Regiment of French Guards (Gardes Françaises), with whom they shared the outer guard, and were in peace-time stationed in barracks on the outskirts of Paris. Like the eleven Swiss regiments of line infantry in French service, the Gardes suisses wore red coats. The line regiments had black, yellow or light blue facings but the Swiss Guards were distinguished by dark blue lapels and cuffs edged in white embroidery. Only the grenadier company wore bearskins while the other companies wore the standard tricorn headdress of the French infantry.[10]

During the 17th and 18th centuries the Swiss Guards maintained a reputation for discipline and steadiness in both peacetime service and foreign campaigning. Their officers were all Swiss and their rate of pay substantially higher than that of the regular French soldiers.[11]

The Guards were recruited from all the Swiss cantons. The nominal establishment was 1,600 men though actual numbers normally seem to have been below this.[12]

During the Revolution

The most famous episode in the history of the Swiss Guards was their defence of the Tuileries Palace in central Paris during the French Revolution. Of the nine hundred Swiss Guards defending the Palace on 10 August 1792, about six hundred were killed during the fighting or massacred after surrender. One group of sixty Swiss were taken as prisoners to the Paris City Hall before being killed by the crowd there.[13] An estimated hundred and sixty more died in prison of their wounds, or were killed during the September Massacres that followed. Apart from less than a hundred Swiss who escaped from the Tuileries, some hidden by sympathetic Parisians, the only survivors of the regiment were a three-hundred-strong[14] detachment that had been sent to Normandy to escort grain convoys a few days before 10 August.[15] The Swiss officers were mostly amongst those massacred, although Major Karl Josef von Bachmann in command at the Tuileries was formally tried and guillotined in September, still wearing his red uniform coat. Two Swiss officers, the captains Henri de Salis and Joseph Zimmermann, did however survive and went on to reach senior rank under Napoleon and the Restoration.[15]

There appears to be no truth in the charge that Louis XVI caused the defeat and destruction of the Guards by ordering them to lay down their arms when they could still have held the Tuileries. Rather, the Swiss ran low on ammunition and were overwhelmed by superior numbers when fighting broke out spontaneously after the Royal Family had been escorted from the Palace to take refuge with the National Assembly. A note has survived written by the King ordering the Swiss to retire from the Palace and return to their barracks but this was only acted on after their position had become untenable. The regimental standards had been secretly buried by the adjutant shortly before the regiment was summoned to the Tuileries on the night of 8/9 August, indicating that the likely end was foreseen. They were discovered by a gardener and ceremoniously burned by the new Republican authorities on 14 August.[16] The barracks of the Guard at Courbevoie were stormed by the local National Guard and the few Swiss still on duty there also killed.[15]

The heroic but futile[13] stand of the Swiss is commemorated by Bertel Thorvaldsen's Lion Monument in Lucerne, dedicated in 1821, which shows a dying lion collapsed upon broken symbols of the French monarchy. An inscription on the monument lists the twenty-six Swiss officers who died on 10 August and 2–3 September 1792, and records that approximately 760 Swiss Guardsmen were killed on those days.[17]

Following the Restoration

The French Revolution abolished mercenary troops in its citizen army, but Napoleon and the Bourbon Restoration both made use of Swiss troops. Four Swiss infantry regiments were employed by Napoleon, serving in both Spain and Russia. Two of the eight infantry regiments included in the Garde Royale from 1815 to 1830 were Swiss and can be regarded as successors of the old Gardes suisses. When the Tuileries was stormed again, in the July Revolution (29 July 1830), the Swiss regiments, fearful of another massacre, were withdrawn or melted into the crowd. They were not used again. In 1831 disbanded veterans of the Swiss regiments and another foreign unit, the Hohenlohe Regiment, were recruited into the newly raised French Foreign Legion for service in Algeria.[18]

Swiss in other armies

Swiss Guard units similar to those of France were in existence at several other Royal Courts at the dates indicated below:

- From 1579 on, a Swiss Guard served the House of Savoy, rulers of Savoy and later the Kingdom of Sardinia. The Guard was dissolved in 1798.[19]

- From 1696 to 1713, a Swiss Guard served at the court of Frederick I of Prussia.[20]

- a Cent-Suisse unit was in existence from 1730 until 1757 and again from 1763 to 1814 in the Kingdom of Saxony.[21]

- From 1748 until 1796, a company of Swiss (Cent-Suisses) served as a personal guard for the Stadhouder of the Dutch Republic; besides a Dutch Guard Regiment, there was also a Swiss Guards Regiment from 1749 to 1796.[22]

In addition to small household and palace units, Swiss mercenary regiments have served as regular line troops in various armies; notably those of France[23], Spain[24] and Naples[25] (see Swiss mercenaries).

Swiss constitutional prohibition

The Swiss constitution, as amended in 1874, forbade all military capitulations and recruitment of Swiss by foreign powers,[26] although volunteering in foreign armies continued until prohibited outright in 1927. The Papal Swiss Guard (see above) remains an exception to this prohibition, reflecting the unique political status of the Vatican and the bodyguard-like role of the unit.

In popular culture

When writing Hamlet, Shakespeare assumed (perhaps relying on his sources) that the royal house of Denmark employed a Swiss Guard: In Act IV, Scene v (line 98) he has King Claudius exclaim "Where are my Switzers? Let them guard the door".[27] However, it may also be due to the word "Swiss" having become a generic term for a royal guard in popular European usage. Coincidentally, the present-day gatekeepers of the royal palace of Copenhagen are known as schweizere, "Swiss".[28]

References

- Cutler, Nellie (2011). "Italy, Malta, San Marino, and Vatican City". TIME for Kids World Atlas. TIME for Kids Books (Rev. and updated ed.). New York, NY. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-60320-884-0.

- Funcken, Liliane et Fred. L'Uniforme et les Armes des Soldats de la Guerre en Dentelle 1. pp. 16–17. ISBN 2-203-14315-0.

- Funcken, Liliane et Fred. L'Uniforme et les Armes des Soldats de la Guerre en Dentelle 1. pp. 38–41. ISBN 2-203-14315-0.

- Rene Chartrand: Louis XV's Army – Foreign Infantry p.3; ISBN 1-85532-623-X

- Mansel, Philip. Pillars of Monarchy. An Outline of the Political and Social History of Royal Guards 1400-1981. pp. 2–9. ISBN 0-7043-2424-5.

- Funcken, Liliane et Fred. L'Uniforme et les Armes des Soldats de la Guerre en Dentelle 1. p. 17. ISBN 2-203-14315-0.

- Liliane et Fred Funcken: "L'Uniforme et les Armes des Soldats de La Guerre en Dentelle"; ISBN 2-203-14315-0

- Mansel, Philip. Pillars of Monarchy. p. 9. ISBN 0-7043-2424-5.

- Davin, Dieder. The Allied Swiss Troops in French Service. p. 7. ISBN 978-2-35250-235-7.

- Funcken, Liliane et Fred. L'Uniforme et les Armes des Soldats de la Guerre en Dentelle 1. pp. 39–41. ISBN 2-203-14315-0.

- Tozzi, Christopher J. Nationalizing France's Army. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-8139-3833-2.

- General Pierre Bertin, page 84 "Le Fantassin de France", Service Historique de l'Armee de Terre, B.I.P. Editions 1988

- M.J Sydenham, page 111, "The French Revolution", B. T. Batsford Ltd, 1965

- Philippe, Louis-. Memoirs 1773-1791. p. 247. ISBN 0-15-158855-4.

- Jerome Bodin, page 259, "Les Suisses au Service de la France", ISBN 2-226-03334-3

- Davin, Didier. Officers and Soldiers of Allied Swiss Troops in French Service 1785-1815. p. 7. ISBN 978-2-35250-235-7.

- "Lion Monument Inscriptions". Glacier Garden, Lucerne. Retrieved 8 August 2008.

- Porch, Douglas. The French Foreign Legion. A complete History. pp. 3, 4, 14. ISBN 0-333-58500-3.

- Mansel, Philip. Pillars of Monarchy. An Outline of the Political and Social History of Royal Guards 1400-1981. pp. 7&16. ISBN 0-7043-2424-5.

- Mansel, Philip. Pillars of Monarchy. An Outline of the Political and Social History of Royal Guards 1400-1981. p. 159. ISBN 0-7043-2424-5.

- Mansel, Philip. Pillars of Monarchy. An Outline of the Political and Social History of Royal Guards 1400-1981. p. 16. ISBN 0-7043-2424-5.

- van Hoof, Joep. Pillars of Monarchy. Military Uniforms in the Netherlands 1752-1800. p. 136. ISBN 978-3-902526-49-6.

- Chartrand, Rene. Louis XV's Army (3). Foreign Infantry. p. 6. ISBN 1-85532-623-X.

- Rene Chartrand, page 20, "Spanish Army of the Napoleonic Wars 1793–1808", ISBN 1-85532-763-5

- Giorgio Franzosi, page 51 "L'Esercito delle Due Sicile", Rivista Militare 1987

- Bundesverfassung, Constitution fédérale, 29 May 1874, AS 1, RO 1 [BV 1874, Cst 1874] art. 11 (Switz.).

- Philip Haythornthwaite, page 85 "The French Revolutionary Wars 1789–1802", ISBN 0-7137-0936-7

- "Obituary of former "Swiss" Henry A. Ulstrup". Kristeligt Dagblad (in Danish). 28 July 2009. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

The Swiss (Schweizeren) were at that time doormen at the royal palaces and thus the first to receive the royal family's private and official guests.

- Henry, P.: Gardes suisses in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland, 2005-06-08.

- Bodin, J.: Les Suisses au Service de la France; Editions Albion Michael, 1988. ISBN 2-226-03334-3.

- Bertin, P.: Le Fantassin de France; Service Historique de L'Armee de Terre, 1988.

- Philip Mansel, Pillars of Monarchy: An Outline of the Political and Social History of Royal Guards 1400–1984, ISBN 0-7043-2424-5

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Swiss Guards. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Swiss soldiers in foreign service. |