Snuff bottle

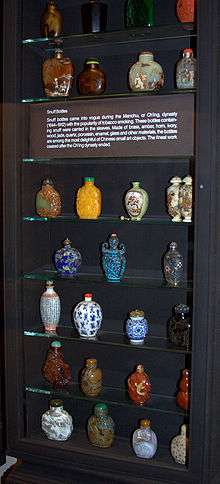

Snuff bottles were used by the Chinese, Mongolians during the Qing Dynasty to contain powdered tobacco. Smoking tobacco was illegal during the Qing Dynasty, but the use of snuff was allowed because the Chinese considered snuff to be a remedy for common illnesses such as colds, headaches and stomach disorders. Therefore, snuff was carried in a small bottle like other medicines. The snuff bottle replaced the snuff box used by Europeans.

History

Tobacco was introduced by the Portuguese to the court at Beijing some time during the mid- to late-16th century. It was originally smoked in pipes before the establishment of the Qing Dynasty. The use of snuff and snuff bottles spread through the upper class, and by the end of the 17th century it had become a part of social ritual to use snuff. This lasted through most of the 18th century. Eventually, the trend spread into the rest of the country and into every social class. It was common to offer a pinch of snuff as a way to greet friends and relatives. Snuff bottles soon became an object of beauty and a way to represent status and wealth.

The use of snuff increased and decreased with the rise and fall of the Qing Dynasty and died away soon after the establishment of the Republic of China. However, contemporary snuff bottles are still being made, and can be purchased in souvenir shops, flea markets and museum gift shops. Original snuff bottles from the Qing period are a desirable target for serious collectors and museums. A good bottle has an extra quality over and above its exquisite beauty and value: that is touch. Snuff bottles were made to be held and so, as a rule, they have a pleasant tactile quality.

Materials and sizes

The size of a snuff bottle is small enough to fit inside the palm. Snuff bottles were made out of many different materials including porcelain, jade, rhinoceros horn, ivory, wood, tortoiseshell, metal and ceramic, though probably the most commonly used material was glass. The stopper usually had a very small spoon attached for extracting the snuff. Though rare, such bottles were also used by women in Europe in Victorian times, with the bottles typically made of cut glass.[1]

Chinese snuff bottles were typically decorated with paintings or carvings, which distinguished bottles of different quality and value. Decorative bottles were, and remain, time-consuming in their production and are thus desirable for today's collectors.

Symbolism in snuff bottle decoration

Many bottles are completely devoid of decoration, others are incredibly ornate. As in all Chinese arts and crafts, motifs and symbols play an important part in decorative detail. Symbols are derived from a multitude of sources such as legends, history, religion, philosophy and superstition. The ideas used are almost always directed toward bringing wealth, health, good luck, longevity, even immortality to the owner of an artifact, frequently as a wish expressed in a kind of coded form by the giver of a gift. Probably the most popular decoration is the Shou character, a symbol of happiness and longevity, illustrated at right. Shou or Sau was one of Three Star Gods.

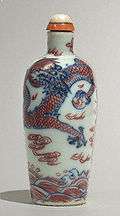

Another popular device is a representation of the 18 Lohan, who were the personal disciples of Buddha, just one group of the many revered immortals in China. Apart from the 18 Lohan there is a constellation of other divines who are portrayed, even their innards. The eight precious organs of the Buddha are venerated – his heart, gall bladder, spleen, lungs, liver, stomach, kidneys and intestines. These are rarely depicted on snuff bottles. Animals, on the other hand appear with regularity, the most common being the dragon.

A dragon is shown in the example at right on a porcelain bottle in splendid red and blue and clutching the inevitable fiery pearl. One of the traditions of Chinese art is that only the Emperor, his sons and princes of the first and second ranks were permitted to own an artefact illustrated with a dragon having five claws. Four-clawed dragons were restricted to princes of the third and fourth ranks, while the common folk had to be content with a dragon having three claws. However, it is common to find that many older bottles have dragons with five claws.

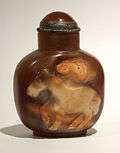

The horse is another animal frequently used in the decorative work. The horse is one of the Seven Treasures of Buddhism. Its symbolism points to speed, perseverance, rank, power and wealth. The symbolism of wealth and power came about because the horse carried those of importance. In the example at left, the horse seems to be carved in a very amateurish way, but in this school of bottle production, naïveté was the style.

The hare represents a wish for long life and even immortality. In Chinese tradition it is believed that if one attains a sufficiently high standard of morality and enlightenment, one will become one of the immortals.

Other commonly used symbols

The three legged toad is a mythical creature. It was thought to be an animated purse containing an inexhaustible supply of coins, hence it represents wealth and has become a symbol of the unattainable.

The fish is both an emblem of wealth and abundance and of harmony and connubial bliss. The fish emblem is used in a variety of decorative ways. Bamboo is a frequent motif. Because of its durability and its being evergreen it has come, along with many other symbols, to signify longevity.

"Inside painted" bottles

Inside painted are glass bottles which have pictures and often calligraphy painted on the inside surface of the glass.

Their scenes are an inch or two high and are painted while manipulating the brush through the neck of the bottle at times only a quarter inch across, in reverse. Ursula Bourne, in her treatise on snuff, suggested that artisans painted on their backs to make it easier to work through the narrow opening.[1] A skilled artist may complete a simple bottle in a week while something special may take a month or more and the best craftsmen will produce only a few bottles in a year.

Gan Xuanwen, also known as Gan Xuan has long been recognized as an important early artist of inside-painted snuff bottles in China. Quite a number of his bottles carry cyclical dates together with a reign period, and hence his works can be dated for certainty to roughly the first quarter of the 19th century, during the late Jiaqing (1796-1820) and early Daoguang (1821-1850) reigns of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911). [2]

It was not until the early 19th century and late in the Jiaqing reign that snuff bottles decorated with inside painting came to the fore. The inspiration of inside-painted snuff bottles might have originated from the court, but did not receive any support of the imperial workshops. Nevertheless, this kind of snuff bottles quickly became the subject of acquisition for a new group of patrons, comprising officials, nobles, scholars and businessmen. Eventually the craft gained immense momentum in the late Qing and the early Republic periods, i.e. from the late 19th to the early 20th centuries. In Beijing, there were three renowned and influential masters, namely Zhou Leyuan, Ma Shaoxuan and Ye Zhongsan. [2]Inside painted bottles are still made extensively for collectors and inexpensively as souvenirs.

Inside painted bottles themes include landscapes, bird-and-flowers, figures and auspicious themes. They are viewed as miniature paintings within the bottle.[2]

Snuff bullet

In recent years a popular method of snuff insufflation has been the snuff bullet. A simple snuff bullet consists of a small bottle with a plug in the base, a rotatable "dosing chamber" and a hole on the top. More advanced snuff bullets have variable dosing settings. They can be made of plastic, glass or metal.

Notes

- Ursula Bourne, Snuff, Shire Publications, 1990, p. 24.

- Hui, Humphrey K.F. (2002). Inkplay in Microcosm. p. 16. ISBN 962-7101-62-1.

Further reading

- The Collector's Book of Snuff Bottles by Bob C. Stevens

- Chinese Snuff Bottles: The Adventures and Studies of a Collector by Lilla S. Perry

- The Water, Pine and Stone Retreat Collection of Snuff Bottles

- Moss, Hugh M. (2008). A Treasury of Chinese Snuff Bottles: The Mary and George Bloch Collection Volume 6 Arts of the Fire. Herald International. ASIN B0085P23A2.

- Low, Denis S.K. (2007). Chinese Snuff Bottles: From the Sanctum of Enlightened Respect III. Laurence King Publishing. ISBN 978-981-05-7886-2.

- Chinese Snuff Bottles: Masterpieces in Miniature by Eric J. Hoffman

- Wolfmar Zacken: 97 Chinesische Snuff Bottles aus China. Edition Galerie Zacke 1985

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Snuff bottles. |

- Hugh Moss – Chinese Snuff Bottles – large gallery of designs and online reference material e-yaji.com

- International Chinese Snuff Bottle Society

- Collector's Book of Chinese Snuff Bottle: Introduction of All Kinds of Bottle

- CuiQiXuan - inside-painting snuff bottles

- Zhang Haihua Inner Painting Anthology

- Large collection of christmas crystal ball

- guyuexuan snuff bottle

- International Chinese Snuff Bottle Association