Shame

Shame is an unpleasant self-conscious emotion typically associated with a negative evaluation of the self; withdrawal motivations; and feelings of distress, exposure, mistrust, powerlessness, and worthlessness.

Definition

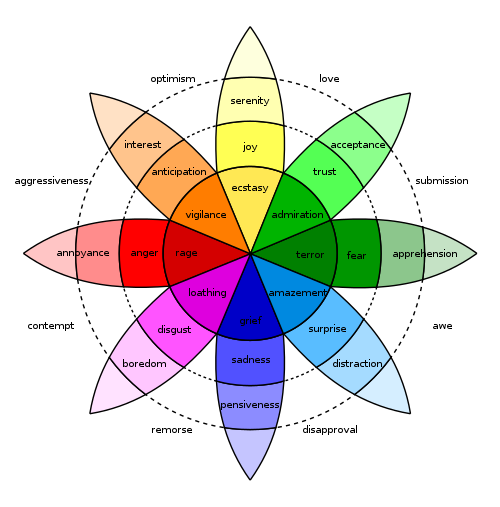

Shame is a discrete, basic emotion, described as a moral or social emotion that drives people to hide or deny their wrongdoings.[1] The focus of shame is on the self or the individual; it is the only emotion that is dysfunctional for the individual and functional at a group level. Shame can also be described as an unpleasant self-conscious emotion that involves negative evaluation of the self.[2] Shame can be a painful emotion that is seen as a "...comparison of the self's action with the self's standards..." but may equally stem from comparison of the self's state of being with the ideal social context's standard. Some scales measure shame to assess emotional states, whereas other shame scales are used to assess emotional traits or dispositions- shame proneness.[3] "To shame" generally means to actively assign or communicate a state of shame to another person. Behaviors designed to "uncover" or "expose" others are sometimes used to place shame on the other person. Whereas, having shame means to maintain a sense of restraint against offending others (as with modesty, humility, and deference). In contrast to having shame is to have no shame; behave without the restraint to offend others, similar to other emotions like pride or hubris.

Self-evaluation

When people feel shame, the focus of their evaluation is on the self or identity.[3] Shame is a self-punishing acknowledgment of something gone wrong.[4] It is associated with "mental undoing". Studies of shame showed that when ashamed people feel that their entire self is worthless, powerless, and small, they also feel exposed to an audience—real or imagined—that exists purely for the purpose of confirming that the self is worthless. Shame and the sense of self is stigmatized, or treated unfairly, like being overtly rejected by parents in favor of siblings' needs, and is assigned externally by others regardless of one's own experience or awareness. An individual who is in a state of shame will assign the shame internally from being a victim of the environment, and the same is assigned externally, or assigned by others regardless of one's own experience or awareness.

A "sense of shame" is the feeling known as guilt but "consciousness" or awareness of "shame as a state" or condition defines core/toxic shame (Lewis, 1971; Tangney, 1998). The key emotion in all forms of shame is contempt (Miller, 1984; Tomkins, 1967). Two realms in which shame is expressed are the consciousness of self as bad and self as inadequate.[5] People employ negative coping responses to counter deep rooted, associated sense of "shameworthiness".[6] The shame cognition may occur as a result of the experience of shame affect or, more generally, in any situation of embarrassment, dishonor, disgrace, inadequacy, humiliation, or chagrin.[7]

Shame, devaluation and their interrelationship are similar across cultures, prompting some researchers to suggest that there is a universal human psychology of cultural valuation and devaluation.[8]

Identification

Nineteenth-century scientist Charles Darwin described shame affect in the physical form of blushing, confusion of mind, downward cast eyes, slack posture, and lowered head; Darwin noted these observations of shame affect in human populations worldwide, as mentioned in his book "The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals". Darwin also mentions how the sense of warmth or heat, associated with the vasodilation of the face and skin, can result in an even more sense of shame. More commonly, the act of crying can be associated with shame.

Comparison with guilt

The boundaries between concepts of shame, guilt, and embarrassment are not easily delineated.[9] According to cultural anthropologist Ruth Benedict, shame arises from a violation of cultural or social values while guilt feelings arise from violations of one's internal values. Thus shame arises when one's 'defects' are exposed to others, and results from the negative evaluation (whether real or imagined) of others; guilt, on the other hand, comes from one's own negative evaluation of oneself, for instance, when one acts contrary to one's values or idea of one's self.[10] Thus, it might be possible to feel ashamed of thought or behavior that no one actually knows about [since one fears their discovery] and conversely, to feel guilty about actions that gain the approval of others.

Psychoanalyst Helen B. Lewis argued that, "The experience of shame is directly about the self, which is the focus of evaluation. In guilt, the self is not the central object of negative evaluation, but rather the thing done is the focus."[11] Similarly, Fossum and Mason say in their book Facing Shame that "While guilt is a painful feeling of regret and responsibility for one's actions, shame is a painful feeling about oneself as a person."[12]

Following this line of reasoning, Psychiatrist Judith Lewis Herman concludes that "Shame is an acutely self-conscious state in which the self is 'split,' imagining the self in the eyes of the other; by contrast, in guilt the self is unified."[13]

Clinical psychologist Gershen Kaufman's view of shame is derived from that of affect theory, namely that shame is one of a set of instinctual, short-duration physiological reactions to stimulation.[14][15] In this view, guilt is considered to be a learned behavior consisting essentially of self-directed blame or contempt, with shame occurring consequent to such behaviors making up a part of the overall experience of guilt. Here, self-blame and self-contempt mean the application, towards (a part of) one's self, of exactly the same dynamic that blaming of, and contempt for, others represents when it is applied interpersonally.

Kaufman saw that mechanisms such as blame or contempt may be used as a defending strategy against the experience of shame and that someone who has a pattern of applying them to himself may well attempt to defend against a shame experience by applying self-blame or self-contempt. This, however, can lead to an internalized, self-reinforcing sequence of shame events for which Kaufman coined the term "shame spiral".[14] Shame can also be used as a strategy when feeling guilt, in particular when there is the hope to avoid punishment by inspiring pity.[16]

One view of difference between shame and embarrassment says that shame does not necessarily involve public humiliation while embarrassment does; that is, one can feel shame for an act known only to oneself but in order to be embarrassed one's actions must be revealed to others. In the field of ethics (moral psychology, in particular), however, there is debate as to whether or not shame is a heteronomous emotion, i.e. whether or not shame does involve recognition on the part of the ashamed that they have been judged negatively by others.

Another view of the dividing line between shame and embarrassment holds that the difference is one of intensity.[17] In this view embarrassment is simply a less intense experience of shame. It is adaptive and functional. Extreme or toxic shame is a much more intense experience and one that is not functional. In fact on this view toxic shame can be debilitating. The dividing line then is between functional and dysfunctional shame. This includes the idea that shame has a function or benefit for the organism.[18]

Immanuel Kant and his followers held that shame is heteronomous (comes from others); Bernard Williams and others have argued that shame can be autonomous (comes from oneself).[19][20] Shame may carry the connotation of a response to something that is morally wrong whereas embarrassment is the response to something that is morally neutral but socially unacceptable. Another view of shame and guilt is that shame is a focus on self, while guilt is a focus on behavior. Simply put: A person who feels guilt is saying "I did something bad.", while someone who feels shame is saying "I am bad".

Comparison with embarrassment

Embarrassment has occasionally been viewed in the literature as a less severe or intense form of shame, but it is distinct from shame in that it involves a focus on the self-presented to an audience rather than the entire self, and that it is experienced as a sense of fluster and slight mortification resulting from a social awkwardness that leads to a loss of esteem in the eyes of others. We have characterized embarrassment as a sudden-onset sense of fluster and mortification that results when the self is evaluated negatively because one has committed, or anticipates committing, a gaffe or awkward performance before an audience. So, because shame is focused on the entire self, those who become embarrassed apologize for their mistake, and then begin to repair things and this repair involves redressing harm done to the presented self.[21] One view of difference between shame and embarrassment says that shame does not necessarily involve public humiliation while embarrassment does; that is, one can feel shame for an act known only to oneself but in order to be embarrassed one's actions must be revealed to others. Therefore shame can only be experienced in private and embarrassment can never be experienced in private.[21] In the field of ethics (moral psychology, in particular), however, there is debate as to whether or not shame is a heteronomous emotion, i.e. whether or not shame does involve recognition on the part of the ashamed that they have been judged negatively by others. This is a mature heteronomous type of shame where the agent does not judge herself negatively, but, due to the negative judgments of others, suspects that she may deserve negative judgment, and feel shame on this basis.[22] Therefore, shame may carry the connotation of a response to something that is morally wrong whereas embarrassment is the response to something that is morally neutral but socially unacceptable.

The Shame, Guilt and Anger Study

The manner in which children, adolescents, and adults manage and express their feelings of anger has caught the attention of June Price Tangney and her colleagues. They looked into previous studies that had been performed prior to the creation of their own report. While looking at studies done of college students, shame was not experienced alone. Anger arousal, suspiciousness, resentment, irritability, a tendency to blame others for negative events, and indirect expressions of hostility were all experienced with the emotion of shame. College students were more likely to report a desire to punish others, as well as a desire to hide, when rating personal shame versus guilt experiences and that is when these other emotions increase feelings of shame.[23] Tangney et al. found that shame is painful, exposing, disapproving, self-directed, and causes forms of defense towards others. These characteristics are extreme, but shame enters a new level when one's behavior becomes avoidant, retaliated, and blaming. In redirecting anger outside the self, shamed individuals may be attempting to regain a sense of agency and control which is so often impaired in the shame experience, so they looked at possibilities of how anger and shame go hand in hand. Once angered, people often feel ashamed of being angry, the experience of shame itself fosters feelings of other-directed anger and hostility, and the acute pain of shame can lead to a sense of ‘humiliated fury' directly toward the self and toward a real or imagined disapproving other. Negative affect fosters feelings of anger and the ‘instigation to aggress'. Thus, from this perspective it may be the pain of shame that accounts for its link with indexes of anger and hostility.[23] The study performed by Tangney et al. explored relation of shame proneness and guilt proneness to constructive versus destructive responses to anger among 302 children, 427 adolescents, 176 college students, 194 adults. During the study, it proved that shame proneness did relate to maladaptive anger. From the study, we found out that children were positively correlated with guilt and was not related to shame, but when looking at the older participants, the results were more varied than the children.

Participants: The study was done with children from an elementary school, a large university, and people traveling through a large urban airport where data took place on the weekends to avoid bias business travelers. Procedures: The participants all filled out the ARI and TOSCA questionnaires in many different small groups that were conducted on different days. Children, adolescents, and college students all followed the same procedures. For the non-college adults (airport travelers) sample, they completed the ARI and TOSCA as a single packet questionnaire in the airport waiting areas.

Results: The results on table 1, 2, and 3 showed that the relationship of shame and guilt to anger-related indexes for children, adolescents, college students, and adults. This showed shame was factored out from guilt and could also be shown in a vice versa manner. In the range of the study, it proved that shame and guilt proneness correlated highly positively. There were many factors that proved these correlations. Shame and guilt share a number of common features. When dealing with shame and guilt, they can also interact with respect in the same situation. In the study, (Tangney, Burggraf, & Wagner, 1995), we found that the effect of partialling out guilt from shame is negligible. Guilt represents how people are experiencing feeling guilty but without them feeling shame.

Table One: In the experiment, when looking at table 1 we are comparing the relation of shame and guilt to anger arousal. When we look at table one, shame was highly correlated to anger arousal. When looking at the proneness to guilt uncomplicated by shame, it showed a negative correlation with anger in children. When looking at the adolescents, college students, and adults, it showed as no relation. The numbers of the children and adolescents were very different, but not when compared to the college students and adults in the study. The variables below showed people's characteristic intentions when they are angry. In this study, the participants were asked to rate what they would feel like doing when they are angry, but not the action they would actually take when they are angry. The participants were given a reference to each scenario. Here, there was shown some shocking differences in correlation between shame and guilt. In this study shame was more positively correlated. The study showed that the correlations between guilt and constructive intentions became less pronounced with age, which was predicted.

Table Two: Table two shows that the shame-prone participants are more prone to anger than non-shame-prone participants but are also be more likely to have unconstructive actions with their anger. This goes for all ages which would be eights years old all the way to adulthood. It was clear that shame-prone individuals had to do with unconstructive responses to anger and are maladaptive. In the indexes of direct, physical, verbal and aggression that is aimed directly at the target(symbolic aggression), was true in aspect of proving that shame-proneness relates to maladaptive and unconstructed behavior. When measuring symbolic aggression, the scale measure the nonverbal reactions like slamming doors and shaking their fists. Symbolic aggression does not have any direct physical touch. The same pattern continued with Indirect Aggression scales which would be breaking something of value to that person and malediction which would be talking behind their back. When a person may be very angry at his or her spouse then goes home and takes it out on the spouse then that would be measured by the Displaced Aggression Scale, which this indeed also followed the same pattern. The Anger Held in scale concludes there is a {ruminative} kind of anger. Which would be obsessively and constantly thinking about the situation over and over in your head. Looking at the proneness to shame-free, guilt was negatively correlated with the indexes of aggression with all ages. Table two shows that holding anger in and ruminating on it was strongly correlated with shame and with all ages. There is one exception, Self-Aggression scale, which is being angry at oneself for the situation for example (I am mad at myself for trusting him/her in the first place). Self-Aggression was positively correlated with shame of all ages, but it was also moderately positively correlated with proneness to shame free guilt among college students and adults. In conclusion, besides Self Aggression, these indexes of aggressive responses to anger showed consistency with proneness to shame and proneness to guilt. People prone to feel shame about the entire self are much more likely to have an aggressive response in contrast to less shame-prone. When angered, people who are guilt prone are less likely to be aggressive.

Table Three: In table three the first cluster shows the Relations of Shame and Guilt to Direct Constructive Response to Anger. This is looking at the target of their anger is a non hostile way. In this experiment, across the four age groups "shame free" guilt was shown to correlate with anger management strategies. Shame was unrelated to the responses of anger. As with the same assumptions to constructive intentions, it was assumed guilt and adaptive response to anger would go up with age. But, in the study it showed the opposite that adults were actually lower than children. In the next cluster we look at Escapist-Diffusing responses. These were not clearly shown as adaptive or maladaptive. This study was done to attempt to diffuse anger. Examples of this would be, going on a run to distract you, hanging out with friends, etc. You want to be able to remove yourself from the situation by doing nothing. The findings from this experiment were very mixed. The experiment showed that shame was not related to the likelihood of developing these tendencies, which would show a positive correlation in shame between all of the age groups. This showed as people get older, they learn to react to anger and let the situation pass even though it might not be the best situation in the long run. The next cluster looks at Cognitive Reappraisals of Anger-Eliciting Situations. This means, once people are mad they often go back and rethink the persons roll in the situation. You go back and think wondering if you made the mistake or if the other person did or if it could have been prevented. The results showed that shame and anger are mixed in Cognitive Reappraisals or Anger-Eliciting Situations. Shame was unrelated to reappraisals, except it was found in college students. The last cluster of variables is the Projected Long-Term Consequences of Everyday Episodes of Anger. Participants were asked to think about an event and how they would respond to it and how long that their consequence would be. It was proved that the proneness to shame was generally inversely related to positive long term consequence. The results were highest in older participants. The people who were shame prone did not think about the consequences of their anger.[23]

Four subtypes

There are many different reasons that people might feel shame. According to Joseph Burgo, there are four different aspects of shame. He calls these aspects of shame paradigms. In his first subdivision of shame he looks into is unrequited love; which is when you love someone but your partner does not reciprocate, or one is rejected by somebody that they like; this can be mortifying and shaming. Unrequited love can be shown in other ways as well. For example, the way a mother treats her new born baby. An experiment was done where a mother showed her baby love and talked to the baby for a set period of time. She then went a few minutes without talking to the baby. This resulted with the baby making different expressions to get the mother's attention. When the mother stopped giving the baby attention, the baby felt shame. The second type of shame is unwanted exposure. This would take place if you were called out in front of a whole class for doing something wrong or if someone saw you doing something you didn't want them to see. This is what you would normally think of when you hear the word shame. Disappointed expectation would be your third type of shame according to Burgo. This could be not passing a class, having a friendship go wrong, or not getting a big promotion in a job that you thought you would get. The fourth and final type of shame according to Burgo is exclusion which also means being left out. Many people will do anything to just fit in or want to belong in today's society. This happens all the time at school, work, friendships, relationships, everywhere. People will do anything to prove that they belong. Shame causes a lot of stress on people daily, but it also teaches people a lot of lessons. Without having shame people would never be able to learn a lesson and never be able to grow from their mistakes.

Subtypes

- Genuine shame: is associated with genuine dishonor, disgrace, or condemnation.

- False shame: is associated with false condemnation as in the double bind form of false shaming; "he brought what we did to him upon himself". Author and TV personality John Bradshaw calls shame the "emotion that lets us know we are finite".[24]

- Secret shame: describes the idea of being ashamed to be ashamed, so causing ashamed people to keep their shame a secret.[25]

- Toxic shame: describes false, pathological shame, and Bradshaw states that toxic shame is induced, inside children, by all forms of child abuse. Incest and other forms of child sexual abuse can cause particularly severe toxic shame. Toxic shame often induces what is known as complex trauma in children who cannot cope with toxic shaming as it occurs and who dissociate the shame until it is possible to cope with.[26]

- Vicarious shame: refers to the experience of shame on behalf of another person. Individuals vary in their tendency to experience vicarious shame, which is related to neuroticism and to the tendency to experience personal shame. Extremely shame-prone people might even experience vicarious shame even to an increased degree, in other words: shame on behalf of another person who is already feeling shame on behalf of a third party (or possibly on behalf of the individual proper). The Dutch term for this feeling is 'plaatsvervangende schaamte', the German term is die Fremdscham and in the Spanish language it is referred to as vergüenza ajena.[27]

Shame Code

The Shame Code was developed to capture behavior as it unfolds in real time during the socially stressful and potentially shaming spontaneous speech task and was coded into the following categories: (1) Body Tension, (2) Facial Tension, (3) Stillness, (4) Fidgeting, (5) Nervous Positive Affect, (6) Hiding and Avoiding, (7) Verbal Flow and Uncertainty, and (8) Silence.[28]

Fidget Factor: hiding, fidgeting, nervous positive and low levels of stillness. Individuals high on Fidget displayed high levels of fidgeting and hiding behaviors, such as hiding their face and avoiding any eye contact with the experimenter, and low nervous positive affect or still-ness. By making repeated movements and avoiding direct contact with the experimenter, individuals who scored high on the Fidget factor communicated clearly and obviously that they were distressed while giving a speech. This non-verbal communication is a signal of discomfort to the observer and is perhaps an unconscious request for help." These behaviors that are included in the fidget factor lead youth to have difficulty forming relationships as these actions may be perceived as inauthentic or secretive. Fidgeting has been identified through discourse analysis of couples in conflict as a visual cue of shame, related to facial tension and masking of expressions.

Freeze Factor: stillness, facial tension and silence. Individuals who scored higher on this factor typically displayed a lack of any movement, facial tension such as lip biting and furrowing their brows, and a lack of any spoken words. Freezing is ultimately a withdrawal from a situation that one cannot escape physically, hence providing no action (in this case a speech) may reflect an effort to eliminate the possibility of negative evaluation. These behaviors that are included in the freeze factor "reflected participants" actual internalized shame, consistent with previous research. Freezing is a behavioral response to threat in mammals and it may be that those who scored higher on this factor were experiencing more intense shame during the speech. They convey a sense of helplessness that may initially elicit sympathetic or comforting actions.

Trait Shame: A negative evaluation implies flaws reflective of the self, rather than of a behavior.

State Shame: When depending on your current state, do you feel shame?

Shame proneness was associated with more fidgeting and less freezing, but both stillness and fidgeting are social cues that communicate distress to observers, and may elicit less harsh responses. Thus, both may be an attempt to diminish further shaming experiences. Shame involves global, self-focused negative attributions based on the anticipated, imagined, or real negative evaluations of others and is accompanied by a powerful urge to hide, withdraw, or escape from the source of these evaluations. These negative evaluations arise from transgressions of standards, rules, or goals and cause the individual to feel separate from the group for which these standards, rules, or goals exist, resulting in one of the most powerful, painful, and potentially destructive experiences known to humans.[28]

Shame and narcissism

It has been suggested that narcissism in adults is related to defenses against shame[29] and that narcissistic personality disorder is connected to shame as well.[30][31] According to psychiatrist Glen Gabbard, NPD can be broken down into two subtypes, a grandiose, arrogant, thick-skinned "oblivious" subtype and an easily hurt, oversensitive, ashamed "hypervigilant" subtype. The oblivious subtype presents for admiration, envy, and appreciation a grandiose self that is the antithesis of a weak internalized self which hides in shame, while the hypervigilant subtype neutralizes devaluation by seeing others as unjust abusers.[30]

Stigma

Stigma occurs when society labels someone as tainted, less desirable, or handicapped. This negative evaluation may be "felt" or "enacted". When felt, it refers to the shame associated with having a condition and the fear of being discriminated against... when enacted it refers to actual discrimination of this kind.[32] Shame in relation to stigma studies have most often come from the sense and mental consequences that young adolescents find themselves trapped in when they are deciding to use a condom in STD or HIV protection. The other use of stigma and shame is when someone has a disease, such as cancer, where people look to blame something for their feelings of shame and circumstance of sickness. Jessica M. Sales et al. researched young adolescents ages 15–21 on whether they had used protection in the 14 days prior to coming in for the study. The answers showed implications of shame and stigma, which received an accommodating score. The scores, prior history of STDs, demographics, and psychosocial variables were put into a hierarchical regression model to determine probability of an adolescents chances of using protected sex in the future. The study found that the higher sense of shame and stigma the higher chance the adolescent would use protection in the future. This means that if a person is more aware of consequences, is more in-tune with themselves and the stigma (stereotypes, disgrace, etc.), they will be more likely to protect themselves. The study shows that placing more shame and stigma in the mind of people can be more prone to protecting themselves from the consequences that follow the action of unprotected sex.[33]

HIV-related stigma from those who are born with HIV due to their maternal genetics have a proneness to shame and avoidant coping. David S. Bennett et al. studied the ages 12–24 of self-reported measures of potential risk factors and three domains of internalizing factors: depression, anxiety, and PTSD. The findings suggested that those who had more shame-proneness and more awareness of HIV-stigma had a greater amount of depressive and PTSD symptoms. This means that those who have high HIV-stigma and shame do not seek help from interventions. Rather, they avoid the situation that could cause them to find themselves in a predicament of other mental health issues. Older age was related to greater HIV-related stigma and the female gender was more related to stigma and internalizing symptoms (depression, anxiety, PTSD). Stigma was also associated with greater shame-proneness.[34]

Chapple et al. researched people with lung cancer in regards to the shame and stigma that comes from the disease. The stigma that accompanies lung cancer is most commonly caused by smoking. However, there are many ways to contract lung cancer, therefore those who did not receive lung cancer from smoking often feel shame; blaming themselves for something they did not do. The stigma effects their opinions of themselves, while shame is found to blame other cancer causing factors (tobacco products/anti-tobacco products) or ignoring the disease in avoidant coping altogether. The stigma associated with lung cancer effected relationships of patients with their family members, peers, and physicians who were attempting to provide comfort because the patients felt shame and victimized themselves.[32]

Social aspects

According to the anthropologist Ruth Benedict, cultures may be classified by their emphasis on the use of either shame (a shame society) or guilt to regulate the social activities of individuals.[35]

Shame may be used by those people who commit relational aggression and may occur in the workplace as a form of overt social control or aggression. Shaming is used in some societies as a type of punishment, shunning, or ostracism. In this sense, "the real purpose of shaming is not to punish crimes but to create the kind of people who don't commit them".[36]

Shame campaign

A shame campaign is a tactic in which particular individuals are singled out because of their behavior or suspected crimes, often by marking them publicly, such as Hester Prynne in Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter. In the Philippines, Alfredo Lim popularized such tactics during his term as mayor of Manila. On July 1, 1997, he began a controversial "spray paint shame campaign" in an effort to stop drug use. He and his team sprayed bright red paint on two hundred squatter houses whose residents had been charged, but not yet convicted, of selling prohibited substances. Officials of other municipalities followed suit. Former Senator Rene A. Saguisag condemned Lim's policy.[37] Communists in the 20th century used struggle sessions to handle corruption and other problems.[38]

Public humiliation, historically expressed by confinement in stocks and in other public punishments may occur in social media through viral phenomena.[39]

Research

Psychologists and other researchers who study shame use validated psychometric testing instruments to determine whether or how much a person feels shame. Some of these tools include the Guilt and Shame Proneness (GASP) Scale,[40] the Shame and Stigma Scale (SSS), the Experience of Shame Scale, and the Internalized Shame Scale. Some scales are specific to the person's situation, such as the Weight- and Body-Related Shame and Guilt scale (WEB-SG), the HIV Stigma Scale for people living with HIV and the Cataldo Lung Cancer Stigma Scale (CLCSS) for people with lung cancer.[41] Others are more general, such as the Emotional Reactions and Thoughts Scale, which deals with anxiety, depression, and guilt as well as shame.

See also

- Badge of shame

- Cognitive dissonance

- Guilt (emotion)

- Haya (Islam)

- Lady Macbeth effect

- Measures of guilt and shame

- Online shaming

- Psychological projection

- Reintegrative shaming

- Scopophobia

- So You've Been Publicly Shamed, a 2015 book by journalist Jon Ronson about online shaming

Further reading

- Bradshaw, J. (1988) Healing the Shame That Binds You, HCI. ISBN 0-932194-86-9

- Gilbert, P. (2002) Body Shame: Conceptualisation, Research and Treatment. Brunner-Routledge. ISBN 1-58391-166-9

- Gilbert, P. (1998) Shame: Interpersonal Behavior, Psychopathology and Culture. ISBN 0-19-511480-9

- Goldberg, Carl (1991) Understanding Shame, Jason Aaronson, Inc., Northvale, NJ. ISBN 0-87668-541-6

- Hutchinson, Phil (2008) Shame and Philosophy. London: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 0-230-54271-9

- Lamb, R. E. (1983) Guilt, Shame, and Morality, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, Vol. XLIII, No. 3, March 1983.

- Lewis, Michael (1992) Shame: The Exposed Self. NY: The Free Press. ISBN 0-02-918881-4

- Middelton-Moz, J. (1990) Shame and Guilt: Masters of Disguise, HCI, ISBN 1-55874-072-4

- Miller, Susan B. (1996) Shame in Context, Routledge, ISBN 0-88163-209-0

- Morrison, Andrew P. (1996) The Culture of Shame. Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-37484-3

- Morrison, Andrew P. (1989) Shame: The Underside of Narcissism. The Analytic Press. ISBN 0-88163-082-9

- Nathanson, D., ed. (1987) The Many Faces of Shame. NY: The Guilford Press. ISBN 0-89862-705-2

- Schneider, Carl D. (1977) Shame, Exposure, and Privacy. Boston: Beacon Press, ISBN 0-8070-1121-5

- Uebel, Michael (2012). "Psychoanalysis and the Question of Violence: From Masochism to Shame". American Imago. 69 (4): 473–505. doi:10.1353/aim.2012.0022.

- Uebel, Michael (2016). "Dirty Rotten Shame? The Value and Ethical Functions of Shame". Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 59 (2): 1–20. doi:10.1177/0022167816631398.

- Vallelonga, Damian S. (1997) An empirical phenomenological investigation of being ashamed. In Valle, R. Phenomenological Inquiry in Psychology: Existential and Transpersonal Dimensions. New York: Plenum Press, 123-155.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shame. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Shame |

| Look up shame in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Brene Brown Listening to Shame, TED Talk, March 2012

- Sample chapter from Phil Hutchinson's book Shame and Philosophy

- Understanding Shame and Humiliation in Torture

- US Forces Make Iraqis Strip and Walk Naked in Public

- Shame

- Humiliation is Simply Wrong (USA Today Editorial/Opinion)

- Hiding from Humanity: Disgust, Shame, and the Law

- Shame and Psychotherapy

- Shame and Group Psychotherapy

- Sexual Guilt and Shame

- Social usage of shame in historical times

References

- Shein, L. (2018). The Evolution of Shame and Guilt. PLoSONE, 13(7), 1-11.

- Parsa, S. (2018). Psychological Construction of Shame in Disordered Eating. New Psychology Bulletin, 15(1), 11-19.

- Schalkwijk, F., Stams, G. J., Dekker, J., & Elison, J. (2016). Measuring Shame Regulations: Validation of the Compass of Shame Scale. Social Behavior and Personality, 44(11), 1775-1791.

- Niedenthal, P. M., Krauth-Gruber, S. & Ric, F. (2017). Psychology of Emotion: Self-Conscious Emotions. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Jeff Greenberg; Sander L. Koole; Tom Pyszczynski (2013). Handbook of Experimental Existential Psychology. Guilford Publications. p. 159. ISBN 978-1-4625-1479-3.

- Edward Teyber; Faith Teyber (2010). Interpersonal Process in Therapy: An Integrative Model. Cengage Learning. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-495-60420-4.

- Broucek, Francis (1991), Shame and the Self, Guilford Press, New York, p. 5, ISBN 978-0-89862-444-1

- Sznycer, Daniel, Dimitris Xygalatas, Elizabeth Agey, Sarah Alami, Xiao-Fen An, Kristina I. Ananyeva, Quentin D. Atkinson et al. "Cross-cultural invariances in the architecture of shame." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115, no. 39 (2018): 9702-9707.

- Tangney, JP; Miller Flicker Barlow (1996), "Are shame, guilt, and embarrassment distinct emotions?", Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70 (6): 1256–69, doi:10.1037/0022-3514.70.6.1256, PMID 8667166

- "Cultural Models of Shame and Guilt" Archived April 18, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Lewis, Helen B. (1971), Shame and guilt in neurosis, International University Press, New York, ISBN 978-0-8236-8307-9, PMID 5150685

- Fossum, Merle A.; Mason, Marilyn J. (1986), Facing Shame: Families in Recovery, W.W. Norton, p. 5, ISBN 978-0-393-30581-4

- Herman, Judith Lewis (2007), "Shattered Shame States and their Repair" (PDF), The John Bowlby Memorial Lecture, archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2010

- Kaufman, Gershen (1992), Shame: The Power of Caring (3rd ed.), Schenkman Books, Rochester, VT, ISBN 978-0-87047-052-3

- Nathanson, Donald (1992), Shame and Pride: Affect, Sex, and the Birth of the Self, W.W. Norton, NY, ISBN 978-0-393-03097-6

- Shame and the Origins of Self-esteem: A Jungian Approach. Psychology Press. 1996. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-415-10580-4.

- Graham, Michael C. (2014). Facts of Life: ten issues of contentment. Outskirts Press. pp. 75–78. ISBN 978-1-4787-2259-5.

- Graham, Michael C. (2014). Facts of Life: ten issues of contentment. Outskirts Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-4787-2259-5.

- Williams, Bernard: Shame and Necessity

- Hutchinson, Phil: chapter four of Shame and Philosophy

- Niedenthal, P. M., Krauth-Gruber, S. & Ric, F. (2017). Psychology of Emotion: Self-conscious Emotions. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Turnbull, D. J. (2012). Shame: In Defense of an Essential Moral Emotion. PhD thesis, Birkbeck, University of London.

- Tangney, J.P., Wagner, P. E., Hill-Barlow, D., Marschall, D. E., & Gramzow, R. (1996). Relation of Shame and Guilt to Constructive Versus Destructive Responses to anger Across the Lifespan. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(4), 797-809.

- Bradshaw, John (December 1996), Bradshaw on the Family: A New Way of Creating Solid Self-Esteem, HCI, ISBN 978-1-55874-427-1

- Gilligan, James (1997) Violence: Reflections on a National Epidemic Vintage Books, New York

- Bradshaw, John (2005) Healing the Shame That Binds You (2nd edition) Health Communications, Deerfield Beach, Florida, page 101 Archived August 28, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 0-7573-0323-4

- Paulus, F.M., Müller-Pinzler, L., Jansen, A., Gazzola, V. and Krach, S., 2014. Mentalizing and the role of the posterior superior temporal sulcus in sharing others' embarrassment. Cerebral cortex, 25(8), pp.2065-2075.

- De France, K., Lanteigne, D., Glozman, J. & Hollenstain, T. (2017). A New Measure of the Expression of Shame: The Shame Code. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 26(3), 769-780.

- Wurmser L, Shame, the veiled companion of narcissism, in The Many Faces of Shame, edited by Nathanson DL. New York, Guilford, 1987, pp. 64–92.

- Gabbard GO, subtypes of narcissistic personality disorder. Bull Menninger Clin 1989; 53:527–532.

- Young, Klosko, Weishaar: Schema Therapy – A Practitioner's Guide, 2003, p. 375.

- Chapple, A., Ziebland, S. & McPherson, A. (2004). Stigma, Shame, and blame experienced by patients with lung cancer: qualitative study. British Medical Journal, 328(7454), 1470-1473.

- Sales, J. M., DiClemente, R. J., Rose, E. S., Wingood, G. M., Klein, J. D. & Woods, E. R. (2007). Relationship of STD-Related Shame and Stigma to Female Adolescents' Condom-Protected Intercourse. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40, 573.

- Bennett, D. S., Hersh, J., Herres, J. & Foster, J. (2016). HIV-Related Stigma, Shame, and Avoidant Coping: Risk Factors for Internalizing Symptoms Among Youth Living with HIV? Child Psychology & Human Development, 47(4), 657-664.

- Stephen Pattison, Shame:Theory, Therapy and Theology. Cambridge University Press. 2000. 54. ISBN 0521560454

- Roger Scruton, BRING BACK STIGMA, in Modern Sex: Liberation and its Discontents, Chicago 2001, p. 186.

- Pulta, Benjamin B. "Spray campaign debate heats up." Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Sun.Star Manila. June 26, 2003.

- Hayoun, Massoud (2012-03-21). "Photos: Fathers of Chinese Leaders at Revolutionary 'Struggle Sessions'". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2019-02-02.

- Jon Ronson (March 31, 2015). So You've Been Publicly Shamed (hardcover)

|format=requires|url=(help). Riverhead Books. ISBN 978-1594487132. - Cohen TR; Wolf ST; Panter AT; Insko CA (May 2011). "Introducing the GASP scale: a new measure of guilt and shame proneness". J Pers Soc Psychol. 100 (5): 947–66. doi:10.1037/a0022641. PMID 21517196.

- Cataldo JK; Slaughter R; Jahan TM; Pongquan VL; Hwang WJ (January 2011). "Measuring stigma in people with lung cancer: psychometric testing of the cataldo lung cancer stigma scale". Oncol Nurs Forum. 38 (1): E46–54. doi:10.1188/11.ONF.E46-E54. PMC 3182474. PMID 21186151.