Richard Henderson (jurist)

Richard Henderson (April 20, 1735–January 30, 1785) was an American pioneer and merchant who attempted to create a colony called Transylvania just as the American Revolutionary War was starting. After the Declaration of Independence (1776) and the organization of the state government in North Carolina, he was re-elected judge, but was prevented from accepting that position by his participation in a scheme organized under the name of the Transylvania Compact.[1]

Early life

Henderson was born in Hanover County, Virginia Colony on April 20, 1735. His parents were Samuel Henderson and Elizabeth Williams Henderson. He had a brother, Thomas Henderson. In 1762, he moved to Granville County, North Carolina, studied law, was admitted to the bar, practiced law, and in 1769 was appointed judge of the Inferior Court.[1]

Viewed as a member of the gentry, he had been a target of Regulator violence.[2] He was a member of a Church of England parish in Williamsboro during this time.[2]

In the company of wilderness explorers

In 1772, surveyors placed the land officially within the domain of the Cherokee tribe, who required negotiation of a lease with the settlers. Tragedy struck as the lease was being celebrated when a Cherokee warrior was murdered by a white man. James Robertson's skillful diplomacy made peace with the irate Native Americans, who threatened to expel the settlers by force if necessary.[3]

In 1775, a treaty was held between the Cherokee and a delegation of the Transylvania Company, headed by Richard Henderson. Under the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals (or the Treaty of Watauga) at present-day Elizabethton, Tennessee, the Transylvania Company purchased a vast amount of land from the Cherokees, including most of present-day Kentucky and part of Tennessee.[3]

The treaty was technically illegal since the purchase of land from Native Americans was reserved by the government in the Proclamation of 1763 (the British, the governments of Virginia and North Carolina, and, later, the United States, all forbade private purchase of land from Indians).

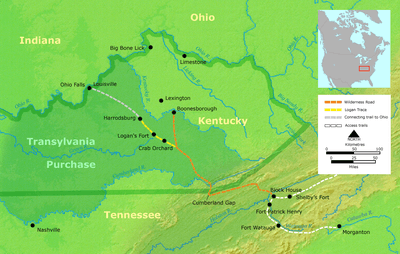

During the treaty, Dragging Canoe, son of the Cherokee chief Attacullaculla, made a speech condemning the sale of Cherokee land and broke from the general Cherokee tribal government to form the sub-tribe known as the Chickamauga. After Henderson's Transylvania Company had bought Kentucky (although other tribes claimed it, such as the Shawnee), Daniel Boone was hired to widen the Indian path over Cumberland Gap to facilitate migration. This road became known as the Wilderness Road.[3]

The Transylvania Purchase at Sycamore Shoals

In 1775, Henderson gathered chiefs of the Cherokee Indians and negotiated the Treaty of Watauga at Sycamore Shoals at present day Elizabethton, Tennessee, during which time he purchased all the land lying between the Cumberland River, the Cumberland Mountains, and the Kentucky River, and situated south of the Ohio River.[3]

The land thus delineated encompassed an area half as large as the present state of Kentucky. In order to facilitate settlement, Henderson hired Daniel Boone, who had hunted extensively in Kentucky, to blaze the Wilderness Road through the Cumberland Gap and into the Transylvania land purchase. Henderson also purchased the land known as the Path Grant that allowed access to the Transylvania lands. That purchase is described on the Path Grant Deed.

To appease other prominent early explorers, Henderson held out other rewards. He offered Joseph Martin, founder of Martin's Station on Martin's Creek in present-day Rose Hill, Lee County, Virginia, a spot as an agent and entry taker for the company, in charge of keeping tabs on settlers moving westward; Henderson offered Martin's brother Bryce a tract of 500 acres (2.0 km2) adjacent to the Cumberland Gap.[4]

The Transylvania Compact

Henderson followed Boone to a site that came to be called Boonesborough, located on the southern bank of the Kentucky River, Henderson encouraged the few settlers there to hold a constitutional convention.

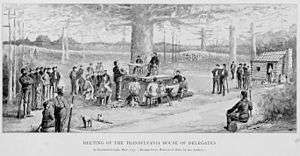

In May 1775, under the shade of a huge elm tree, a compact organizing a frame of government was drafted. The intended government entailed executive, legislative, and judicial branches. After concluding the Transylvania Compact, Henderson returned to North Carolina and on behalf of his fellow investors in the land scheme petitioned Congress seeking to make Transylvania America’s fourteenth colony. Despite those efforts, Congress was unwilling to act without the consent of Virginia and North Carolina, both of whom claimed jurisdiction over the region in question.

In June 1776 the Virginia General Assembly prohibited the Transylvania Land Company from making demands on settlers in the region and in December 1778 declared the Transylvania claim void.[5]

Henderson and his partners instead received a grant of 12 square miles (31 km²), on the Ohio River below the mouth of Green River.

Revolutionary period

In 1779, Judge Henderson was appointed one of six commissioners to run the line between Virginia and North Carolina into Powell's valley. He settled in North Carolina, where he practiced farming on a large scale. He served as a captain (1779-1781) in the Granville County Regiment of the Hillsborough District Brigade in the North Carolina militia in the Revolutionary War.[6]

He represented Granville County, North Carolina in the House of Commons of the North Carolina General Assembly in 1781. He was elected by the legislatures to be one of the Councilors of State in 1772 and 1788.[7][8]

One of his sons, Leonard Henderson, was a Chief Justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court (1829–1833). Henderson, North Carolina was named for him. The other son, Archibald Henderson, was a legislature representing Rowan County, North Carolina.[7][8]

Death

He died at the age of 49 on January 30, 1785. He was buried on his farm near Williamsboro, North Carolina on Nutbush Creek. His wife was Elizabeth Keeling, the daughter of an English peer, Lord Keeling. Their children were Fanny (b. 1764), Richard (b. 1766), Archibald (b. 1768), Elizabeth (b. 1770), Leonard (b. 1778), and John (b. 1780).

Legacy

Henderson County, Illinois was named for Richard Henderson as was Henderson County, Kentucky[9] and its seat Henderson, Kentucky.

Ashland was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973.[10][11]

References

- Miller, Mark F. (1988). "Richard Henderson". NCPedia. Retrieved September 13, 2019.

- Bishir, Catherine (2005). North Carolina Architecture. UNC Press. p. 56.

- Henderson, Archibald (1920). The Conquest of the Old Southwest. pp. 212–236.

- Boone: A Biography, Robert Morgan, Algonquin Books, Chapel Hill, 2008 ISBN 978-1-56512-615-2

- Christian G. Fritz, American Sovereigns: The People and America's Constitutional Tradition Before the Civil War (Cambridge University Press, 2008) at p. 55-60 ISBN 978-0-521-88188-3

- Lewis, J.D. "Richard Henderson". The American Revolution in North Carolina. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- Connor, R.D.D. (1913). A Manual of North Carolina (PDF). Raleigh: North Carolina Historical Commission. p. 453-. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- Wheeler, John H. (1874). "The Legislative Manual and Political Register of the State of North Carolina". Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- The Register of the Kentucky State Historical Society, Volume 1. Kentucky State Historical Society. 1903. p. 35.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- Survey and Planning Unit Staff (September 1972). "Ashland" (pdf). National Register of Historic Places - Nomination and Inventory. North Carolina State Historic Preservation Office. Retrieved 2014-08-01.

- Allen, William B. (1872). A History of Kentucky: Embracing Gleanings, Reminiscences, Antiquities, Natural Curiosities, Statistics, and Biographical Sketches of Pioneers, Soldiers, Jurists, Lawyers, Statesmen, Divines, Mechanics, Farmers, Merchants, and Other Leading Men, of All Occupations and Pursuits. Bradley & Gilbert. pp. 53–54. Retrieved 2008-11-10.