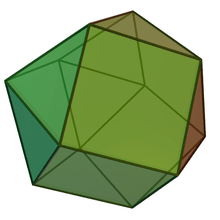

Triangular orthobicupola

In geometry, the triangular orthobicupola is one of the Johnson solids (J27). As the name suggests, it can be constructed by attaching two triangular cupolas (J3) along their bases. It has an equal number of squares and triangles at each vertex; however, it is not vertex-transitive. It is also called an anticuboctahedron, twisted cuboctahedron or disheptahedron. It is also a canonical polyhedron.

| Triangular orthobicupola | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Johnson J26 - J27 - J28 |

| Faces | 2+6 triangles 6 squares |

| Edges | 24 |

| Vertices | 12 |

| Vertex configuration | 6(32.42) 6(3.4.3.4) |

| Symmetry group | D3h |

| Dual polyhedron | Trapezo-rhombic dodecahedron |

| Properties | convex |

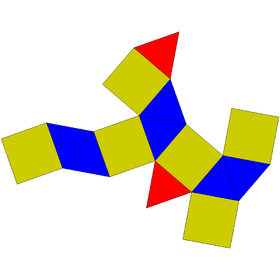

| Net | |

| |

A Johnson solid is one of 92 strictly convex polyhedra that is composed of regular polygon faces but are not uniform polyhedra (that is, they are not Platonic solids, Archimedean solids, prisms, or antiprisms). They were named by Norman Johnson, who first listed these polyhedra in 1966.[1]

The triangular orthobicupola is the first in an infinite set of orthobicupolae.

Relation to cuboctahedra

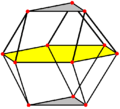

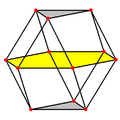

| Triangular orthobicupola | Triangular gyrobicupola |

|---|---|

|

|

| Both the triangular orthobicupola and the cuboctahedron (triangular gyrobicupola) contain a central regular hexagon. They can be dissected on this hexagon into pairs of triangular cupolae. | |

The triangular orthobicupola has a superficial resemblance to the cuboctahedron, which would be known as the triangular gyrobicupola in the nomenclature of Johnson solids — the difference is that the two triangular cupolas which make up the triangular orthobicupola are joined so that pairs of matching sides abut (hence, "ortho"); the cuboctahedron is joined so that triangles abut squares and vice versa. Given a triangular orthobicupola, a 60-degree rotation of one cupola before the joining yields a cuboctahedron. Hence, another name for the triangular orthobicupola is the anticuboctahedron.

The elongated triangular orthobicupola (J35), which is constructed by elongating this solid, has a (different) special relationship with the rhombicuboctahedron.

The dual of the triangular orthobicupola is the trapezo-rhombic dodecahedron. It has 6 rhombic and 6 trapezoidal faces, and is similar to the rhombic dodecahedron.

Formulae

The following formulae for volume, surface area, and circumradius can be used if all faces are regular, with edge length a:[2]

The circumradius of a triangular orthobicupola is the same as the edge length (C=a).

Related polyhedra and honeycombs

The rectified cubic honeycomb can be dissected and rebuilt as a space-filling lattice of triangular orthobicupolae and square pyramids.[3]

References

- Johnson, Norman W. (1966), "Convex polyhedra with regular faces", Canadian Journal of Mathematics, 18: 169–200, doi:10.4153/cjm-1966-021-8, MR 0185507, Zbl 0132.14603.

- Stephen Wolfram, "Triangular orthobicupola" from Wolfram Alpha. Retrieved July 23, 2010.

- http://woodenpolyhedra.web.fc2.com/J27.html