New-York Central College

New-York Central College, commonly called New-York Central College, McGrawville, and simply Central College, was an abolitionist[1] institution of higher learning founded by Cyrus Pitt Grosvenor and other anti-slavery Baptists in McGraw, New York (at the time called McGrawville; not modern McGrawville, New York).[2] The sponsoring organization was the American Baptist Free Mission Society, of which Grosvenor was a vice-president.[3] It was chartered by New York State in April 1848 and opened in September of that year.[4]:326

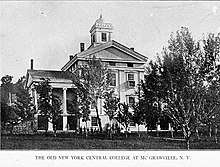

Main building, 1850. The first two floors held classrooms and the third a dormitory for male students. | |

Other name | Central College, McGrawville |

|---|---|

| Active | 1848–1860 |

| Founder | Cyrus Pitt Grosvenor |

Religious affiliation | Baptist |

| Students | 100–200 |

| Location | McGraw (at the time called McGrawville), Cortland County , New York , 13101 , United States 42.5961°N 76.0931°W |

The college lasted about 10 years. As put by the author of a modern study, "A little town tried to create a place without any prejudice, and it did make a difference. It created humanitarians and heroes in a time where nothing else existed like this."[5] While Oberlin and Oneida had accepted African-American students, and Oberlin female students, New-York Central College was the first institution in the country founded to accept all students, and did so from its very first day. This was the vision of its founder, Cyrus Pitt Grosvenor.[2]

As was common in the Antebellum period, when there were no public secondary schools anywhere in America, Central had a large preparatory, or high school, division.

College experience

This is how the college was described by an alumna and instructor, Angeline Stickney:

[T]he world will frown upon me, because I am a student of this unpopular institution, and I expect to get the name that I have heard applied to all who come here, "fanatic". I am glad that I am here because I love this institution. I love the spirit that welcomes all to its halls, those of every tongue, and of every hue, which admits of "no rights exclusive", which holds out the cup of knowledge in its crystal brightness for all to quaff; and if this is fanaticism, I will glory in the name "fanatic." Let me live, let me die a fanatic. I will not seal up in my heart the fountain of love that gushes forth for all the human race. And I am glad I am here because there are none here to say, "thus far thou mayst ascend the hill of Science and no farther," when I have just learned how sweet are the fruits of knowledge, and when I can see them hanging in such rich clusters, far up the heights, looking so bright and golden, as if they were inviting me to partake. And all the while I can see my brother gathering those golden fruits, and I mark how his eye brightens.... No, there are none here to whisper, "that is beyond thy sphere, thou couldst never scale those dizzy heights"; but, on the contrary, here are kind voices cheering me onward.[6]:48

College curriculum and faculty

Grosvenor "proposed a 'free institution,' for the 'literary, scientific, moral, and physical education of both sexes and of all classes of youth.'" The school's curriculum included classical education as well as agricultural science. The Rev. Grosvenor served as the school's first President, 1849–1850.[2] Replacing Grosvenor as President was Leonard G. Calkins, "a finished scholar, an accomplished orator, and a true gentleman, a deep thinker, of active temperament".[4]:327 In a newspaper advertisement we find that the Manual Labor Department was "under the supervision of Luther Wellington, a Practical Farmer, a kind and benevolent man, on a farm of 187 acres (76 ha)." Under the "careful training" of the President students took a Rhetorical Class "with daily exercises in Extemporaneous Speaking", "not to be overlooked in this day of 'public speaking'".[7]

The college was modeled after Oberlin, which in 1835 began admitting blacks and in 1837 women. However, New-York Central College was the first American college founded specifically to educate all students: black and white, male and female. It was also the first to have African-American professors, in a position filled by three men: first Charles L. Reason, who was an alumnus, then his replacement William G. Allen, a graduate of the Oneida Institute, another short-lived school which was a predecessor of the college. After Allen's departure (see below) he was replaced by George Boyer Vashon, the first African-American graduate of Oberlin. Reason was the first black college professor in the country. Allen was Professor of Rhetoric and Greek; in 1850, when he was appointed, he was "well known as a lecturer upon the origin, literature, and destiny of the African race."[8]

Shortly after its opening, the College and McGraw were hit by a smallpox outbreak. Four students died and the College had to cloase briefly. For a brand-new institution, this was a major blow.

In 1850 the students of the college published resolutions they had passed in support of William L. Chaplin, in jail for helping two slaves escape.[9] Also in 1850, the college and town were afflicted by smallpox, and 6 students died. At that time, there were 150 students.[3]:8

In 1851 it was one of 11 colleges to receive New York State legislative funding; it received $1,500 (equivalent to $46,098 in 2019), the same amount as New York University, Fordham University, Hamilton College, and Madison University (Colgate).[10] A few weeks later, another report says that the college received an appropriation of $25,000 (equivalent to $768,300 in 2019).[11] A Baptist report of 1851 states that its Free Mission Society raised $30,000 (equivalent to $921,960 in 2019) for the college.[12]

Students and professors were not allowed to use alcohol or (much more unusual) tobacco.[13]

Samuel J. May in 1851 spoke at the college on the English abolitionist George Thompson (abolitionist).[14]

In 1852, according to Professor William G. Allen, "There is now a project on foot to attach a medical department to New York Central College. — A glorious idea this, as, if it should be successful, it will afford an opening for study to the very many colored young men who are now, by prejudice and scorn, shut out of most, if not all, of the medical colleges in the land. The faculty are physicians of Syracuse, in high standing and repute."[15] Nothing came of this, although there is a reference to a Professor of Anatomy at the college.[16] The medical college was established in New York City.

In 1852, the faculty were:

- Wm. Tillinghast, A.M., professor of mathematics

- William G. Allen, professor of Greek and German Languages, rhetoric and belles lettres (literature). After the departure of Grosvenor, who taught Hebrew, Allen was listed as teaching it.

- E.R. Akin, A. M., D. M., professor of natural sciences

- A. B. Campbell, A. M, professor of Latin language aud Literature

- G. L. Brockett, A. B., tutor

- A. J. Chamberlain, teacher of French and drawing[17]

The college's first commencement was in 1855, with 5 graduates.[18] In 1856 there were 226 students and 9 faculty,[19] and approximately 50% were African-American. Most were in the college's preparatory (high school) program.

Hostility to the college

Because of its equalitarian treatment of blacks, the "nigger college at McGrawville", as it was called,[19] received a lot of public vituperation.

A New York legislator said that rather than giving a state appropriation to that "vile sink of pollution", it would be better given to "a mob that will raze it to the ground", because it "was at war with every principle of American liberty".[20] The New-York Tribune called it a "treasonable college", an "obnoxious edifice" where, "if things are suffered to go on at this rate, this whole region will become infected with Abolitionism; the contagion of Free Speech will spread til the Fugitive Slave law will become a nullity and the Union will collapse!"[21]

The local hostility to the college was a factor in its demise. As it was put in a typically inaccurate newspaper column, which mistakenly puts Mary King's father at the head of the college:

There is a pretentious wooden structure, of a semi-classic exterior, standing in the little village of McGrawville, Cortland County, N.Y., which was formerly the seat of what was known, in the anti-slavery days, as the "New York Central College." This institution was devoted to the education of negroes.... The head of this college...was a clergyman of liberal views, who became a stout advocate of intermarriage between whites and negroes: a development, by the way. which is regarded in the South to this day with holy horror, and militated against by severe penalties. But there were no statutes against miscegenation in New York in those days, so that a burly, ambitious negro, heartily in accord with the matrimonial views of the august parent, proceeded to elope one day with his daughter. This unexpected denouement quickly illustrated in a very prosaic way the disparity between theory and practice. Seizing his gun, and taking Immediate transportation in the most available vehicle, the irate parent pursued the bi-colored couple with all the impetuosity of Pharoah chasing the flying Israelites down into the Red Sea. And then the "New York Central College" for the education of negro youths experienced the sad fate of Pharoah at the hiatus of the purple waters.[22]

William Allen affair

A scandal arose when African-American professor William G. Allen became engaged to a white student, Mary King. To escape violent repercussions, Allen fled to New York City, where he was joined by his fiancée. They married—the first black male–white female marriage in the country's history—and immediately left for England, never to return. This event exacerbated already lingering social and political opposition to the school. (Marlene Parks has published a collection of press clippings, which show the hostility.[23])

Closure

The school was later denied funding by the New York State Legislature, and it was bankrupt by 1858.[24]:14

President Callins left for a position at "an eminent law school in Albany". "Everything that an able faculty could do to advance the interests of the Institution has been done, and yet the College has not prospered. Its friends are discouraged, and the Board of Directors disheartened. Present appearances indicate that the College will either pass into the hands of its colored friends, or be purchased by the citizens of M'Grawville, and be renovated and reorganised into a seminary or academic institution, or finally cease to exist as a College."[4]:327

Facing bankruptcy, the school was put into the hands of the wealthy activist Gerrit Smith, who lived nearby, in Peterboro. A smallpox epidemic struck McGrawville in 1860. The effects of the outbreak, coupled with the lingering social and political opposition and financial difficulties, caused the college to close that same year. Another source says it closed in 1859.[2]

The New York Central Railroad, with which there is no known connection, began in 1853.

New York Central Academy

According to the New York State Department of Education, New York Central Academy operated from 1864 to 1867.[25]:92 It owned and occupied the college property..[26] In 1868 it became a high school.[25]:55

Daniel S. Lamont, Secretary of War under President Grover Cleveland, was from McGraw, and studied as a child at the Central Academy, "the successor of a queer institution, known as the New York Central College, established by Gerrit Smith and other abolitionists, for the education of boys and girls without regard to color."[27] Lamont was born in 1851.

Alumni

- Charles L. Reason, first African American to teach college in the United States (at Central College)

- Angeline Stickney, American suffragist, abolitionist, and mathematician. Graduated in 1855 with the first class. During her last year she also taught; among her students was her eventual husband, astronomer Asaph Hall. Stickney, the largest crater on Mars's moon Phobos, is named for her.

- Asaph Hall, astronomer, known for his discovery of the moons of Mars.

- Maria Edmonia Lewis, sculptor

- Mahommah Gardo Baquaqua, former slave, missionary

- Eldridge Eugene Fish, scientist and school principal.[28]

- Herman Ossian Armour, co-founder of Armour & Co..

- A. J. Warner, school principal. attorney, member of Congress from Ohio,[29] President of the American Bimetallic League.[30]

- George B. Davis, Esq., attorney, Ithaca, New York (not George Breckenrith Davis)[31]

- Emma Grosvenor (ca. 1832–1853), daughter of founder Cyrus Grosvenor, died aged 21

- Sarah Grosvenor, her sister, married a Baptist minister and died at 92.

- John Quincy Cowee (1830–1921), Kansan farmer, described as "a scholar and a gentleman", with "an enviable reputation for truth and sobriety".[32]

- Judson Smith, D.D. (1837–1906), Congregational minister, professor at Oberlin, missionary[33][34][35]

See also

- Anton Wilhelm Amo (c. 1703 – c. 1759), a black man from Ghana who studied in Germany, became a philosopher, and taught in German universities.

- Juan Latino, a black college professor in sixteenth-century Spain

References

- Brawley, Benjamin (1976). Early Negro American writers : selections with biographical and critical introductions. Originally published by the University of North Carolina Press in 1935. Freeport, New York: Books for Libraries Press. p. 13. ISBN 0836902467.

- "Cyrus Pitt Grosvenor". Morning Star. October 1, 1995. p. 7. Archived from the original on November 19, 2010. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

- American Baptist Free Mission Society (1851). Anti-slavery missions : review of the operations of the American Baptist Free Mission Society, for the past year. Bristol, New York. p. 3.

- Goodwin, H.C. (1859). Pioneer history; or, Cortland County and the border wars of New York, from the earliest period to the present time. New York: A. B. Burdick.

- Creenan, Robert (October 2, 2017). "New York Central College the topic of McGraw author's new book". Cortland Standard.

- Hall, Angelo (1908). An Astronomer's Wife: The Biography of Angeline Hall. Baltimore: Nunn & Company. Archived from the original on 2016-07-30. Retrieved 2020-05-15.

- "New York Central College". The Liberator. March 24, 1854. p. 3. Archived from the original on July 25, 2019. Retrieved July 25, 2019 – via newspapers.com.

- "By Telegraph". Newport Daily News (Newport, Rhode Island). December 16, 1850. p. 2. Archived from the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved July 3, 2019 – via newspapers.com.

- "Resolutions of Central College". The Liberator. October 11, 1850. p. 1 – via newspapers.com.

- "New York Legislature". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. June 18, 1851. p. 3 – via newspapers.com.

- "Hunker Eloquence". The Liberator. 15 August 1851. p. 4 – via newspapers.com.

- "(Untitled)". Buffalo Daily Republic. 2 September 1851. p. 2 – via newspapers.com.

- "(Untitled)". The Advocate (Buffalo, New York). July 24, 1851. p. 3 – via newspapers.com.

- "George Thompson, M. P." The Anti-Slavery Bugle (Lisbon, Ohio). For the continuation click here. August 16, 1851. pp. 1–2 – via newspapers.com.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Allen, Wm. G. (May 20, 1852). "[Letter to the editor, May 6, 1852]". Frederick Douglass' Paper (Rochester, New York) – via accessiblearchives.com.

- Ten lectures on medical electricity. Auburn, New York. 1862. p. 14.

- "New York Central College". Buffalo Daily Republic. 6 May 1853. p. 2 – via newspapers.com.

- "College Commencements. New York Central College". New-York Tribune. 6 Aug 1855. p. 3 – via newspapers.com.

- Place, Frank, Personal recollections, archived from the original on December 25, 2018, retrieved December 24, 2018

- "Literature in the Legislature". Evening Post (New York, N.Y.). June 28, 1851. p. 2 – via newspapers.com.

- "Central College Anniversary". New-York Tribune. July 29, 1856. p. 6 – via newspapers.com.

- Benham, George A. (19 March 1899). "One woman's influence". Los Angeles Times. p. 41 – via newspapers.com.

- Parks, Marlene K. (2017). New York Central College, 1849-1860, McGrawville, N.Y. : the first college in the U.S. to employ black professors. McGraw Historical Society, through CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 9781517478124.

- Elbert, Sarah, ed. (2002). "Introduction". The American prejudice against color : William G. Allen, Mary King, and Louisa May Alcott. Boston: Northeastern University Press. ISBN 9781555535452.

- Miller, George Frederick (1922). The academy system of the State of New York. Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University.

- New York Constitutional Convention, 1867–68. New York Convention Manual. State of New York. p. 220.

- "Col. Daniel Lamont". South Bend Tribune (South Bend, Indiana). March 14, 1893. p. 6. Archived from the original on July 25, 2019. Retrieved July 25, 2019 – via newspapers.com.

- "Eldridge Eugene Fish". Buffalo Courier. 18 Mar 1894. p. 9 – via newspapers.com.

- "A. J. Warner". Concordia Empire (Concordia, Kansas). October 1, 1885. p. 2 – via newspapers.com.

- "General Warner". Salt Lake Tribune. May 25, 1895. p. 8 – via newspapers.com.

- "Noted civil and criminal lawyer". Star-Gazette (Elmira, New York). 15 April 1899. p. 2 – via newspapers.com.

- "Death of J. Q. Cowee". Enterprise-Chronicle (Burlingame, Kansas). 22 September 1921. p. 1 – via newspapers.com.

- "Judson Smith, O.T.S." Oberlin Alumni Magazine. Vol. 3 no. 1. October 1906. p. 53.

- Tenney, Henry M. (November 1906). "Judson Smith, D.D." Oberlin Alumni Magazine. Vol. 3 no. 2. pp. 57–60.

- "Judson Smith dead". Birmingham News (Birmingham, Alabama). 30 June 1906. p. 5 – via newspapers.com.

Further reading

- Parks, Marlene K. (2018). New York Central College, Volume 3. Condensed Version of Volumes 1 and 2. McGraw Historical Society. ISBN 9781729614884.

- McAdam, Todd R. (January 16, 2017). "McGraw producers to screen film on interracial college to DC". Cortland Standard.

- Parks, Marlene K. (2017). New York Central College, 1849–1860, McGrawville, N.Y. : Volume 1. Part 1. Newspaper Articles concerning the College, November 1847—December, 1849. Part 2. Alphabetical Biographical Sketches Abbott—Lyons. Part 3. Newspaper Articles concerning the College, March, 1850—December, 1850. McGraw Historical Society. ISBN 9781517478124.

- Parks, Marlene K. (2017). New York Central College, 1849–1860, McGrawville, N.Y. : Volume 2. Part 1. Newspaper Articles concerning the College, January, 1851—December, 1853. Part 2. Alphabetical Biographical Sketches Lyons—Young. Part 3. Newspaper Articles concerning the College, March, 1854—August, 1861. McGraw Historical Society. ISBN 9781548505752.

- Wright, Albert Hazen (1960). Pre-Cornell and Early Cornell VIII. Cornell's Three Precursors. I. New York Central College. Cornell University.

Video

- Kimberly, Carl; Kimberly, Mary (2018). New York Central College: An Experiment in Education in McGrawville 1848-1860. Cortland County Historical Society.