Murzyn

Murzyn (Polish pronunciation: [muʐɨn]) was historically a common Polish word for a black person. According to University of Warsaw language professor Dr hab. Marek Łaziński, the word had little negative association through the 1980s and into the 1990s; but as the Polish language evolved the word became less and less common and it's associations became more and more pejorative. The word roughly translates in English to either of the nouns Black or Negro.[1]

Etymology

The word 'Murzyn' is derived by borrowing the German word Mohr,[2] derived from Latin Maurus,[3] similarly to the English word 'moor'.[4]

Meaning and usage

In the Polish language, 'Murzyn' means somebody with black skin (a proper noun, uppercase spelling).[5] The lowercase word ('murzyn', a common noun) has several metaphoric and informal meanings.

Murzyn (feminine form: Murzynka, diminutive: Murzynek) can be translated into English as "black man". The standard nominative plural is Murzyni, which is using the "personal masculine" suffix, while the impersonal suffix (that is: Murzyny) is pejorative.[6][7]

However, the word "Murzyn" is often confused with the English word "Negro", without familiarising oneself with the fact that the socio-cultural roots of both words are significantly different. Comparing Polish "Murzyn" to English "Negro" without taking into account the word's neutral origins and non-racist historical background has caused the majority of the controversy over the word in recent years. In the opinion of Dr Marek Łaziński, it has also been associated with Shakespeare's 'noble' Othello, usually called a "moor" in English.[8] According to Łaziński the word Murzyn in Polish is sometimes perceived as offensive, though many Poles would defend its use. In comparison, a direct translation of the English word "black", "czarny", does not seem better to him since it often carries negative connotations in Polish, though he feels it may eventually replace Murzyn due to the influence of foreign languages on Polish. Łaziński, writing in the language advice column of the Polish dictionary, suggests that in cases where an individual may perceive Murzyn to be offensive, geographic or national designations should be used.[9] According to Marcin Miłkowski, writing in 2012, the word "previously considered neutral, is now all but banned in newspapers".[10]

According to philologist Grażyna Zarzycka, the word "'Murzyn', which in the opinion of many Poles, including academics, is not offensive, is seen by some black people as discriminatory and derogatory."[11] For Antonina Kloskowska, meanwhile, writing in "Race", ethnicity and nation: international perspectives on social conflict, the word Murzyn "does not carry pejorative connotations.[4] Moreover, the term "black", favoured in the English-speaking countries, which is translated into Polish as "czarny" (literally meaning "black"), is also seen as non-offensive, as this word describes a color (just like the Spanish "negro" literally meaning "black color").

Poland's first black Member of Parliament, John Godson, said in 2011 that the word was not offensive and that he was proud to be called a Murzyn[12].He also said he saw no problem in using the terms "Murzyn", "ciemnoskóry" ["dark-skin"], "Afrykańczyk" ["African man"], or "Afropolak" ["Afro-Pole"]. [13] Later however, in 2020, he tweeted "The word has evolved. If the people in question do not wish to be called "murzyn" - please do not call them that". [14]. Mamadou Diouf, a black Polish musician and representative of the Committee for the African Community (Komitet Społeczności Afrykańskiej), criticised Godson for his use of the word.[15]

James Omolo in his 2018 book Strangers at the Gate. Black Poland argues that regardless the neutrality of the term "Murzyn", in the perception of Poles it is associated with inferiority.[16] Among of other usage examples he cites a 2014 scandal with foreign minister Radoslaw Sikorski who reportedly said that Polish mentality suffers from "Murzyńskość" ["Murzynness"] adding "The problem in Poland is that we have very shallow pride and low self-esteem".[17] A black Polish MP, Killion Munyama, used the expression sto lat za Murzynami ["100 years behind the Murzyns"] while speaking to Godson about the status of LGBT issues in Poland, characterising it as behind the times.[18]

Professor Marek Łaziński has published the following opinion about the usage of the word, at the website of the Polish Language Council (though it is stressed that this is not yet the official position of the Council):

"I emphasize that the word Murzyn was once neutral, or at least the best possible, neutral and positive contexts of this noun can be found without difficulty, and people who used it in the eighties or nineties have no reason to feel guilty. However, words change associations and overtones in the course of natural changes in social consciousness. Today, the word Murzyn is not only burdened with bad associations, it is archaic.

There are several reasons for the gradual pejorativization of the noun Murzyn in Polish. Firstly, in all the languages of the Western world (including Polish), the basic names of black people during the era of slavery gave way to newer names. These changes first occurred in English and French (the languages of the societies most involved in the slave trade), later the languages with the greatest numbers of black people, and then after in other languages, albeit at different rates and degrees.

Secondly, the word " Murzyn" in Polish has acquired an exceptionally strong offensive phraseology. Of course, the harmful phraseology also applies to other human groups or nations, but the stereotyping of black people is unique in Polish and incomparable to the situation in neighbouring languages. Phraseology also strengthens the Murzyn-slave association. There is no guarantee that a change of designation will stop the harmful phraseology, but it will certainly make you wonder.

Thirdly (in relation to the first and the second): black and dark Poles, mostly from Africa in the first or second generation, and the vast majority of black Americans living in Poland temporarily treat this word as offensive. This is partly due to automatic comparison with others and languages (the word Murzyn was translated for a long time without commentary as Negro or nègre in Polish-English and Polish-French dictionaries), and partly by constant experience of stereotyping due to skin colour, and often racism. It is worth respecting the sensitivity of the audience. Our neighbours with black skin prefer to be named on the basis of a specific nationality (e.g. Senegalese , Nigerian), prefer to be African, black, dark-skinned or simply black (although only a few decades ago, the connotations of the adjective black in relation to a black man were worse than the noun Murzyn). The submission of an Afropolak modelled on an African-American is not typical for the Polish language.

Fourth and most important for a linguist: in many contexts the word Murzyn has been used unnecessarily. It is determined not by nationality or geographical origin, but by skin colour, and this feature, like hair colour, height, and type of figure, does not have to be important in describing a person . The word Murzyn in the subject of the sentence replaces the basic word man (Murzynka replaces the word woman), it forces us to indicate a physical feature that could remain unnamed if it were an adjective. It is easier to say simply a man instead of a black man than to replace the word."

In language

A saying sometimes used in Poland, Murzyn zrobił swoje, Murzyn może odejść, is actually a quote from the 1783 play Fiesco by German writer Friedrich Schiller (translated from the German as "The Moor has done his duty, the Moor can go"). The meaning of this phrase is: "once you've served your purpose, you're no longer needed".[20]

The lowercase word ('murzyn', a common noun) may mean:

- (informally) Somebody anonymously doing work for somebody else;

- (informally) Somebody with a dark brown tan;

- (informally) A hard working person forced to do hard labour.[21]

The English word "ghostwriter" can be translated informally in Polish as literacki Murzyn, in this case a "literary Negro".[22][23]

A murzynek in informal Polish can also mean a popular type of chocolate cake, or a portion of strong coffee.[24]

A murzyn polski ("Polish murzyn") is a variety of black-billed pigeon.[25]

A murzynka is also a type of strawberry with small, dark red fruit.[26]

A murzyn is also another term for szołdra, a Silesian easter bread.

In Polish culture

A famous children's poem "Murzynek Bambo" has been criticized for imprinting a stereotypical image of an African child.[27] Others argue that the poem should be seen in the context of its time, and that commentators should not go overboard in analysing it.[28] A journalist Adam Kowalczyk says that he "did not become a racist" because of reading the poem.[29]

In 2014 a brand of Polish margarine, "Palma", which portrays a cartoony black person (first launched in 1972) was rebranded into "Palma z Murzynkiem", and the usage of this term attracted similar criticism. The use of the word "Murzynek" (a diminutive of Murzyn) was criticized by Polish-Senegalese Mamadou Diouf, who called for a boycott. Polish linguist Jerzy Bralczyk noted that the word "Murzyn" is not pejorative, but diminutives could be seen as such, if only because they are diminutives. The margarine producer, Bielmar, denied any racist views, and stated that the logo has been a distinctive part of the product for decades, abolishing it would result in a loss of the company's strongest brand, and the current rebranding with the diminutive (from "Palma" to "Palma z Murzynkiem") is simply a response to the common nickname of the product as used by the customers.[30]

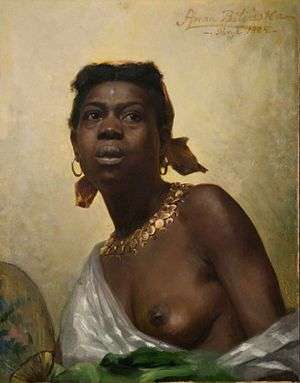

Pod Murzynami ("Under the Murzyns") is also a not uncommon name for chemist's shops or tenement buildings in Poland. Often an image of a black person accompanies the name.[31]

A Polish general of African descent, Władysław Franciszek Jabłonowski (1769–1802), was nicknamed "Murzynek".[32]

References

- "Murzyn | definition in the Polish-English Dictionary - Cambridge Dictionary". dictionary.cambridge.org. Retrieved 2020-08-13.

- Aleksander Brückner, Słownik etymologiczny języka polskiego, Wiedza Powszechna, Warsaw, 1993, ISBN 83-214-0410-3, p.348.

- "Mohr, Duden online

- Antonina Kłoskowska (1 July 1996). "Nation, race and ethnicity in Poland". In Peter Ratcliffe (ed.). "Race", ethnicity and nation: international perspectives on social conflict. Psychology Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-1-85728-661-8. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "Murzyn". Słownik języka polskiego (in Polish). PWN.

- Edited by Margaret H. Mills (1999). Slavic gender linguistics. p. 210. ISBN 9027250758. Retrieved 2013-04-23.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Katamba, Francis (2004). Morphology: Morphology: Primes, phenomena and processes. ISBN 9780415270809.

- "Czy Obama jest Murzynem?". Juraszek.net.

- "Lista odpowiedzi" (in Polish). poradnia.pwn.pl.

- Marcin Miłkowski (2012). "The Polish language in the digital age". p. 47. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - Grażyna Zarzycka, "Dyskurs prasowy o cudzoziemcach na podstawie tekstów o Łódzkiej Wieży Babel i osobach czarnoskórych", Łódź, 2006, p. 143

- "Czy Murzynek Bambo to rasistowski wierszyk?" (in Polish). Tvp.pl. Archived from the original on 2012-01-05.

- ""Można mówić Murzyn, czarnoskóry albo Afropolak"", tnv24, November 12, 2011

- John Abraham Godson [@johngodson] (21 June 2020). "[...] Podobnie jest do słowa Murzyn. Ewoluował. Skoro zainteresowani nie chcą być nazwani murzynami - proszę ich tak nie nazywać" [It's similar with the word "Murzyn". It has evolved. If the people in question do not wish to be called "murzyn" - please do not call them that.] (Tweet) (in Polish) – via Twitter.

- "Murzyn to niewolnik. Szkoda, że poseł tego nie łapie" (in Polish). Tvn24.pl. Archived from the original on 2011-12-01. Retrieved 2011-11-30. Diouf: "Myślę, że pan poseł nie zna pochodzenia słowa, o którym mowa" - "I think, that the MP doesn't know the etymology of the word".

- James Omolo, Strangers at the Gate. Black Poland, p. 69, at Google Books, 2018, ISBN 8394711804

- "Report: Poland's Foreign Minister Blasts 'Worthless' U.S. Relationship", Time Magazine, June 22, 2014

- "Munyama do Godsona: "Jesteśmy sto lat za Murzynami". "Newsweek" o kulisach dyskusji PO" (in Polish). gazeta.pl. 25 February 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- "„Murzyn" i „Murzynka"". rjp.pan.pl. Retrieved 2020-08-13.

- "Murzyn zrobił swoje, Murzyn może odejść - definition in Megasłownik - the online dictionary".

- "Murzyn". Słownik języka polskiego (in Polish). PWN.

- "Jak Colin wyłowił Alicję" (in Polish). Tvn24.pl.

- "PANDORA W KONGU" (in Polish). wydawnictwoliterackie.pl.

- Murzynek, PWN

- Murzyn polski, PWN

- "Murzynka". sjp.pwn.pl.

- "Czy "Murzynek Bambo" obraża Afrykanów?"

- Murzynek Bambo dla licealistów? Archived 2012-03-27 at the Wayback Machine, Colemi.pl (in Polish)

- Huckleberry Finn a Murzynek Bambo, Debata.olsztyn.pl (in Polish)

- http://wiadomosci.gazeta.pl/wiadomosci/1,114871,15684470,Kultowa_margaryna_z_Murzynkiem_oburza_Afrykanczykow.html

- "Murzynek Bambo w Afryce mieszka, czyli jak polska kultura stworzyła swojego Murzyna" (in Polish). historiasztuki.uni.wroc.pl.

- "Jabłonowski Władysław Franciszek" (in Polish). encyklopedia.pwn.pl.

External links

| Look up murzyn in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |