Michael O'Flanagan

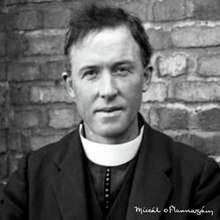

Michael O'Flanagan (Irish: An tAthair Mícheál Ó Flannagáin; 13 August 1876 – 7 August 1942) was a Roman Catholic priest, Irish language scholar, inventor and historian. He was a popular, socialist Irish republican; "a vice-president of the Irish Agricultural Organisation Society, he was a proponent of land redistribution."[1] He was Gaelic League envoy to the United States from 1910 to 1912, and he supported the striking dockers in Sligo in 1913.[2]

Michael O'Flanagan | |

|---|---|

| |

| President of Sinn Féin | |

| In office 1933–1935 | |

| Preceded by | Brian O'Higgins |

| Succeeded by | Cathal Ó Murchadha |

| Chaplain of the First Dáil | |

| In office 1919–1921 | |

| Vice President of the Gaelic League | |

| In office 1920–1921 | |

| Vice President of Sinn Féin | |

| In office 1917–1923 | |

| In office 1930–1931 | |

| Personal details | |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Political party | Sinn Féin |

| Signature | |

| Website | frmichaeloflanagan |

| Nickname(s) | The Sinn Féin Priest |

O'Flanagan was friends with many of the leaders of the 1916 Easter Rising and was vocal in his admiration for the sacrifice made by the men of Easter Week.[3] He was active in reorganising the Sinn Féin party after the Rising. He was the main driving force behind the Election of the Snows in North Roscommon in February 1917, when Count Plunkett won a by-election as an independent candidate.[4]

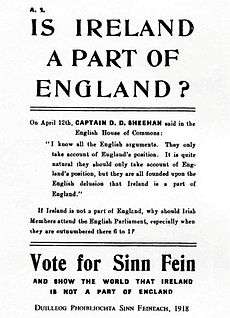

At the Sinn Féin Convention in October 1917, Éamon de Valera was elected President. Along with Arthur Griffith, O'Flanagan was elected joint Vice-President, a position he held from 1917 to 1923 and again from 1930 to 1931. He campaigned for the imprisoned Griffith in the East Cavan by-election in 1918, and was instrumental in securing the seat. For this O'Flanagan was suspended by the Bishop; he went on to work full-time for Sinn Féin and was the main platform speaker and campaigner during the 1918 election.[5]

While O'Flanagan was Acting President of Sinn Féin in 1920, he corresponded publicly with David Lloyd George about peace moves, to the upset of his colleagues. He went on to hold meetings with Lloyd George and Edward Carson in January 1921, and reported British terms to Éamon de Valera on his return. He was President of Sinn Féin from 1933 to 1935.

O'Flanagan travelled extensively throughout his lifetime, spending many years in the United States, and several months in Rome. After five months as Republican Envoy to Australia he was deported in 1923. O'Flanagan, James Larkin and Frank Ryan were considered the best open-air orators of the twentieth century.[6]

He was suspended from the priesthood for many years because of his political beliefs and attitudes. In later years he edited the 1837 Ordnance Survey letters and prepared sets for institutions and universities; in the 1930s he worked on a series of County Histories, and ten volumes were published by the time of his death. He died in 1942, was given a State Funeral, and is buried in the Republican Plot in Glasnevin Cemetery.[7]

Early life and education

Michael Flanagan was born on 13 August 1876 at Cloonfower in the parish of Kilkeeven, close to Castlerea in County Roscommon. He was the fourth of eight children born to Edward Flanagan (born 1842) and Mary Crawley (born 1847). Both of Michael's parents were fluent speakers in both Irish and English, living on a small farm in what was known as a breac or speckled gaeltacht.[3] When he was three years old, "An Gorta Beag, the famine of 1879" swept through the west of Ireland.[8]

In both 1845 and 1879 the poorest in society, as they faced starvation, were forced to bear the brunt of the recession as Landlords, supported by the British State, refused to stop food exports or reduce rent. Indeed many landlords tried to use both crises to evict tenants into destitution and starvation in order to replace them with more profitable ranches while continuing to export food abroad.[9]

While conditions were not as severe as thirty years earlier, there was great fear among the people who had survived the earlier starvation, expressed in a wave of religious fervour, as for example, the apparitions at Knock in 1879.[10] The Flanagan family were staunch supporters of the Fenian movement.[11] As a young man Michael lived through the evictions, boycotts and shootings of the Land War. His parents were and members of the Land League, and he was fascinated by politics, avidly following the rise and fall of Charles Stewart Parnell.[12]

O'Flanagan attended the local national school at Cloonboniffe, known as the Don School,[13] where his teacher "was a Michael O'Callaghan, and he became O'Flanagan's mentor and friend; O'Callaghan would also be a prominent Gaelic League activist."[1] In 1890 O'Flanagan went on to attend secondary school at Summerhill College in Sligo. He entered St Patrick's College, Maynooth in the autumn of 1894 where he had an excellent academic record, winning prizes in theology, scripture, canon law, Irish language, education, and natural science.[6]

O'Flanagan was ordained a priest of the Third Order of St. Francis for the Diocese of Elphin in Sligo Cathedral on 15 August 1900 at the age of 24.[6] It was around this time that he began to use the Irish form of his surname.

"O'Flanagan was appointed to the academic staff of Summerhill College as professor of Irish; he immediately set about a study of the sounds of Irish and in 1904 published a small book[14] on the rules of aspiration and eclipses. It was also he who proposed the wearing of the fainne as a sign to others of readiness to speak Irish."[1]

While working in Sligo O'Flanagan was active in his promotion of the Irish culture and language, and he gave evening language classes in Sligo Town Hall. He was a founding member and secretary of the Sligo Feis, which was first held in 1903, when Padraig Pearse was invited to give a lecture titled "The Saving of a Nation" in Sligo Town Hall. Both Pearse and Douglas Hyde were the judges of the Irish language competitions in 1903 and again in 1904.[6]

Fundraising in the United States

O'Flanagan was a keen supporter rural development and Irish self-reliance, with practical knowledge and point of view, having grown up on a small farm. He was a skilled public speaker and communicator and was vocal in agitating for radical social and political change. In 1904 he was invited by his Bishop John Joseph Clancy and Horace Plunkett to travel to the United States on a speaking and fundraising tour.[11] Douglas Hyde wrote to him on 3 November to say that he had read O'Flanagan's work on Irish Phonetics with great interest and that he was sorry to see him go to America.[15]

His mission was to promote Irish industry, in particular the lace industry, and to find investment and collect donations for agricultural and industrial projects in the west of Ireland. The diocese of Elphin had purchased the Dillon estate at Loughglynn in County Roscommon and had established a dairy industry there, managed by nuns of the Franciscan Missionaries of Mary. Part of O'Flanagan's mission was to pay off the outstanding debt on the venture.[6]

O'Flanagan was an imaginative and innovative fundraiser; for example he brought a sod clay from every county, which was arranged as a map of Ireland on his travels, and charged people a dollar to step on the soil of their native county.[3] He travelled with a small group of lace workers, who would give public demonstrations and show samples of various regional styles of Irish lace. O'Flanagan was an excellent publicist, and placed notices in regional newspapers to advertise the roadshow. He gave countless interviews and lectures on his travels and made many connections with the Irish American community.[12]

He remained in the United States until he was recalled to Ireland in 1910.[6]

Gaelic League Envoy

In June 1910 O'Flanagan returned to Ireland. He joined Sinn Féin, the party with which his name would become synonymous, and was elected to the standing committee.[5] The party, founded by Arthur Griffith in 1905, was then in its "Monarchist" phase; O'Flanagan's radical influence would help transform the party in 1917.[3]

In August, after attending a meeting of the Gaelic League he was elected to the standing committee. He reported "the existence in every part of the States of an Irish population that is ever anxious to hear of home progress and to meet any representatives of any Irish movement." Within a few weeks of his appointment to the standing committee the Gaelic League asked him to return to United States on another fundraising mission.[6]

Along with Fionan McColum he travelled back to America to commence another round of fundraising. He went with the blessing of Bishop Clancy, who published a letter congratulating O'Flanagan on his selection. This mission was "moderately successful" remitting £3,054 between March 1911 and July 1912.[6] He returned to Ireland where Bishop Clancy appointed him curate in Roscommon in 1912. On 19 October Bishop Clancy died, and his successor, Dr. Bernard Coyne was a conservative who resented O'Flanagan's perceived modernism and independence.

In 1912 O'Flanagan was invited to Rome to give a series of lectures for Advent, and was a guest preacher in San Silvestro for four weeks. While in Rome he spent time with his good friend Dr. John Hagan who was director of the Irish College, and there is a large collection of letters between the two in the Hagan archive there. O'Flanagan is often referred to as "Brosna'" in the letters.[16]

In March 1913 a protracted strike broke out at the Sligo Docks. In May O'Flanagan visited the strikers to show his solidarity and advised them to continue insisting for their rights.[12] It has been suggested that this display of socialism prompted the Bishop to move O'Flanagan to Cliffoney.[12] When the advanced nationalist Keating Branch took control of the Gaelic League, O'Flanagan was elected to the Standing Committee for two years.[11] A recently discovered photograph shows O'Flanagan in a large group, many of whom were advanced nationalists at a meeting of the Gaelic League outside Galway Town Hall in August 1913.[17]

O'Flanagan was active in attempting to reorganise and popularise the Sinn Féin party. On 22 February 1914 while staying in Crossna, he wrote a letter to Count Plunkett with suggestions for the spread of Sinn Féin:

I enclose my rough outline of plan of organisation. It will need a good deal of criticism in regard to detail. My object was to get money in as quickly as possible so that we might get on with the work to hand. You would need somebody who has made a study of organisation methods to consider it carefully before adoption.

I think myself that the Sinn Féin organisation will now spread through the country if vigorously pressed from headquarters. Get the Sinn Féin Executive to send out copies of the rules to the principal men amongst the local committees of North Roscommon. If Sinn Féin spreads rapidly the Irish Alliance will not be needed. However, there is no time to lose.[18]

In 1914 O'Flanagan was invited back to Rome to give a series of Lenten lectures, and he spent six weeks, again preaching in San Silvestro's.[6] At the end of his course of lectures he received a medal from the pope, Benedict XV. While preparing to leave Rome, O'Flanagan was informed he was to be removed from Roscommon and was to proceed to Cliffoney in County Sligo.[19]

Cliffoney

In late July 1914 the Bishop Bernard Coyne transferred O'Flanagan to Cliffoney, a small village in the parish of Ahamlish in north county Sligo. He had instructions from the bishop to assist the ailing priest, help the faltering lace industry in Cliffoney, and to look for land or a building for a village hall. Initially he rented a Lodge in Mullaghmore before eventually moving up to Cliffoney where he rented a cottage from Mrs. Hannan.[19]

While living in Cliffoney he actively campaigned against recruitment in the British army. His sermons were noted down by the RIC from the barracks next to the church who often occupied the front pew with notebooks to hand.[19]

Now, the local police were stationed across the road from the church, and the sergeant and five men attended Mass regularly, occupying first row of seats. The sergeant, whose name was Perry, called on Father Michael to lay off the agitating or he would have to take action. Father Michael responded on the next Sunday by calling on the police to resign. Sergeant Perry took out his notebook and took down everything....[20]

Along with his old student from Summerhill, Alec McCabe, O'Flanagan was active in organising a company of the Irish Volunteers in the Cliffoney area.[2] "At that time we had a Catholic Curate, the late Father Michael O'Flanagan, a great Irishman and strong supporter of the Republican Movement. He gave us every assistance and encouragement and advised the young men of the parish to join the Irish Volunteers. In all, forty men joined the Cliffoney Company."[21]

O'Flanagan condemned the export of food from the area, and demanded a fair and proper distribution of turbary rights. In newspaper pieces he contrasted Irish opinion-makers' outrage against Germany's contemporary treatment of Belgium with their indifference to England's ongoing treatment of Ireland.[22]

The Cloonerco Bog Fight

While living in Cliffoney O'Flanagan discovered that the villagers were being denied access to the local bogs by the Congested Districts Board, the public body in charge of land redistribution. After a protracted and fruitless correspondence with the CDB he eventually took action, coincidently on the day O'Donovan Rossa died in New York.[23]

On the feast of Saints Peter and Paul, 29 June 1915, a holiday of obligation, the congregation at the 12.30 pm mass were requested by O’Flanagan to remain after mass. He wished to say somethng about the local turfbanks.

An evidence of the ubiquitous role of the RIC is that a Sergeant Perry also remained behind to note in detail what O'Flanagan had to say. It was very direct, very simple: people were sick of promises and of the injunctions of MPs to keep quiet in the hope that when the war was over home rule would be given.[6]

On Wednesday 30 June 1915 O'Flanagan led some 200 his parishioners up to Cloonerco bog where they commenced cutting turf, an incident which became known as "The Cloonerco Bog Fight".[24] When the RIC constables, who had followed the marchers to the bog intervened, and threatened to arrest anyone who cut turf, O'Flanagan stepped forward and began cutting.[3] A large quantity of turf was harvested and distributed, despite an injunction being served on six of the turf-cutters and police interference.

Again we had a public meeting at the Cliffoney crossroads. One of the corners was occupied by the Police Barracks. At the beginning of the meeting none of the police were present. Before commencing to speak, I sent a messenger to the barracks asking the sergeant and his men to come out and witness what I had to say. When they made their appearance, I asked them in the presence of the people, to take down my exact words, so that they might be able to quote me correctly this time.[19]

The surplus turf was stacked outside the Fr. O'Flanagan Hall and opposite the R.I.C barracks. The stack was draped with a tricolour and a banner inscribed by O'Flanagan, saying Ár Moin Féin, "Our Own Turf" was attached, and attracted much attention from passers-by. The affair simmered on over the summer of 1915; eventually the locals in Cliffoney were granted access to the bogs.[24]

The Father O'Flanagan Hall

The villagers of Cliffoney had no church hall or communal gathering place, and meetings were generally held on the main street at the crossroads, outside the R.I.C barracks at Speaker's Corner. Shortly after O'Flanagan's arrival in Cliffoney, a new national school was opened.[25] He wrote to the owner of the old school, Colonel Ashley of Classiebawn castle and asked him to give the building to the villagers. Ashley complied and handed over the building, which was erected in 1824 by Lord Palmerston.[26]

A new school was opened in Cliffoney shortly after I went there. Thus the old school building which stood at the southwest corner of Cliffoney crossroads became vacant. The building itself belonged to Mr. Ashley, the Landlord. I wrote to Mr. Ashley and asked him to give the old school building for a parish hall. He was quite willing to give it, but the schoolmaster refused to give up the key. For years he had used the little playground of the school as a kitchen garden, and had driven the school children onto the public road. During the time that I was in Cliffoney the schoolmaster refused to give up the key. Some of the Irish Volunteers wished to break into the building by force, but in view of the fact that we had the other fight of the bog on our hands, I thought it was better to restrain them and do one thing at a time.[19]

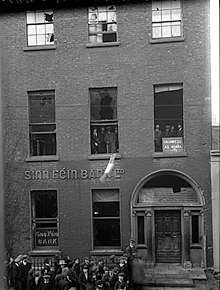

In gratitude the villagers named their new hall the Father O'Flanagan Hall and it soon became the home of the Cliffoney Sinn Féin club. During the Cloonerco Bog protest a large stack of turf, draped with a tricolour, was built outside the hall.[24]

Afterwards, the building was renovated, gaily decorated and painted in green, white and gold and made a Sinn Fêin hall. When opportunity presented it was an instruction and training hall for the Volunteers. It was burned In October, 1920, by British forces.[27]

The Father O'Flanagan Hall was used for drilling by the Cliffoney Volunteers, who also held dances, concerts and plays. It was burned by the Auxiliaries at the end of October 1920 in reprisal for the Moneygold ambush a few days earlier.[28]

O'Donovan Rossa funeral

.jpg)

At the end of July O'Flanagan was invited, at the request of Mary Jane O'Donovan Rossa, to speak at the funeral of her husband the veteran Fenian Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa.[29] O'Flanagan had visited the O'Donovan Rossa family during his travels in America.[12]

For a while Tom was considering who he would select to deliver the oration at the graveside, and finally decided on P. H. Pearse as the best available orator. It was a choice between Pearse and Father Michael O'Flanagan.[30]

O'Flanagan posed for a photograph with Mary Jane and Eileen O'Donovan Rossa, and Tom Clarke, the notoriously camera-shy organiser of the funeral and subsequent Easter Rising.[31] O'Flanagan then delivered a passionate oration to a select group of Irish Volunteers and nationalists at the reception of O'Donovan Rossa's remains to the lying-in-state in Dublin City Hall.[32] Countess Markievicz was so profoundly moved by his speech that she began to consider converting to Catholicism.

At the present time, nationality is in the ascendant. Its stock has gone up in the market. Perhaps some of the bidders are hypocrites, but the fact that they are compelled to bid shows that nationality counts for a great deal in the world today. But the men of Ireland should make it clear that the principles of nationality are no less sacred by the shores of the Atlantic than they are along the slopes of the Carpathians, or by the shores of the Danube; that if we have great powers in the world today who profess that they are fighting for the liberty of small nationalities, and that if these powers are not sincere in their professions, that we shall do our part to tear the mask of hypocrisy from their faces.[32]

The following day O'Flanagan accompanied the O'Donovan Rossa family to Glasnevin Cemetery where he recited the final prayers in Irish by the graveside standing beside Patrick Pearse who then made his iconic speech.[23]

Sligo Tillage meeting

On 9 October 1915 O'Flanagan attended a "tillage meeting" in Sligo court house. "Chaired by Canon Doorley, later bishop of Elphin, the meeting was packed with official personages such as the crown solicitor for Sligo T. H. Williams and the RIC district inspector, O’Sullivan."[6] A campaign was under way to encourage increased tillage cultivation to support the war effort. The main speaker was T. W. Russell, the Minister of Agriculture, who proposed a motion to that effect. O'Flanagan proposed a counter-motion to the effect that Russell's motion should be rejected without radical land reform, and went on to denounce the war and conscription.[19]

In O’Flanagan’s view, Russell’s plea for an increase in grain production meant no more than a small respite in the case of shortage. ‘Instead of commencing to starve on the 5th of January 1917, we shall be able to keep body and soul together for fifteen days more.’

Clearly O’Flanagan did not expect his proposal that a million a day be devoted to tillage in Ireland and England would pass into effect. And so he recommended people to ensure that famine was kept from their own doors. They should ignore the Board of Agriculture and adopt their own remedy..... They should ‘Stick to the oats.’ This call has ever since been associated with the curate of Cliffoney.

O’Flanagan’s speech ended with a rousing call: ‘The famine of 1847 would never have been written across the pages of history if the men of that day were men enough to risk death rather than part with their oat crop. Let each farmer keep at least as much oats on hand to carry himself and his family through in case of necessity till next years harvest.’[6]

He said that Irish people should stay out of the war not of their making, and to raise plenty of crops to be kept at home to feed the many native people in want. His motion was ignored. His speech was reported in the local papers and the following morning the RIC visited Bishop Coyne at his residence in St. Mary's.

The Cliffoney Rebellion

Within days of the Sligo meeting O'Flanagan was transferred to Crossna, County Roscommon. The people of Cliffoney responded to his removal by locking the church, an incident which became known as the "Cliffoney Rebellion". On the morning of 17 October, the key of the sacristy was taken; the door of the church was nailed shut from the inside and the new priest, Fr. C. McHugh was denied entry.[24]

The villagers began kneeling outside the church door each evening to say the Rosary for the return of O'Flanagan. They marched en masse into Sligo to interview the Bishop, who made himself absent. They also as sent a petition to the Pope, but nothing came of this. The Bishop refused to back down, or to meet the villagers and the rebellion continued through the autumn of 1915.[6] Eventually the church was opened after ten weeks, when O'Flanagan intervened in the dispute and appealed to the villagers to open the church for Christmas as a present to him. The door was unlocked on Christmas Eve 1915.[19]

Crossna

On 25 November 1915, O'Flanagan delivered a lecture entitled "God Save Ireland" to a packed audience in St. Mary's Hall, Belfast at a commemoration for the Manchester Martyrs.

On January 1916 he took the train to Cork where he spoke to a monster crowd at an anti-conscription meeting chaired by Thomás MacCurtáin—later assassinated by Crown forces—and policed by Terence MacSwiney who would die in 1920 after a 74-day hunger strike.[33]

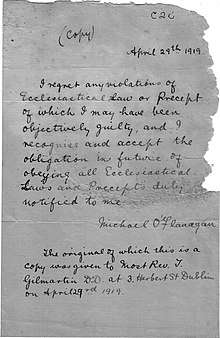

O'Flanagan's fiery speech was recorded by the RIC and widely reported in the national press. Upon his return to Crossna he was sanctioned by Bishop Coyne, who sent O"Flanagan a letter on 14 January 1916 stating:

I regret exceedingly that I find it necessary - in the interests of religion, ecclesiastical discipline and good order - to withdraw from you as I do hereby and until further notice, permission to preach anywhere in this diocese: - as also to celebrate mass outside the parish of Ardcarne without my permission in writing......

Finally I must forbid you to deliver any public lecture or address, or to remain a night outside the parish of Ardcarne without my special permission in writing.[Fr. Michael O'Flanagan, letters, 1915 - 1920 1]

The letter concluded, "I remain your grieved and afflicted Bishop, signed Bernard Coyne."[6]

He was invited to speak at a gathering of the Volunteers in Dundalk, but declined, sending a copy of the Bishop's letter to illustrate his problem. O'Flanagan, sometimes ignored the Bishop's orders, and presided over meetings at Ringsend and Donnybrook in Dublin on Thursday 6 April 1916, shortly before the Rising. The meetings were in protest against the deportation of Ernest Blythe and Liam Mellows. Among the speakers were The O'Rahilly and Thomas McDonagh; some 100 recruits were signed up for the Irish Volunteers.[34]

O'Flanagan spent the summer of 1916 in North Roscommon, and did his best to obey the Bishop's instructions. While living in Crossna he became friends with Patrick Moran. When a company of Volunteers was formed in the area, Moran, a member of the Volunteers procured sixteen rifles which were transferred from Dublin to Carrick-on-Shannon by O'Flanagan.[35]

He wrote and published many articles in the papers and journals, and outraged nationalists with a letter to the Freeman's Journal in June 1916 where he considered the implications of David Lloyd George's proposal to implement the 1914 Home Rule Act outside the six counties.[36] O'Flanagan "saw no point in basing a claim for self-determination for Ireland as a political unit on the assertion that Ireland is an island with a definite geographical boundary. Such an argument, he suggested, if made to influence continental nations with shifting boundaries, would have no force whatever."[37]

We can point out that Ireland is a nation with a definite geographical boundary… National and geographical boundaries scarcely ever coincide; geography would make one nation of Spain and Portugal history has made two nations of them. Geography did its best to make one nation of Norway and Sweden; history has succeeded in making two nations of them. If a man were to contrast the political map of Europe out of its physical map he would find himself groping in the dark. Geography has worked hard to make one nation out of Ireland; history has worked against it.

The island of Ireland and the national unit of Ireland simply do not coincide. In the last analysis the test of nationality is the wish of the people… The Unionists of Ulster have never transferred their love and allegiance to Ireland. They may be Irelanders, using Ireland as a geographical term, but they are not Irish in the national sense…

We claim the right to decide what is to be our nation. We refuse them the same right. After three hundred years England has begun to despair of making us love her by force. And so we are anxious to start where England left off. And we are going to compel Antrim and Down to love us by force.[38]

"'If,' he concluded reasonably enough, 'there be two Ulsters, there must surely be two Irelands.' In response to the argument that Ireland was 'an historic, economic, social and legal entity,' O'Flanagan responded by claiming that for centuries the country had been 'an historic and social duality,' and was now merely a portion of another economic and legal entity, the United Kingdom."[37] "Father O’Flanagan had the courage to recognise the complication that confronted Nationalist Ireland if it wished to build a single state on the island. That complication was there long before Father O’Flanagan recognised it and would have been there even if he had never acknowledged its existence."[36] Though he was ridiculed by fellow nationalists, who threw this letter back at O'Flanagan many times over the following years, another Vice-President of Sinn Féin, Martin McGuinness eventually came to the same conclusion in 1998:

“I recognise that there are one million people on this island who are British and let me state here and now that as a proud Irish Republican I not only recognise the unionist and British identity, I respect it. People who think that a new Ireland, a united Ireland can be built without unionist participation, involvement and leadership are deluded… The war is over and we are in the process of building a new Republic.” [36]

Easter Week

O'Flanagan was in great demand as a speaker at events and meetings: "Invitations poured in upon me from all over Ireland. I was getting tired of trying to explain how the Bishop had forbidden me, and why I continued to act in obedience to his prohibition."[19] He was taken by surprise by the events of Easter Week, when many of his friends from the Irish Volunteers and the Gaelic League launched an armed insurrection in Dublin.

He had been invited to Athenry in County Galway to review a parade of Volunteers on Sunday 23 April 1916. However he did not feel he could make the journey there and back without drawing the Bishop's censure and so he stayed in Crossna, where he remained for the week.[19]

Next day the Insurrection broke out in Dublin. All week our little Company of Volunteers awaited orders. They were ready to undertake anything, but the orders never came. There were no Irish Volunteers organised nearer than Ballaghadereen, Tobercurry and Ballymote. The general sympathy of the people of Crosna was of course, with the men of Easter Week. The same was true of every place where the propaganda of the Irish Volunteers had been carried on. And even in places where people were left to their own instinct, the only criticism was the criticism of an old man from a neighbouring district, who said “Ah! Poor fellows, they made the burst too soon.”[19]

O'Flanagan was friends with many of the leaders of the Easter Rising, and had met with many of them at the O'Donovan Rossa funeral, where he was photographed with both Tom Clarke and Padraig Pearse. "Fr. O'Flanagan realised that unless something was done immediately to exploit the inspiration of the men of Easter Week, and the abhorrence of the executions, the drift into political normality, as shown in West Cork, would be unstoppable."[4] O'Flanagan was vocal in his support for the sacrifice of the men of Easter Week."1916 was lost were it not for him. When the rest of the leaders were in jail he did what needed to be done."[13] Years later in the radio recording made to commemorate the First Dáil, he remarked:

For months it seemed as if Easter Week might be followed by a period of deep despair. Would the inspiration of the example of the men of Easter Week, or the terror caused by their defeat, have the greater effect upon the mind of the country? For nine long months this question received no clear and convincing answer. In January, 1917, and opportunity of solving the doubt occurred at the by-election. A candidate was carefully chosen whose election would be a clear proof that the hearts and minds of the people of Ireland were with the men of Easter Week.[4]

In a letter to Alice Stopford Green dated 30 July 1916, containing signatures collected for the petition to reprieve Sir Roger Casement, O'Flanagan expressed his admiration for "the men of Easter Week," commenting:

Some of us do not like the quasi apology for the execution of the Irish Volunteer Leaders, insinuated in the fourth paragraph but we are willing to waive that point for the purpose of doing our part for Roger Casement. The men who were executed in Dublin are to us martyrs & heroes, & the Government that ordered their execution are guilty of a great crime.[39]

The Election of the Snows

In December 1916 the Irish Parliamentary Party member for North Roscommon, the old fenian James O'Kelly died and his seat became vacant. A by-election was scheduled for February 1917 and O'Flanagan, forbidden to leave North Roscommon took full advantage of the situation.[40]

Along with J. J. O'Kelly and P. T. Keohane, O'Flanagan proposed Count George Noble Plunkett, father of the executed 1916 leader as a candidate, as "the passport to the situation at the time,"[6] and they wrote to the Count, then under house arrest in Oxford, inviting him to stand for the North Roscommon seat.[41]

Noting these preparations Bishop Coyne issued a warning by letter to O'Flanagan on 21 January 1917, beginning "In view of the present political unrest in part of the country, and to prevent any misunderstanding in the future, I would like to call your attention to the following statute on the national Synod of Maynooth (Page 121, No. 379)." Citing four statutes in Latin the Bishop's letter concludes: "Non-compliance with the terms of these statutes will mean, in your case, an "ipso facto" suspension, and deprivation of the ordinary faculties of the diocese. I am, B. Coyne."[Fr. Michael O'Flanagan, letters, 1915 - 1920 2]

O'Flanagan, meanwhile, was busy organising and coordinating the campaign as events unfolded. He wrote to his friend John Silke of Castlerea, asking him to "kindly get as much money as you can and send it to me for deposit with sheriff on behalf of Count Plunkett. It must be deposited with sheriff in Boyle before 2 o'clock on Friday 25th inst."[4] On 27 January O'Flanagan wrote twice, sending a letter-card to both Oxford and Dublin, with arrangements for Count Plunkett to speak in Boyle and Ballaghdereen: "I have written to you in Oxford asking you to come to Boyle by the train that leaves Broadstone at 9 a.m. on Thursday & to speak there and at the fair in Ballaghadereen next, lest you might have left Oxford I am also writing this to Dublin."[42] Indicating the importance of the Catholic church in elections, he adds that they are planning to hold meetings at some 25 churches the following day.

The campaign became known as the Election of the Snows on account of the adverse weather conditions which saw snow drifts of up to ten feet high blocking the roads.[43] O'Flanagan, though forbidden to speak outside the boundaries of the parish, was at the forefront in running the campaign for the Count, which included the organisation of clearing the snow off the roads so that supporters could get out to vote.[2] Count Plunkett only arrived two days before election day.[4] O'Flanagan was joined by Seamus O'Doherty, a native of Derry, who became director of elections for the Count[35] and Laurence Ginnell, the rebellious independent MP for Westmeath, who became Plunkett's election agent.[43] They were joined by workers from Dublin and other parts, such as Michael Collins, Arthur Griffith, Larry Nugent, Rory O'Connor, Darrell Figgis, William O'Brien, Kevin O'Shiel, Joseph McGrath and Count Plunkett's daughter Geraldine with her husband Thomas Dillon.[6]

After the election the Irish Times commented "For twelve days and nights he was up and down the constituency like a whirlwind and talking to people at every village and street corner and crossroads where he could get people to listen to him."[35]

The winner was Count Plunkett, who took the seat by a large majority, the tally being Plunkett: 3,022; Devine: 1,708; Tully: 687.[13] Count Plunkett and O'Flanagan were "chaired" from the courthouse to a celebration where Plunkett surprised his audience by announcing he would abstain from Westminster.[43] That night O'Flanagan travelled to Dublin and left an unpublished description of the journey:

That night I went to Dublin by motor car. The road from Boyle to Carrick had been well cleared of snow and the fall in the country east of the Shannon was not great. However, the night was intensely cold. I sat in the front seat of the car until we reached Mullingar.

We stopped for a while in Carrick, Longford and Mullingar and with this advantage added to the protection of the windscreen, I had a tolerable time of it up to there. But in Mullingar, I took pity on Arthur Griffith. He was one of those in the back seat. He still wore the beard which he had grown during his time in prison.

The valleys through which we passed were filled with a bitterly cold frozen fog and Arthur was covered with ice like a picture of some man on an Arctic expedition. As soon as we passed Maynooth we all got out and ran through the snow for over a mile in order to get our blood in circulation. When we reached Dublin it was five o'clock in the morning.[44]

The Plunkett Convention

The reflected glory of his sons, together with some fiery speeches of his own and a genuine distaste for any sort of compromise made Plunkett the temporary spokesman of the radical republicans. There can be little doubt that many of them exploited him. On the other hand, new bonds were established, and the Roscommon campaign brought together three very different figures—Plunkett, O'Flanagan and J. J. O'Kelly—who over the next two decades would come to represent irreconcilable, fundamentalist republicanism.[5]

On 19 April 1917 Count Plunkett chaired a Convention of advanced nationalists at the Mansion House in Dublin in an attempt to seek common ground in the aftermath of the North Roscommon election victory.[41] There were tensions between Count Plunkett and Arthur Griffith, as to the form and direction the movement should take and who should be in charge.[5] Count Plunkett wanted to establish branches of his Liberty Clubs throughout the country, while others present felt they should more usefully continue to use the name and organisation of Sinn Féin.[43] A split seemed imminent.

Fr. Robert Fullerton proposed that O'Flanagan to mediate between the two groups and prevent a split. O'Flanagan reached an agreement with Griffith, and they proceeded with the meeting, though later that evening O'Flanagan had to break up a row between Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith at a post convention gathering at Count Plunkett's residence.[5]

A compromise "rainbow" committee was formed represented by members from all sides: Plunkett, O'Flanagan, Cathal Brugha and Thomas Dillon representing the republican wing, Arthur Griffith and Seán Milroy for Sinn Féin, Thomas Kelly and William O'Brien representing the Labour movement and Stephen O'Mara for the Irish Nation League. O'Flanagan proposed Countess Plunkett to represent the women of Ireland. This group became known as the Mansion House Committee.[6]

The authorities of both Church and State were concerned by O'Flanagan's activities and the RIC kept notes of his movements and speeches.

Sinn Féin revival 1917

The Mansion House Committee met five times. Their brief was to plan the forthcoming by-elections and organise a deputation to plead Ireland's case at the Paris Peace Conference at the end of the war. They also issued a statement rejecting any contact with Lloyd George's proposed Irish Convention chaired by Sir Horace Plunkett. As the 1916 prisoners were released over the summer of 1917, a number were co-opted onto an expanded committee.[6]

Another by-election was held in South Longford in May 1917 and republican prisoner Joseph McGuinness was put forward. Neither McGuinness nor Éamon de Valera, who was leader of the prisoners were keen on contesting, being wary of constitutional politics. The election was under the slogan "Put him in to get him out".[5]

O'Flanagan was forbidden by the Bishop's restrictions to participate in the election campaign, which he found profoundly frustrating. "I did not think the time had come to break the muzzle and had to stay away from Longford," he remarked later in December 1918.[12] McGuinness won by the narrow margin of 37 votes after a recount.[5] Successes in North Roscommon and South Longford persuaded de Valera to go forward in East Clare and he too was successful.[4] Another by-election in Kilkenny was then won by another volunteer, W. T. Cosgrave, who had been preferred to Arthur Griffiths as a candidate.[40]

Thomas Ashe, arrested for making a seditious speech, died while being force-fed in Mountjoy Prison on 25 September. Requiem Mass was celebrated at the Pro-Cathedral by O'Flanagan on Friday morning before removal to City Hall where his body lay in state for two days.[45] Ashe's remains were followed by a procession of 30,000 who marched to Glasnevin cemetery where Michael Collins gave the graveside oration.[46]

Vice-President of Sinn Féin

A convention was held at the end of October 1917, where the Easter Rising veterans and other supporting groups merged with Arthur Griffith's older organisation and adopted the name of Sinn Féin.[46] Despite expectations of a split, Arthur Griffith and Count Plunkett stepped aside allowing de Valera to become president, with Griffith and O'Flanagan elected vice-presidents for a three-year term.[5] "Long-term friends of Griffith in Sinn Féin, auch as Alderman Tom Kelly, Robert Brennan and Jennie Wyse Power, remained the party's directors of elections, but this responsibility was taken on more by newcomers such as Fr. O'Flanagan who, in the absence of a chief whip (this was not a parliamentary party), was effectively the party's chief organiser."[47] O'Flanagan proved a highly effective organiser and party manager.

On the same day the Irish Convention published their report the British Government decided to impose conscription on Ireland. The resulting backlash brought all the diverse nationalist strands together, including the Catholic church leaders and the Irish Party, united in a massive anti-conscription protest campaign. When the Military Service Act was passed in the House of Commons on 16 April 1918, John Dillon led the IPP members out in protest and they returned to Ireland to join the campaign.[40] O'Flanagan had a long record of protesting against conscription dating back to his time in Cliffoney at the start of the war. He spoke at the conclusion of the monster rally in Ballaghadereen on 5 May, where John Dillon and Eamon de Valera shared a platform for the first and only time.

When the Sinn Féin leader finished his speech and sat down, O'Flanagan of Crossna commented that what was represented on stage was ‘Ireland a Nation’ and it served as a symbol both of hope and confidence ‘to see united in conference men like John Dillon and William O’Brien, with [and here he pointed at de Valera] that brand that was snatched from the burning of Easter week and saved by Almighty God to be the hero leader of the young blood of Ireland’.[48]

In response to this wave of protest, Lord French's German Plot was set in motion, when old letters belonging to Sir Roger Casement were resurrected and used as flimsy propaganda.[49] On 16 and 17 May sixty-nine Sinn Féin leaders were arrested and imprisoned by Crown forces, or went on the run if they had been tipped off by Michael Collins. O'Flanagan was exempted because he was a priest, and was left as the acting-president of the party.[46] Sinn Féin issued a statement:

Anticipating such action, the Standing Committee of Sinn Féin nominated substitutes to carry on the movement during the enforced, and what may be, the temporary exile of our leaders. The country may rest assured that no matter how many leaders may be arrested, there will be men and women to take their places. All that we need is to continue to follow the latest advice of de Valera, namely, to remain calm and confident. - Michael O'Flanagan, C.C.[46]

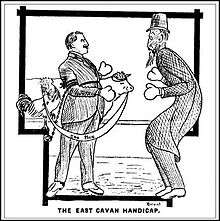

East Cavan By-election

In early 1918 Sinn Féin contested and failed to win three by-elections in South Armagh, Waterford and Tyrone. Another important by-election occurred on 20 June 1918 in East Cavan. With most of the leading Sinn Féin members in prison as a result of the German Plot, seasoned campaigners were in short supply. O'Flanagan was approached by Andy Lavin and asked to canvas for Arthur Griffith, then incarcerated in Gloucester prison.[43]

.......and just then, miracle of miracles, Sinn Féin found its champion. He burst on the scene, the greatest orator since O’Connell, a priest - Father O’Flanagan. He went through Cavan like a torchlight procession. Young Sinn Féiners were no longer stumbling. Sinn Féin had made a happy choice of candidate - Arthur Griffith. He was not dependent on “put him in to get him out”. O’Flanagan took party speakers head on: the phoney German plot was a first step in preparing the, ground for conscription. His powerful voice fairly bungled his message. The battle against conscription would be decided not on the floor of the British House of Commons, but here on the fields of Cavan.[50]

He broke the Bishop's "muzzle" and delivered a vitriolic speech to 10,000 people at Ballyjamesduff on Sunday 26 May.[51] The oration, which was suppressed by the censor, was printed and distributed widely as by Sinn Féin as "Father O'Flanagan's Suppressed Speech."[52]

The police also kept a close eye on proceedings and in some places monitored the movement of motor cars, noting the vehicles’ numbers and checking drivers’ licences. In one instance, in Bailieboro, a car was stopped in the early morning bearing the inscription on its number plate ‘I.R. 1916’. When quizzed, the occupants produced a permit signed ‘M. O’Flanagan, C.C.’.[53]

O'Flanagan put terrific energy into the contest, and featured widely in both RIC and newspaper reports, always helpful for propaganda: "it was reported from Ballyjamesduff that a victim of paralysis has been visited by O'Flanagan and that, a few days after receiving the priest's blessing, the man was able to walk a short distance. With such advantages Sinn Féin could not lose."[5] O'Flanagan had the satisfaction of seeing his fellow Vice-president win by a comfortable majority.

Fr. O'Flanagan spoke five or six times a day: the election workers were out at dawn, and were still at it in village and townland and hillside farm when darkness fell. They did it. Arthur Griffith, even in that Hibernian stronghold, got 3,785 to the Irish Party’s O’Hanlon 2,581.[46]

As a result of his appearance in Ballyjamesduff, O'Flanagan was suspended from his clerical duties by Bishop Coyne.[12] "Father O’Flanagan has in fact, been more harshly treated by his own Bishop than the other Sinn Féin leaders have been treated by the British Government."[54] When the people of Crossna discovered his suspension, they promptly followed the example set the Cliffoney villagers and locked Crossna church in protest.[43] The Crossna Rebellion received widespread newspaper coverage. The villagers wrote a strongly-worded remonstrance in censure of the Bishop's actions, which was published in local newspapers. the end of which reads:

The insults that are now poured on Fr. O’Flanagan will do him no harm. A grateful and warm-hearted people will only cling more tightly to him in the hour of his affliction. And whether your Lordship took dictation from non-Catholics such as Lord Middleton, or from influential Catholics, such as the Anglicised Sir Thomas Stafford, it matters little.

When these calumniators are dead and gone, and when their names shall only be recalled with horror and disgust, the name of the patriot priest of Crossna will shine as bright and clear on the pages of Irish history as the morning star that circles the heavens, pointing out to future generations of Irish men and women the road to glory, to honour and to virtue.

And as a protest against your Lordship’s action, we have closed Crossna church, and it will remain closed till Fr. O’Flanagan is restored to the mission. Your Lordship may look on our action as extreme, but pray remember the awful malediction conveyed in those dreadful words: “Woe to the man whom history shall accuse and whom posterity shall judge.” To this tribunal we leave your Lordship’s action and our own.[35]

However, as with the Cliffoney Rebellion, the Bishop refused to negotiate or reinstate O'Flanagan. The church was opened after three weeks at O'Flanagan's request.[12]

Freedom of Sligo

In late on Sunday 23 June O'Flanagan was awarded the Freedom of Sligo in recognition of his contribution to the nationalist cause. He made a public speech before a massive crowd on the steps of Sligo Town Hall.[55] The RIC recorded his speech and estimated that there were at least 2,000 people in attendance.[2]

As a result of his suspension O'Flanagan threw his time into his Sinn Féin work, residing in Dublin. He had no income at this time and a group of supporters in Crossna raised a subscription called the Father O'Flanagan Fund which was widely advertised in the national and regional newspapers.

General Election 1918

The Sinn Féin Ard Feis took place in the Mansion House on 29 October. With most of the leadership in prison, O'Flanagan chaired the meeting and gave the main address. As expected, when the war ended the first general election since 1910 was called.

On 11 November, coinciding with Armistice Day, Sinn Féin convened again to launch their General Election campaign. "An important part of Sinn Féin's preparations for the election was the completion of a manifesto and once again the radical republican influence of Boland, Collins and Father O'Flanagan was visible."[40]

"As many of the Sinn Féin members were in jail it fell to leaders outside, such as Mick Collins, Harry Boland, Diarmuid O'Hegarty, Fr. O'Flanagan, Jennie Wyse-Power and Hannah Sheehy Skeffington, to select candidates and promote their campaign."[47] O'Flanagan toured the length and breadth of the country as one of the main and most popular public speakers for Sinn Féin. There are numerous accounts of his speeches and journeys scattered throughout the Bureau of Military History witness statements. He was usually accompanied by members of the Irish Volunteers for bodyguards.[21]

Fr. O'Flanagan's involvement in the 1918 campaign reproduced on larger scale the "Election of the Snows" in North Roscommon. He travelled from Cork to Donegal, from the Falls Road to Wexford Town in the four-week election campaign. Sometimes he spoke five or six times a day. Everywhere—or, rather, almost everywhere—he was acclaimed with enthusiasm.[6]

The campaign coincided with an outbreak of influenza, and many people died throughout Ireland. The 1918 election was fought under a franchise tripled in size, allowing women and many younger men to vote for the first time. O'Flanagan spoke at Ballaghadereen where he spoke of the sacrifice of the men of 1916 and castigated the leadership of the Irish Party for encouraging conscription:

At a rally in Ballaghadereen, the home town of John Dillon, O'Flanagan contrasted the record of the Irish Party with that of 'the men of Easter Week who really saved Ireland'. On the one side were those who strove to enlist the young men of Ireland in the British Army. On the other side were the insurgents of 1916 as well as some old Fenians and 'some mad curates with them'.

While the leaders of 1916 were dead or in prison, their followers were free. While the leader of the Irish Party and his two sons were very much alive 'his followers (were) dead in the Dardanelles or in Flanders…' The protest of 1916 had ensured that many thousands resisted enlistment…[6]

When the polling took place in December, Sinn Féin swept the boards, completing the process begun in North Roscommon, decimating the Irish Parliamentary party by taking 73 of the 105 seats available.[5]

At the end of the 1918 election O'Flanagan remarked that "the people have voted Sinn Féin. What we have to do now is explain to them what Sinn Féin is."[5]

Chaplain to the First Dáil

The successful Sinn Féin candidates abstained from Westminster and instead proclaimed an Irish Republic with Dáil Éireann as its parliament.[28]

The First Dáil's inauguration took place in the Mansion House in Dublin on 21 January 1919. "The majority of the 103 members returned in the 1918 election were not present – some by choice, others through force of circumstance, their absences recorded in the recurring phrase of that day ‘faoi ghlas ag Gallaibh.'"[56] Harry Boland and Michael Collins were absent, having travelled to England to engineer de Valera's escape from Lincoln prison.[49]

O'Flanagan was appointed chaplain to the First Dáil. He was introduced by the chairman Cathal Brugha as "the Staunchest Priest who ever lived in Ireland," and invited to open the proceedings with a prayer.[3] He duly read a prayer in both Irish and English calling for guidance from the holy spirit. The opening of the First Dáil coincided with the outbreak of the War of Independence when two policemen were shot dead in Tipperary that afternoon.[28]

O'Flanagan attended a meeting of the Dáil in early April, attended by a larger number of TDs including escapee de Valera, Collins and Boland. The event was photographed for publicity and was printed as a poster and postcard.[57]

In early May the Irish American delegation visited Dublin on their return from a fruitless mission to the Paris Peace Conference. The delegates, Michael F. Ryan, Edward Dunne and Frank P. Walsh posed for a photograph with senior members of Sinn Féin. O'Flanagan is standing with Count Plunkett and Arthur Griffith, accompanied by Éamon de Valera, Lawrence O'Neill the Lord Mayor of Dublin, and possibly W. T. Cosgrave, on the steps of the Mansion House.[58]

On 19 May 1919, after a protracted period of negotiations involving the intercession of Archbishop Gilmartin of Tuam, O'Flanagan was restored to his full status as a priest. He was sent to Roscommon Town to resume his clerical duties. As a member of the Dáil's Land Executive he was responsible for propaganda and agriculture in County Roscommon. An illustration in the National Library of Ireland shows him attending a meeting the Dáil, chaired by Count Plunkett, on 21 June 1919.[59]

Raid on O'Flanagan's rooms

Violence and reprisals continued to escalate throughout the country in late 1920. On 11 October Fr. O'Flanagan was arrested by Crown forces on his way to a meeting of the Ballinasloe Asylum Committee, but was released within a few hours.[60]

On Friday 22 October, O'Flanagan's rooms in Roscommon were raided by two members of the Auxiliaries, accompanied by two RIC officers. They took books, papers, confiscated his typewriter, chopped up a suitcase of vestments, and stole a £5 note. The incident is recounted in the witness statement of John Duffy, one of the R. I. C. constables present.[61] O'Flanagan's secretary and typist Vera McDonnell also left a record of the raid:

The door of the Curates' house was opened by Fr. Carney, the other curate, and the Auxiliaries proceeded to search Fr. O'Flanagan's rooms. They pulled the place asunder and read all his letters. O'Flanagan was interested in the derivation of Irish place names and, for that reason, he used to buy old Ordnance survey maps at auctions. He had shortly before bought some belonging to the County Surveyor who had died and pieces of these had been cut out apparently by the Surveyor for his own purpose.

The Auxiliaries came to the conclusion that Fr. O'Flanagan had cut them out for the I.R.A. for the purpose of attacks on the Crown forces. They told me if they got Fr. O'Flanagan they would give him the same fate as they had given to Fr. Griffin. They also told me to leave the town at once, and that my being a woman would not save me from being put up against a wall and shot. During all this time Fr. Carney remained in his own rooms and was not molested.[62]

Three nights later on 25 October the Moneygold ambush took place three miles south of Cliffoney.[28] The local Volunteers, many of whom were friends of O'Flanagan, attacked a nine-man RIC patrol from Cliffoney barracks and shot four dead including the sergeant, close to Ahamlish graveyard.

Cliffoney and the surrounding area was raided on several subsequent nights at the end October as a company of Auxiliaries based at Coolavin came to north Sligo for reprisals.

"For miles around the scene the male population fled in terror and have not since returned," the County Inspector wrote on 31 October. "Splendid discipline was maintained by the forces but notwithstanding this some reprisals followed," the Inspector reported. "The houses of some leading suspects were burned as well as the Father O'Flanagan Sinn Féin Hall at Cliffoney".[63]

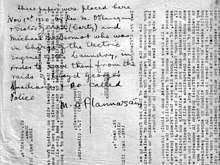

Several houses in Cliffoney were burned along with Grange Temperance Hall and Ballintrillick Creamery. Also burned in reprisal was the Sinn Féin hall at Cliffoney, named after Father Michael O'Flanagan. Painted on the ruined walls of the latter was a message for local republicans: 'Vacated home of murder gang.'"[28] On 1 November, the day of Kevin Barry's execution and Terence MacSwiney's funeral,[49] O'Flanagan took his personal papers and hid them in the laundry room at the convent in Loughglynn, with a hand-written cover note:

These papers were placed here Nov 1st 1920 by Rev. M. O'Flanagan & Sister Gerard (Carty) and Michael McDermot who was in charge of the electric engine of the Laundry, in order to save them from the raids of Lloyd George's Auxiliaries & so-called police. M. O'Flannagáin.[19]

Bloody Sunday took place on 21 November when thirteen members of the Crown forces, sixteen civilians and three republican prisoners, including Dick McKee and Conor Clune, were killed.[49] "On November 28, Commander Tom Barry's Flying Column lured two trucks carrying nineteen officers from C Company of the Auxiliaries into an isolated killing zone at Kilmichael, County Cork, and wiped them out, killing seventeen and seriously wounding two."[64]

Telegrams to Lloyd George

O'Flanagan was Acting-President of Sinn Féin while de Valera was in the United States and Arthur Griffith was in prison. On 6 December, responding to comments about peace made in the press by Prime Minister Lloyd George, O'Flanagan began a public dialogue through the medium of telegrams and newspapers.[46] The first message ran "you state that you are willing to make peace at once without waiting for Christmas. Ireland is also waiting. What first step do you propose?"[6]

These unexpected and unsanctioned moves caught his colleagues in Sinn Féin by surprise and they were quick to distance themselves from his comments. His critics, including Michael Collins, who was conducting his own secret peace moves through Archbishop Clune, was not impressed.[49] "Collins made certain that the press was informed that O'Flanagan had acted unilaterally, writing in disgust, 'We must not allow ourselves to be rushed by these foolish productions or foolish people, who are tumbling over themselves to talk about a truce, when there is no truce.'"[64] Collins and Griffith had been holding meetings with Archbishop Clune, who had been sent over by Lloyd George to negotiate terms of a truce. Lloyd George took O'Flanagan's messages as a sign of disunity among the leaders of Sinn Féin, and promptly changed the terms of his deal with Clune to include a surrender of weapons.

"A later comment by O'Flanagan suggests that his cable was a deliberate attempt to sabotage Clune's efforts, which he held to be too much influenced by Dublin Castle."[65] He continued his dialogue with the British Prime Minister until de Valera's return from America on 23 December.

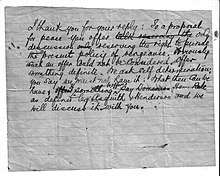

I thank you for your reply: To a proposal for peace you offer only discussion reserving the right to pursue the present policy of vengeance. Obviously such an offer could not be considered. Offer something definite. We ask for self determination; you say we must not have it. What then can we have, if something be offered, say Dominion Home Rule as defined by Asquith & Henderson we will discuss it with you.[66]

De Valera arrived back in Ireland on 23 December, the day the Government of Ireland Act was passed, dividing the country in two. It was "because de Valera anticipated that the British government would soon attempt to resolve the Irish situation through placing an emphasis on church diplomatic channels that he considered that the Dáil had to be fully prepared for this eventuality by having as strong a rapport with the church as possible. For this reason, although de Valera dissuaded Fr. O'Flanagan from continuing the peace negotiations, he only censured rather than expelled him from Sinn Féin for having bypassed the authority of the Dáil."[47]

De Valera used O'Flanagan to hold informal talks with Lloyd George in early January, where they discovered that Dominion status for Southern Ireland was the most that the British were prepared to offer.[67] In late January 1921, O'Flanagan and judge James O'Connor met informally in London with Sir Edward Carson to discuss a peaceful solution to the conflict, but without success.[68] O'Flanagan's movements and meetings were recorded and reported by detectives from the RIC.[49] His importance as a peacemaker at this point was recognised by Lloyd George, who suggested confidential meetings by:

- (1) a meeting between de Valera, O'Flanagan, O'Connor, Carson and Craig, to be followed by a meeting between the above five and the Prime Minister and Bonar Law; or, at de Valera's option, (2) a meeting between de Valera, O'Flanagan, O'Connor, the Prime Minister and Bonar Law in the first instance.[69]

However these options were not taken up by De Valera.

Lloyd George and his cabinet then intensified the conflict and the last six months of the War of Independence were the most violent. On Monday 14 March 1921 O'Flanagan's friend, Patrick Moran from Crossna, was executed in Mountjoy Jail for several murders.[35] "The next challenge which faced the Sinn Féin party came in May 1921, and it consisted of general elections for two separate 'devolved' parliaments in Dublin and Belfast."[5]

Republican Envoy

At the Sinn Féin Ard-Feis at the end of October 1921, O'Flanagan was selected to travel to America as a Republican Envoy.[12] After some difficulties about his passport and status, he landed in the United States in November. He was filmed and interviewed by British Pathé on his arrival in New York.[70]

O'Flanagan was touring the east coast giving lectures and getting plenty of newspaper coverage in his mission "to help in raising the second external bond certificate loan of Dáil Éireann," when the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed on 6 December 1921.[71]

It has been said of Sinn Féin that Arthur Griffith designed it, was the great architect; that Father O’Flanagan was the builder, constructing it into one harmonious whole; and that to de Valera was left the guiding of the machinery....[72]

By January 1922 Sinn Féin had divided on the issue of the Treaty. O'Flanagan and his friend and fellow envoy John J. O'Kelly (Sceilg) were strongly opposed to the Treaty, and refused to accept the validity or authority of the Free State.

In 1922 an article by O'Flanagan titled "Co-operation" was published as a sixteen-page booklet by Cumann Leigheacht an Phobail in Dublin. The article discusses the economic and human value of Co-operative Societies for Ireland.[73]

Australia

In March 1923, two representatives of the Irish republican movement arrived in Australia. They had travelled from the United States, and they were on British passports which had been issued in 1921. The Irish Envoys as they became known were Father Michael O’Flanagan and John Joseph O’Kelly. These were not men in the front rank of Irish republicans but neither were they far from the top.[74]

When O'Flanagan and O'Kelly arrived in Australia they met the Archbishop of Melbourne, Daniel Mannix. The Archbishop had been one of O'Flanagan's teachers in Maynooth and he was politically sympathetic to their mission. Before long they were arrested for making seditious speeches, and incarcerated for several weeks in "Botany Bay" before eventually being deported on 16 July.[75] They were sent to France before making their way back to the United States.[6]

Though he was absent from the country, O'Flanagan was re-elected as one of four Vice Presidents of Sinn Féin and as one of the nine members of the Officer Board at the Ard-Feis in early November 1924.[76]

Return to Ireland 1925

On 21 February 1925 O'Flanagan arrived home from the United States to help the third incarnation of Sinn Féin contest a number of by-elections. Reformed in 1923 by de Valera, the third Sinn Féin "was a coalition of different elements, and while it no longer included any non-republicans it remained an uneasy combination of extremists and (relative) moderates, of ideologues and politicians, of fundamentalists and realists."[5] Sinn Féin had won 44 seats in the August 1923 general election, but abstained from taking their seats in the Dáil.

O'Flanagan was vocal in his dismay about the state of the country after the Civil War, governed by the pro-treaty Free State with the support of the Catholic church. "In regard to the Free State he argued that nothing had changed since the days of the British regime — 'they have changed the label on the shop door and they have changed the display in the window, but when you go in to buy anything behind the counter you will find the same old stuff.'"[6]

He expressed equally radical views on the abuse of power within the Catholic church and was highly critical of ecclesiastical interference and control over temporal affairs. "During several by-election campaigns in 1925 O'Flanagan heaped abuse on Ireland's bishops for their extreme political partisanship. He denounced attempts to turn 'churches into political meeting places by making stupid, ill-informed political speeches from the altar.'"[77] O'Flanagan was outraged that the Sacraments were being used as a weapon, and that republicans were being harassed from the pulpits.

Referring to Denis Barry, a republican who had died on hunger strike in 1923 and whose funeral was barred from churches in his native Cork, Fr. O'Flanagan declared "'I would rather go to heaven with Denis Barry than go to hell at head of a procession of high ecclesiastics.'[6]

"The results of nine by-elections in March 1925, in which republicans secured only two victories, seem to have depressed de Valera considerably."[78] Increasingly disillusioned with Sinn Féin's policy of abstention he began to consider other means to enter the Free State parliament. In a clandestine visit to Rome to visit Monsignor John Hagan, de Valera worked out his formula to bypass the Oath.

De Valera tended to keep his friendship with Mgr Hagan a closely guarded secret in the 1920s. When the former visited Rome prior to the establishment of Fianna Fail in 1926 he was secretly housed in the rector's rooms in the Irish College and convinced by Hagan of the need to found a new party. Hagan, who was a regular visitor to the de Valera household when he was home on annual holidays, was also a substantial contributor to the coffers of the Fianna Fail party upon its foundation. He was a prelate who saw no contradiction in rendering to God and to Caesar.[79]

In April O'Flanagan was suspended from clerical duties by Bishop Coyne and forbidden to say mass, because of his outspoken nationalist activities and the anti-clerical speeches he had made in America and for delivering "dis-edifying harangues to excited mobs at five places in the diocese of Elphin."[80] His opinions, especially his views on the Catholic church alarmed some of the more devout and politically ambitious members of Sinn Féin. Silenced again, he maintained his radical stance on social issues writing a series of articles in the republican journal An Phoblacht between June and December 1925.[67]

In September "Fr. Michael O'Flanagan and Eamonn Donnelly TD and Republican MP for Armagh, were arrested by the RUC, at a concert at Derrymacash, near Lurgan, on September 26. Held overnight, they were put, next day upon a train for Dublin."[81]

Sinn Féin split 1926

On 9–11 March 1926, an extraordinary Ard-Fheis was summoned by de Valera.[78] There he tabled a proposal that Sinn Féin members should be free to enter the Free State Oireachtas if the Oath of Allegiance were removed. "He was prepared to 'take the risks and go after the people'; he would take 'the bog road' instead of 'the High road.'"[77] O'Flanagan possibly expected this, since rumours that "a number of Irregulars are in favour of entry to the Dáil" had been circulating since January. O'Flanagan tabled a counter motion stating:

That it is incompatible with the fundamental principles of Sinn Féin as it is injurious to the honour of Ireland, to send representatives into any usurping legislature set up by English law in Ireland.[82]

"O'Flanagan's motion was narrowly passed by 223 votes to 218, and de Valera resigned as President of Sinn Féin. In his resignation speech he claimed that 'the "Free State" junta [was] solidifying itself as an institution' and that the people would fall in behind it unless a republican party entered the political fray."[78] "The Ard-Fheis then adjourned to allow both sides to discuss their respective positions and Michael O'Flanagan observed that during this break Mary MacSwiney had acted in such a manner 'as to facilitate one section of the organisation in creating a division and establishing a rival organisation.'"[76] De Valera left to found Fianna Fáil, and the majority of the more talented members of Sinn Féin followed him, leaving behind the rump Sean Lemass referred to as a "galaxy of cranks."[77]

Bishop Coyne died of a seizure July 1926, and was replaced by Dr. Edward Doorly. On 20 October 1927 when his father Edward O'Flanagan died, the ban on O'Flanagan's ministry was revoked by Fr. Harte, allowing him to celebrate the funeral mass. Fr. Harte was vicar general while Bishop Doorly was away in Rome.[6]

O'Flanagan considered his ban removed, though he did not celebrate mass in public and was never promoted within the hierarchy. O'Flanagan remained with the reduced "galaxy of cranks" in Sinn Féin. From this time onwards he began to turn his attention towards his inventions and historical research.[12]

De Valera's new party quickly eclipsed Sinn Féin at the June 1927 election. It became obvious, with hindsight, that de Valera had engineered the split to suit his needs. "Father O'Flanagan, another strong opponent of de Valera's new policy, who remained in Sinn Féin, recalled bitterly that he and O'Kelly,"

had been made tools of by de Valera for working up an organisation in America for the followers of de Valera's policy to profit by. As soon as he and Sceilg (J. J. O'Kelly) had gotten things well under was in the USA, a slick little politician (Sean T. O'Kelly) was sent over.[78]

O'Flanagan remained friends with union leader James Larkin and though he expressed some Marxist sentiment, never joined any left-wing group. Having no clerical income while he was suspended, O'Flanagan travelled to the United States for a number of months each year, giving lectures on his historical work and the Irish political situation.[3] He produced a brochure in 1926 advertising lectures such as: Ireland Today, Political and Economic; Irish Literature, Gaelic and English; Ireland's Ancient Leadership in Europe. Illustrated with slides.[83] A lecture he gave at Tara Halls in New York, Thursday evening, 30 June 1927 titled "Church and Politics" was printed as a pamphlet and sold.[84]

In the part I took in the fight for the Republic in Ireland I was never afraid of the other side. I was not afraid of Redmond or Dillon, of Bishop or of Pope, but I was always more or less afraid of the people who were on my own side. I had reason to be, for many of them wavered. But there has always been this encouraging feature, that the wavering was greatest amongst the leaders, and least amongst the rank and file of the people.[85]

Inventions

O'Flanagan had a keen mind, and over the years he filed patents for a number of inventions. He applied for a patent for a gyroscopic travel bed designed for long-distance ocean voyages (of which he had plenty of experience) in 1923.

He filed patents for his most famous invention, a set of protective swimming goggles in 1926 and 1930.[86] In the late 1920s he was selling his goggles by mail order from his home in Bray, County Wicklow, advertising them in the Catholic Bulletin and on his lecture tours in the USA.[87]

A recent issue of the "New York Herald Tribune" contains an interesting article by Mr. John Elliott describing submarine "specs" invented by Rev. M. O'Flanagan, which enable swimmers and bathers to see below the surface of the water as well as they can above.

Mr. Elliott says "this invention is the result of almost twenty years' intermittent labour, following an inspiration that came to him (Rev. M. O'Flanagan) while he was visiting the Catalina Islands, off Lr. California, in 1908."[88]

In 1936 he patented his design for a cavity wall insulation product.[12]

Ordnance Survey letters

O'Flanagan became immersed in academic work at this time. He undertook editing the many hand-written volumes of the 1830s letters by John O'Donovan in Ordnance Survey of Ireland notebooks, a colossal project. Some of the papers had been stored at the Ordnance Survey depot in the Phoenix Park, and members of the Gaelic League, concerned had been attempting to make copies under the cover of Michael O'Rahlly's Irish Topographical Society. "The documents were stored in a wooden shed and could never be replaced if there was a fire."[89]

Between 1927 and 1932 he produced about 50 typescript editions of the Ordnance Survey Letters for each of the 29 counties for which they exist. These were typed in the Royal Irish Academy by Mary Nelson, Margaret Staunton and Maura Riddick. Beginning in 1932, Patrick Byrne (1912) typed the Name Books in the Ordnance Survey Office for O'Flanagan at a rate of 30 pages a day. A small edition of about six copies was bound in 150 volumes.[43]

"Their popularity is in many respects due to the indefatigable Father Michael O’Flanagan who, in the 1920s and 1930s, produced a number of typescript copy sets from the originals."[90] O'Flanagan oversaw the project, editing the handwritten letters into typed transcripts, making multiple copies for each county. These records are invaluable, and are still being used by Irish archaeologists, and O'Flanagan's name appears in the notes of countless papers as OS editor. In his 1927 lecture, Church and Politics, O'Flanagan describes how he funded the undertaking using a donation from supporters in America:

I was without means of support. I was compelled to subsist on the hospitality of my friends. You here in America took the occasion of the Silver Jubilee of my Ordination two years ago to present to me the very substantial sum of seven thousand dollars.

I did not care to accept this gift in a narrow personal sense. It has enabled me to safeguard some of the historical materials lying neglected in one of our Dublin Libraries. John O'Donovan, the famous editor of the Annals of the Four Masters, was one of the greatest Irish Scholars eighty or ninety years ago. He went around nearly every district in Ireland and collected the historical traditions handed down by word of mouth amongst the people. He spent seven years at this work.[80]

The first instalment was used to hire a typist who worked on the letters for the next two years. O'Flanagan placed copies in the National Library of Ireland, University College, Dublin and the Public Library of Belfast, and another set in the Public Library in New York.

In the 1930s he undertook further historical work when he was commissioned by the government to write a series of county histories of the Irish language for schools; five of the ten parts were published in his lifetime.

President of Sinn Féin

O'Flanagan was elected president of Sinn Féin in October 1933 and held that position until 1935. Brian O'Higgins resigned from the party in protest at O'Flanagan's presidency.[67] For his presidential address at the annual Sinn Féin Ard-Fheis on 14 October 1934, O'Flanagan gave a speech titled "The Strength of Sinn Féin," where he traced the evolution of the party through several incarnations and splits from his unique perspective.

The two vice-presidents elected were the two men of opposite views who formed the nucleus of the provisional committee. The two secretaries elected were Austin Stack and Darell Figgis. The two treasurers were Laurence Ginnell and William Cosgrave. The highest votes for membership of the standing committee were given to John MacNeill and Cathal Brugha.

When the so-called treaty came, one of the original vice-presidents of the organization became its foremost champion. The other remained on the side of the Republic. One of the secretaries became an eloquent spokesman of the Free State cause, the other fought against it to his last breath.

One of the treasurers became for many years the leader of the Free State majority party. The other died in harness in the ranks of the Republic. Of the two who came first in the list for the Standing Committee, the name of one will go down into Irish history as the outstanding hero martyr of the Republican cause; that of the other as the leading intellectual champion of the policy of compromise. We only had one president. The president found it impossible to divide himself in two. [91]

O'Flanagan was an active member of the National Graves Association, and in 1935 he unveiled the Moore's Bridge memorial in Kildare in memory of seven republican volunteers executed by the Free State in December 1922.[92]

Spanish Civil War

Sinn Féin party lacked energy and vision in the mid 1930s. The 1935 Árd Fhéis of Sinn Féin, held in Wynn's Hotel, Dublin, was chaired by O'Flanagan, back after a recent illness. In his address he "stated that Sinn Féin would have contested the recent Galway by-election had they had a candidate of personality. "Sceilg," Count Plunkett and Tom Maguire had each been asked but had refused."[81]

"In a statement on the Sunday resumption, Father O'Flanagan expressed the opinion that behind the war in Abyssinia lay the threat of Italy breaking Britain's hold upon the Mediterranean."[81]

When the Spanish Civil War broke out on 18 July 1936, O'Flanagan was one of the only Irish Catholic priests to defend the Spanish Republic.[3]

In Ireland the issue was presented in stark contrasts. Intermediate shades received little toleration. The Catholic church, arguably coming to the height of its conservatism, portrayed the war as a struggle between Christ and anti-Christ. Religion was under attack. Christian civilisation was mortally imperilled by the poison of communism. Innumerable sermons dinned home the dubious tenet that whatever opposed the onrush of communism was good. A joint pastoral of the Irish bishops firmly supported Franco.[6]