Magnitsky legislation

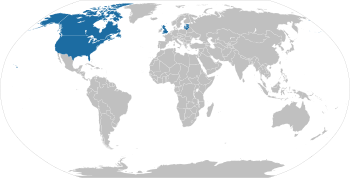

Magnitsky legislation refers to laws providing for governmental sanctions against foreign individuals who have committed human rights abuses or been involved in significant corruption. They originated with the United States which passed the first Magnitsky legislation in 2012, following the death of Sergei Magnitsky in Russia in 2009. Since then, a number of countries have passed similar legislation including Russia, Canada and the United Kingdom.

Origins

In 2008, Sergei Magnitsky, a tax accountant accused Russian tax officials and law enforcement of stealing $230 million in tax rebates from Hermitage Capital.[1] He, in turn, was accused of aiding tax evasion, arrested and jailed.[2] He was allededly beaten by police,[1] and died in Matrosskaya Tishina detention facility in November 2009.[3] In 2012, the United States Congress passed the Magnitsky Act, which imposed sanctions on the officials involved.[4]

Magnitsky legislation by country

Magnitsky legislation has been enacted in a number of countries, including the United States, United Kingdom, Russia, Estonia, Canada, Lithuania, Latvia, Gibraltar, Jersey and Kosovo.[5]

Canada

Canada passed its own Magnitsky legislation in October 2017 as the Justice for Victims of Corrupt Foreign Officials Act,[6][7] despite earlier warnings from the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs that the law would be a "blatantly unfriendly step", and further damage relations with Russia.[8][9] However, Russia had already placed Canada's Foreign Minister, Chrystia Freeland, and twelve other Canadian politicians and activists on a Kremlin 'blacklist' and had disallowed them from entry into "Russia because of their criticism of Russian actions in Ukraine and its annexation of Crimea", under the equivalent Russian law.[8]

Russian president Vladimir Putin, accused Canada of "political games" over its new Magnitsky law.[10]

Canada's government subsequently targeted sanctions against nineteen Venezuelan and three South Sudanese officials, along with thirty Russian individuals.[11]

Estonia

On 8 December 2016, Estonia introduced a new law that disallowed foreigners convicted of human rights abuses from entering Estonia. The law, which was passed unanimously in the Estonian Parliament, states that it entitles Estonia to disallow entry to people if, among other things, "there is information or good reason to believe" that they took part in activities which resulted in the "death or serious damage to health of a person".[12]

Gibraltar

In March 2018, Gibraltar passed Magnitsky legislation.[13]

Jersey

Jersey passed Magnitsky legislation as its "Sanctions and Asset Freezing (Jersey) Law" (SAFL) in December 2018.[14] The new law reincorporated the effects of the previous "Terrorist Asset-Freezing (Jersey) Law 2011" (TAFL) and the "United Nations Financial Sanctions (Jersey) Law 2017" (UNFSL) which it repealed. The SAFL went into effect on 19 July 2019.[15]

Kosovo

On 29 January 2020, Kosovo passed Magnitsky legislation.[16] This was announced by foreign minister Behgjet Pacolli on Twitter.[17]

Lithuania

On 16 November 2017 (the 8th anniversary of Sergei Magnitsky's death), the Parliament of Lithuania unanimously passed their version of Magnitsky legislation.[18]

Latvia

On 8 February 2018, the Parliament of Latvia (Saeima) accepted attachment of a law of sanctions, inspired by the Sergei Magnitsky case, to ban foreigners deemed guilty of human rights abuses from entering the country.[19]

United Kingdom

On 21 February 2017 the UK House of Commons unanimously passed an amendment to the country's Criminal Finances Bill inspired by the Magnitsky Act that would allow the government to freeze the assets of international human rights violators in the UK.[20][21]

On 1 May 2018, the UK House of Commons, without opposition, added the "Magnitsky amendment" to the Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Bill that would allow the British government to impose sanctions on people who commit gross human rights violations.[21][22]

United States

The original Magnitsky Act of 2012 was expanded in 2016 into a more general law authorizing the US government to sanction those found to be human rights offenders or those involved in significant corruption, to freeze their assets, and to ban them from entering the U.S.[23]

Legislation passed by Russia in response

In 2012, the Russian government responded to the new US Magnitsky Act[24] by passing the Dima Yakovlev Law[25] banning Americans from adopting Russian children, and providing for sanctions against U.S. citizens involved in violations of the human rights and freedoms of Russian citizens.[26][27]

Pending legislation

Magnitsky legislation is under consideration in a number of countries.

Australia

MP Michael Danby introduced a Magnitsky bill in the Australian parliament in December 2018,[28] but the bill died when the session ended.[29]

European Union

EU Parliament passed a resolution in March 2019 to urge EU and 28 member states to legislate similar with Magnitsky Act.[30][31][32][33]

On 9 December 2019, Josep Borrell, the European Union's High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy (HR/VP), the chief co-ordinator and representative of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) within the EU, announced that all member states had "… agreed to launch the preparatory work for a global sanctions regime to address serious human rights violations, which will be the European Union equivalent of the so-called Magnitsky Act of the United States."[34][35]

Moldova

In July 2018, a Magnitsky bill was introduced into the Moldova parliament.[36] It mandated sanctions against individuals who "have committed or contributed to human rights violations and particularly serious acts of corruption that are harmful to international political and economic stability."[37] As of January 2020 it had not been acted upon;[37][38] however, the DA Platform party is still pushing for its adoption, although the ACUM coalition has dropped its demand for passage.[38]

Ukraine

In December 2017, there was a Magnitsky bill introduced into the Ukrainian parliament.[39] The bill would have given authority to sanction foreign individuals who grossly violate human rights through the use of visa bans, asset freezes, and restrictions on asset transfer.[37] However the bill was quickly tabled, and in September 2018 it was removed from the legislative agenda.[37]

Notes and references

- "Q&A: The Magnitsky affair". BBC News. 11 July 2013.

- Aldrick, Philip (19 November 2009). "Russia refuses autopsy for anti-corruption lawyer". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 22 November 2009.

- "Criminal Case Against Magnitsky Doctor Closed". Sputnik News. 9 April 2012. Archived from the original on 16 September 2017.

Prison officials said he died due to heart failure and toxic shock.

- Palmer, Doug (14 December 2012). "Obama signs trade, human rights bill that angers Moscow". The Daily Star. Lebanon. Reuters. Archived from the original on 14 December 2012.

- Ochab, Ewelina U. (17 May 2020). "On Targeted Sanctions To Address Attacks Against Journalists And Media Freedom Violations". Forbes. Archived from the original on 17 March 2020.

- "Canada Passes Version Of Magnitsky Act, Raising Moscow's Ire". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 19 October 2017. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017.

- Zaman, Kashif (9 November 2017). "Canada enacts Justice for Victims of Corrupt Foreign Officials Act - Implications for compliance with Canadian anti-money laundering requirements". sler Hoskin & Harcourt LLP. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020.

- Sevunts, Levon (18 May 2017). "Russia warns Canada over 'blatantly unfriendly' Magnitsky Act". CBC News. Archived from the original on 2 June 2017.

- "As Canada's Magnitsky bill nears final vote, Russia threatens retaliation". CBC News. Thomson Reuters. 4 October 2017. Archived from the original on 25 October 2017.

- Blanchfield, Mike (20 October 2017). "Vladimir Putin accuses Canada of 'political games' over Magnitsky law". Global News. The Canadian Press. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017.

- "Russia, South Sudan and Venezuela are Canada's 1st targets using sanctions under Magnitsky Act". CBC News. 3 November 2017. Archived from the original on 3 November 2017.

- Rettman, Andrew (9 December 2016). "Estonia joins US in passing Magnitsky law". EUobserver. Archived from the original on 10 December 2016.

- Graham, Chris (11 March 2018). "The Magnitsky Act: How a lawyer's death spurred a global fight against Russian corruption and abuses". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 15 March 2020.

Last week Gibraltar became the latest country to pass the law ...

- Byrne, Rob (6 December 2018). "Putin critic welcomes "dirty"money law". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020.

- "Sanctions and asset-freezing law". The Jersey Financial Services Commission (JFSC). July 2019. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020.

- Bami, Xhorxhina (29 January 2020). "Outgoing Kosovo Govt Adopts Magnitsky Act". Balkan Insight. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020.

- Pacolli, Behgjet (29 January 2020). "I'm proud that today the government of #Kosovo established the Kosovo #Magnitsky Act sanction foreign government officials implicated in human rights abuses anywhere in the world in line w/@StateDept practice. #Kosovo takes strategic step align its foreign policy w/United States". Twitter. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- "Lithuania: Parliament Adopts Version of Magnitsky Act". Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. 16 November 2017. Archived from the original on 11 July 2018.

- "Latvia Becomes Final Baltic State to Pass Magnitsky Law". Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. 9 February 2018. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- "UK House of Commons Passes the Magnitsky Asset Freezing Sanctions". Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. 21 February 2017. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017.

- Smith, Ben; Dawson, Joanna (27 July 2018). "Magnitsky legislation" (PDF). House of Commons.

- "UK lawmakers back 'Magnitsky amendment' on sanctions for human rights abuses". Reuters. 1 May 2018. Archived from the original on 29 January 2019.

- The Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act "The US Global Magnitsky Act: Questions and Answers". Human Rights Watch. 13 September 2017. Archived from the original on 28 September 2017.

- Englund, Will (11 December 2012). "Russians say they'll name their Magnitsky-retaliation law after baby who died in a hot car in Va". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 12 December 2012.

- "On Sanctions for Individuals Violating Fundamental Human Rights and Freedoms of the Citizens of the Russian Federation"

- "A law on sanctions for individuals violating fundamental human rights and freedoms of Russian citizens has been signed". Office of the President of Russia. 28 December 2012. Archived from the original on 2 January 2013.

- MacFarquhar, Neil; Kramer, Andrew E. (12 July 2017). "Natalia Veselnitskaya, Lawyer Who Met Trump Jr., Seen as Fearsome Moscow Insider". The New York Times. p. A1. Archived from the original on 12 July 2017.

- "International Human Rights and Corruption (Magnitsky Sanctions) Bill 2018". Parliament of Australia. December 2018. Archived from the original on 20 January 2019.

- Gredley, Rebecca (30 March 2020). "Australia Is Considering Introducing Human Rights Sanctions Regime". NTD News. Australian Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020.

The government says it already has a sanctions regime as well as character tests for visas.

- Rikard Jozwiak (26 April 2018). "MEPs Urge EU Magnitsky Act To Tackle Kremlin's 'Antidemocratic' Activities". Radio Free Europe. Archived from the original on 26 May 2018.

- "European Parliament resolution on a European human rights violations sanctions regime". EU Parliament. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- "MEPs call for EU Magnitsky Act to impose sanctions on human rights abusers". EU Parliament. 14 March 2019.

- Rikard Jozwiak (14 March 2019). "European Parliament Urges EU To Adopt Legislation Like Magnitsky Act". Radio Free Europe.

- "The Magnitsky Act Comes to the EU: A Human Rights Sanctions Regime Proposed by the Netherlands". Netherlands Helsinki Committee. December 2019. Archived from the original on 4 February 2020.

- "EU ministers break ground on European 'Magnitsky Act'". euractiv.com. 10 December 2019.

- Cappello, John (21 November 2018). "Moldova Considers Adopting the Global Magnitsky Act". Real Clear Defense. RealClear Media Group. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020.

- Shagina, Maria (26 April 2019). "Magnitsky-style sanctions in the Eastern Partnership". The European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR).

- "DA platform suggests adopting analog to Magnitsky law in Moldova". Infotag. 21 January 2020. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020.

- "Magnitsky Act has been introduced into Verkhovna Rada (Ukrainian parliament)". Samopomich (Самопоміч). 18 December 2017. Archived from the original on 31 December 2017.