Machine Gun Kelly

George Kelly Barnes (July 18, 1895 – July 18, 1954),[1] better known by his nickname "Machine Gun Kelly", was an American gangster from Memphis, Tennessee, during the prohibition era. His nickname came from his favorite weapon, a Thompson submachine gun. He is best known for the kidnapping of the oil tycoon and businessman Charles F. Urschel in July 1933, from which he and his gang collected a $200,000 ransom (around $4 million dollars as of today.).[2] Urschel had collected and left considerable evidence that assisted the subsequent FBI investigation, which eventually led to Kelly's arrest in Memphis, Tennessee, on September 26, 1933.[1] His crimes also included bootlegging and armed robbery.

Machine Gun Kelly | |

|---|---|

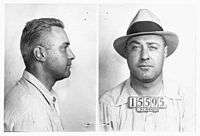

Mugshot of Barnes | |

| Born | George Kelly Barnes July 18, 1895 |

| Died | July 18, 1954 (aged 59) |

| Other names | Machine Gun Kelly, Pop Gun Kelly |

| Occupation | Gangster, bootlegger and businessman |

Career

During the Prohibition era of the 1920s and 1930s, Kelly worked as a bootlegger for himself as well as a colleague.[3] After a short time, and several run-ins with the local Memphis police, he decided to leave town and head west with his girlfriend. To protect his family and to escape law enforcement officers, he changed his name to George R. Kelly.[4] He continued to commit smaller crimes and bootlegging. He was arrested in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1928, for smuggling liquor onto an Indian Reservation, and sentenced to three years at Leavenworth Penitentiary, Kansas, beginning February 11, 1928. He was reportedly a model inmate and was released early. Shortly thereafter, Kelly married Kathryn Thorne, an experienced criminal who purchased Kelly's first machine gun and insisted – despite his lack of interest in weapons – on his performing target practice in the countryside, and went to great lengths to familiarize his name within underground crime circles.[5]

Kelly's last criminal activity – the July 1933 kidnapping of wealthy Oklahoma City resident, Charles F. Urschel and his friend Walter R. Jarrett – would become his undoing. The Kellys demanded a ransom of $200,000 ($4 million today), and held Urschel at the farm of Kathryn's mother and step-father.[6] Urschel, having been blindfolded, made note of evidence of his experience, including remembering background sounds, counting footsteps and leaving fingerprints on surfaces in reach. This proved invaluable for the FBI in its investigation, as agents concluded that Urschel had been held in Paradise, Texas, based on sounds that Urschel remembered hearing while he was being held hostage.

An investigation conducted in Memphis disclosed that the Kellys were living at the residence of J. C. Tichenor. Special agents from Birmingham, Alabama, were immediately dispatched to Memphis, where, in the early morning hours of September 26, 1933, a raid was conducted. George Kelly and Kathryn Thorne were taken into custody by FBI agents and Memphis police. It is often reported that Kelly was caught without a weapon and allegedly shouted, "Don't shoot, G-Men! Don't shoot, G-Men!" as he surrendered to FBI agents. This version of events appears to be a media myth created months after the arrest. Another version of the raid alleged Kelly had a pistol in his hand, but with a shotgun aimed at his heart he surrendered mumbling something along the lines of "I've been expecting you." However, the FBI's earliest account of the event was written between three and five days after Kelly’s arrest and states: "Agent Rorer saw that Kelly…had proceeded into the front bedroom and was in a corner with his hands raised. He was covered by [Memphis Police] Sergeant [name withheld]." with Kelly not reported to have spoken at all.[7][8][9]

The arrest of the Kellys was overshadowed by the escape of ten inmates, including all of the members of the future Dillinger gang, from the penitentiary in Michigan City, Indiana, that same night.[10]

On October 12, 1933, George Kelly and Kathryn Thorne were convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment. The trial was held at the Post Office, Courthouse, and Federal Office Building in Oklahoma City.

An investigation in Coleman, Texas, disclosed that the Kellys had been housed and protected by Cassey Earl Coleman and Will Casey, and that Coleman had assisted George Kelly in storing $73,250 of the Urschel ransom money on his ranch. This money was located by Bureau agents in the early morning hours of September 27 in a cotton patch on Coleman's ranch. They were both indicted in Dallas, Texas, on October 4, 1933, charged with harboring a fugitive and conspiracy, and on October 17, 1933, Coleman, after entering a plea of guilty, was sentenced to serve one year and one day, and Casey, after trial and conviction, was sentenced to serve two years in the United States Penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kansas.[11]

The kidnapping of Urschel and the two trials that resulted were historic in several ways. They were:

- the first federal criminal trials in the United States in which film cameras were allowed;

- the first kidnapping trials after the passage of the Lindbergh Law, which made kidnapping a federal crime;

- the first major case solved by J. Edgar Hoover's FBI; and

- the first prosecution in which defendants were transported by airplane.

Death

Machine Gun Kelly spent his remaining 21 years in prison. During his time at Alcatraz, he got the nickname "Pop Gun Kelly". According to fellow inmate Dale Stamphill the nickname originated because, "He told big fish stories. The cons called him ‘Pop Gun Kelly’ after cork guns that were popular with kids...the guys didn’t take him seriously...." This may have stemmed from the fact that, in addition to his exaggerated tall tales, Kelly was a model prisoner and did not act like the brutal gangster his wife, the media, and FBI had made him out to be.[12][13][14][15] He spent 17 years on Alcatraz as inmate number 117, working in the prison industries, continuing to boast and exaggerate his past escapades to other inmates, and was quietly transferred back to Leavenworth in 1951. He died of a heart attack at Leavenworth on July 18, 1954, his 59th birthday, and was buried at Cottondale Texas Cemetery in Kathryn Kelly's stepfather's family plot[16][17] with a small headstone marked "George B. Kelley 1954".[18] Kathryn Kelly was released from prison in 1958 and lived in relative anonymity in Oklahoma under the assumed name "Lera Cleo Kelly" until her death in 1985 at the age of 81.[19]

In popular culture

Machine Gun Kelly and his crimes are portrayed in films such as Machine-Gun Kelly (1958), The FBI Story (1959) and Melvin Purvis: G-Man (1974).

Crime novelist Ace Atkins' 2010 book Infamous is based on the Urschel kidnapping and George Kelly and Kathryn Thorne. Kelly is (along with Pretty Boy Floyd and Baby Face Nelson) one of the main characters of the comic book series Pretty, Baby, Machine.

George Kelly and Kathryn Thorne were the inspiration for "Machine Gun Kelly" (1970), a song written by Danny "Kootch" Kortchmar and recorded by James Taylor on his 1971 album Mud Slide Slim and the Blue Horizon.

Machine Gun Kelly is the stage name for American musician/actor Colson Baker, from Cleveland, Ohio.

Kelly was an inspiration to the popular UK punk band, The Angelic Upstarts, for their track “Machine Gun Kelly” written by Thomas ‘Mensi’ Mensforth.

References

- "George 'Machine Gun' Kelly". Alcatraz History.com. 2015. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- O'Dell, Larry. "Urschel Kidnapping". Oklahoma Historical Society. Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Archived from the original on December 28, 2014. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- Finger, Michael (September 7, 2005). "Public Enemy Number One: The real story of Machine Gun Kelly, the Memphis boy who grew up to become the most wanted man in America". Memphis Flyer.

- "Machine Gun Kelly". Family Tree Genealogy. Retrieved July 13, 2009.

- 200 Texas Outlaws and Lawmen, 1835-1935, Laurence J. Yadon, Dan Anderson, ed. Robert Barr Smith, Pelican Publishing Company, 2008, p. 144

- "Kathryn Kelly – Crime Museum". Crime Museum. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- "FBI 100 - Machine Gun Kelly". FBI.

- Finger, Michael. "Public Enemy Number One". Memphis Flyer.

- ""Machine Gun" Kelly and the Legend of the G-Men". FBI.

- Fee, Christopher R.; Webb, Jeffrey B. (31 August 2016). American Myths, Legends, and Tall Tales: An Encyclopedia of American Folklore (3 Volumes). ABC-CLIO. p. 310. ISBN 978-1-61069-568-8.

- "FBI 100. The legend of 'Machine Gun Kelly'". FBI. September 26, 2008. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- "Machine Gun Kelly and His Lost Years on Alcatraz". July 16, 2019.

- "Machine Gun Kelly captured in Memphis". historic-memphis.com.

- "George "Machine Gun" Kelly". www.alcatrazhistory.com.

- Finger, Michael (July 10, 2017). "The Real Story of Machine Gun Kelly". Memphis magazine.

- The Paradise Historical Society, Machine Gun Kelly URL= http://www.paradisehistoricalsociety.org/machine-gun-kelly Date accessed= 18 October 2018

- "Machinegun' Kelly's Wife Lost Chance for Freedom Thwarted Deal Sealed Convictions | News OK". February 18, 2017. Archived from the original on February 18, 2017. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- "George "Machine Gun" Kelly". Wise County Sheriff's Department. 2003. Archived from the original on September 27, 2006. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- "Kathryn Kelly".

Further reading

- Atkins, Ace (2010). Infamous. G.P. Putnam's Sons.

- Hamilton, Stanley (2003). Machine Gun Kelly's Last Stand. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1247-5.

- Kirkpatrick, E.E. (1934). Crimes' Paradise (1st ed.). San Antonio, Texas: The Naylor Company.

- Urschel, Joe (2016). The Year of Fear:Machine Gun Kelly and the Manhunt That Changed the Nation. Minotaur Books. ISBN 978-1-250-10548-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Machine Gun Kelly. |