Louis Till

Louis Till (February 7, 1922 – July 2, 1945) was an American soldier. He was the father of Emmett Till, whose murder in August 1955 at the age of 14 galvanized the Civil Rights Movement. A soldier during World War II, Louis Till was executed by the U.S. Army in 1945 after being found guilty of murder and rape. The circumstances of his death were little known even to his family until they were revealed after the trial of his son's murderers ten years later, which affected subsequent discourse on the death of Emmett Till.

Louis Till | |

|---|---|

| Born | February 7, 1922 New Madrid, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | July 2, 1945 (aged 23) Pisa, Italy |

| Cause of death | Capital punishment |

| Resting place | Oise-Aisne American Cemetery (near) Fère-en-Tardenois, France |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Argo Community High School |

| Years active | 1943–1945 |

| Known for | Father of Emmett Till |

| Spouse(s) | |

Life

Louis Till grew up an orphan in New Madrid, Missouri.[1] As a young man he worked at the Argo Corn Company and was an amateur boxer. At the age of 17, Till began courting Mamie Carthan, a woman of the same age. Her parents disapproved, thinking the charismatic Till was "too sophisticated" for their daughter. At her mother's insistence Mamie broke off their courtship but the persistent Till won out, and they married on October 14, 1940. Both were 18 years old.[2] Their only child, Emmett Louis Till, was born on July 25, 1941. Mamie left her husband soon after learning that he had been unfaithful. Louis, enraged, choked her to unconsciousness, to which she responded by throwing scalding water at him. Eventually Mamie obtained a restraining order against him. After he repeatedly violated this order, a judge forced Till to choose between enlistment in the Army and imprisonment. Choosing the former, he enlisted in 1943.[3]

Crime and death

While serving in the Italian Campaign, Till was arrested by military police, who suspected him and another soldier, Fred A. McMurray, of the murder of an Italian woman and the rape of two others, in Civitavecchia. After a short investigation, he and McMurray were court-martialed, found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging. The sentence was carried out at the United States Army Disciplinary Training Center north of Pisa on July 2, 1945.[4][5] He had been imprisoned alongside American poet Ezra Pound, who had been imprisoned for collaborating with the Nazis and Italian Fascists; he is mentioned in lines 171-173 of Canto 74 of Pound's Pisan Cantos:[6]

- Till was hung yesterday

- for murder and rape with trimmings

Till was buried in Grave 73, Row 4 of Plot E in Oise-Aisne American Cemetery.[7]

Aftermath

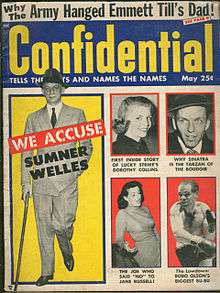

The circumstances of Till's death were not revealed to his family; Mamie Till was only told that her husband's death was due to "willful misconduct". Her attempts to learn more were comprehensively blocked by the United States Army bureaucracy.[5] The full details of Louis Till's crimes and execution only emerged ten years later. On August 28, 1955, 14-year-old Emmett Till was murdered in Mississippi, after reportedly trying to flirt with Carolyn Bryant, a local white woman (years later Bryant disclosed that at the time she had fabricated testimony that Till made verbal or physical advances towards her in the store.[8]). Her husband and brother-in-law abducted Till and beat him to death, then threw his body into the river. Both were arrested, charged with and tried for first-degree murder, but were acquitted by an all-white jury. After the trial gained international media attention, Mississippi senators James Eastland and John C. Stennis uncovered details about Louis Till's crimes and execution and released them to reporters.[5]

The Southern media immediately leapt upon the story: various editorials claimed that the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the "Yankee" media had covered up, or lied about, the record of Emmett Till's father.[9] Many of these editorials specifically attacked a short piece that had appeared in Life magazine, which presented Louis Till as having died fighting for his country in France. This article was in fact the only published piece that ever lionized Pvt. Till; in response, Life quickly published a retraction.[9] For white Southerners, however, the impression was left that the erroneous Life article was representative of the Northern media in general.[9] Subsequently, other editorials went so far as to tar Emmett Till with his father's crimes. These essentially portrayed Emmett as a serial rapist after the fashion of his father, thereby justifying his murder.[10]

In October 1955, one month after Emmett Till's abductors and murderers had been acquitted of the murder, the fate ten years earlier of Louis Till was made public for all to know (even though his military record had been confidential). The effect was to smear the reputation of young dead Emmett by associating him with the crimes for which his father had been executed. In November 1955, one month later, a grand jury declined to indict the two abductors for kidnapping Till, despite the testimony given that they had in fact admitted kidnapping him.

In 2016, 71 years after the execution of Louis Till and 61 years after the murder of his son Emmett, author John Edgar Wideman explored the circumstances leading up to and including the military conviction of Louis Till. In the book, Writing to Save a Life – The Louis Till File, Wideman examined the trial record from the US military United States v. Louis Till (CMZ288642).[11] Upon his request it had been sent to him by the United States Court of Criminal Appeals, Arlington, Virginia. This trial record was more than 200 pages long. In his review of the trial record, Wideman concluded that there may indeed be questions to be raised of conclusions reached about Louis Till's criminal conduct, drawn in and from the transcript. In 2016 Wideman stated that he could not "rescue Louis Till from prison and the hangman".[12]

See also

Notes

- Till-Mobley and Benson, pp. 14–15.

- "American Experience . The Murder of Emmett Till . People & Events". Pbs.org. Retrieved 2017-01-05.

- Till-Mobley and Benson, pp. 14–17.

- Houck and Grindy, pp. 134–135.

- Whitfield, p. 117.

- Pound, Ezra (1948). The Pisan Cantos. New York: New Directions. ISBN 978-0-8112-1558-9.

- "Millions of Cemetery Records and Online Memorials". Find A Grave. Retrieved 2017-01-05.

- Pérez-Peña, Richard (2017-01-27). "Woman Linked to 1955 Emmett Till Murder Tells Historian Her Claims Were False". The New York Times.

- Houck and Grindy, p. 136.

- Houck and Grindy, p. 138.

- Wideman, John Edgar. Writing to Save a Life. p. 88.

- Wideman, John Edgar. Writing to Save a Life. p. 163.

References

- Houck, Davis; Grindy, Matthew (2008). Emmett Till and the Mississippi Press, University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 1-934110-15-9

- Till-Mobley, Mamie; Benson, Christopher (2003). The Death of Innocence: The Story of the Hate Crime That Changed America, Random House. ISBN 1-4000-6117-2

- Whitfield, Stephen (1991). A Death in the Delta: The Story of Emmett Till, JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-4326-6

- Wideman, John Edgar (2016). Writing to Save a Life - The Louis Till File. New York, NY: Scribner. ISBN 978-1-5011-4728-9