Lord Howe Island

Lord Howe Island (/haʊ/; formerly Lord Howe's Island) is an irregularly crescent-shaped volcanic remnant in the Tasman Sea between Australia and New Zealand, 600 km (320 nmi) directly east of mainland Port Macquarie, 780 km (420 nmi) northeast of Sydney, and about 900 km (490 nmi) southwest of Norfolk Island. It is about 10 km (6.2 mi) long and between 0.3 and 2.0 km (0.19 and 1.24 mi) wide with an area of 14.55 km2 (3,600 acres), though just 3.98 km2 (980 acres) of that comprise the low-lying developed part of the island.[5]

Satellite image of the island; north is up | |

| |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Lord Howe Island Group, Tasman Sea |

| Coordinates | 31°33′15″S 159°05′06″E |

| Total islands | 28 |

| Major islands | Lord Howe Island, Admiralty Group, Mutton Bird Islands, and Balls Pyramid |

| Area | 14.55 km2 (5.62 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 875 m (2,871 ft) |

| Highest point | Mount Gower |

| Administration | |

| Administrative Division | Unincorporated area of New South Wales Self-governed by the Lord Howe Island Board[1] Part of the electoral district of Port Macquarie[2] Part of the Division of Sydney[3] |

| Demographics | |

| Population |

|

| Pop. density | 26.25/km2 (67.99/sq mi) |

| Additional information | |

| Time zone | |

| • Summer (DST) | |

| Official name | Lord Howe Island Group |

| Type | Natural |

| Criteria | vii, x |

| Designated | 1982 (6th session) |

| Reference no. | 186 |

| State Party | Australia |

| Region | Asia-Pacific |

Australian National Heritage List | |

| Official name | Lord Howe Island Group, Lord Howe Island, NSW, Australia |

| Type | Natural |

| Designated | 21 May 2007 |

| Reference no. | 105694 |

| File number | 1/00/373/0001 |

| Official name | Lord Howe Island Group |

| Type | State heritage (landscape) |

| Designated | 2 April 1999 |

| Reference no. | 970 |

| Type | Other - Landscape - Cultural |

| Category | Landscape - Cultural |

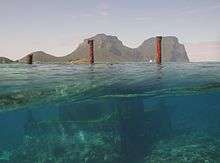

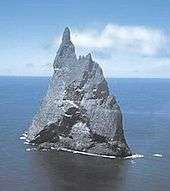

Along the west coast is a sandy semi-enclosed sheltered coral reef lagoon. Most of the population lives in the north, while the south is dominated by forested hills rising to the highest point on the island, Mount Gower (875 m, 2,871 ft).[6] The Lord Howe Island Group[6] comprises 28 islands, islets, and rocks. Apart from Lord Howe Island itself, the most notable of these is the volcanic and uninhabited Ball's Pyramid about 23 km (14 mi; 12 nmi) to the southeast of Howe. To the North lies a cluster of seven small uninhabited islands called the Admiralty Group.[7]

The first reported sighting of Lord Howe Island took place on 17 February 1788, when Lieutenant Henry Lidgbird Ball, commander of the Armed Tender HMS Supply, was en route from Botany Bay to found a penal settlement on Norfolk Island.[8] On the return journey, Ball sent a party ashore on Lord Howe Island to claim it as a British possession.[9] It subsequently became a provisioning port for the whaling industry,[10] and was permanently settled in June 1834.[11] When whaling declined, the 1880s saw the beginning of the worldwide export of the endemic kentia palms,[12] which remains a key component of the Island's economy. The other continuing industry, tourism, began after World War II ended in 1945.

The Lord Howe Island Group is part of the state of New South Wales[13] and is regarded legally as an unincorporated area administered by the Lord Howe Island Board,[13] which reports to the New South Wales Minister for Environment and Heritage.[13] The island's standard time zone is UTC+10:30, or UTC+11 when daylight saving time applies.[14] The currency is the Australian dollar. Commuter airlines provide flights to Sydney, Brisbane, and Port Macquarie.

UNESCO records the Lord Howe Island Group as a World Heritage Site of global natural significance.[15] Most of the island is virtually untouched forest, with many of the plants and animals found nowhere else in the world. Other natural attractions include the diversity of the landscapes, the variety of upper mantle and oceanic basalts, the world's southernmost barrier coral reef, nesting seabirds, and the rich historical and cultural heritage.[16] The Lord Howe Island Act 1981 established a "Permanent Park Preserve" (covering about 70% of the island).[14] The island was added to the Australian National Heritage List on 21 May 2007[17] and the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.[18] The surrounding waters are a protected region designated the Lord Howe Island Marine Park.[19]

Bioregion

Lord Howe Island is part of the IBRA region Pacific Subtropical Islands (code PSI) and is subregion PSI01 with an area of 1,909 ha (4,720 acres).[20]

History

1788–1834: First European visits

Prior to European discovery and settlement, Lord Howe Island apparently was uninhabited, and unknown to Polynesian peoples of the South Pacific.[21] The first reported European sighting of Lord Howe Island was on 17 February 1788 by Lieutenant Henry Lidgbird Ball, commander of the Armed Tender HMS Supply (the oldest and smallest of the First Fleet ships), which was on its way from Botany Bay with a cargo of nine male and six female convicts to found a penal settlement on Norfolk Island.[8] On the return journey of 13 March 1788, Ball observed Ball's Pyramid and sent a party ashore on Lord Howe Island to claim it as a British possession.[9] Numerous turtles and tame birds were captured and returned to Sydney.[22] Ball named Mount Lidgbird and Ball's Pyramid after himself and the main island after Richard Howe, 1st Earl Howe, who was First Lord of the Admiralty at the time.[9]

Many names on the island date from this time, and also from May of the same year, when four ships of the First Fleet, HMS Supply, Charlotte, Lady Penrhyn and Scarborough, visited it. Much of the plant and animal life was first recorded in the journals and diaries of visitors such as David Blackburn, Master of Supply, and Arthur Bowes Smyth,[23] surgeon of the Lady Penrhyn.

Smyth was in Sydney when the Supply returned from the first voyage to Norfolk Island. His journal entry for 19 March 1788 noted that "the Supply, in her return, landed at the island she [discovered] in going out, and all were very agreeably surprised to find great numbers of fine turtle on the beach and, on the land amongst the trees, great numbers of fowls very like a guinea hen, and another species of fowl not unlike the landrail in England, and all so perfectly tame that you could frequently take hold of them with your hands but could, at all times, knock down as many as you thought proper, with a short stick. Inside the reef also there were fish innumerable, which were so easily taken with a hook and line as to be able to catch a boat full in a short time. She brought thirteen large turtle to Port Jackson and many were distributed among the camp and fleet."[23]

Watercolour sketches of native birds including the Lord Howe woodhen (Gallirallus sylvestris), white gallinule (Porphyrio albus), and Lord Howe pigeon (Columba vitiensis godmanae), were made by artists including George Raper and John Hunter. As the latter two birds were soon hunted to extinction, these paintings are their only remaining pictorial record.[24][25] Over the next three years, the Supply returned to the island several times in search of turtles, and the island was also visited by ships of the Second and Third Fleets.[26] Between 1789 and 1791, the Pacific whale industry was born with British and American whaling ships chasing sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) along the equator to the Gilbert and Ellice archipelago, then south into Australian and New Zealand waters.[27] The American fleet numbered 675 ships and Lord Howe was located in a region known as the Middle Ground noted for sperm whales and southern right whales (Eubalaena australis).[28]

The island was subsequently visited by many government and whaling ships sailing between New South Wales and Norfolk Island and across the Pacific, including many from the American whaling fleet, so its reputation as a provisioning port preceded settlement,[10] with some ships leaving goats and pigs on the island as food for future visitors. Between July and October 1791, the Third Fleet ships arrived at Sydney and within days, the deckwork was being reconstructed for a future in the lucrative whaling industry. Whale oil was to become Australia's most profitable export until the 1830s, and the whaling industry shaped Lord Howe Island's early history.[29]

1834–1841: Settlement

Permanent settlement on Lord Howe was established in June 1834, when the British whaling barque Caroline, sailing from New Zealand and commanded by Captain John Blinkenthorpe, landed at what is now known as Blinky Beach. They left three men, George Ashdown, James Bishop, and Chapman, who were employed by a Sydney whaling firm to establish a supply station. The men were initially to provide meat by fishing and by raising pigs and goats from feral stock. They landed with (or acquired from a visiting ship) their Māori wives and two Māori boys. Huts were built in an area now known as Old Settlement, which had a supply of fresh water, and a garden was established west of Blinky Beach.[11][30]

This was a cashless society; the settlers bartered their stores of water, wood, vegetables, meat, fish, and bird feathers for clothes, tea, sugar, tools, tobacco, and other commodities not available on the island, but it was the whalers' valuation that had to be accepted.[31][32] These first settlers eventually left the island when they were bought out for £350 in September 1841 by businessmen Owen Poole and Richard Dawson (later joined by John Foulis), whose employees and others then settled on the island.[33]

1842–1860: Trading provisions

The new business was advertised and ships trading between Sydney and the New Hebrides (Vanuatu) would also put into the island. Rover's Bride, a small cutter, became the first regular trading vessel.[34] Between 1839 and 1859, five to 12 ships made landfall each year, occasionally closer to 20, with seven or eight at a time laying off the reef.[35] In 1842 and 1844, the first children were born on the island. Then in 1847, Poole, Dawson, and Foulis, bitter at failing to obtain a land lease from the New South Wales government, abandoned the settlement although three of their employees remained.[36] One family, the Andrews, after finding some onions on the beach in 1848, cultivated them as the "Lord Howe red onion", which was popular in the Southern Hemisphere for about 30 years until the crop was attacked by smut disease.[37]

In 1849, just 11 people were living on the island, but soon the island farms expanded.[37] In the 1850s, gold was discovered on mainland Australia, where crews would abandon their ships, preferring to dig for gold than to risk their lives at sea. As a consequence, many vessels avoided the mainland and Lord Howe Island experienced an increasing trade, which peaked between 1855 and 1857.[38] In 1851, about 16 people were living on the island.[11] Vegetable crops now included potatoes, carrots, maize, pumpkin, taro, watermelon, and even grapes, passionfruit, and coffee.[30] Between 1851 and 1853, several aborted proposals were made by the NSW government to establish a penal settlement on the island.[39]

From 1851 to 1854, Henry Denham captain of HMS Herald, which was on a scientific expedition to the southwest Pacific (1852–1856), completed the island's first hydrographic survey. On board were three Scottish biologists, William Milne (a gardener-botanist from the Edinburgh Botanic Garden), John MacGillivray (naturalist) who collected fish and plant specimens, and assistant surgeon and zoologist Denis Macdonald. Together, these men established much basic information on the geology, flora, and fauna of the island.[40]

Around 1853, a further three settlers arrived on the American whaling barque Belle, captained by Ichabod Handy.[41] George Campbell (who died in 1856) and Jack Brian (who left the island in 1854) arrived, and the third, Nathan Thompson, brought three women (called Botanga, Bogoroo, and a girl named Bogue) from the Gilbert Islands. When his first wife Botanga died, he then married Bogue. Thompson was the first resident to build a substantial house in the 1860s from mainland cedar washed up on the beach.[42] Most of the residents with island ancestors have blood relations or are connected by marriage to Thompson and his second wife Bogue.[43]

In 1855, the island was officially designated as part of New South Wales by the Constitution Act.[44]

1861–1890: Scientific expeditions

From the early 1860s, whaling declined rapidly with the increasing use of petroleum, the onset of the California gold rush, and the American Civil War—with unfortunate consequences for the island. To explore alternative means of income, Thompson, in 1867, purchased the Sylph, which was the first local vessel to trade with Sydney (mainly pigs and onions). It anchored in deep water at what is now Sylph's Hole off Old Settlement Beach, but was eventually tragically lost at sea in 1873, which added to the woes of the island at that time.[45]

In 1869, the island was visited by magistrate P. Cloete aboard the Thetis investigating a possible murder. He was accompanied by Charles Moore, director of the Botanic Gardens in Sydney, and his assistant William Carron, who forwarded plant specimens to Ferdinand Mueller at the botanic gardens in Melbourne, who by 1875, had catalogued and published 195 species.[46] Also on the ship was William Fitzgerald, a surveyor, and Mr Masters from the Australian Museum. Together, they surveyed the island with the findings published in 1870 when the population was listed as 35 people, their 13 houses built of split palm battens thatched on the roof and sides with palm leaves.[47] Around this time, a downturn of trade began with the demise of the whaling industry and sometimes six to 12 months passed without a vessel calling. With the provisions rotting in the storehouses, the older families lost interest in market gardening.[48]

From 1860 to 1872, 43 ships had collected provisions, but from 1873 to 1887, fewer than a dozen had done so.[38] This prompted some activity from the mainland. In 1876, a government report on the island was submitted by surveyor William Fitzgerald based on a visit in the same year. He suggested that coffee be grown, but the kentia palm was already catching world attention.[12] In 1878, the island was declared a forest reserve and Captain Richard Armstrong became the first resident government administrator. He encouraged schools, tree-planting, and the palm trade, dynamited the north passage to the lagoon, and built roads. He also managed to upset the residents, and parliamentarian John Wilson was sent from the mainland in April 1882 to investigate the situation.[49] With Wilson was a team of scientists who included H. Wilkinson from the Mines Department, W. Condor from the Survey Department, J. Duff from the Sydney Botanical Gardens, and A. Morton from the Australian Museum. J. Sharkey from the Government Printing Office took the earliest known photographs of the island and its residents. A full account of the island appeared in the report from this visit,[50] which recommended that Armstrong be replaced. Meanwhile, the population had increased considerably and included 29 children; the report recommended that a schoolmaster be appointed.[51] This study sealed a lasting relationship with three scientific organisations, the Australian Museum, Sydney Royal Botanic Gardens, and Kew Royal Botanic Gardens.

1890–1999

In 1883, the company Burns Philp started a regular shipping service and the number of tourists gradually increased. By 1932, with the regular tourist run of SS Morinda, tourism became the second-largest source of external income after palm sales to Europe.[11] Morinda was replaced by Makambo in 1932, and she in turn by other vessels. The service continues into the present day with the fortnightly Island Trader service from Port Macquarie.[52]

The palm trade began in the 1880s when the lowland kentia palm (Howea forsteriana) was first exported to Britain, Europe, and America, but the trade was only placed on a firm financial footing when the Lord Howe Island Kentia Palm Nursery was formed in 1906 (see below).

The first plane to appear on the island was in 1931, when Francis Chichester alighted on the lagoon in a de Havilland Gipsy Moth converted into a floatplane. It was damaged there in an overnight storm, but repaired with the assistance of islanders and then took off successfully nine weeks later for a flight to Sydney.[53] After World War II, in 1947, tourists arrived on Catalina and then four-engined Sandringham flying boats of Ansett Flying Boat Services operating out of Rose Bay, Sydney, and landing on the lagoon, the journey taking about 3½ hours. When Lord Howe Island Airport was completed in 1974, the seaplanes were eventually replaced with QantasLink twin-engined turboprop Dash 8-200 aircraft.[54]

21st century

In 2002, the Royal Navy destroyer HMS Nottingham struck Wolf Rock, a reef at Lord Howe Island, and almost sank.[55] In recent times, tourism has increased and the government of New South Wales has been increasingly involved with issues of conservation.[11]

On 17 October 2011, a supply ship, M/V Island Trader, with 20 tons of fuel, ran aground in the lagoon. The ship refloated at high tide with no loss of crew or cargo.[56]

The 2016 film The Shallows starring Blake Lively was largely filmed on the island.[57]

One of the most contentious issues amongst islanders in the 21st century is what to do about the rodent situation. Rodents have only been on the island since the SS Makambo ran aground in 1918, and have wiped out several endemic bird species and were thought to have done the same to the Lord Howe Island stick insect. A plan has been made to drop 42 tonnes of rat bait across the island, but the community is heavily divided.[58]

Demographics

As at the 2016 census, the resident population was 382 people,[59] and the number of tourists was not allowed to exceed 400.[60] Early settlers were European and American whalers and many of their offspring have remained on the island for more than six generations. Residents are now involved with the kentia palm industry, tourism, retail, some fishing, and farming. In 1876 on Sundays, games and labour were suspended, but no religious services were held.[48] Nowadays, the area known locally as Church Paddock has Anglican, Catholic, and Adventist churches, the religious affiliations on the island being 30% Anglican, 22% no religion, 18% Catholic and 12% Seventh Day Adventist.[61] The ratio of the sexes is roughly equal, with 47% of the population in the age group 25–54 and 92% holding Australian citizenship.[61]

Governance and land tenure

Official control of Lord Howe Island lay initially with the British Crown until it passed to New South Wales in 1855,[44][62] although until at least 1876, the islanders lived in "a relatively harmonious and self-regulating community".[63] In 1878, Richard Armstrong was appointed administrator when the NSW Parliament declared the island a forest reserve, but as a result of ill feeling, and an enquiry, he was eventually removed from office on 31 May 1882 (he returned later that year though to view the transit of Venus from present-day Transit Hill).[64] After his removal, the island was administered by four successive magistrates until 1913, when a Sydney-based board was formed; in 1948, a resident superintendent was appointed.[65] In 1913, the three-man Lord Howe Island Board of Control was established, mostly to regulate the palm seed industry, but also administering the affairs of the island from Sydney until the present Lord Howe Island Board was set up in 1954.[66]

The Lord Howe Island Board is a NSW Statutory Authority established under the Lord Howe Island Act 1953, to administer the island as part of the state of New South Wales. It reports directly to the state's Minister for Environment and Heritage, and is responsible for the care, control, and management of the island. Its duties include the protection of World Heritage values; the control of development; the administration of Crown Land, including the island's protected area; provision of community services and infrastructure; and regulating sustainable tourism.[13] In 1981, the Lord Howe Island Amendment Act gave islanders the administrative power of three members on a five-member board.[67] The board also manages the Lord Howe Island kentia palm nursery, which together with tourism, provides the island's only sources of external income.[13] Under an amendment bill in 2004, the board now comprises seven members, four of whom are elected from the islander community,[13] thus giving about 350 permanent residents a high level of autonomy. The remaining three members are appointed by the minister to represent the interests of business, tourism, and conservation.[13] The full board meets on the island every three months, while the day-to-day affairs of the island are managed by the board's administration, with a permanent staff that had increased to 22 people by 1988.[68]

Land tenure has been an issue since first settlement, as island residents repeatedly requested freehold title or an absolute gift of cultivated land.[69] Original settlers were squatters. The granting of a 100-acre (40 ha) lease to Richard Armstrong in 1878 drew complaints, and a few short-term leases ("permissive occupancies") were granted.[70] In 1913, with the appointment of a board of control, permissive occupancies were revoked and the board itself given permissive occupancy of the island.[71] Then the Lord Howe Island Act 1953 made all land the property of the Crown. Direct descendants of islanders with permissive occupancies in 1913 were granted perpetual leases on blocks up to five acres (2.0 ha) for residential purposes. Short-term special leases were granted for larger areas used for agriculture, so in 1955, 55 perpetual leases and 43 special leases were granted.[72] The 1981 amendment to the act extended political and land rights to all residents of 10 years or more.[72] An active debate exists concerning the proportion of residents with tenure and the degree of influence on the board of resident islanders in relation to long-term planning for visitors, and issues relating to the environment, amenity, and global heritage.[70]

Kentia palm industry

The first exporter of palm seeds was Ned King, a mountain guide for the Fitzgerald surveys of 1869 and 1876, who sent seed to the Sydney Botanic Gardens. Overseas trade began in the 1880s, when one of the four palms endemic to the island, kentia palm (Howea forsteriana), which grows naturally in the lowlands, was found to be ideally suited to the fashionable conservatories of the well-to-do in Britain, Europe, and the United States,[14][51] but the assistance of mainland magistrate Frank Farnell was needed to put the business on a sound commercial footing when in 1906, he became director of a company, the Lord Howe Island Kentia Palm Nursery, whose shareholders included 21 islanders and a Sydney-based seed company. However, the formation of the Lord Howe Island Board of Control was needed in 1913 to resolve outstanding issues.[73]

The native kentia palm (known locally as the thatch palm, as it was used to thatch the houses of the early settlers) is now the most popular decorative palm in the world. The mild climate of the island has evolved a palm that can tolerate low light, a dry atmosphere and lowish temperatures—ideal for indoor conditions.[14] Up to the 1980s the palms were only sold as seed but from then onwards only as high quality seedlings. The nursery received certification in 1997 for its high quality management complying with the requirements of Australian Standard AS/NZS ISO 9002.[74]

Seed is gathered from natural forest and plantations, most collectors being descendants of the original settlers. Seed is then germinated in soil-less media and sealed from the atmosphere to prevent contamination. After testing, they are picked, washed (bare-rooted), sanitized, and certified then packed and sealed into insulated containers for export. They grow both indoors and out and are popular for hotels and motels worldwide. Nursery profits are returned to enhance the island ecosystem. The nursery plans to expand the business to include the curly palm and other native plants of special interest.[14]

Tourism

Lord Howe Island is known for its geology, birds, plants, and marine life. Popular tourist activities include scuba diving, birdwatching, snorkelling, surfing, kayaking, and fishing.[75] To relieve pressure on the small island environment, only 400 tourists are permitted at any one time.[60] The island is reached by plane from Sydney Airport or Brisbane Airport in less than two hours.[60] The Permanent Park Preserve declared in 1981 has similar management guidelines to a national park.[76]

Facilities

With fewer than 800 people on the island at any time, facilities are limited; they include a bakery, butcher, general store, liquor store, restaurants, post office, museum, and information centre, a police officer, a ranger, and an ATM at the bowling club. Stores are shipped to the island fortnightly by the Island Trader from Port Macquarie.[52] The island has a small four-bed hospital and dispensary.[77] A small botanic garden displays labelled local plants in its grounds. Diesel-generated power is 240 volts AC, as on the mainland.[77] No public transport or mobile phone coverage is available, but public telephones, fax facilities, and internet access are,[77] as well as a local radio station and newsletter, The Signal.

Tourist accommodation ranges from luxury lodges to apartments and villa units.[78] The currency is the Australian dollar, and there are two banks.[77] No camping facilities are on the island and remote-area camping is not permitted.[78] To protect the fragile environment of Ball's Pyramid (which carries the last remaining wild population of the endangered Lord Howe Island stick insect), recreational climbing there is prohibited. No pets are allowed without permission from the board. Islanders use tanked rainwater, supplemented by bore water for showers and washing clothes.[79]

Activities

As distances to sites of interest are short, cycling is the main means of transport on the island. Tourist activities include golf (9-hole), lawn bowls, tennis, fishing (including deep-sea game fishing), yachting, windsurfing, kitesurfing, kayaking, and boat trips (including glass-bottom tours of the lagoon).[80][81] Swimming, snorkelling, and scuba diving are also popular in the lagoon, as well as off Tenth of June Island, a small rocky outcrop in the Admiralty group where an underwater plateau drops 36 m (118 ft) to reveal extensive gorgonia and black corals growing on the vertical walls. Other diving sites are found off Ball's Pyramid, 26 km (16 mi) away, where trenches, caves, and volcanic drop-offs occur.[82]

Bushwalking, natural history tours, talks, and guided walks take place along the many tracks, the most challenging being the eight-hour guided hike to the top of Mount Gower.[83] The island has 11 beaches, and hand-feeding the 1 m-long (3 ft) kingfish (Seriola lalandi) and large wrasse at Ned's Beach is very popular.[84] Walking tracks cover the island with difficulty graded from 1–5, they include—in the north: Transit Hill 2-hour return, 2 km (1.2 mi); Clear Place, 1– to 2-hour return; Stevens Reserve; North Bay, 4-hour return, 4 km (2.5 mi); Mount Eliza; Old Gulch, 20-minute return, 300 m (330 yd); Malabar Hill and Kims Lookout, 3 or 5-hour return, 7 km (4.3 mi) and—in the south: Goat House Cave, 5-hour return, 6 km (3.7 mi); Mount Gower, 8-hour return, 14 km (8.7 mi); Rocky Run and Boat Harbour; Intermediate Hill, 45-minute return, 1 km (0.62 mi); and Little Island, 40-minute return, 3 km (1.9 mi). Recreational climbers must obtain permission from the Lord Howe Island Board.[85][86]

Geography

Lord Howe Island is an irregularly crescent-shaped volcanic remnant in the southwest Pacific Ocean. Lying in the Tasman Sea between Australia and New Zealand, the island is 600 km (370 mi) east of mainland Port Macquarie, 702 km (436 mi) northeast of Sydney, and about 772 km (480 mi) from Norfolk Island to its northeast.[87] The island is about 10 km (6.2 mi) long and between 0.3 and 2.0 km (0.19 and 1.24 mi) wide with an area of 14.55 km2 (5.62 sq mi). Along the west coast is a semienclosed, sheltered coral reef lagoon with white sand, the most accessible of the island's 11 beaches.

Both the north and south sections of the island are high ground of relatively untouched forest, in the south comprising two volcanic mountains, Mount Lidgbird (777 m (2,549 ft)) and Mount Gower which, rising to 875 m (2,871 ft), is the highest point on the island.[88] The two mountains are separated by the saddle at the head of Erskine Valley. In the north, where most of the population live, high points are Malabar (209 m (686 ft)) and Mount Eliza (147 m (482 ft)). Between these two uplands is an area of cleared lowland with some farming, the airstrip, and housing. The Lord Howe Island Group of islands comprises 28 islands, islets, and rocks. Apart from Lord Howe Island itself, the most notable of these is the pointed rocky islet Balls Pyramid, a 551 m-high (1,808 ft) eroded volcano about 23 km (14 mi) to the southeast, which is uninhabited by humans but bird-colonised.[89] It contains the only known wild population of the Lord Howe Island stick insect, formerly thought to be extinct.[90] To the north is the Admiralty Group, a cluster of seven small, uninhabited islands.[7] Just off the east coast is 4.5 ha (11 acres) Mutton Bird Island, and in the lagoon is the 3 ha (7.4 acres) Blackburn (Rabbit) Island.

Geological origins

Lord Howe Island is the highly eroded remains of a 7-million-year-old shield volcano,[91] the product of eruptions that lasted for about 500,000 years.[92] It is one of a chain of islands that occur on the western rim of an undersea shelf, the Lord Howe Rise, which is 3,000 km (1,900 mi) long and 300 km (190 mi) wide extending from New Zealand to the west of New Caledonia and consisting of continental rocks that separated from the Australian plate 60 to 80 million years ago to form a new crust in the deep Tasman Basin.[93] The shelf is part of Zealandia, a microcontinent nearly half the size of Australia that gradually submerged after breaking away from the Gondwanan supercontinent.[94] The Lord Howe Seamount Chain is defined by coral-capped guyots stretching to the north of the island for 1,000 km (620 mi) and including the Middleton (220 km (140 mi) away) and Elizabeth (160 km (99 mi) away) reefs of the Elizabeth and Middleton Reefs Marine National Park Reserve. This chain of nine volcanic peaks was probably produced by the northward movement of the Indo-Australian Plate over a stationary hotspot, so the oldest guyots were the first formed and most northerly as the plate moved northward at a rate of 6 cm (2.4 in) per year (see plate tectonics).[95][96]

Basalts and calcarenite

Two periods of volcanic activity produced the major features of the island. The first about 6.9 million years (Mya) ago produced the northern and central hills, while the younger and highly eroded Mount Gower and Mount Lidgbird were produced about 6.3 Mya by successive basalt (an extrusive igneous rock) lava flows that once filled a large volcanic caldera (crater)[97] and can now be seen as horizontal basalt strata on mountain cliffs (at Malabar and Mount Gower) occasionally interspersed with dikes (vertical lava intrusions).[98][99] Geological pyroclastic remnants of volcanic eruption can be seen on the 15 ha (37-acre) Roach Island (where the oldest rocks occur) and Boat Harbour as tuff (ash), breccia (with angular blocks), and agglomerate (rounded 'bombs').[14] Offshore on the Lord Howe Rise, water depths reach 2,000 m (6,600 ft) falling to 4,000 m (13,000 ft) to the west of the rise. From the dimensions of the rock on which the island stands, the island has been calculated to erode to 1/40th of its original size.[100]

Rocks and land at the foot of these mountains is calcarenite, a coral sand, blown inland during the Pleistocene between 130,000 and 20,000 years ago and cemented into stratified layers by water percolation.[101] In this rock are fossils of bird bones and eggs, land and marine snails, and the extinct endemic horned turtle (Meiolania platyceps) now thought to be an ancient relictual nonswimming tortoise with relatives in South America.[102] The crescent of the island protects a coral reef] and lagoon, the barrier reef, at 31°S, is the most southerly in the world.[103] Beach sands, rather than consisting of quartz grains derived from granite, as on the mainland, are made of fragments of shell, coral, and coralline algae, together with basalt grains, and basaltic minerals such as black diopside and green olivine.[104] The lowland consists of alluvial soils.

The island continues to erode rapidly and is expected to be fully submerged within 200,000 years, taking an appearance akin to the Middleton and Elizabeth Reefs.[105]

Climate

Lord Howe Island has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa under the Köppen climate classification).[106]

In general, the summers are warm-hot with rainfall erratic, but occasionally heavy, while in winter it is very mild with rainfall more or less uniform. There is a gradual transition from summer to winter conditions and vice versa.[107] Winds are frequent and salt-laden, being moderate easterlies in the summer and fresh to strong westerlies in the winter.[107][108] July is the windiest month,[109] and the winter months are subject to frequent gales and strong winds. The island has 67.8 clear days, annually.[107]

Storms and occasional cyclones also affect the island.[107] Rainfall records are maintained in the north, where rainfall is less than in the frequently cloud-shrouded mountains of the south. Wide variation in rainfall can occur from year to year. July and August are the coldest months with average minimum temperatures around 13 °C (55 °F) and no frost. Average maximum temperatures range from 17–20 °C (63–68 °F) in the winter to 24–27 °C (75–81 °F) in the summer. The humidity averages in the 60–70% range year round, becoming more noticeable on warmer summer days than in the cooler winter months.[110][111]

The average temperature of the sea ranges from 20.0 °C (68.0 °F) in July, August, and September to 25.3 °C (77.5 °F) in March.[112]

| Climate data for Lord Howe Island | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 29.9 (85.8) |

31.3 (88.3) |

28.2 (82.8) |

27.0 (80.6) |

25.2 (77.4) |

23.9 (75.0) |

22.4 (72.3) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.3 (73.9) |

24.9 (76.8) |

28.0 (82.4) |

28.3 (82.9) |

31.3 (88.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 25.3 (77.5) |

25.7 (78.3) |

24.8 (76.6) |

23.2 (73.8) |

21.4 (70.5) |

19.8 (67.6) |

18.9 (66.0) |

18.9 (66.0) |

20.0 (68.0) |

20.8 (69.4) |

22.3 (72.1) |

24.0 (75.2) |

22.1 (71.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 20.6 (69.1) |

21.0 (69.8) |

20.0 (68.0) |

18.0 (64.4) |

16.3 (61.3) |

14.8 (58.6) |

13.9 (57.0) |

13.5 (56.3) |

14.6 (58.3) |

15.7 (60.3) |

17.4 (63.3) |

19.2 (66.6) |

17.1 (62.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 13.1 (55.6) |

14.7 (58.5) |

13.4 (56.1) |

11.2 (52.2) |

9.1 (48.4) |

7.5 (45.5) |

6.6 (43.9) |

6.6 (43.9) |

5.9 (42.6) |

7.8 (46.0) |

9.2 (48.6) |

11.4 (52.5) |

5.9 (42.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 113.5 (4.47) |

112.6 (4.43) |

131.9 (5.19) |

134.2 (5.28) |

157.7 (6.21) |

173.1 (6.81) |

141.0 (5.55) |

107.7 (4.24) |

110.7 (4.36) |

106.1 (4.18) |

110.3 (4.34) |

102.4 (4.03) |

1,499 (59.02) |

| Average precipitation days | 13.1 | 13.2 | 15.9 | 18.6 | 20.8 | 21.7 | 23.2 | 20.4 | 16.5 | 14.3 | 13.6 | 13.5 | 204.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 69 | 66 | 67 | 67 | 66 | 66 | 66 | 64 | 68 | 68 | 67 | 66 | 67 |

| Source: [113] | |||||||||||||

Flora and fauna

Plants

Lord Howe Island is a distinct terrestrial ecoregion known as the Lord Howe Island subtropical forests. It is part of the Australasia ecozone and shares many biotic affinities with Australia, New Guinea, and New Caledonia.[114] Almost half of the island's native plants are endemic and many of the island's unique plants grow on or around the mountain summits where the height has allowed the development of a true cloud forest and many different microhabitats from sea level to the summits.[115] One of the best known is Howea, an endemic genus of palms (Arecaceae) that are commonly known as kentia palms and are popular houseplants.[116] Annual exports provide a revenue of over A$2 million, providing the only major industry on the island apart from tourism.[117]

Origin

In geological terms at 7 million years old, Lord Howe Island is relatively young and was never part of any continent, its flora and fauna colonising the island from across the sea, carried by wind, water, or birds, possibly assisted at a geological time when other islands were exposed, enabling island hopping.[118] Nevertheless, it is far enough away and has had sufficient time to evolve endemic species. The high degree of endemism is emphasised by the presence of five endemic genera: Negria, Lordhowea, Howea, Lepidorrhachis, and Hedyscepe.[119] Island plants are similar to those of Norfolk Island, the two islands sharing some endemic species, for example, the critically endangered species of creeping vine Calystegia affinis. The combined flora of these two islands is more closely related to that of New Zealand and New Caledonia than to that of Australia.[119] Also, a small but clear link exists with the plants of Vanuatu.[119] The closest mainland affinities are with the vegetation of subtropical southeastern Queensland. A link with Gondwanaland is indicated by the presence of endemic species such as the wedding lily (Dietes robinsoniana) whose only living relatives occur in South Africa.[120]

The flora of the island is relatively untouched with a large number of rare plants, 44% being endemic to the island.[119] With a diversity of conditions ranging from valleys, to ridges, plains, and misty mountain tops, habitat is available for a wide range of plant communities, which have been comprehensively analysed and mapped.[121] Mosses include Spiridens muelleri. There are 57 species of ferns, of which 25 are endemic: they are most abundant in the moist environments of the southern island, especially the higher parts of Mount Gower,[122] perhaps the most apparent being the four endemic tree ferns in the genus Cyathea that occur on the southern mountains.[123]

| Total | Indigenous | Endemic | Naturalised |

|---|---|---|---|

| 459 | 241 | 105 (43.6%) | 218 (47.5%) |

Communities and special plants

Plant communities have been classified into nine categories: lowland subtropical rainforest, submontane rainforest, cloud-forest and scrub, lowland swamp forest, mangrove scrub and seagrass, coastal scrub and cliff vegetation, inland scrub and herbland, offshore island vegetation, shoreline and beach vegetation, and disturbed vegetation.[119] Several plants are immediately evident to the visitor. Banyan (Ficus macrophylla subsp. columnaris) is a remarkable tree with a buttressed trunk and pendulous aerial roots; it can be seen on the track to Clear Place and near Ned's Beach.[124] Pandanus tree (Pandanus forsteri) has spectacular teepee-like prop roots and pineapple-like fruits that are orange-red when mature, the tough leaves being used for basketry. It occurs in damp areas such as creek beds, and fine specimens can be seen along the Boat Harbour track.[124] Ten species of orchids are on the island, the most noticeable being the bush orchid (Dendrobium macropus subsp. howeanum) on lowland trees and rocks, bearing cream flowers from August to September.[124] Other prominent flowering plants in the summer include, on the mountain slopes, the whiskery red flowers of mountain rose (Metrosideros nervulosa and Metrosideros sclerocarpa), the massed, small, yellow flowers of corokia (Corokia carpodetoides), orange, plump flowers of pumpkin tree (Negria rhabdothamnoides), and white spikes of Fitzgerald tree (Dracophyllum fitzgeraldii).[124] The kava bush has large, aromatic, heart-shaped leaves. After heavy rain, the endemic glowing mushrooms Mycena chlorophanos and Omphalotus nidiformis can be found in the palm forests.[125]

The palms are the signature plants of the island as the kentia and curly palms especially dominate the landscape in many places, the kentia being of special economic importance.[126] All four species are endemic to the island, often occurring in dense, pure stands, the one that has proved such a worldwide success as an indoor plant being the kentia or thatch palm (Howea forsteriana). This is a lowland palm with drooping leaflets and seed branches in 'hands' of three to five, while the curly palm (H. belmoreana), which occurs on slightly higher ground, has upwardly directed leaflets and solitary 'hands'. Natural hybrids between these species occur on the island and a mature specimen of one is growing in the island nursery. On the mountain sides higher than about 350 m, the big mountain palm (Hedyscepe canterburyana) occurs; it has large, golf ball-sized fruits, while the little mountain palm (Lepidorrhachis mooreana) has marble-sized fruits and is only found on the mountain summits.[127]

Images of native flora

|

|

|

|

|

| Tall kentia palms | Curly palm | Lord Howe bird's nest fern | ||

| (Howea forsteriana) | (Howea belmoreana) | (Asplenium australasicum) | (Asplenium milnei) | (Lagunaria patersonia) |

Animals

No snakes nor highly venomous or stinging insects, animals, or plants occur, and no dangerous daytime sharks are found off the beaches, although tiger sharks have been reported on the cliff side of the island.[128]

Birds

A total of 202 different birds have been recorded on the island. Eighteen species of land birds breed on the island and many more migratory species occur on the island and its adjacent islets, many tame enough that humans can get quite close.[129] The island has been identified by BirdLife International as an endemic bird area, and the Permanent Park Preserve as an important bird area, because it supports the entire population of Lord Howe woodhens, most of the breeding population of providence petrels, over 1% of the world population of another five seabird species, and the whole populations of three endemic subspecies.[130]

Fourteen species of seabirds breed on the island.[129] Red-tailed tropicbirds can be seen in large numbers circling the Malabar cliffs, where they perform acrobatic courting rituals.[131] Between August and May, thousands of flesh-footed and wedge-tailed shearwaters return to the island at dusk each day. From the Little Island Track between March and November, one of the world's rarest birds, the providence petrel, also performs courtship displays during winter breeding, and it is extremely tame. The island was its only breeding location for many years after the breeding colony on Norfolk Island was exterminated in the late 19th century,[132] though a small population persists on the adjacent Phillip Island. The Kermadec petrel was discovered breeding on Mount Gower in 1914 by ornithologist Roy Bell while collecting specimens for Gregory Mathews[133] and the black-winged petrel was only confirmed as a breeder in 1971; its numbers have increased following the elimination of feral cats from the island.[134]

The flesh-footed shearwater, which breeds in large numbers on the main island in spring-autumn, once had its chicks harvested for food by the islanders.[135] The wedge-tailed and little shearwaters breed on the main island and surrounding islets, though only a small number of the latter species can be found on the main island. Breeding white-bellied storm petrels were another discovery by Roy Bell.[136] Masked boobies are the largest seabirds breeding on Lord Howe[137] and can be seen nesting and gliding along the sea cliffs at Mutton Bird Point all year round. Sooty terns can be seen on the main island at Ned's and Middle Beaches, North Bay, and Blinkey Beach; the most numerous of the island's breeding seabirds, their eggs were formerly harvested for food. Common and black noddies build nests in trees and bushes, while white terns lay their single eggs precariously in a slight depression on a tree branch,[138] and grey ternlets lay their eggs in cliff hollows.[139]

Three endemic passerine subspecies are the Lord Howe golden whistler, Lord Howe silvereye, and Lord Howe currawong.[140] The iconic endemic rail, the flightless Lord Howe woodhen, is the only surviving member of its genus; its ancestors could fly, but with no predators and plenty of food on the island, this ability was lost. This made it easy prey for islanders and feral animals, so by the 1970s, the population was less than 30 birds. From 1978 to 1984, feral animals were removed and birds were raised in captivity to be successfully reintroduced to the wild. The population is now relatively safe and stable.[14][141]

List of endemic birds

- Lord Howe currawong, Strepera graculina crissalis (vulnerable, subspecies of pied currawong)

- Lord Howe golden whistler, Pachycephala pectoralis contempta (least concern, subspecies of golden whistler)

- Lord Howe silvereye, Zosterops lateralis tephropleurus (vulnerable, subspecies of silvereye)

- Robust white-eye, Zosterops strenuus (extinct)

- Lord Howe gerygone, Gerygone insularis (extinct)

- Lord Howe fantail, Rhiphidura fuliginosa cervina (extinct, subspecies of NZ fantail)

- Lord Howe starling, Aplonis fusca hulliana (extinct, subspecies of extinct Tasman starling)

- Lord Howe thrush, Turdus poliocephalus vinitinctus (extinct, subspecies of Island thrush)

- Lord Howe parakeet, Cyanoramphus subflavescens (extinct)

- Lord Howe boobook, Ninox novaeseelandiae albaria (extinct)

- Lord Howe woodhen, Gallirallus sylvestris (endangered)

- Lord Howe swamphen, Porphyrio albus (extinct)

- Lord Howe pigeon, Columba vitiensis godmanae (extinct)

Mammals, reptiles and amphibians

Only one native mammal remains on the islands, the large forest bat. The endemic Lord Howe long-eared bat is known only from a skull and is now presumed extinct, possibly the result of the introduction of ship rats.[142]

Two terrestrial reptiles are native to the island group: the Lord Howe Island skink and the Lord Howe Island gecko. Both are rare on the main island, but more common on smaller islands offshore.[143] The garden skink and the bleating tree frog have been accidentally introduced from the Australian mainland. During the Pleistocene the giant terrestrial tortoise Meiolania platyceps was endemic to the island, but this is currently thought to have gone extinct before human occupation as a result of postglacial sea-level rise.

Invertebrates

The Lord Howe Island stick insect disappeared from the main island soon after the accidental introduction of rats when the SS Makambo ran aground near Ned's Beach on 15 June 1918.[143][144] In 2001, a tiny population was discovered in a single Melaleuca howeana shrub on the slopes of Ball's Pyramid,[145] has been successfully bred in captivity, and is nearing re-introduction to the main island.[146] The Lord Howe stag beetle is a colourful endemic beetle seen during summers.[147] Another endemic invertebrate, the Lord Howe flax snail (or Lord Howe Placostylus), has also been affected by the introduction of rats.[143] Once common, the species is now endangered and a captive-breeding program is underway to save the snail from extinction.

Marine life

Marine environments are near-pristine with a mixtures of temperate, subtropical, and tropical species derived from cool-temperate ocean currents in the winter and the warm East Australian Current, which flows from the Great Barrier Reef, in summer.[148] Of the 490 fish species recorded, 13 are endemic and 60% are tropical.[148] The main angling fish are yellowtail kingfish and New Zealand bluefish, while game fish include marlin, tuna, and giant kingfish called "greenbacks".[149] Over 80 species of corals occur in the reefs surrounding the islands.[150][151] Australian underwater photographer Neville Coleman has photographed various nudibranchs at Lord Howe Island.[152]

Various species of cetaceans inhabit or migrate through the waters in vicinity, but very little about their biology in the area is known due to lack of studies and sighting efforts caused from locational conditions. Bottlenose dolphins are the most commonly observed and are the only species confirmed to be seasonal or yearly residents, while some other dolphin species have also been observed.[153] Humpback whales are the only large whales showing slow but steady recoveries as their numbers annually migrating past the island of Lord Howe are much smaller than those migrating along Australian continent.

Historically, migratory whales such as blue, fin, and sei whales were very abundant in the island waters, but were severely reduced in numbers to near-extinction by commercial and illegal hunts, including the mass illegal hunts by the Soviet Union and Japan in the 1960s to 1970s.[154] Southern right and sperm whales were most severely hunted among these, hence the area was called the Middle Ground by whalers.[155] These two were likely once seasonal residents around the island, where right whales prefer sheltered, very shallow bays,[156] while sperm whales mainly inhabit deep waters.

Providence petrels on the summit of Mount Gower

Providence petrels on the summit of Mount Gower Woodhen by Neds Beach Road

Woodhen by Neds Beach Road- Masked booby with chick viewed off Malabar cliffs

Coral Skeleton on Little Island Beach

Coral Skeleton on Little Island Beach

Conservation

About 10% of Lord Howe Island's forests has been cleared for agriculture, and another 20% has been disturbed, mostly by domestic cattle and feral sheep, goats, and pigs. As a result, 70% of the island remains relatively untouched, with a variety of plants and animals, many of which are endemic, and some of which are rare or threatened.[157] Two species of plants, nine terrestrial birds, one bat, and at least four invertebrates have become extinct since 1778.[158] Endemism at the generic level includes the palms Howea, Hedyscepe and Lepidorrhachis, a woody daisy Lordhowea, the tree Negria, the leech Quantenobdella howensis, three annelid worm genera (Paraplutellus, Pericryptodrilus and Eastoniella), an isopod shrimp Stigmops, a hemipteran bug Howeria, and a cricket Howeta.[159]

The Lord Howe Island Board instigated an extensive biological and environmental survey (published in 1974), which has guided the island conservation program.[160] In 1981, the Lord Howe Island Amendment Act proclaimed a "Permanent Park Preserve" over the north and south ends of the island. Administration of the preserve was outlined in a management plan for the sustainable development of the island prepared by the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service,[76][161] which has a ranger stationed on the island. The island was cited under the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1982.

Offshore environmental assets are protected by the Lord Howe Island Marine Park. This consists of a state marine park managed by the Marine Parks Authority of New South Wales in the waters out to three nautical miles around the island and including Ball's Pyramid.[19] It also includes a Commonwealth Marine Park extending from 3 to 12 nautical miles out and managed by the federal Department of the Environment and Heritage.[162] In total the Marine Park covers about 3,005 km2 (1,160 sq mi).[163]

Feral animals and plants

Pigs and goats were released on the island as potential food sources in the early 1800s; the goats destroyed shrubs and grasses used as nesting sites and the pigs ate eggs and chicks and disturbed the land by rooting for food.[164] Several birds have become extinct on the island since the arrival of humans. The first round of extinctions included the Lord Howe swamphen or white gallinule, the white-throated pigeon, the red-crowned parakeet, and the Tasman booby, which were eliminated by visitors and settlers during the 19th century, either from overhunting for food or protection of crops.[164] Black rats were released from provisioning whaling ships in the 1840s and mice from Norfolk Island in 1860.[164] In 1918, the black rat was accidentally introduced with the shipwreck of the S.S. Makambo, which ran aground at Ned's Beach. This triggered a second wave of extinctions, including the vinous-tinted thrush, the robust white-eye, the Lord Howe starling, the Lord Howe fantail and the Lord Howe gerygone, as well as the destruction of the native phasmid and the decimation of palm fruits.[165] Bounties were offered for rat and pig tails and 'ratting' became a popular pursuit. Subsequent poisoning programs have kept populations low.[166] The Lord Howe boobook may have become extinct through predation by, or competition with, the Tasmanian masked owls, which were introduced in the 1920s in a failed attempt to control the rat population.[164] Stray dogs are also a threat, as they could harm the native woodhen and other birds.[167]

Invasive plants such as Crofton weed[168] and Formosa lily[169] occur in inaccessible areas and probably cannot be eradicated, but others are currently being managed.[170] In 1995, the first action was taken to control the spread of introduced plants on the island, chiefly ground asparagus and bridal creeper, but also cherry guava, Madeira vine, Cotoneaster, Ochna, and Cestrum. This has been followed by weeding tours and the formation of the Friends of Lord Howe Island group in 2000. Programs have also been started to remove weeds from private properties and re-vegetate some formerly cultivated areas.[171] An environmental unit was created by the board and it includes a flora management officer and a permanent weed officer. Weeds have been mapped and an eradication program is in place, supported by improved education and quarantine procedures.[172]

Introduced species that harmed Lord Howe's native flora and fauna, namely feral pigs, cats and goats, were eradicated by the early 2000s.[141][173][171][174]

In July 2012, the Australian federal Environment Minister Tony Burke and the New South Wales Environment Minister Robyn Parker announced that the Australian and New South Wales governments would each contribute 50% of the estimated A$9 million cost of implementing a rodent eradication plan for the island, using aerial deployment of poison baits.[175] The plan was put to a local vote and is considered controversial.[176] Around 230 woodhens were captured before the rodent eradication commenced in early 2019. Following the successful eradication of the rodents, all woodhens and currawongs were released across the island in late 2019 and early 2020.[177]

A recovery program has restored the Lord Howe woodhen's numbers from only 20 in 1970 to about 200 in 2000, which is close to carrying capacity.[167]

Climate change

According to an analysis by Tim Flannery, the ecosystem of Lord Howe Island is threatened by climate change and global warming, with the reefs at risk from rises in water temperature.[103][178][179] The first international conference on global artificial photosynthesis as a climate-change solution occurred at Lord Howe Island in 2011,[180] the papers being published by the Australian Journal of Chemistry.[181]

Heritage listings

The Lord Howe Islands Group was inscribed on the World Heritage List for its unique landforms and biota, its diverse and largely intact ecosystems, natural beauty, and habitats for threatened species. It also has significant cultural heritage associations in the history of NSW.[18]

Lord Howe Island and adjacent islets, Admiralty Islands, Mutton Bird Islands, Ball's Pyramid, and associated coral reefs and marine environs were added to the Australian National Heritage List on 21 May 2007, on the basis of the World Heritage List.[17]

Lord Howe Island was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.[18]

In September 2019 it was revealed that, in 2017, federal environment minister Josh Frydenberg overruled a recommendation from his department to install two wind turbines. The project, which would have substantially reduced the Island's dependence on diesel-powered electricity generators, had been considered not to endanger the Island's heritage status and was supported by the Islanders.[182]

References

- "Regional Statistics – New South Wales" (PDF). Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2004. Retrieved 19 April 2009.

- "Port Macquarie". New South Wales Electoral Commission. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- "Profile of the Electoral Division Sydney". Australian Electoral Commission. 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Lord Howe Island (State Suburb)". 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- "Draft Report: Review of the Lord Howe Island Act of 1954" (PDF). State of New South Wales, Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water, February 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 March 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- "Lord Howe Island Group". Australian Government Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- Hutton 1986, p. 81

- Nichols 2006, p. 4

- Hutton 1986, p. 1

- Nichols 2006, p. 28

- Hutton 1986, p. 2

- Nichols 2006, p. 74

- "Lord Howe Island Board". Lord Howe Island Tourism Association. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- "LHI Tourist Agency Fact Sheets". Lord Howe Island Tourism Association. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- "Lord Howe Island Group". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 2009. Retrieved 20 April 2009.

- Hutton 1986, pp. 5–6

- "Lord Howe Island Group, Lord Howe Island, NSW, Australia (Place ID 105694)". Australian Heritage Database. Department of the Environment. 21 May 2007.

- "Lord Howe Island Group". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H00970. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "Lord Howe Island Marine Park". New South Wales Government Marine Parks Authority. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- "Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia (IBRA7) regions and codes". Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. Commonwealth of Australia. 2012. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- Nichols 2006, p. 5

- Rabone 1972, p. 10

- "Arthur Bowes-Smyth, illustrated journal, 1787–1789. Titled 'A Journal of a Voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China in the Lady Penrhyn, Merchantman William Cropton Sever, Commander by Arthur Bowes-Smyth, Surgeon – 1787-1788-1789'; being a fair copy compiled ca 1790". catalogue. State Library of New South Wales. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- See Hutton 1986

- Lord Howe Island: 1788–1988 (PDF). National Library of Australia. 1988. ISBN 978-0-7316-3090-5. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- Nichols 2006, p. 8

- Nichols 2006, p. 21

- Nichols 2006, pp. 23–24

- Nichols 2006, p. 17

- Nichols 2006, p. 32

- Rabone 1972, p. 38

- Rabone 1972, p. 23

- Rabone 1972, pp. 26–30

- Nichols 2006, p. 34

- Nichols 2006, p. 24

- Rabone 1972, p. 30

- Nichols 2006, p. 36

- Nichols 2006, p. 30

- Nichols 2006, pp. 38–40

- Rabone 1972, pp. 30–31

- See Starbuck 1878

- Hutton 1986, pp. 2,44

- Rabone 1972, p. 33

- "New South Wales Constitution Act 1855 (UK)". Museum of Australian Democracy. 1855. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- Nichols 2006, pp. 58–59

- Mueller 1875, pp. 76–79

- See Hill 1870

- Rabone 1972, p. 40

- Nichols 2006, pp. 76–77, 82–3

- Wilson, (1882)

- Green 1994, p. 15

- Nichols 2006, p. 139

- Nichols 2006, p. 132

- Hutton 1986, pp. 3–4

- "Battle to save stricken warship". BBC News. 7 July 2002. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- The Law Offices of Countryman & McDaniel. Cargolaw.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-16.

- Behind the scenes facts about The Shallows Cosmopolitan.com

- Trouble in Paradise: Lord Howe divided over plans to exterminate rats www.theguardian.com

- "2016 Census QuickStats: Lord Howe Island". www.censusdata.abs.gov.au. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- "Accommodation on Lord Howe Island". Lord Howe Island Tourism Association. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (31 October 2012). "Lord Howe Island (State Suburb)". 2011 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- White, Michael (2010). Australian Offshore Laws. The Federation Press. p. 305. ISBN 978-1-86287-742-9.

- Nichols 2006, p. 106

- Nichols 2006, pp. 82–83

- Nichols 2006, pp. 87,106

- Nichols 2006, pp. 107–108

- Hutton 1986, p. 3

- Lord Howe Island: 1788–1988 (PDF). National Library of Australia. 1988. ISBN 978-0-7316-3090-5. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- Nichols 2006, pp. 110–115

- Nichols 2006, p. 110

- Nichols 2006, p. 111

- Nichols 2006, p. 114

- Nichols 2006, pp. 98–105

- "NY520 – Implementation of quality management in Lord Howe Island Kentia Palm Nursery". Nursery & Garden Industry Australia. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- "Lord Howe Island". Visit NSW. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- Nichols 2006, p. 117

- "Getting to Lord Howe Island factsheet" (PDF). Lord Howe Island Tourism Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 September 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-20.

- "Lord Howe Island Accommodation Directory". Lord Howe Island Tourism Association. Archived from the original on 31 August 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- "Nature experiences on Lord Howe Island". Lord Howe Island Tourism Association. Archived from the original on 17 September 2011. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- Nichols 2006, pp. 166–171

- "LHI Tourist Agency Fact Sheets – activities". Lord Howe Island Tourism Association. Archived from the original on 3 May 2009. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- "LHI Tourist Agency Fact Sheets – SCUBA diving". Lord Howe Island Tourism Association. Archived from the original on 2 September 2011. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- "LHI Tourist Agency Fact Sheets – general activities". Lord Howe Island Tourism Association. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- "LHI Tourist Agency Fact Sheets – marine activities". Lord Howe Island Tourism Association. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- "LHI Tourist Agency Fact Sheets – walking". Lord Howe Island Tourism Association. Archived from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- "Permanent Park Preserve and Walking Tracks" (PDF). LHI Tourist Agency Fact Sheets. Lord Howe Island Tourism Association. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- Rabone 1972, p. 18

- "Mt Gower, Lord Howe Island". New South Wales Government Destination NSW. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- Hutton 1986, pp. 81–84

- Six-Legged Giant Finds Secret Hideaway, Hides For 80 Years

- McDougall, Ian; Embleton, B. J. J.; Stone, D. B. (April 1981). "Origin and evolution of Lord Howe Island, Southwest Pacific Ocean". Journal of the Geological Society of Australia. 28 (1–2): 155–176. Bibcode:1981AuJES..28..155M. doi:10.1080/00167618108729154. ISSN 0016-7614.

- Hutton 1986, p. 7

- Van Der Linden, W. J. M. (1969). "Extinct mid-ocean ridges in the Tasman sea and in the Western Pacific". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 6 (6): 483–490. Bibcode:1969E&PSL...6..483V. doi:10.1016/0012-821X(69)90120-4.

- Wallis & Trewick 2009, p. 3548

- Hutton 1986, pp. 7–14

- Hutton 2009, p. 30

- "Volcanic Geology". Lord Howe Island Museum. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- "Lord Howe Island". Blueswami. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- Etheridge 1889, pp. 112–113

- Hutton & Harrison 2004, p. 11

- "Sedimentary Geology". Lord Howe Island Museum. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- Green 1986, p. 15

- Clarke, Sarah (24 March 2010). "Bleaching leaves Lord Howe reef 'on knife edge'". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- See McDougall 1981

- Gavrilets 2007, pp. 2910–2921

- "Climate of Lord Howe Island". Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- "The Lord Howe Island Marine Park (Commonwealth Waters) Management Plan" (PDF). Canberra: Environment Australia. 2001. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 November 2011.

- "Weather and Forecast". Lord Howe Island Tours. 2011. Archived from the original on 31 March 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- "Climate statistics for Australian locations". Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- Green 1994, pp. 14–15

- "Climate of Lord Howe Island". Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- "Water Temperature - Lord Howe, Australia".

- "Climate statistics for Australian locations". Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology. August 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- "Ecoregions". World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- Hutton 1986, p. 35

- "Burke's Backyard – Kentia Palms". CTC Productions. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- Lord Howe Island: 1788–1988 (PDF). National Library of Australia. 1989. ISBN 978-0-7316-3090-5. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- SeeHutton 1986

- Green 1994, p. 2

- Green 1994, p. 1

- Pickard 1983b, pp. 133–236

- Hutton 2010a, p. 4

- Hutton 2010, p. 37

- "Lord Howe Island Plant Life" (PDF). Lord Howe Island Tourism Association. 2007. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- Barton, Greg (October–November 2007). "Ten ridiculously amazing things to do on Lord Howe Island" (PDF). Australian Traveller: 98. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 April 2013.

- Nichols 206, pp. 98–105

- Nichols 2006, p. 98

- Hutton 1986, p. 15

- Hutton 2010b, p. 2

- BirdLife International. (2011). Important Bird Areas factsheet: Lord Howe Island Permanent Park Preserve. Downloaded from "BirdLife | Partnership for nature and people". Archived from the original on 30 June 2007. Retrieved 2012-12-10. on 2011-12-24.

- Hutton 1990, p. 84

- Hutton 1990, p. 68

- Hutton 1990, p. 70

- Hutton 1990, p. 72

- Hutton 1990, p. 74

- Hutton 1990, p. 80

- Hutton 1990, p. 82

- Hutton 1990, p. 92

- Hutton 1990, pp. 92–94

- Hutton 1990

- Nichols 2006, p. 121

- Daniel & Williams 1984

- Recher & Clark 1974

- "David Attenborough's rare sighting". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- "Dryococelus australis in Species Profile and Threats Database". Canberra: Australian Government Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. 2011. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- Krulwich, Robert (29 February 2012). "Six-Legged Giant Finds Secret Hideaway, Hides For 80 Years". National Public Radio.

- "Lord Howe stag beetle (Lamprima insularis)". Lord Howe Island Museum. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- Hutton & Harrison 2004, pp. 11–12

- Hutton 1986, p. 73

- Veron & Done 1979

- See Harriott, Harrison & Banks 1995

- See Coleman 2001

- The Commonwealth of Australia. 2002. Lord Howe Island Marine Park (Commonwealth Waters) - MANAGEMENT PLAN. Retrieved on December 18. 2014

- Berzin A.; Ivashchenko V.Y.; Clapham J.P.; Brownell L.R. Jr. (2008). "The Truth About Soviet Whaling: A Memoir" (PDF). DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- Daphne D.. 2006. Lord Howe Island Rising. Frenchs Forest, NSW: Tower Books. ISBN 0-646-45419-6. Retrieved on December 18. 2014

- Richards R.. 2009. Past and present distributions of southern right whales (Eubalaena australis). New Zealand Journal of Zoology. Vol. 36: 447-459. 1175-8821 (Online); 0301-4223 (Print)/09/3604–0447. The Royal Society of New Zealand. Retrieved on December 18. 2014

- See Pickard 1983a

- Hutton, Parkes & Sinclair 2007, p. 22

- Hutton, Parkes & Sinclair 2007, p. 24

- See Recher & Clark 1974

- Lord Howe Island Permanent Park Preserve Plan of Management (PDF). Lord Howe Island Board. 2010. ISBN 978-1-74293-082-4. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

- "Visitors guide – Lord Howe Island Marine Park" (PDF). New South Wales Government Marine Park Authority. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- Hutton & Harrison 2004, p. 6

- Nichols 2006, p. 118

- Nichols 2006, pp. 118–119

- Nichols 2006, p. 119

- "Species factsheet: Gallirallus sylvestris". BirdLife International. 2011. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- "Background". Crofton Weed biological control. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- "CAWS · The Council of Australasian Weed Societies Inc". caws.org.nz. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- Hutton 1986, p. 40

- Nichols 2006, pp. 122–123

- Hutton 2010c, p. 5

- Anonymous (21 June 2015). "Pest Animal Control". www.lhib.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- "Friends of Lord Howe Island Newsletter" (PDF). Friends of Lord Howe Island. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- Silmalis, Linda (15 July 2012). "Bombs to fight the killer rats on Lord Howe Island". Courier Mail. News Queensland. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- Slezak, Michael (8 February 2016). "Trouble in paradise: Lord Howe Island divided over plan to exterminate rats". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- Siossian, Emma; Wyllie, Fiona (18 January 2020). "Endangered Lord Howe Island woodhens successfully released back into the wild". ABC News. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- Flannery, Tim (2006). The Weather Makers - The History and Future Impact of Climate Change. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9921-1.

- See Jones 2004

- Towards Global Artificial Photosynthesis Conference, Lord Howe Island 2011 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 2016-04-07.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Australian Journal of Chemistry Volume 65 Number 6 2012 'Artificial Photosynthesis: Energy, Nanochemistry, and Governance' http://www.publish.csiro.au/nid/52/issue/5915.htm

- Davies, Anne (18 September 2019). "Josh Frydenberg overruled department to block Lord Howe Island wind turbines". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

Bibliography

- Allen, Gerald R.; et al. (1976). "Annotated checklist of the fishes of Lord Howe Island". Records of the Australian Museum. 30 (15): 365–454. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.30.1976.287.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coleman, Neville (2001). 1001 Nudibranchs – Catalogue of Indo-Pacific Sea Slugs. Springwood. ISBN 978-0-947325-25-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coleman, Neville (2002). Lord Howe Island Marine Park: Sea Shore to Sea Floor: World Heritage Wildlife Guide. Rochedale: Neville Coleman's Underwater Geographic. ISBN 978-0-947325-27-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Daniel, M.J.; Williams, G.R. (1984). "A survey of the distribution, seasonal activity and roost sites of New Zealand bats" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Ecology. 7: 9–25.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Etheridge, Robert (1889). "Lord Howe Island its zoology, geology, and physical characters. No. 5. The physical and geological structure of Lord Howe Island" (PDF). Australian Museum Memoir. 2 (5): 99–126. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1967.2.1889.483. ISSN 0067-1967.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Flannery, Tim (2006). The Weather Makers – The History and Future Impact of Climate Change. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9921-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gaffney, Eugene S. (1975). "A phylogeny and classification of the higher categories of turtles. (article 4)". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 155 (5): 389–436. hdl:2246/614.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gavrilets, Sergei; Vose, Arron (2007). "Case studies and mathematical models of ecological speciation. 2. Palms on an oceanic island". Molecular Ecology. 16 (14): 2910–2921. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294x.2007.03304.x. PMID 17614906.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Green, Peter S. (1994). "Lord Howe Island". In Orchard, Anthony E (ed.). Flora of Australia. Volume 49, Oceanic Islands 1. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. ISBN 0-644-29385-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harriott, V.J.; Harrison, P.L.; Banks, S.A. (1995). "The coral communities of Lord Howe Island". Marine and Freshwater Research. 46 (2): 457–465. doi:10.1071/mf9950457.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hill, E S (1870). "Lord Howe Island – Official visit by the Water Police Magistrate and the Director of the Botanic Gardens, Sydney; together with a description of the island". Votes & Proc. Legislative Assembly New South Wales 1870: 635–654.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hutton, Ian (1986). Lord Howe Island. Australian Capital Territory: Conservation Press. ISBN 978-0-908198-40-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hutton, Ian (1990). Birds of Lord Howe Island – Past and Present. Ian Hutton. ISBN 978-0-646-02638-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hutton, Ian (1998). The Australian Geographic Book of Lord Howe Island. Australian Geographic. ISBN 978-1-876276-27-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hutton, Ian; Parkes, John P. & Sinclair, Anthony R. E. (2007), "Reassembling island ecosystems: the case of Lord Howe Island" (PDF), Animal Conservation, 10 (22): 22–29, doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2006.00077.x, retrieved 25 June 2011

- Hutton, Ian (2009). A Guide to World Heritage Lord Howe Island. Lord Howe Island Museum.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hutton, Ian (2010a). A field guide to the ferns of Lord Howe Island. Lord Howe Island: Ian Hutton. ISBN 978-0-9581286-7-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hutton, Ian (2010b). A field guide to the birds of Lord Howe Island. Lord Howe Island: Ian Hutton. ISBN 978-0-9581286-2-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hutton, Ian (2010c). A field guide to the plants of Lord Howe Island. Lord Howe Island: Ian Hutton. ISBN 978-0-9581286-1-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hutton, Ian; Harrison, Peter (2004). A field guide to the marine life of Lord Howe Island. Lord Howe Island: Ian Hutton. ISBN 978-0-9581286-3-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, R N (2004). "Managing Climate Change Risks". In Agrawala, S.; Corfee-Morlot, J. (eds.). The Benefits of Climate Change Policies: Analytical and Framework Issues, OECD cited in the CSIRO's Climate Change Impacts on Australia and the Benefits of Early Action to Reduce Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions". Paris. pp. 249–298.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McDougall, I; Embleton, B J; Stone, D B (1981). "Origin and evolution of Lord Howe Island, Southwest Pacific Ocean". Journal of the Geological Association of Australia. 28 (1–2): 155–176. Bibcode:1981AuJES..28..155M. doi:10.1080/00167618108729154.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mueller, Ferdinand J.H. von (1875). Fragmenta Phytographiae Australiae 9. Melbourne: Government Printer. pp. 76–79.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- National Library of Australia (1989). Lord Howe Island: 1788–1988. From Antipodean Isolation to World Heritage. A Bicentennial Publication (PDF). National Library of Australia. ISBN 978-0-7316-3090-5. Retrieved 24 January 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nichols, Daphne (2006). Lord Howe Island Rising. Frenchs Forest, NSW: Tower Books. ISBN 978-0-646-45419-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pickard, John (1983a). "Rare or threatened vascular plants of Lord Howe Island". Biological Conservation. 27 (2): 125–139. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(83)90084-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pickard, John (1983b). "Vegetation of Lord Howe Island". Cunninghamia. 17: 133–266.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pickard, John (1984). "Exotic plants of Lord Howe Island: distribution in space and time, 1853–1981". Journal of Biogeography. 11 (3): 181–208. doi:10.2307/2844639. JSTOR 2844639.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rabone, Harold R (1972). Lord Howe Island: Its discovery and early associations 1788 to 1888. Sydney: Australis.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Recher, Harry F; Clark, Stephen S (1974). Environmental survey of Lord Howe Island : a report to the Lord Howe Island Board / edited by Harry F. Recher and Stephen S. Clark Lord Howe Island Board (N.S.W.). Australian Museum: Dept. of Environmental Studies.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)Recher, H. F.; Clark, S. S. (1974). "A biological survey of Lord Howe Island with recommendations for the conservation of the island's wildlife". Biological Conservation. 6 (4): 263. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(74)90005-6.

- Starbuck, Alexander (1878). History of the American Whaling Fishery from its Earliest Inception to the Year 1876. Waltham, Massachusetts: author.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Veron, John E; Done, T J (1979). "Corals and coral communities of Lord Howe Island". Australian Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 30 (2): 203–236. doi:10.1071/mf9790203.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wallis, G.P.; Trewick, Steve A. (2009). "New Zealand phylogeography: evolution on a small continent". Molecular Ecology. 18 (17): 3548–80. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04294.x. PMID 19674312.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilson, J. Bowie (John Bowie) (1882). Report on the present state and future prospects of Lord Howe Island. T. Richards, Govt. Printer. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

Attribution

![]()

Further reading

- Lindsay, MJ; Patterson, HM; Swearer, SE (2008). "Habitat as a surrogate measure of reef fish diversity in the zoning of the Lord Howe Island Marine Park, Australia". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 353: 265–273. Bibcode:2008MEPS..353..265L. doi:10.3354/meps07155.

- O’Hara, Timothy (2008). Bioregionalisation of the waters around Lord Howe and Norfolk Islands using brittle stars (Echinodermata: Ophiuroidea). ISBN 978-0-642-55462-8.