Kiril Peychinovich

Kiril Peychinovich or Kiril Pejčinoviḱ (Bulgarian: Кирил Пейчинович, Macedonian: Кирил Пејчиновиќ, Church Slavonic: Күриллъ Пейчиновићь (c. 1770 – 7 March 1865) was a Bulgarian cleric, writer and enlightener, one of the first supporters of the use of modern Bulgarian in literature (as opposed to Church Slavonic), and one of the early figures of the Bulgarian National Revival.[1][2][3]

Kiril Peychinovich Кирил Пейчинович Kiril Pejčinoviḱ Кирил Пејчиновиќ | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Kiril Peychinovich | |

| Born | c. 1771 Tearce, Ottoman Empire (present-day North Macedonia) |

| Died | March 7, 1845 Lešok, Ottoman Empire (present-day North Macedonia) |

| Pen name | "Tetoec" |

| Occupation | Cleric and writer |

| Genre | Religion |

| Notable works | Ogledalo and Utešenie Grešnim |

Although he thought of his language as Bulgarian,[4] and regarded as his homeland Lower Moesia, i.e. Bulgaria,[5][6] according to the post-WWII Macedonian historiography,[7][8][9] he was an ethnic Macedonian.[10][11][12] In modern-day North Macedonia, Peychinovich is considered one of the earliest contributors to modern Macedonian literature,[13][14][15] since most of his works were written in his native Tetovo dialect.

Biography

Early life and Mount Athos

Peychinovich was born in the large Polog village of Tearce (Теарце) in present-day North Macedonia (then part of the Ottoman Empire). His secular name is unknown. According to his tombstone, he received his primary education in the village of Lešok (Лешок). Probably he later studied at the Monastery of St. John Bigorski near Debar. Kiril's father, Peychin, sold his property in Tearce and, together with his brother and his son, moved to the monastery of Hilandar in Mount Athos where the three became monks. Peychin accepted the name Pimen, his brother — Dalmant, and his son — Kiril (Cyril). Later Kiril returned to Tetovo from there set out for the Kičevo Monastery of the Holy Immaculate Theotokos, where he became a hieromonk.

Hegumen of Marko's Monastery

Since 1801 Peychinovich was the hegumen of Marko's Monastery of Saint Demetrius near Skopje. Located in the region of Torbešija (Торбешия or Торбешија) along the valley of the Markova Reka (Marko's River) among Pomak, Turkish and Albanian villages, the monastery was in a miserable condition before Peychinovich's arrival. Almost all buildings except for the primary church had been destroyed. Through the course of 17 years until 1798 father Kiril made serious efforts to revive the monastery, paying particular attention to the reconstruction and expansion of the monastical library.

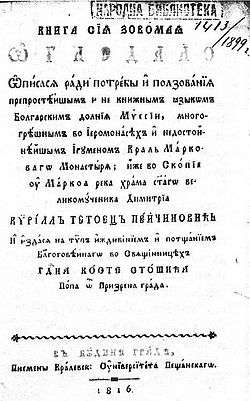

In Marko's Monastery Kiril Peychinovich compiled one of his best-known works, Kniga Siya Zovomaya Ogledalo, printed in 1816 in Budapest.

Hegumen of the Lešok Monastery

It is not known why father Kiril left Marko's Monastery, but according to the legend, a conflict between him and the Greek metropolitan of Skopje was the reason for his departure. In 1818 Peychinovich once again travelled to Mount Athos to see his father and uncle, and then became hegumen of the Monastery of Saint Athanasius (destroyed in 1710 by Janissaries) near the Polog village of Lešok in the proximity of his native Tearce. With the aid of the local Bulgarians Kiril restored the Lešok Monastery, which had been abandoned for 100 years. Kiril devoted himself to a considerable amount of preacher's, literary and educational work. He opened a school and tried to establish a printing press, convinced of the printed book's importance. Father Kiril later helped Teodosiy Sinaitski (Теодосий Синаитски) restore his printing press in Thessaloniki which had been burnt down in 1839. In 1840 Theodosius issued Peychinovich's second book, Kniga Glagolemaya Uteshenie Greshnim. Father Kiril Peychinovich died on 12 March 1845 in the Lešok Monastery and was buried in the churchyard. In 1934 the village of Burumli in Ruse Province, Bulgaria was renamed Peychinovo in honour of father Kiril.

Works

Kiril Peychinovich is the author of three books, two printed and one manuscript (Zhitie i Sluzhba na Tsar Lazar), all three devoted to religion.

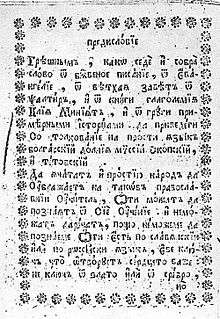

Ogledalo

Ogledalo ("Mirror") has a form of a sermon with a liturgical-ascetical character. It is an original work of the Author, inspired by the Kolivari (also called Filokalist) movement on Mount Athos, that was fighting for a liturgical renewal within the Orthodox Church on the Balkans. For this aim the Kolivari were using the spoken language of the people, according to the region where they were translating and writing. The most important topics of the work are: the significance of the liturgical life, the preparation for the Holy Communion, the regularly receiving of the Holy Communion. Especially important is his argumentation against the superstition and on the importance of the individual ascetic life and the participation in the liturgical life of the Church. In addition, a collection of Christian prayers and instructions, some of which written by father Kiril himself are added on the end of the work.[16][17][18]

According to the book's title page, it was written in the 'most common and illiterary Bulgarian language of Lower Moesia' ('препростейшим и некнижним язиком Болгарским долния Мисии'). It was printed in 1816 in Budapest.

Utesheniе Greshnim

Peychinovich's second book, Utesheniе Greshnim ("Solace of the sinner"), much like his first, is a Christian collection of instructions — including advice on how weddings should be organized and how those who had sinned should be consoled, as well as a number of instructive tales.

Utesheniе Greshnim was ready to be printed in 1831, as specified by father Kiril in a note in the original manuscript. It was sent to Belgrade to be printed, but this did not happen for an unknown reason, and it had to be printed in Thessaloniki nine years later, in 1840, by Theodosius of Sinai. During the printing Theodosius substituted Peychinovich's original introduction with his own one, but still preserved the text that referred to the language of the work as the 'common Bulgarian language of Lower Moesia, of Skopje and Tetovo' (простїй Ѧзыкъ болгарский долнїѦ Мүссїи Скопсский и Тетовский).

Poems

In 1835 Peychinovich composed an epitaph for himself in verse.

Теарце му негово рождение

Пречиста и Хилендар пострижение

Лешок му е негоо воспитание

Под плочава негоо почивание

От негово свое отшествие

До Христово второ пришествие

Молит вас бракя негои любимия

Хотящия прочитати сия

Да речете Бог да би го простил

Зере у гроб цръвите ги гостил

Овде лежи Кирилово тело

У манастир и у Лешок село

Да Бог за доброе дело.

References and notes

- James Franklin Clarke, Dennis P. Hupchick - "The pen and the sword: studies in Bulgarian history", Columbia University Press, 1988, ISBN 0-88033-149-6, page. 221 (...Peichinovich of Tetovo, Macedonia, author of one of the first Bulgarian books...)

- Developing cultural identity in the Balkans: convergence vs divergence, Raymond Detrez, Pieter Plas, Peter Lang, 2005, ISBN 90-5201-297-0, p. 178.

- Йоаким Кърчовски и Кирил Пейчинович. Техните заслуги за развитието на печатната книга и за утвърждаването на простонародния език в литературата. “Люлка на старата и новата българска писменост. Академик Емил Георгиев (Държавно издателство Народна просвета, София 1980)

- Kiril called his native dialect: most common and illiterate Bulgarian language. He mentioned on the title page of his book Ogledalo (Mirror, 1816), published in Budapest, that the book was written in simple Bulgarian, as opposed to the literary, archaic, version of Church Slavonic, because of the need and the use in the simplest and not literary Bulgarian language of Lower Moesia. For more see: Sampimon, Janette. Becoming Bulgarian: the articulation of Bulgarian identity in the nineteenth century in its international context: an intellectual history, Pegasus, Amsterdam 2006, ISBN 90-6143-311-8, pp. 119, 222;

- In Ottoman times the names "Lower Bulgaria" and "Lower Moesia" were used by the local Slavs to designate most of the territory of today's geographical region of Macedonia and the names Bulgaria and Moesia were identified as identical. For more see: Drezov K. (1999) Macedonian identity: an overview of the major claims; p. 50, in: Pettifer J. (eds) The New Macedonian Question. St Antony’s Series. Palgrave Macmillan, London, ISBN 0230535798.

- The Ottoman conquest of the Balkans found regional names, well established among the local population, which had formed as a result of ethnic changes and the political state of affairs in the Middle Ages. The name Bulgaria was retained along with that of Lower Land, Lower Bulgaria or Lower Moesia, respectively, chiefly for the western territories, i.e. Ancient Macedonia. For more see: Petar Koledarov, Ethnical and Political Preconditions for Regional Names in the Central and Eastern Parts of the Balkan Peninsula; in An Historical Geography of the Balkans, edited by Francis W. Carter, Academic Press, 1977; p. 293-317.

- The origins of the official Macedonian national narrative are to be sought in the establishment in 1944 of the Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. This open acknowledgement of the Macedonian national identity led to the creation of revisionist historiography whose goal has been to affirm the existence of the Macedonian nation through history. Macedonian historiography is revising a considerable part of ancient, medieval, and modern histories of the Balkans. Its goal is to claim for the Macedonian peoples a considerable part of what the Greeks consider Greek history and the Bulgarians Bulgarian history. The claim is that most of the Slavic population of Macedonia in the 19th and first half of the 20th century was ethnic Macedonian. For more see: Victor Roudometof, Collective Memory, National Identity, and Ethnic Conflict: Greece, Bulgaria, and the Macedonian Question, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002, ISBN 0275976483, p. 58; Victor Roudometof, Nationalism and Identity Politics in the Balkans: Greece and the Macedonian Question in Journal of Modern Greek Studies 14.2 (1996) 253-301.

- Yugoslav Communists recognized the existence of a Macedonian nationality during WWII to quiet fears of the Macedonian population that a communist Yugoslavia would continue to follow the former Yugoslav policy of forced Serbianization. Hence, for them to recognize the inhabitants of Macedonia as Bulgarians would be tantamount to admitting that they should be part of the Bulgarian state. For that, the Yugoslav Communists were most anxious to mould Macedonian history to fit their conception of Macedonian consciousness. The treatment of Macedonian history in Communist Yugoslavia had the same primary goal as the creation of the Macedonian language: to de-Bulgarize the Macedonian Slavs and to create a separate national consciousness that would inspire identification with Yugoslavia. For more see: Stephen E. Palmer, Robert R. King, Yugoslav Communism and the Macedonian question, Archon Books, 1971, ISBN 0208008217, Chapter 9: The encouragement of Macedonian culture.

- "At any rate, the beginning of the active national-historical direction with the historical “masterpieces”, which was for the first time possible in 1944, developed in Macedonia much harder than was the case with the creation of the neighbouring nations in the 19th century. These neighbours almost completely "plundered" the historical events and characters from the land, and there was only debris left for the belated nation. A consequence of this was that first that parts of the “plundered history” were returned, and a second was that an attempt was made to make the debris become a fundamental part of an autochthonous history. This resulted in a long phase of experimenting and revising, during which the influence of non-scientific instances increased. This specific link of politics with historiography... was that this was a case of mutual dependence, i.e. influence between politics and historical science, where historians do not simply have the role of registrars obedient to orders. For their significant political influence, they had to pay the price for the rigidity of the science... There is no similar case of mutual dependence of historiography and politics on such a level in Eastern or Southeast Europe." For more see: Stefan Trobest, “Historical Politics and Histrocial ‘Masterpieces’ in Macedonia before and after 1991”, New Balkan Politics, 6 (2003).

- Because in many documents of 19th and early 20th century period, the local Slavic population is not referred to as "Macedonian" but as "Bulgarian", Macedonian historians argue that it was Macedonian, regardless of what is written in the records. For more see: Ulf Brunnbauer, “Serving the Nation: Historiography in the Republic of Macedonia (FYROM) after Socialism“, Historien, Vol. 4 (2003-4), pp. 161-182.

- Numerous prominent activists with pro-Bulgarian sentiments from the 19th and early 20th centuries are described in Macedonian textbooks as ethnic Macedonians. Macedonian researchers claim that "Bulgarian" at that time was a term, not related to any ethnicity, but was used as a synonym for "Slavic", "Christian" or "peasant". Chris Kostov, Contested Ethnic Identity: The Case of Macedonian Immigrants in Toronto, 1900-1996, Peter Lang, 2010, ISBN 3034301960, p. 92.

- Until the 20th century, both outside observers and those Bulgarian and Macedonian Slavs who had clear ethnic consciousness, believed that their group, which is now divided into two separate nationalities, comprised a single people: the Bulgarians. Thus the reader should ignore references to ethnic Macedonians in the Middle Ages and Ottoman era, which appear in some modern works. For more see: John Van Antwerp Fine, The Early Medieval Balkans: a critical survey from the sixth to the late twelfth century, University of Michigan Press, 1994, ISBN 0472082604 p. 37.

- Виктор Фридман, "Модерниот македонски стандарден jазик и неговата врска со модерниот македонски идентитет", "Македонското прашање", "Евро-Балкан Прес", Скопје, 2003

- Блаже Конески, "За македонскиот литературен jазик", "Култура", Скопје, 1967

- Teodosij Sinaitski, Konstantin Kajdamov, Dojran, 1994

- Милан Ѓорѓевиќ, Агиоритското просветителство на преподобен Кирил Пејчиновиќ I (The Hagioretic Enlightenment of Venerable Kiril Pejcinovic), study, in: “Премин”, бр. 41-42, Скопје 2007

- Милан Ѓорѓевиќ, Агиоритското просветителство на преподобен Кирил Пејчиновиќ II (The Hagioretic Enlightenment of Venerable Kiril Pejcinovic), study, in: “Премин”, бр. 43-44, Скопје 2007

- Милан Ѓорѓевиќ, Верска VS граѓанска просвета. Прилог кон разрешувањето на еден научен парадокс, in: Православна Светлина, бр. 12, Јануар 2010

External links

- ""Книга сия зовомая Огледало", Будапеща, 1816 година - Ogledalo (Mirror) online

- Pejčinoviḱ's Biography and work (in Macedonian)

- The life of Kiril Pejčinoviḱ (in Macedonian)

- Biography (in English)

- Kiril Pejčinoviḱ (in English)