Hunger in the United States

Hunger in the United States of America affects millions of Americans, including some who are middle class, or who are in households where all adults are in work.

_Donya_Craig%2C_right%2C_serves_chicken_to_a_patron_at_Norma_Todd's_Lunch_Brea.jpg)

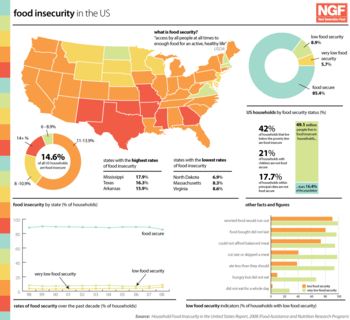

In 2018, about 11.1% of American households were food insecure. Surveys have consistently found much higher levels of food insecurity for students, with a 2019 study finding that over 40% of US undergraduate students experienced food insecurity. Following the 2020 COVID-19 outbreak, indicators suggested the prevalence of food insecurity for US households has approximately doubled, with an especially sharp rise for households with young children. [1][2][3]

The United States produces far more food than it needs for domestic consumption—hunger within the U.S. is caused by some Americans having insufficient money to buy food for themselves or their families. Additional causes of hunger and food insecurity include neighborhood deprivation and agricultural policy.[4][5] Hunger is addressed by a mix of public and private food aid provision. Public interventions include changes to agricultural policy, the construction of supermarkets in underserved neighborhoods, investment in transportation infrastructure, and the development of community gardens.[6][7][8][9] Private aid is provided by food pantries, soup kitchens, food banks, and food rescue organizations.[10][11][12]

In the later half of the twentieth century, other advanced economies in Europe and Asia began to overtake the U.S. in terms of reducing hunger among their own populations. In 2011, a report presented in the New York Times found that among 20 economies recognized as advanced by the International Monetary Fund and for which comparative rankings for food security were available, the U.S. was joint worst.[13] Nonetheless, in March 2013, the Global Food Security Index commissioned by DuPont, ranked the U.S. number one for food affordability and overall food security.[14]

Food insecurity

Food insecurity is defined at a household level, of not having adequate food for any household member due to finances. The step beyond this is very low food security, which is having six (for families without children) to eight (for families with children) or more food insecure conditions in the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food Security Supplement Survey. To be very low food secure means members of the household disrupt their food intake due to financial reasons.[15]

These conditions are: worrying about running out of food, that food bought doesn’t last, a lack of a balanced diet, adults cutting down portion sizes or out meals entirely, eating less than what they felt they should, being hungry and not eating, unintended weight loss, not eating for whole days (repeatedly), due to financial reasons.[16]

Food Insecurity is closely related to poverty but is not mutually exclusive. Food insecurity does not exist in isolation and is just one individual aspect in the multiple factors of social determinants regarding health [17]

Hunger vs. food insecurity

According to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), food insecurity is "a household-level economic and social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food." [18] Hunger, on the other hand, is defined as "an individual-level physiological condition that may result from food insecurity." [18] The USDA has also created a language to describe various severities of food insecurity.[18] High food security occurs when there are "no reported indications of food-access problems or limitations." [18] Marginal food security occurs when there are one to two reported indications of "food-access problems or limitations" such as anxiety over food shortages in the household but no observable changes in food intake or dietary patterns.[18] Low food security, previously called food insecurity without hunger, occurs when individuals experience a decrease in the "quality, variety, or desirability of diet" but do not exhibit reduced food intake.[18] Very low food security, previously called food insecurity with hunger, is characterized by "multiple indications of disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake." [18]

Prevalence of food insecurity in the United States

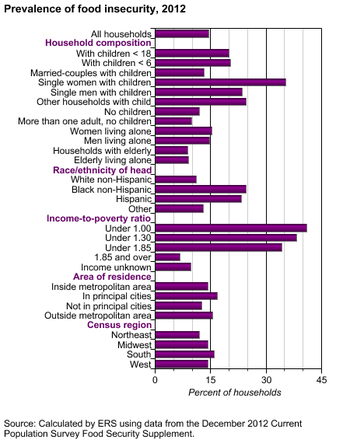

Research by the USDA found that 11.1% of American households were food insecure during at least some of 2018, with 4.3% suffering from "very low food security".[19] Breaking that down to 14.3 million households that experienced food insecurity.[20] Estimating that 37.2 million people living in food-insecure households, and experienced food insecurity in 2018.[21] Of these 37.2 million people approximately six million children were living in food insecure households and around a half million children experience very low food security. To be experiencing very low food insecurity, demonstrates modifying the eating norms due to financial struggles in ascertaining food. [22]

A survey took for Brookings in late April 2020 found indications that following the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of US households experiencing food insecurity had approximately doubled. For households with young children, indicators had suggested food insecurity may have reached about 40%, close to four times the prevalence in 2018, or triple what was seen for the previous peak that occurred in 2008, during the financial crisis of 2007–08.[3] [23]

Causes

Hunger and poverty

Hunger in the United States is caused by a complex combination of factors. There is not a single cause attributed to hunger and there is much debate over who or what is responsible for the prevalence of hunger in the United States. However, researchers most commonly focus on the link between hunger and poverty. The federal poverty level is defined as "the minimum amount of income that a household needs to be able to afford housing, food, and other basic necessities."[24] As of 2014, the federal poverty level for a family of four was 23,850 dollars [25]

Based on her research on poverty, Pennsylvania State University economic geographer Amy Glasmeier claims that when individuals live at, slightly above, or below the poverty line, unexpected expenses contribute to individuals reducing their food intake.[26] Medical emergencies have a significant impact on poor families due to the high cost of medical care and hospital visits. Also, urgent car repairs reduce a family's ability to provide food, since the issue must be addressed in order to allow individuals to travel to and from work.[26] Although income cannot be labeled as the sole cause of hunger, it plays a key role in determining if people possess the means to provide basic needs to themselves and their family.

The loss of a job reflects a core issue that contributes to hunger - employment insecurity.[26] People who live in areas with higher unemployment rates and who have a minimal or very low amount of liquid assets are shown to be more likely to experience hunger or food insecurity. The complex interactions between a person's job status, income and benefits, and the number of dependents they must provide for, influence the impact of hunger on a family.[27] For example, food insecurity often increases with the number of additional children in the household due to the negative impact on wage labor hours and an increase in the household's overall food needs.[28]

Despite research on the correlation between poverty and hunger, comparison of data from the December Supplement of the 2009 Current Population Survey illustrated that poverty is not a direct causation of hunger. Of all household incomes near the federal poverty line, 65% were identified as food secure while 20% of households above the poverty line with an income-to-poverty ratio of approximately two were labeled as food insecure.[29] The income-to-poverty ratio is a common measure used when analyzing poverty. In this particular case, it means that these households' total family income was approximately twice that of the federal poverty line for their specific family size.[30] As this data illustrates, the factors which contribute to hunger are interrelated and complex.

Neighborhood deprivation

An additional contributor to hunger and food insecurity in the U.S.A is neighborhood deprivation.[4] According to the Health & Place Journal, neighborhood deprivation is the tendency for low-income, minority neighborhoods to have greater exposure to unhealthy tobacco and alcohol advertisements, a fewer number of pharmacies with fewer medications, and a scarcity of grocery stores offering healthy food options in comparison to small convenience stores and fast-food restaurants.[4] These neighborhoods are often referred to as "food deserts," as the lack of supermarkets prevents individuals from being able to access affordable and healthy food options.[4]

There are several theories that attempt to explain why food deserts form.[4] One theory proposes that the expansion of large chain supermarkets results in the closure of smaller-sized, independent neighborhood grocery stores.[4] Market competition thereby produces a void of healthy food retailers in low-income neighborhoods.[4]

Another theory suggests that in the period between 1970 and 1988, there was increasing economic segregation, with a large proportion of wealthy households moving from inner cities to more suburban areas.[4] As a result, the median income in the inner cities rapidly decreased, causing a substantial proportion of supermarkets in these areas to close.[4]

Furthermore, business owners and managers are often discouraged from establishing grocery stores in low-income neighborhoods due to reduced demand for low-skilled workers, low-wage competition from international markets, zoning laws, and inaccurate perceptions about these areas.[4]

Agricultural policy

Another cause of hunger is related to agricultural policy. Due to the heavy subsidization of crops such as corn and soybeans, healthy foods such as fruits and vegetables are produced in lesser abundance and generally cost more than highly processed, packaged goods.[5] Because unhealthful food items are readily available at much lower prices than fruits and vegetables, low-income populations often heavily rely on these foods for sustenance.[5] As a result, the poorest people in the United States are often simultaneously undernourished and overweight or obese.[5][6] This is because highly processed, packaged goods generally contain high amounts of calories in the form of fat and added sugars yet provide very limited amounts of essential micronutrients.[5] These foods are thus said to provide "empty calories." [5]

No right to food for US citizens

In 2017, the US Mission to International Organizations in Geneva explained,

"Domestically, the United States pursues policies that promote access to food, and it is our objective to achieve a world where everyone has adequate access to food, but we do not treat the right to food as an enforceable obligation."[31]

The US is not a signatory of Article 11 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, which recognizes "the fundamental right of everyone to be free from hunger," and has been adopted by 158 countries.[32] Activists note that "United States opposition to the right to adequate food and nutrition (RtFN) has endured through Democratic and Republican administrations."[33]

Holding the federal government responsible for ensuring the population is fed has been criticized as "nanny government."[32] The right to food in the US has been criticized as being "associated with un-American and socialist political systems", "too expensive", and as "not the American way, which is self-reliance."[32] Anti-hunger activists have countered that "It makes no political sense for the US to continue to argue that HRF [the human right to food] and other economic rights are “not our culture” when the US pressures other nations to accept and embrace universal civil-political rights that some argue are not their culture."[33]

Olivier De Schutter, former UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, notes that one difficulty in promoting a right to food in the United States is a "constitutional tradition that sees human rights as “negative” rights—rights against government—not “positive” rights that can be used to oblige government to take action to secure people’s livelihoods."[34]

The Constitution of the United States "does not contain provisions related to the right to adequate food," according to the FAO.[35][36]

Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed that a Second Bill of Rights was needed to ensure the right to food. The phrase "freedom from want" in Roosevelt's Four Freedoms has also been considered to encompass a right to food.[32]

A 2009 article in the American Journal of Public Health declared that "Adopting key elements of the human rights framework is the obvious next step in improving human nutrition and well-being."[37]

It characterizes current US domestic policy on hunger as being needs-based rather than rights-based, stating:

"The emphasis on charity for solving food insecurity and hunger is a “needs-based” approach to food. The needs-based approach assumes that people who lack access to food are passive recipients in need of direct assistance. Programs and policy efforts that use this approach tend to provide assistance without expectation of action from the recipient, without obligation and without legal protections."[37]

Because "there is no popularly conceived, comprehensive plan in the U.S. with measurable benchmarks to assess the success or failures of the present approach [to hunger]," it is difficult for the US public to hold "government actors accountable to progressively improving food and nutrition status."[33]

In 2014, the American Bar Association adopted a resolution urging the US government "to make the realization of a human right to adequate food a principal objective of U.S. domestic policy.”[38]

An August 2019 article explains that the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as the Food Stamp Program) only partially fulfills the criteria set out by a right to food.[39]

Jesse Jackson has stated that it was Martin Luther King's dream that all Americans would have a right to food.[40]

Impact of hunger

Children

In 2011 16.7 million children lived in food-insecure households, about 35% more than 2007 levels, though only 1.1% of U.S. children, 845,000, saw reduced food intake or disrupted eating patterns at some point during the year, and most cases were not chronic.[41]

Almost 16 million children lived in food-insecure households in 2012.[42] Schools throughout the country had 21 million children participate in a free or reduced lunch program and 11 million children participate in a free or reduced breakfast program. The extent of American youth facing hunger is clearly shown through the fact that 47% of SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) participants are under the age of 18.[42] The states with the lowest rate of food insecure children were North Dakota, Minnesota, Virginia, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts as of 2012.

In 2018 six million children experience food insecurity.[43] Feeding America estimates that around one in seven children or approximately 11 million, children experience hunger and do not know where they will get their next meal or when.[44] The wide breadth between these source's data could possibly be explain that food insecurity is not all-encompassing of hunger, and is only a solid predictor. 13.9% of households with children experience food insecurity with the number increasing for households having children under the age of six (14.3%).[44]

Children who experience hunger have an increase in both physical and psychological health problems. Although there is not a direct correlation between chronic illnesses and hunger among children, the overall health and development of children decreases with exposure to hunger and food insecurity.[45] Children are more likely to get ill and require a longer recovery period when they don't consume the necessary amount of nutrients. Additionally, children who consume a high amount of highly processed, packaged goods are more-likely to develop chronic diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease due to these food items containing a high amount of calories in the form of added sugars and fats.[29][5] In regards to academics, children who experience hunger perform worse in school on both mathematic and reading assessments. Children who consistently start the day with a nutritious breakfast have an average increase of 17.5% on their standardized math scores than children who regularly miss breakfast.[42]

Behavioral issues arise in both the school environment and in the children's ability to interact with peers of the same age. This is identified by both parental and teacher observations and assessments. Children are more likely to repeat a grade in elementary school and experience developmental impairments in areas like language and motor skills.[44]

Hunger takes a psychological toll on youth and negatively affects their mental health. Their lack of food contributes to the development of emotional problems and causes children to have visited with a psychiatrist more often than their sufficiently fed peers.[46] Research shows that hunger plays a role in late youth and young adult depression and suicidal ideation. It was identified as a factor in 5.6% of depression and suicidal ideation cases in a Canadian longitudinal study.[47]

College students

A growing body of literature suggests that food insecurity is an emerging concern in college students. Food insecurity prevalence was found to be 43.5% in a systematic review of food insecurity among US students in higher education.[2] This prevalence of food insecurity is over twice as high as that reported in United States national households.[48] Data have been collected to estimate prevalence both nationally as well as at specific institutions (two and four year colleges). For example, a Oregon university reported that 59% of their college students experienced food insecurity[48] where as in a correlational study conducted at the University of Hawaii at Manoa found that 21-24% of their undergraduate students were food-insecure or at risk of food insecurity.[49] Data from a large southwestern university show that 32% of college freshmen, who lived in residence halls, self-reported inconsistent access to food in the past month.

Studies have examined the demographics of students who may be more likely to be affected by food insecurity. It's been found that students of color are more likely to be affected by food insecurities. According to a correlational study examining the undergraduate student population from universities in Illinois, African American students were more likely to report being very-low food secure compared to other racial groups.[49] Similarly, the aforementioned study from the University of Hawaii at Manoa found that their undergraduate students, who identified as Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, Filipinos, and mixed-race, were more likely to be at increased risk of food insecurity compared to Japanese students. Being a first generation student is another demographic that has been related to increased risk of food insecurity.[50] Other demographics that have been found to increase risk of food insecurity in college students include receiving financial aid, being financially independent, and being employed.[51] Researchers have speculated that students who live at home with their family are less likely to be food insecure, due to spending less on housing expenditures.[49]

College students struggling with access to food are more likely to experience negative effects on their health and academics. As for mental health, according to a correlational study examining college freshmen living in residence halls from a large southwestern university, students who were food-insecure, were more likely to self-report higher levels of depression and anxiety, compared to food-secure students.[52] In terms of academics, college students with food insecurities were more likely to report grade point averages below a 3.0.[53]

Colleges have taken steps to address the issue of food insecurity on their campuses, though commentators have suggested more needs to be done. [54] [1] Researchers have suggested that college campuses examine available and accessible food-related resources to help alleviate students’ food insecurity.[51][50] In 2012, the College and University Food Bank Alliance (CUFBA) identified over 70 campuses where food pantries had been implemented or were under development.[55]

Elderly

Like children, the elderly population of the United States are vulnerable to the negative consequences of hunger. Senior citizens are considered to be of 65 years of age or older. In 2011, there was an increase of 0.9% in the number of seniors facing the threat of hunger from 2009. This resulted in a population of 8.8 million seniors who are facing this threat; however, a total of 1.9 million seniors were dealing with hunger at this time.[56] Seniors are particularly vulnerable to hunger and food insecurity largely due to their limited mobility.[57] They are less likely to own a car and drive, and when they live in communities that lack public transportation, it can be quite challenging to access adequate food.[57][58] Approximately 5.5 million senior citizens face hunger in the United States. This number has been steadily increasing since 2001 by 45%. Predictions believe that more than 8 million senior citizens will be suffering by 2050. Senior citizens are at an increased risk of food insecurity with many having fixed incomes and having to choose between health care and food. With most eligible seniors failing to enroll and receive food assistance such as SNAP. [59] The organization Meals on Wheels reports that Mississippi, New Mexico, Arkansas, and Texas are the states with the top rates of seniors facing the threat of hunger respectively.[60] Due to food insecurity and hunger, the elderly population experiences negative effects on their overall health and mental wellbeing. Not only are they more prone to reporting heart attacks, other cardiac conditions, and asthma, but food insecure seniors are also 60% more likely to develop depression.[61]

Gender

In a 2018 survey, there were findings displaying that gender impacts food insecurity. It found that single headed houses experience food insecurity at higher rates then the national average. Single headed households headed by women (14.2% for those living alone, and those with children 27.8%) had higher rates then male single-headed households (living alone:12.5% and those with children 15.9%) both with and without children.[20]

Ethnicity

Minority groups are affected by hunger to far greater extent than the Caucasian population in the United States. According to research conducted by Washington University in St. Louis on food insufficiency by race, 11.5% of Whites experience food insufficiency compared to 22.98% of African Americans, 16.67% of American Indians, and 26.66% of Hispanics when comparing each racial sample group.[62]

Feeding America reports that 29% of all Hispanic children and 38% of all African American children received emergency food assistance in 2010. White children received more than half the amount of emergency food assistance with 11% receiving aid. However, Hispanic household are less likely to have interaction with SNAP than other ethnic groups and received assistance from the program.[63]

Black

In the same survey during 2018 it displays a racial disparity between hunger, and food insecurity. For Blacks 21.2% experience food insecurity.[20] This becomes alarming when comparing poverty rates for Blacks to Whites with data displaying the highest groups to experience food insecurity is those that experience the most severe poverty (9% of which African-Americans live in deep poverty conditions).[20][64] In continuation and for further support "The 10 counties with the highest food insecurity rates in the nation are at least 60% African-American. Seven of the ten counties are in Mississippi".[64] This depicts the intersectionality of socio-economic and race to display the greatest food insecurity.

Hispanic/Latino

Another racial group that experiences great food insecurity is Hispanic/Latino population. Where one in six households struggle with hunger,[65] and approximately 1 in five children are at risk of hunger.[65] The food insecurity of the Latino population in the United States is 16.1% .[43]

Geographic regions

There are distinct differences between how hunger is experienced in the rural and urban settings. Rural counties experience high food insecurity rates twice as often as urban counties. It has been reported that approximately 3 million rural households are food insecure, which is equal to 15 percent of the total population of rural households.[66] This reflects the fact that 7.5 million people in rural regions live below the federal poverty line.[66] This poverty in rural communities is more commonly found in Southern states.[66] The prevalence of food insecurity is found to be highest in principal cities (13.2%), high in rural areas (12.7) and lowest in suburban and other metropolitan’ areas (non-principal cities) (8.9%). This could possibly display the poor infrastructure within rural and downtown areas in cities, where jobs maybe scare, or display a central reliance on a mode of transit which may come at additional cost.[67]

In addition, rural areas possess fewer grocery stores than urban regions with similar population density and geography. However, rural areas do have more supermarkets than similar urban areas.[68] Research has discovered that rural counties' poverty level and racial composition does not have a direct, significant association to supermarket access in the area. Urban areas by contrast have shown through countless studies that an increase in the African American population correlates to fewer supermarkets and the ones available require residents to travel a longer distance.[68] Despite these differences both city and rural areas experience a higher rate of hunger than suburban areas.[66]

Living in regions that are considered food deserts can prevent individuals from easily accessing healthy food markets and grocery stores due to lack of availability. Studies have shown that within these food deserts there exists distinct racial disparities. Compared to Caucasian neighborhoods, predominately African American neighborhoods have been reported to have half the amount of chain supermarkets available to residents.[69]

Despite racial differences, the vast majority of individuals living in food deserts struggle with transportation to food sources. Since these areas are low-income neighborhoods, many families may be unable to have the financial means to easily and regularly access supermarkets or grocery stores that tend to be located far from their home.[69] This acts as an additional obstacle individuals must face when trying to provide food for their family and prevent hunger.

Regionally, the food insecurity rate was highest in the South (12.0 percent).[67]

States

Regionally states experience different rates of food insecurity, and its severity. Rates of prevalence of food insecurity were highest in AL, AR, IN, KY, LA, MS, NC, NM, OH, OK, TX, and WV. These states have higher rates of very low food security in AL, AR, KS, LA, MS, NM, OH, OK, TX, and WV.[20]

Undocumented communities

Agriculture is a major industry in the United States, with California accounting for over 12% of the U.S. agriculture cash receipts.[70] Over half of agricultural workers in California, contributing to the state's agriculture economy and providing the nation with over half of all fruits and vegetables, are undocumented.[71] Despite undocumented laborers contributing to the agriculture industry, farm work and labor are among the lowest paid occupations in the U.S.[72] Many undocumented communities suffer from food insecurity due to low wages, forcing families to purchase economically viable unhealthy food.[73] Though existing food pantry and food stamp programs aid in reducing the amount of food insecure individuals, undocumented immigrants are ineligible for social service programs and studies have found that limited English acts as a barrier to food stamp program participation.[74] Due to a lack of education, encounters with government agents, language barriers, undocumented individuals pose higher rates of food insecurity and hunger when compared to legal citizens. The Trump administration is attempting to draft new stricter immigration policies;[75] undocumented individuals who fear being deported under the new policies, limit their interactions with government agencies, social service programs (e.g., food stamps), increasing their susceptibility to food insecurity.[74]

Food insecurity among undocumented communities can in some cases be traced to environmental injustices. Researchers argue that climate change increases food insecurity due to drought or floods and that the discourse must address issues on food security and on the food systems of the U.S.[76] Another example may be large populations of undocumented communities along the Central Valley of California.[77] Towns located across the Central Valley of CA exhibit some of the highest rates of air, water and pesticide pollution in the state.[78]

Consequences of hunger

Hunger

Hunger can manifest a multitude of physical symptoms and signs. Symptoms can that one may experience is tiredness, feelings of coldness, dry cracked skin, swelling, and dizziness. Signs maybe thinning of the face, pale flaky skin, low blood pressure, low pulse, low temperature and cold extremities. Additional signs denoting more extreme cases include vitamin deficient, osteocalcin, anemia, muscle tenderness, weakening of the muscular system, loss of sensation in extremities, heart failure, cracked lips diarrhea, and dementia. Server hunger can lead to the shrinking of the digestive system track, promote bacterial growth in the intestines, deterioration in the heart and kidney function, impair the immune system.[79]

Hunger for children

Hunger can lead to multiple health consequences, pre-birth development, low birth weights, higher frequency of illness and a delay in mental and physical development. This impairment may cause educational issues, which often can lead to children being held back a year in school.[80] Children experiencing hunger in the first three years of life are more likely to be hospitalized, experience higher rates of anemia and asthma and develop a weakened immune system, and develop chronic illnesses as an adult. Hunger in later stages of childhood can cause a delayed onset of puberty changing the rate of secretion of critically needed hormones.[81]

Hunger for elderly

Elderly people (people over the age of 60) are at an increased risk of experiencing hunger. Several reasons seniors are at a high risk of hunger and food insecurity is due to lack of mobility, pre-existing health issues, and potentially are at risk of living alone. This population has been experiencing increasingly higher rates of food-insecurity. One all too common occurrence for the elderly is choosing between food and medical care/insurance.[82]

Fighting hunger

Public sector hunger relief

As of 2012, the United States government spent about $50 billion annually on 10 programs, mostly administrated by the Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion, which in total deliver food assistance to one in five Americans.[10]

The largest and only universal[83] program is the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, formerly known as the food stamp program. In the 2012 fiscal year, $74.6 billion in food assistance was distributed.[84] As of December 2012, 47.8 million Americans were receiving on average $133.73 per month in food assistance.[84]

Despite efforts to increase uptake, an estimated 15 million eligible Americans are still not using the program. Historically, about 40 million Americans were using the program in 2010, while in 2001, 18 million were claiming food stamps. After cut backs to welfare in the early 1980s and late 1990s, private sector aid had begun to overtake public aid such as food stamps as the fastest growing form of food assistance, although the public sector provided much more aid in terms of volume.[10][85]

This changed in the early 21st century; the public sector's rate of increase in the amount of food aid dispensed again overtook the private sector's. President George W. Bush's administration undertook bipartisan efforts to increase the reach of the food stamp program, increasing its budget and reducing both the stigma associated with applying for aid and barriers imposed by red tape.[10] [86] Cuts in the food stamp programme came into force in November 2013, impacting an estimated 48 million poorer Americans, including 22 million children.[87] Commentators have stated hardship could worsen if a new Farm bill is passed: the version currently backed by the Democrats has a further $4 billion worth of cuts, while the version backed by Republicans would cut food stamps by $40 billion.[88][89]

Most other programs are targeted at particular types of citizen. The largest of these is the School Lunch program, which in 2010 helped feed 32 million children a day. The second largest is the School Breakfast Program, feeding 16 million children in 2010. The next largest is the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children, which provide food aid for about 9 million women and children in 2010.[10]

A program that is neither universal nor targeted is Emergency Food Assistance Program. This is a successor to the Federal Surplus Relief Corporation which used to distribute surplus farm production direct to poor people; now the program works in partnership with the private sector, by delivering the surplus produce to food banks and other civil society agencies.[10]

In 2010, the Obama administration initiated the Healthy Food Financing Initiative (HFFI) as a means of expanding access to healthy foods in low-income communities.[90] With over $400 million in funding from the Department of Health and Human Services, the Department of Agriculture and the Treasury Department, the initiative promoted interventions such as equipping already existing grocery stores and small retailers with more nutritious food options and investing in the development of new healthful food retailers in rural and urban food deserts.[90]

Agricultural policy

Another potential approach to mitigating hunger and food insecurity is modifying agricultural policy.[6] The implementation of policies that reduce the subsidization of crops such as corn and soybeans and increase subsidies for the production of fresh fruits and vegetables would effectively provide low-income populations with greater access to affordable and healthy foods.[6] This method is limited by the fact that the prices of animal-based products, oils, sugar, and related food items have dramatically decreased on the global scale in the past twenty to fifty years.[6] According to the Nutritional Review Journal, a reduction or removal of subsidies for the production of these foods will not appreciably change their lower cost in comparison to healthier options such as fruits and vegetables.[6]

Supermarket construction

Local and state governments can also work to pass legislation that calls for the establishment of healthy food retailers in low-income neighborhoods classified as food deserts.[7] The implementation of such policies can reduce hunger and food insecurity by increasing the availability and variety of healthy food options and providing a convenient means of access.[7] Examples of this are The Pennsylvania Fresh Food Financing Initiative and The New York City FRESH (Food Retail Expansion Health) program, which promote the construction of supermarkets in low-income neighborhoods by offering a reduction in land or building taxes for a certain period of time and providing grants, loans, and tax exemption for infrastructure costs.[91] Such policies may be limited by the oligopolistic nature of supermarkets, in which a few large supermarket chains maintain the large majority of market share and exercise considerable influence over retail locations and prices.[4]

Transportation infrastructure

If it is unfeasible to implement policies aimed at grocery store construction in low-income neighborhoods, local and state governments can instead invest in transportation infrastructure.[8] This would provide residents of low-income neighborhoods with greater access to healthy food options at more remote supermarkets.[8] This strategy may be limited by the fact that low-income populations often face time constraints in managing employment and caring for children and may not have the time to commute to buy healthy foods.[8] Furthermore, this method does not address the issue of neighborhood deprivation, failing to resolve the disparities in access to goods and services across geographical space.[4]

Community gardens

Local governments can also mitigate hunger and food insecurity in low-income neighborhoods by establishing community gardens.[9] According to the Encyclopedia of Community, a community garden is “an organized, grassroots initiative whereby a section of land is used to produce food or flowers or both in an urban environment for the personal use or collective benefit of its members."[92] Community gardens are beneficial in that they provide community members with self-reliant methods for acquiring nutritious, affordable food.[9] This contrasts with safety net programs, which may alleviate food insecurity but often foster dependency.[9]

According to the Journal of Applied Geography, community gardens are most successful when they are developed using a bottom-up approach, in which community members are actively engaged from the start of the planning process.[9] This empowers community members by allowing them to take complete ownership over the garden and make decisions about the food they grow.[9] Community gardens are also beneficial because they allow community members to develop a better understanding of the food system, the gardening process, and healthy versus unhealthy foods.[9] Community gardens thereby promote better consumption choices and allow community members to maintain healthier lifestyles.[9]

Despite the many advantages of community gardens, community members may face challenges in regard to accessing and securing land, establishing organization and ownership of the garden, maintaining sufficient resources for gardening activities, and preserving safe soils.[9]

Private sector hunger relief

The oldest type of formal hunger relief establishment used in the United States is believed to be the almshouse, but these are no longer in existence. In the 21st century, hunger relief agencies run by civil society include:

- Food pantries are the most numerous food aid establishment found within the United States. The food pantry hands out packages of grocery to the hungry. Unlike soup kitchens, they invariably give out enough food for several meals, which is to be consumed off the premises. A related establishment is the food closet, which serves a similar purpose to the food pantry, but will never be a dedicated building. Instead a food closet will be a room within a larger building like a church or community center. Food closets can be found in rural communities too small to support a food pantry. Food pantries often have procedures to prevent unscrupulous people taking advantage of them, such as requiring registration.

- Soup kitchens, along with similar establishments like food kitchens and meal centers, provide hot meals for the hungry and are the second most common type of food aid agency in the U.S. Unlike food pantry, these establishments usually provide only a single meal per visit, but they have the advantage for the end user of generally providing food with no questions asked.

- The food bank is the third most common type of food aid agency. While some will give food direct to the hungry, food banks in the U.S. generally provide a warehouse like function, distributing food to front line agencies such as food pantries and soup kitchens.

- Food rescue organizations also perform a warehouse like function, distributing food to front line organizations, though they are less common and tend to operate on a smaller scale than do food banks. Whereas food banks may receive supplies from large growers, manufacturers, supermarkets and the federal government, rescue organizations typically retrieve food from sources such as restaurants along with smaller shops and farms.

Together, these civil society food assistance establishments are sometimes called the "Emergency Food Assistance System" (EFAS). In 2010, an estimated 37 million Americans received food from the EFAS. However, the amount of aid it supplies is much less than the public sector, with an estimate made in 2000 suggesting that the EFAS is able to give out only about $9.5 worth of food per person per month. According to a comprehensive government survey completed in 2002, about 80% of emergency kitchens and food pantries, over 90% of food banks, and all known food rescue organisations, were established in the US after 1981, with much of the growth occurring after 1991.[10][11][12]

There are several federal laws in the United States that promote food donation.[93] The Bill Emerson Good Samaritan Food Donation Act encourages individuals to donate food to certain qualified nonprofit organizations and ensures liability protection to donors.[93] Similarly, Internal Revenue Code 170(e)(3) grants tax deductions to businesses in order to encourage them to donate healthy food items to nonprofit organizations that serve low-income populations.[93] Lastly, the U.S. Federal Food Donation Act of 2008 encourages Federal agencies and Federal agency contractors to donate healthy food items to non-profit organizations for redistribution to food insecure individuals.[93] Such policies curb food waste by redirecting nutritious food items to individuals in need.[93]

History

Pre-19th century

British Colonists attempting to settle in North America during the 16th and early 17th century often faced severe hunger. Compared with South America, readily available food could be hard to come by. Many settlers starved to death, leading to several colonies being abandoned. Other settlers were saved after being supplied with food by Native Americans, with the intercession of Pocahontas being a famous example. It did not take long however for colonists to adapt to conditions in the new world, discovering North America to be a place of extraordinary fertility. According to author Peter K. Eisinger, the historian Robert Beverley's portrayal of America as the "Garden of the World" was already a stock image as early as 1705.[94] By the time of the Declaration of Independence in 1776, hunger was already considerably less severe than in Western Europe. Even by 1750, low prevalence of hunger had helped provide American Colonists with an estimated life expectancy of 51 years, while in Britain the figure was 37, in France 26 - by 1800, life expectancies had improved to 56 years for the U.S., 33 years for France and dropped to 36 years for Britain.[95] The relative scarcity of hunger in the U.S. was due in part to low population pressure in relation to fertile land, and as labor shortages prevented any able-bodied person from suffering from extreme poverty associated with unemployment.[10][95]

19th century

Until the early 19th century, even the poorest citizens of the United States were generally protected from hunger by a combination of factors. The ratio of productive land to population was high. Upper class Americans often still held to the old European ideal of Noblesse oblige and made sure their workers had sufficient food. Labour shortages meant the poor could invariably find a position - although until the American Revolution this often involved indentured servitude, this at least protected the poor from the unpredictable nature of wage labor, and sometimes paupers were rewarded with their own plot of land at the end of their period of servitude. Additionally, working class traditions of looking out for each other were strong.[94][95]

Social and economic conditions changed substantially in the early 19th century, especially with the market reforms of the 1830s. While overall prosperity increased, productive land became harder to come by, and was often only available for those who could afford substantial rates. It became more difficult to make a living either from public lands or a small farm without substantial capital to buy up to date technology. Sometimes small farmers were forced off their lands by economic pressure and became homeless. American society responded by opening up numerous almshouses, and some municipal officials began giving out small sums of cash to the poor. Such measures did not fully check the rise in hunger; by 1850, life expectancy in the US had dropped to 43 years, about the same as then prevailed in Western Europe.[95]

The number of hungry and homeless people in the U.S. increased in the 1870s due to industrialization. Though economic developments were hugely beneficial overall, driving America's Gilded Age, they had a negative impact on some of the poorest citizens. As was the case in 19th century Britain, many influential Americans believed in classical liberalism and opposed government intervention to help the hungry, as they thought it could encourage dependency and would disrupt the operation of the free market. The 1870s saw the AICP and the American branch of the Charity Organization Society successfully lobby to end the practice where city official would hand out small sums of cash to the poor. Unlike in Britain though, there was no nationwide restrictions on private efforts to help the hungry, and civil society immediately began to provide alternative aid for the poor, establishing soup kitchens in U.S. cities.[94][95][96]

20th century

By the turn of the century, improved economic conditions were helping to reduce hunger for all sections of society, even the poorest.[98] The early 20th century saw a substantial rise in agricultural productivity; while this led to rural unemployment even in the otherwise "roaring" 1920s, it helped lower food prices throughout the United States. During World War I and its aftermath, the U.S. was able to send over 20 million pounds of food to relieve hunger in Europe.[99] The United States has since been a world leader for relieving hunger internationally, although her foreign aid has sometimes been criticised for being poorly targeted and politicised. An early critic who argued against the U.S. on these grounds in the 1940s was Lord Boyd-Orr, the first head of the UN's Food and Agriculture Organization.[100]

The United States' progress in reducing domestic hunger had been thrown into reverse by the Great depression of the 1930s. The existence of hunger within the U.S. became a widely discussed issue due to coverage in the Mass media. Both civil society and government responded. Existing soup kitchens and bread lines run by the private sector increased their opening times, and many new ones were established. Government sponsored relief was one of the main strands of the New Deal launched by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Some of the government established Alphabet agencies aimed to relieve poverty by raising wages, others by reducing unemployment as with the Works Progress Administration. The Federal Surplus Relief Corporation aimed to directly tackle hunger by providing poor people with food.[101] By the late 1940s, these various relief efforts combined with improved economic conditions had been successful in substantially reducing hunger within the United States.[11]

According to sociology professor Janet Poppendieck, hunger within the US was widely considered to be a solved problem until the mid-1960s.[11] By the mid-sixties, several states had ended the free distribution of federal food surpluses, instead providing an early form of food stamps, which had the benefit of allowing recipients to choose food of their liking, rather than having to accept whatever happened to be in surplus at the time. There was however a minimum charge; some people could not afford the stamps, causing them to suffer severe hunger.[11] One response from American society to the rediscovery of hunger was to step up the support provided by private sector establishments like soup kitchens and meal centers. The food bank, a new form of civil society hunger relief agency, was invented in 1967 by John van Hengel.[11] It was not however until the 1980s that U.S. food banks began to experience rapid growth.

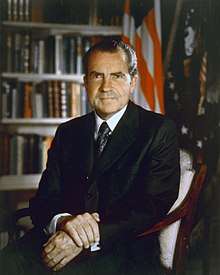

A second response to the "rediscovery" of hunger in the mid-to-late sixties, spurred by Joseph S. Clark's and Robert F. Kennedy's tour of the Mississippi Delta, was the extensive lobbying of politicians to improve welfare. The Hunger lobby, as it was widely called by journalists, was largely successful in achieving its aims, at least in the short term. In 1967 a Senate subcommittee held widely publicized hearings on the issue, and in 1969 President Richard Nixon made an emotive address to Congress where he called for government action to end hunger in the U.S.[102]

In the 1970s, U.S. federal expenditure on hunger relief grew by about 500%, with food stamps distributed free of charge to those in greatest need. According to Poppendieck, welfare was widely considered preferable to grass roots efforts, as the latter could be unreliable, did not give recipients consumer-style choice in the same way as did food stamps, and risked recipients feeling humiliated by having to turn to charity. In the early 1980s, President Ronald Reagan's administration scaled back welfare provision, leading to a rapid rise in activity from grass roots hunger relief agencies.[11][103]

Poppendieck says that for the first few years after the change, there was vigorous opposition from the political Left, who argued that the state welfare was much more suitable for meeting recipients needs. This idea was questionable to many, well other thought it was perfect for the situation. But in the decades that followed, while never achieving the reduction in hunger as did food stamps in the 1970s, food banks became an accepted part of America's response to hunger.[11][104]

The USDA Economic Research Service began releasing statistics on household food security in the U.S. in 1985.[105]

Demand for the services of emergency hunger relief agencies increased further in the late 1990s, after the "end of welfare as we know it" with President Clinton's Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act.[106]

21st century

In comparison to other advanced economies, the U.S. had high levels of hunger even during the first few years of the 21st century, due in part to greater inequality and relatively less spending on welfare. As was generally the case across the world, hunger in the U.S. was made worse by the lasting global inflation in the price of food that began in late 2006 and by the financial crisis of 2008. By 2012, about 50 million Americans were food insecure, approximately 1 in 6 of the population, with the proportion of children facing food insecurity even higher at about 1 in 4.[10]

Hunger has increasingly begun to sometimes affect even middle class Americans. According to a 2012 study by UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, even married couples who both work but have low incomes will sometimes now require emergency food assistance.[107][108][109]

In the 1980s and 90s, advocates of small government had been largely successful in un-politicizing hunger, making it hard to launch effective efforts to address the root causes, such as changing government policy to reduce poverty among low earners. In contrast to the 1960s and 70s, the 21st century has seen little significant political lobbying for an end to hunger within America, though by 2012 there had been an increase in efforts by various activists and journalists to raise awareness of the problem. American society has however responded to increased hunger by substantially increasing its provision of emergency food aid and related relief, from both the private and public sector, and from the two working together in partnership.[10]

According to a USDA report, 14.3% of American households were food insecure during at least some of 2013, falling to 14% in 2014. The report stated the fall was not statistically significant. The percentage of households experiencing very low food security remained at 5.6% for both 2013 and 2014.[110] In a July 2016 discussion on the importance of private sector engagement with the Sustainable Development Goals, Malcolm Preston the global sustainability leader at PricewaterhouseCoopers, suggested that unlike the older Millennial development goals, the SDGs are applicable to the advanced economies due to issues such as hunger in the United States. Preston stated that one in seven Americans struggle with hunger, with food banks in the US now more active than ever.[111]

See also

- A Place at the Table

- Door County, Wisconsin § Cherry crop labor sources

- Economic issues in the United States

- Feeding America

- Homelessness in the United States

- The Hunger Project

- Malnutrition in the United States

- Obesity in the United States

- United States Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs

Notes and references

- Pedersen, Traci (August 13, 2019). "Food Insecurity Common Among US College Students". Psych Central. Retrieved November 23, 2019.

- Nazmi, Aydin; Martinez, Suzanna; Byrd, Ajani; Robinson, Derrick; Bianco, Stephanie; Maguire, Jennifer; Crutchfield, Rashida M.; Condron, Kelly; Ritchie, Lorrene (September 3, 2019). "A systematic review of food insecurity among US students in higher education". Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition. 14 (5): 725–740. doi:10.1080/19320248.2018.1484316. ISSN 1932-0248.

- Lauren Bauer (May 6, 2020). "The COVID-19 crisis has already left too many children hungry in America". Brookings Institution. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- Walker, Renee; Keane, Christopher; Burke, Jessica (September 2010). "Disparities and access to healthy food in the United States: A review of food deserts literature". Health & Place. 16 (5): 876–884. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.04.013. PMID 20462784.

- Fields, Scott (October 2004). "The Fat of the Land: Do Agricultural Subsidies Foster Poor Health?". Environmental Health Perspectives. 112 (14): 820–823. doi:10.1289/ehp.112-a820. PMC 1247588. PMID 15471721.

- Popkin, Barry; Adair, Linda; Ng, Shu Wen (January 2012). "NOW AND THEN: The Global Nutrition Transition: The Pandemic of Obesity in Developing Countries". Nutrition Reviews. 70 (1): 3–21. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00456.x. PMC 3257829. PMID 22221213.

- Story, Mary; Kaphingst, Karen; Robinson-O'Brien, Ramona; Glanz, Karen (2008). "Creating Healthy Food and Eating Environments: Policy and Environmental Approaches". Annual Review of Public Health. 29: 253–272. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090926. PMID 18031223.

- Lopez, Russell P; Hynes, H Patricia (2006). "Obesity, physical activity, and the urban environment: public health research needs". Environmental Health. 5: 5–25. doi:10.1186/1476-069x-5-25. PMC 1586006. PMID 16981988.

- Corrigan, Michelle (October 2011). "Growing what you eat: Developing community gardens in Baltimore, Maryland". Applied Geography. 31 (4): 1232–1241. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2011.01.017.

- William A Dando, ed. (2012). "passim, see esp Food Assistance Landscapes in the United States by Andrew Walters and Food Aid Policies in the United States: Contrasting views by Ann Myatt James; also see Historiography of Food". Food and Famine in the 21st Century. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1598847307.

- Poppendieck, Janet (1999). "Introduction, Chpt 1". Sweet Charity?: Emergency Food and the End of Entitlement. Penguine. ISBN 978-0140245561.

- Riches, Graham (1986). "passim, see esp. Models of Food Banks". Food banks and the welfare crisis. Lorimer. ISBN 978-0888103635.

- "American Shame". New York Times. February 19, 2011. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- "Global Food Security Index". London: The Economist Intelligence Unit. March 5, 2013. Retrieved April 8, 2013.

- Coleman-Jensen, Alisha. "Household Food Security in the United States in 2018" (PDF).

- Coleman-Jensen, Alisha. "Household Food Security in the United States in 2018" (PDF).

- "What is Food Insecurity in America".

- "Definitions of Food Security". United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service.

- Coleman-Jensen, Alisha; Rabbitt, Matthew P.; Gregory, Christian A.; Singh, Anita (September 4, 2019). "Household Food Security in the United States in 2018". United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Retrieved November 23, 2019.

- Patton-López, Megan M.; López-Cevallos, Daniel F.; Cancel-Tirado, Doris I.; Vazquez, Leticia (May 1, 2014). "Prevalence and correlates of food insecurity among students attending a midsize rural university in Oregon". Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 46 (3): 209–214. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2013.10.007. ISSN 1878-2620. PMID 24406268.

- "What Is Food Insecurity in America?". Hunger and Health. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- "USDA ERS - Definitions of Food Security". ers.usda.gov. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- Jason DeParle (May 6, 2020). "As Hunger Swells, Food Stamps Become a Partisan Flash Point". The New York Times. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- Borger, C., Gearing, M., Macaluso, T., Mills, G., Montaquila, J., Weinfield, N., & Zedlewski, S. (2014). Hunger in America 2014 Executive Summary. Feeding America.

- "2014 Poverty Guidelines" (PDF). Medicaid. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- Valentine, Vikki. "Q & A: The Causes Behind Hunger in America". NPR. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- O'Brien, D., Staley, E., Torres Aldeen, H., & Uchima, S. (2004). The UPS Foundation and the Congressional Hunger Center 2004 Hunger Forum Discussion Paper: Hunger in America (The Definitions, Scope, Causes, History and Status of the Problem of Hunger in the United States). America's Second Harvest.

- Ratcliffe, Caroline (2011). "How Much Does the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Reduce Food Insecurity?". American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 93 (4): 1082–1098. doi:10.1093/ajae/aar026. PMC 4154696. PMID 25197100.

- Gundersen, C., Kreider, B., & Pepper, J. (2011). The Economics of Food Insecurity in the United States. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy. Retrieved from http://aepp.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2011/08/08/aepp.ppr022.full

- Eggebeen, D.; Lichter, D. (1991). "Race, Family Structure, and Changing Poverty Among American Children". American Sociological Review. 56 (6): 801–817. doi:10.2307/2096257. JSTOR 2096257.

- "U.S. Explanation of Vote on the Right to Food". US Mission Geneva. March 24, 2017. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- Messer, Ellen; Cohen, Marc J. (February 8, 2009). "US Approaches to Food, Nutrition Rights 1976-2008". World Hunger News. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- "The Right to Food in the United States – What can we do on the local level?". Middlebury Food Co-op. July 15, 2018. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- Lappé, Anna (September 14, 2011). "Who Says Food Is a Human Right?". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- "USA | The Right to Food around the Globe". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2020. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- The UN defines the right to food as "the right to have regular, permanent and unrestricted access, either directly or by means of financial purchases, to quantitatively and qualitatively adequate and sufficient food corresponding to the cultural traditions of the people to which the consumer belongs, and which ensure a physical and mental, individual and collective, fulfilling and dignified life free of fear." "Special Rapporteur on the right to food". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. 2020. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- Chilton, Mariana; Rose, Donald (July 2009). "A Rights-Based Approach to Food Insecurity in the United States". American Journal of Public Health. 99 (7): 1203–1211. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.130229. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 2696644. PMID 19443834.

- Cordes, Kaitlin Y. (February 25, 2014). "ABA Resolution on the Right to Food". Righting Food. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- Gundersen, Craig (October 1, 2019). "The Right to Food in the United States: The Role of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)". American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 101 (5): 1328–1336. doi:10.1093/ajae/aaz040. ISSN 0002-9092.

- Narula, Smita; Jackson, Jesse (October 30, 2013). "A Dream Deferred: The Right to Food in America". HuffPost. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- "Household Food Security in the United States in 2011" (PDF). USDA. September 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 28, 2013. Retrieved April 8, 2013.

- "Childhood Hunger In America" (PDF). No Kid Hungry. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- "USDA ERS - Key Statistics & Graphics". ers.usda.gov. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- "Facts About Child Hunger in America | Feeding America". feedingamerica.org. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- Kirkpatrick, Sharon; McIntyre, Lynn; Potestio, Melissa (August 2010). "Child Hunger and Long-term Adverse Consequences for Health". JAMA Pediatrics. 164 (8): 754–62. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.117. PMID 20679167.

- Alaimo, K.; Frongillo Jr., E.A.; Olson, C.M. (2001). "Food insufficiency and American school-aged children's cognitive, academic, and psychosocial development". Pediatrics. 108 (1): 44–53. PMID 11433053.

- Lavorato, Dina; McIntyre, Lynn; Patten, Scott; Williams, Jeanne (August 5, 2013). "Depression and suicide ideation in late adolescence and early adulthood are an outcome of child hunger". Journal of Affective Disorders. 150 (1): 123–129. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.029. PMID 23276702.

- Patton-López, Megan M.; López-Cevallos, Daniel F.; Cancel-Tirado, Doris I.; Vazquez, Leticia (May 2014). "Prevalence and Correlates of Food Insecurity Among Students Attending a Midsize Rural University in Oregon". Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 46 (3): 209–214. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2013.10.007. PMID 24406268.

- Pia Chaparro, M; Zaghloul, Sahar S; Holck, Peter; Dobbs, Joannie (November 2009). "Food insecurity prevalence among college students at the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa". Public Health Nutrition. 12 (11): 2097–2103. doi:10.1017/S1368980009990735. ISSN 1368-9800. PMID 19650961.

- Davidson, A. R.; Morrell, J. S. (January 2, 2020). "Food insecurity prevalence among university students in New Hampshire". Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition. 15 (1): 118–127. doi:10.1080/19320248.2018.1512928. ISSN 1932-0248.

- Gaines, Alisha; Robb, Clifford A.; Knol, Linda L.; Sickler, Stephanie (July 2014). "Examining the role of financial factors, resources and skills in predicting food security status among college students: Food security and resource adequacy". International Journal of Consumer Studies. 38 (4): 374–384. doi:10.1111/ijcs.12110.

- Bruening, Meg; Brennhofer, Stephanie; van Woerden, Irene; Todd, Michael; Laska, Melissa (September 2016). "Factors Related to the High Rates of Food Insecurity among Diverse, Urban College Freshmen". Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 116 (9): 1450–1457. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2016.04.004. PMC 5520984. PMID 27212147.

- Morris, Loran Mary; Smith, Sylvia; Davis, Jeremy; Null, Dawn Bloyd (June 2016). "The Prevalence of Food Security and Insecurity Among Illinois University Students". Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 48 (6): 376–382.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2016.03.013.

- Moon, Emily (June 28, 2019). "Half of College Students Are Food Insecure. Are Universities Doing Enough to Help Them?". Pacific Standard. Retrieved November 23, 2019.

- Cady, Clare L. (January 1, 2014). "Food Insecurity as a Student Issue". Journal of College and Character. 15 (4). doi:10.1515/jcc-2014-0031. ISSN 1940-1639.

- Gundersen, Craig; Ziliak, James (September 1, 2013). "The State of Senior Hunger in America 2011: An Annual Report" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - DeGood, Kevin. "Aging in Place, Stuck without Options: Fixing the Mobility Crisis Threatening the Baby Boom Generation". Transportation for America.

- "Improve Access to Nutritious Food in Rural Areas". sog.unc.edu.

- "Facts about Senior Hunger in America | Feeding America". feedingamerica.org. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- Meals On Wheels Research Foundation (2012). "Senior Hunger Report Card". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Jaspreet, Bindra; Borden, Enid (2011). "Spotlight On Senior Health: Adverse Health Outcomes of Food Insecure Older Americans (Executive Summary)" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Heflin, Colleen; Huang, Jin; Nam, Yunju; Sherraden, Michael. "Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Food Insufficiency: Evidence from a Statewide Probability Sample of White, African American, American Indian, and Hispanic Infants". Center for Social Development, Washington University in St. Louis. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Feeding America (2010). "When the Pantry is Bare: Emergency Food Assistance and Hispanic Children (Executive Summary)". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "African American Hunger and Poverty Facts | Feeding America". feedingamerica.org. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- "Hispanic and Latino Hunger in America | Feeding America". feedingamerica.org. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- "Rural Hunger Fact Sheet". Feeding America. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- "USDA ERS - Key Statistics & Graphics". ers.usda.gov. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- Bower, Kelly; Gaskin, Darrell; Rohde, Charles; Thorpe, Roland (January 2014). "The intersection of neighborhood racial segregation, poverty, and urbanicity and its impact on food store availability in the United States". Preventive Medicine. 58: 33–39. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.10.010. PMC 3970577. PMID 24161713.

- Burke, Jessica; Keane, Christopher; Walker, Renee (September 2010). "Disparities and access to healthy food in the United States: A review of food deserts literature". Health & Place. 16 (5): 876–884. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.04.013. PMID 20462784.

- "Farm Income and Wealth Statistics". United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on May 1, 2017. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- "California's Agricultural Employment" (PDF). Labor Market Information. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 29, 2016. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- "Food Workers-Food Justice: Linking food, labor and Immigrant rights" (PDF). Food First Backgrounder.

- "Food Workers-Food Justice: Linking food, labor and Immigrant rights" (PDF). Food First Backgrounder.

- Algert, Susan J.; Reibel, Michael; Renvall, Marian J. (2006). "Barriers to Participation in the Food Stamp Program Among Food Pantry Clients in Los Angeles". American Journal of Public Health. 96 (5): 807–809. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.066977. PMC 1470578. PMID 16571694.

- Kulish, Nicholas; Yee, Vivian; Dickerson, Caitlin; Robbins, Liz; Santos, Fernanda; Medina, Jennifer (February 21, 2017). "Trump's Immigration Policies Explained". The New York Times.

- Schlosberg, David (2013). "Theorising environmental justice: the expanding sphere of a discourse". Environmental Politics. 22: 37–55. doi:10.1080/09644016.2013.755387.

- "The High Stake in Immigration Reform for Our Communities-Central Valley" (PDF). Center for the Study of Immigrant Integration.

- "Most Polluted Cities". State Of The Air.

- "Physical And Psychological Effects Of Starvation In Eating Disorders | SEDIG". sedig.org. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- "Facts About Child Hunger in America | Feeding America". feedingamerica.org. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- "Women, Infants & Children Nutrition | Feeding America". feedingamerica.org. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- Gundersen, Craig. "The Health Consequences of Senior Hunger in the United States: Evidence from 1999-2014 NHANES" (PDF).

- Universal in the sense that anyone who meets the criteria is given aid, unlike most other programs which are targeted at specific types of citizen like children, women or the disabled.

- SNAP Monthly Data

- Becker, Elizabeth (November 14, 2001). "Shift From Food Stamps to Private Aid Widens". New York Times. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- JASON DePARLE; ROBERT GEBELOFF (November 28, 2009). "Food Stamp Use Soars, and Stigma Fade". New York Times. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- McVeigh, Karen (December 24, 2013). "Demand for food stamps soars as cuts sink in and shelves empty". The Guardian. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- KIM SEVERSON; WINNIE HU (November 8, 2013). "Cut in Food Stamps Forces Hard Choices on Poor". The New York Times. Retrieved November 17, 2013.

- NICHOLAS D. KRISTOF (November 16, 2013). "Prudence or Cruelty?". The New York Times. Retrieved November 17, 2013.

- Holzman, David C. (April 2010). "DIET AND NUTRITION: White House Proposes Healthy Food Financing Initiative". Environmental Health Perspectives. 118 (4): A156. doi:10.1289/ehp.118-a156. PMC 2854743. PMID 20359982.

- Cummins, Steve; Flint, Ellen; Matthews, Stephen A. (February 2014). "New Neighborhood Grocery Store Increased Awareness Of Food Access But Did Not Alter Dietary Habits Or Obesity". Health Affairs. 33 (2): 283–291. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0512. PMC 4201352. PMID 24493772.

- Glover, T.D. (2003). "Community garden movement". Encyclopedia of Community: 264–266.

- "Recovery/Donations". United States Department of Agriculture Office of the Chief Economist.

- Peter K. Eisinger (1998). "chpt. 1". Toward an End to Hunger in America. Brookings Institution. ISBN 978-0815722816.

- Robert Fogel (2004). "chpt. 1". The Escape from Hunger and Premature Death, 1700–2100: Europe, America, and the Third World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521004886.

- Todd DePastino (2005). Citizen Hobo: How a Century of Homelessness Shaped America. Chicago University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0226143798.

- Richard Nixon (May 3, 1969). "Special Message to the Congress Recommending a Program To End Hunger in America". UCSB. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- Although in 1900, U.S. life expectancy was still only estimated at 48 years, 2 years lower than in 1725 – see Fogel (2004) chpt 1.

- Hoover, Herbert (1941). History of the United States Food Administration 1917-1919. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. p. 42.

- Vernon, James (2007). "Chpt. 5". Hunger: A Modern History. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674026780.

- The FSRC also helped farmers by buying food they were unable to sell profitably on the market.

- R Shep Melnick (1994). "Chpt. 9: The Surprising success of food stamps". Between the Lines: Interpreting Welfare Rights. Brookings Institution. ISBN 978-0815756637.

- Walter, Andrew (2012). William A Dando (ed.). Food and Famine in the 21st Century. ABC-CLIO. pp. 171–181. ISBN 978-1598847307.

- "HOUSEHOLD FOOD SECURITY IN THE GLOBAL NORTH: CHALLENGES AND RESPONSIBILITIES REPORT OF WARWICK CONFERENCE" (PDF). Warwick University. July 6, 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 12, 2013. Retrieved August 28, 2012.

- "Food Security in the U.S. - Overview". USDA Economic Research Service. September 4, 2019. Retrieved November 23, 2019.

- Watson, Debra (May 11, 2002). "Recession and welfare reform increase hunger in US". World Socialist Web Site. Retrieved September 6, 2012.

- Ferreras, Alex (July 11, 2012). "Thousands More in Solano, Napa Counties are Turning to Food Banks". Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- Turner, John (September 20, 2012). "Poverty and hunger in America". The Guardian. Retrieved October 1, 2012.

- Gleaners Indiana Food bank Retrieved 2012-07-18

- Alisha Coleman-Jensen; Matthew Rabbitt; Christian Gregory; Anita Singh (September 2015). "Household Food Security in the United States in 2014". United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on July 29, 2016. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- Slavin, Terry (July 25, 2016). "SDGs: We need more than just sunshine stories". ethicalcorp.com. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Hunger in the United States |

- Facts on Hunger in the USA, 2013, from the World Hunger Education Service

- Food Insecurity, a special issue from the Journal of Applied Research on Children (2012)