Homer Plessy

Homer Adolph Plessy, originally Homère Adolphe Plessy (March 17, 1862 – March 1, 1925), was a French-speaking Creole from Louisiana, best known for being the plaintiff in the United States Supreme Court decision Plessy v. Ferguson.

Homer Adolph Plessy | |

|---|---|

| Born | Homère Patris Plessy[1] March 17, 1862 New Orleans, Orleans Parish, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Died | March 1, 1925 (aged 62) Metairie, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Resting place | Saint Louis Cemetery No. 1 in New Orleans |

| Occupation | Shoemaker Insurance collector Civil rights activist |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Louise Bordenave Plessy (married 1888–1925, his death) |

| Children | 3 |

| Parent(s) | Adolph Plessy and Rosa Debergue Plessy; Stepfather: Victor M. Dupart |

Arrested, tried and convicted in New Orleans of a violation of one of Louisiana's racial segregation laws, he appealed through Louisiana state courts to the U.S. Supreme Court and lost. The resulting "separate but equal" decision against him had wide consequences for civil rights in the United States. The decision legalized state-mandated segregation anywhere in the United States so long as the facilities provided for both blacks and whites were putatively "equal".

Homer Plessy was a free person of color born to a family that came to America free from Haiti and France. His parents were French-speaking Creoles, Haitian refugees who fled the revolution.

At that time, federal troops under General Benjamin Franklin Butler were occupying Louisiana as a result of the American Civil War, having liberated African Americans in New Orleans who had been in bondage. As a result, Blacks could marry whomever they chose, sit in any streetcar seat and, briefly, attend integrated schools.[2]

As an adult, Plessy experienced the reversal of the gains achieved under the federal occupation, following the withdrawal of federal troops in 1877 on the orders of U.S. President Rutherford B. Hayes.[3]

Due to Plessy’s phenotype being white, Plessy could have ridden in a railroad car restricted to people classified as White. However, under the racial policies of the time, he was an "octoroon" having 1/8th African-American heritage, and therefore was considered Black. Hoping to strike down segregation laws, the Citizens’ Committee of New Orleans (Comité des Citoyens) recruited Plessy to deliberately violate Louisiana's 1890 separate-car law. To pose a clear test, the Citizens’ Committee gave notice of Plessy’s intent to the railroad, which opposed the law because it required adding more cars to its trains.[3]

On June 7, 1892, Plessy bought a first-class ticket on a train from New Orleans and sat in the car for white riders only. The Committee had hired a private detective with arrest powers to take Plessy off the train at Press and Royal streets, to ensure that he was charged with violating the state’s separate-car law and not some other misdemeanor.[3]

Everything that the committee had organized occurred as planned, except for the decision of the Supreme Court in 1896.

By then the composition of the U.S. Supreme Court had gained a more segregationist tilt, and the committee knew it would likely lose. But it chose to press the cause anyway, [author Keith] Medley said. “It was a matter of honor for them, that they fight this to the very end.”[3]

Biography

Homer Plessy was born on March 17, 1862, in New Orleans to Joseph Adolphe Plessy and Rosa Debergue, members of New Orleans' French-speaking Creole society.[4] Another in this Creole society was Plessy's compatriot Walter L. Cohen, who obtained an appointment as customs inspector from U.S. President William McKinley.[5]

Homer Plessy's paternal grandfather was Germain Plessy, a white Frenchman born in Bordeaux c. 1777.[6] Germain Plessy arrived in New Orleans with thousands of other French expatriates who fled Saint-Domingue in the wake of the slave rebellion led by Toussaint L'Ouverture that wrested Haiti from Napoleon in the 1790s.[6] Germain Plessy married Catherine Mathieu, a free woman of color, and they had eight children, including Homer Plessy's father, Joseph Adolphe Plessy.[6]

Homer Plessy's middle name would later appear as Adolphe after his father, a carpenter, on his birth certificate. Plessy belonged to Louisiana's French-speaking Creole class, which American society did not understand or accept. Plessy grew up speaking French. Adolphe Plessy died when Homer was seven years old. In 1871, his mother Rosa Debergue Plessy, a seamstress, married Victor M. Dupart, a clerk for the U.S. Post Office who supplemented his income by working as a shoemaker. Plessy too became a shoemaker. During the 1880s, he worked at Patricio Brito's shoe-making business on Dumaine Street near North Rampart. New Orleans city directories from 1886 to 1924 list his occupations as shoemaker, laborer, clerk, and insurance agent.[7]

By 1887, Plessy had become vice-president of the Justice, Protective, Educational, and Social Club, a group dedicated to reforming public education in New Orleans. In 1888, Plessy, then twenty-five years old, was married to nineteen-year-old Louise Bordenave by Father Joseph Subileau at St. Augustine Church which is located at 1210 Gov. Nicholls Street in New Orleans.[8] Plessy's employer Brito served as a witness. In 1889, the Plessys moved to Faubourg Tremé at 1108 North Claiborne Avenue. He registered to vote in the Sixth Ward's Third Precinct.

At age thirty, shoemaker Homer Plessy was younger than most members of the Comité des Citoyens. He did not have their stellar political histories, literary prowess, business acumen, or law degrees. Indeed, his one attribute was being white enough to gain access to the train and black enough to be arrested for doing so. This shoemaker sought to make an impact on society that was larger than simply making its shoes. When Plessy was a young boy, his stepfather was a signatory to the 1873 Unification Movement—an effort to establish principles of equality in Louisiana. As a young man, Plessy displayed a social awareness and served as vice president of an 1880s educational-reform group. And in 1892, he volunteered for a mission rife with unpredictable consequences and backlashes. Comité des Citoyens lawyers Albion Tourgee, James C. Walker and Louis Martinet vexed over legal strategy. Treasurer Paul Bonseigneur handled finances. As a contributor to The Crusader newspaper, Rodolphe Desdunes inspired with his writings. Plessy's role consisted of four tasks: get the ticket, get on the train, get arrested, and get booked.[9]

Plessy v. Ferguson

The Comité des Citoyens ("Citizens' Committee") was a civil rights group made up of African Americans, whites, and Creoles. The committee vigorously opposed the recently Separate Car Act.

In 1892, the Citizens' Committee asked Plessy to agree to violate Louisiana's Separate Car law that required the segregation of passenger trains by race. On June 7, 1892, Plessy, then thirty years old and resembling a white male in skin color and other physical characteristics, bought a first-class ticket on the East Louisiana Railroad running between New Orleans and Covington, the seat of now suburban St. Tammany Parish. He sat in the "whites-only" passenger car. When the conductor came to collect his ticket, Plessy told him that he was 7/8 white and that he refused to sit in the "blacks-only" car. Plessy was immediately arrested by Detective Chris C. Cain, put into the Orleans Parish jail and released the next day on a $500 bond.

Plessy's case was heard before Judge John Howard Ferguson one month after his arrest. Tourgée argued that Plessy's civil rights, as granted by the Thirteenth and Fourteenth amendments of the U.S. Constitution, had been violated. Ferguson denied this argument and ruled that Louisiana, under state law, had the power to set rules that regulated railroad business within its borders.

The Louisiana State Supreme Court affirmed Ferguson's ruling and refused to grant a rehearing. However it did allow a petition for writ of error. This petition was accepted by the United States Supreme Court and four years later, in April 1896, arguments for Plessy v. Ferguson began. Tourgée argued that the state of Louisiana had violated the Thirteenth Amendment that granted freedom to the slaves, and the Fourteenth Amendment that stated, "no state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States;nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, and property without due process of law."

On May 18, 1896, Justice Henry Billings Brown delivered the majority opinion in favor of the State of Louisiana. In part, the opinion read, "The object of the Fourteenth Amendment was undoubtedly to enforce the absolute equality of the two races before the law, but in the nature of things it could not have been intended to abolish distinctions based on color, or to enforce social, as distinguished from political equality, or a commingling of the two races upon terms unsatisfactory to the either ..."

The lone dissenting vote was cast by Justice John Marshall Harlan, a Kentucky Republican who repeatedly asserted that the U.S. constitution was "color blind."[10]

The "Separate but Equal" doctrine, enshrined by the Plessy ruling, remained valid until 1954 when it was overturned by the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education, and later completely outlawed by the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964. Though the Plessy case did not involve education, it formed the legal basis of separate school systems for the following fifty-eight years.

Plessy's life after the Supreme Court case

After the Supreme Court ruling, Plessy went back into relative anonymity. He fathered children, continued to participate in the religious and social life of his community, and later sold and collected insurance premiums for the People's Life Insurance Company. He died in 1925 at the age of 62. His obituary read: "Homer Plessy — on Sunday, March 1, 1925, at 5:10 a.m. beloved husband of Louise Bordenave." He was buried in the Debergue-Blanco family tomb in St. Louis Cemetery #1.

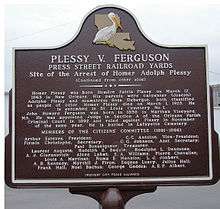

Homer Plessy historical marker

On February 12, 2009, the Plessy & Ferguson Foundation of New Orleans honored the successes of the civil rights movement by taking part in the placing of a historical marker at the corner of Press and Royal streets, the site of Homer Plessy's arrest in New Orleans in 1892.[11]

On February 10, 2009, Keith Plessy and Phoebe Ferguson, descendants of the players on both sides of the Supreme Court case, appeared together on television station WLTV in New Orleans.[12] They announced the formation of the Plessy & Ferguson Foundation for Education, Preservation and Outreach. The foundation will work to create new ways to teach the history of civil rights through film, art, and public programs designed to create understanding of this historic case and its effect on the American conscience. Keith Plessy and Phoebe Ferguson appeared together at the site of the railroad tracks in New Orleans where Homer Plessy had been denied seating.[13]

Photo confusion

Photos of P. B. S. Pinchback are often mistakenly described as photos of Homer Plessy. No photos of Homer Plessy are known to exist. [14]

References

- Rifkin, Glenn (January 31, 2020). "Overlooked No More: Homer Plessy, Who Sat on a Train and Stood Up for Civil Rights". "The New York Times". "The New York Times". Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- Medley, Keith Weldon (2003). We As Freemen: Plessy v. Ferguson. Gretna, LA: Pelican. p. 252. ISBN 1-58980-120-2.

- Reckdahl, Katy (2009-02-11). "Plessy and Ferguson unveil plaque today marking their ancestors' actions". The Times-Pickayune. Retrieved 2014-03-07. Descendants of Plessy and Ferguson in newspaper article and photograph.

- Medley, Keith Weldon (2003). We As Freemen: Plessy v. Ferguson. Gretna, LA: Pelican. p. 252. ISBN 1-58980-120-2. p. 20

- "Louisiana Historical Association, A Dictionary of Louisiana Biography (lahistory.org)". lahistory.org. Archived from the original on February 25, 2012. Retrieved December 21, 2010.

- Medley, Keith Weldon (2003). We As Freemen: Plessy v. Ferguson. Gretna, LA: Pelican. p. 252. ISBN 1-58980-120-2. p. 21

- "Homer Adolph Plessy", A Dictionary of Louisiana Biography, Vol. 2 (1988), p. 655

- "St. Augustine Catholic Church of New Orleans: Homer Plessy". staugustinecatholicchurch-neworleans.org. Archived from the original on 2013-05-15.

- Medley, Keith Weldon (2003). We As Freemen: Plessy v. Ferguson. Gretna, LA: Pelican. p. 252. ISBN 1-58980-120-2. p. 17

- Rifkin, Glenn (2020-01-31). "Overlooked No More: Homer Plessy, Who Sat on a Train and Stood Up for Civil Rights". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- Archived February 21, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Archived February 21, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Ted Jackson / The Times-Picayune. "Plessy and Ferguson unveil plaque today marking their ancestors' actions". NOLA.com. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- Mike, Scott (2017-02-02). "No, Internet, this is not Homer Plessy. But who is it?". nola.com. Nola Media Group. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Homer Plessy. |

- Elliott, Mark (2006). Color-Blind Justice: Albion Tourgée and the Quest for Racial Equality from the Civil War to Plessy v. Ferguson. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-518139-5.

- Tushnet, Mark (2008). I dissent: Great Opposing Opinions in Landmark Supreme Court Cases. Boston: Beacon Press. pp. 69–80. ISBN 978-0-8070-0036-6.

- Brook, Thomas (1997). Plessy v. Ferguson: A Brief History with Documents. Boston: Bedford Books.

- Fireside, Harvey (2004). Separate and Unequal: Homer Plessy and the Supreme Court Decision That Legalized Racism. New York: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 0-7867-1293-7.

- Lofgren, Charles A. (1987). The Plessy Case: A Legal-Historical Interpretation. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Medley, Keith Weldon (2003). We As Freemen: Plessy v. Ferguson. Gretna, LA: Pelican. p. 252. ISBN 1-58980-120-2. Review

- Chin, Gabriel J. (1996). "The Plessy Myth: Justice Harlan and the Chinese Cases". Iowa Law Review. 82: 151. SSRN 1121505.