Hanfu movement

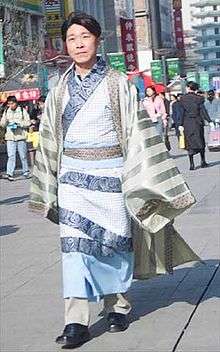

The hanfu movement (simplified Chinese: 汉服运动; traditional Chinese: 漢服運動) is a social movement seeking to revitalize ancient Han Chinese fashion that developed in China at the beginning of the 21st century.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

Background

A common misconception among Han Chinese was that Manchu clothing was entirely separate from Hanfu. In fact, Manchu clothes were simply modified Ming Hanfu but the Manchus promoted the misconception that their clothing was of different origin. Manchus originally did not have their own cloth or textiles and the Manchus had to obtain Ming dragon robes and cloth when they paid tribute to the Ming dynasty or traded with the Ming. These Ming robes were modified, cut and tailored to be narrow at the sleeves and waist with slits in the skirt to make it suitable for falconry, horse riding and archery. [8] The Ming robes were simply modified and changed by Manchus by cutting it at the sleeves and waist to make them narrow around the arms and waist instead of wide and added a new narrow cuff to the sleeves.[9] The new cuff was made out of fur. The robe's jacket waist had a new strip of scrap cloth put on the waist while the waist was made snug by pleating the top of the skirt on the robe.[10] The Manchus added sable fur skirts, cuffs and collars to Ming dragon robes and trimming sable fur all over them before wearing them.[11] Han Chinese court costume was modified by Manchus by adding a ceremonial big collar (da-ling) or shawl collar (pijian-ling).[12] It was mistakenly thought that the hunting ancestors of the Manchus skin clothes became Qing dynasty clothing, due to the contrast between Ming dynasty clothes unshaped cloth's straight length contrasting to the odd-shaped pieces of Qing dynasty long pao and chao fu. Scholars from the west wrongly thought they were purely Manchu. Chao fu robes from Ming dynasty tombs like the Wanli emperor's tomb were excavated and it was found that Qing chao fu was similar and derived from it. They had embroidered or woven dragons on them but are different from long pao dragon robes which are a separate clothing. Flaired skirt with right side fastenings and fitted bodices dragon robes have been found[13] in Beijing, Shanxi, Jiangxi, Jiangsu and Shandong tombs of Ming officials and Ming imperial family members. Integral upper sleeves of Ming chao fu had two pieces of cloth attached on Qing chao fu just like earlier Ming chao fu that had sleeve extensions with another piece of cloth attached to the bodice's integral upper sleeve. Another type of separate Qing clothing, the long pao resembles Yuan dynasty clothing like robes found in the Shandong tomb of Li Youan during the Yuan dynasty. The Qing dynasty chao fu appear in official formal portraits while Ming dynasty Chao fu that they derive from do not, perhaps indicating the Ming officials and imperial family wore chao fu under their formal robes since they appear in Ming tombs but not portraits. Qing long pao were similar unofficial clothing during the Qing dynasty.[14] The Yuan robes had hems flared and around the arms and torso they were tight. Qing unofficial clothes, long pao, derived from Yuan dynasty clothing while Qing official clothing, chao fu, derived from unofficial Ming dynasty clothing, dragon robes. The Ming consciously modeled their clothing after that of earlier Han Chinese dynasties like the Song dynasty, Tang dynasty and Han dynasty. In Japan's Nara city, the Todaiji temple's Shosoin repository has 30 short coats (hanpi) from Tang dynasty China. Ming dragon robes derive from these Tang dynasty hanpi in construction. The hanpi skirt and bodice are made of different cloth with different patterns on them and this is where the Qing chao fu originated.[15] Cross-over closures are present in both the hanpi and Ming garments. The eighth century Shosoin hanpi's variety show it was in vogue at the tine and most likely derived from much more ancient clothing. Han dynasty and Jin dynasty (266–420) era tombs in Yingban, to the Tianshan mountains south in Xinjiang have clothes resembling the Qing long pao and Tang dynasty hanpi. The evidence fron excavated tombs indicates that China had a long tradition of garments that led to the Qing chao fu and it was not invented or introduced by Manchus in the Qing dynasty or Mongols in the Yuan dynasty. The Ming robes that the Qing chao fu derived from were just not used in portraits and official paintings but were deemed as high status to be buried in tombs. In some cases the Qing went further than the Ming dynasty in imitating ancient China to display legitimacy with resurrecting ancient Chinese rituals to claim the Mandate of Heaven after studying Chinese classics. Qing sacrificial ritual vessels deliberately resemble ancient Chinese ones even more than Ming vessels.[16] Tungusic people on the Amur river like Udeghe, Ulchi and Nanai adopted Chinese influences in their religion and clothing with Chinese dragons on ceremonial robes, scroll and spiral bird and monster mask designs, Chinese New Year, using silk and cotton, iron cooking pots, and heated house from China during the Ming dynasty.[17]

The Spencer Museum of Art has six long pao robes that belonged to Han Chinese nobility of the Qing dynasty (Chinese nobility).[18] Ranked officials and Han Chinese nobles had two slits in the skirts while Manchu nobles and the Imperial family had 4 slits in skirts. All first, second and third rank officials as well as Han Chinese and Manchu nobles were entitled to wear 9 dragons by the Qing Illustrated Precedents. Qing sumptuary laws only allowed four clawed dragons for officials, Han Chinese nobles and Manchu nobles while the Qing Imperial family, emperor and princes up to the second degree and their female family members were entitled to wear five clawed dragons. However officials violated these laws all the time and wore 5 clawed dragons and the Spencer Museum's 6 long pao worn by Han Chinese nobles have 5 clawed dragons on them.[19]

When the Manchus established the Qing dynasty, the authorities issued decrees having Han Chinese men to adopt Manchu hairstyle by shaving their hair on the front of the head and braiding the hair on the back of the head into pigtails. The resistances against the hair shaving policy were suppressed.[21] Han Chinese did not object to wearing the queue braid on the back of the head as they traditionally wore all their hair long, but fiercely objected to shaving the forehead so the Qing government exclusively focused on forcing people to shave the forehead rather than wear the braid. Han rebels in the first half of the Qing who objected to Qing hairstyle wore the braid but defied orders to shave the front of the head. One person was executed for refusing to shave the front but he had willingly braided the back of his hair. It was only later westernized revolutionaries, influenced by western hairstyle who began to view the braid as backward and advocated adopting short haired western hairstyles.[22] Han rebels against the Qing like the Taiping even retained their queue braids on the back but the symbol of their rebellion against the Qing was the growing of hair on the front of the head, causing the Qing government to view shaving the front of the head as the primary sign of loyalty to the Qing rather than wearing the braid on the back which did not violate Han customs and which traditional Han did not object to.[23] Koxinga insulted and criticized the Qing hairstyle by referring to the shaven pate looking like a fly.[24] Koxinga and his men objected to shaving when the Qing demanded they shave in exchange for recognizing Koxinga as a feudatory.[25] The Qing demanded that Zheng Jing and his men on Taiwan shave in order to receive recognition as a fiefdom. His men and Ming prince Zhu Shugui fiercely objected to shaving.[26]

Some Han civilian men also voluntarily adopted Manchu clothing like changshan on their own free will. By the late Qing, not only officials and scholars, but a great many commoners as well, started to wear Manchu attire.[27][28]

Proponents of the movement claim that hanfu's chief characteristics were symbolic of cultural moral and ethical values: "the left collar covering the right represents the perfection of human culture on human nature and the overcoming of bodily forces by the spiritual power of ethical ritual teaching; the expansive cutting and board sleeve represents a moral, concordant relation between nature and human creative power; the use of the girdle to fasten the garment over the body represents the constraints of Han culture to limit human's desire that would incur amoral deed. In the Qing Dynasty, officials replaced the hanfu with the attire of Manchu. Though many people believe that the qipao is China's national costume, it is fairly modern.[29]

In the Edo period of Tokugawa Shogunate Japan orders were passed for Japanese men to shave the pate on the front of their head (the chonmage hairstyle) and shave their beards, facial hair and side whiskers.[30] This was similar to the Qing dynasty queue order imposed by Dorgon making men shave the pates on the front of their heads.[31]

Traditional Ming dynasty Hanfu robes given by the Ming Emperors to the Chinese noble Dukes Yansheng descended from Confucius are still preserved in the Confucius Mansion after over five centuries. Robes from the Qing emperors are also preserved there.[32][33][34][35][36] The Jurchens in the Jin dynasty and Mongols in the Yuan dynasty continued to patronize and support the Confucian Duke Yansheng.[37]

History

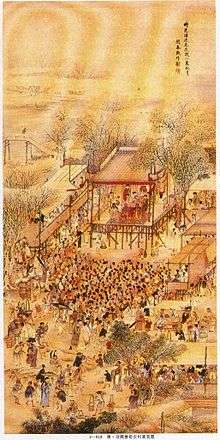

According to Asia Times Online, the hanfu movement may have begun around 2003. Wang Letian from Zhengzhou, China, publicly wore hanfu. He and his followers inspired others to reflect on the cultural identity of Han Chinese. They organized the hanfu movement as an initiative in a broader effort to stimulate a Han Chinese cultural renaissance.[38] In the same year of 2003, supporters of Han revivalism launched the website Hanwang (Chinese: 漢網, "Han Network") to promote traditional Han clothing, however some sources claim this to be alongside a Han supremacist agenda.[5]

In February 2007, advocates of hanfu submitted a proposal to the Chinese Olympic Committee to have it be the official clothing of the Chinese team in the 2008 Summer Olympics.[39] The Chinese Olympic Committee rejected the proposal in April 2007.[40]

Definition of hanfu

According to Dictionary of Old Chinese Clothing (Chinese: 中國衣冠服飾大辭典), the term hanfu means "dress of the Han people."[41] This term, which is not commonly used in ancient times, can be found in some historical records from Han, Tang, Song, and Ming dynasties and the Republican era in China.[42][43][44][45][46]

Critics have contended that the term hanfu is a modern development. An article published by Chinese Newsweek in September 2005 reported that it is not included in the authoritative dictionary of Standard Mandarin Chinese "Contemporary Chinese Dictionary" (Chinese: 現代漢語詞典) and that it was coined by Internet users around the year 2003.[47]

Professor of China Youth University of Political Studies Zhang Xian (Chinese: 張跣) asserts that hanfu is a modern concept publicized by student advocates of the hanfu movement who created a standard of pre-Qing Han Chinese fashion without accurate academic research and propagated it on collaborative, web-based encyclopedias such as Baidu Baike and Hanwang.[48] In the same vein, the American scholar of contemporary Chinese society, professor of Macquarie University Kevin Carrico criticized the hanfu for being an "invented style of dress" which "made the transition from a fantastic invented tradition to a distant image on a screen to a physical reality in the streets of China, in which one could wrap and recognise oneself".[49] He maintains that there is no clear history indicating that there was any specific apparel in existence under the name hanfu.[49]

Chinese researcher Hua Mei (Chinese: 華梅), interviewed by student advocates of the hanfu movement in 2007, recognizes that defining hanfu is no simple matter, as there was no uniform style of Chinese fashion throughout the millennia of its history. Because of its constant evolution, she questions which period's style can rightly be regarded as traditional. Nonetheless, she explains that hanfu has historically been used to broadly refer to indigenous Chinese clothing in general. Observing that the apparel most often promoted by the movement are based on the Han-era quju and zhiju, she suggests that other styles, especially that of the Tang era, would also be candidates for revival in light of this umbrella definition.[50]

Professor of Aichi University, cultural anthropologist Zhou Xing (Chinese: 周星) maintains that the term hanfu was not commonly used in ancient times and refers to the traditional costume as imagined by participants of the hanfu movement. Like Hua, he notes that the term hanfu classically referred to clothing that Han people wore in general, but in contrast, he argues that, on this basis, it is not the same as the hanfu as defined by participants of the movement.[51][52]

Controversy

Among the opposition to the hanfu movement, a common concern is its implication for ethnic minorities. Skeptics fear that there is an element of exclusivity which could brew ethnic tensions, especially if it were to be nationalized.[53][54] For this reason, supporters of the movement are sometimes labeled as "Han chauvinists".[53]

Nevertheless, it has been insisted by some hanfu advocates that none of them have ever suggested that minorities must abandon their own indigenous styles of dress and that personal preference for a style of fashion can be independent of political or nationalistic motives.[53] Students consulted by Hua Mei cited the persistence of indigenous clothing among Chinese minorities, and the usage of kimono in Japan, hanbok in North Korea and South Korea, and traditional clothing used in India as an inspiration for the hanfu movement.[50] Even some ardent enthusiasts interviewed by the South China Morning Post in 2017, among them the Hanfu Society at Guangzhou University have cautioned against extending the dress beyond social normalization among Han Chinese people, acknowledging the negative repercussions politicization of the movement may have on society.[54]

According to Kevin Carrico, an lecturer at Monash University, there is a belief that the movement is inherently racial at its core, insists in that it is built on the narrative that the Manchu rulers of the Qing dynasty were single-mindedly dedicated to the destruction of the Han people and thus of China itself, fundamentally transforming Chinese society and shifting its essence "from civilisation to barbarism". He argues that real atrocities such as the Yangzhou massacre, during which Manchu soldiers devastated the city of Yangzhou, and the forceful imposition of the queue decree, are fused with the imaginary injustice of the forcible erasure of Han clothing. According to his research, underpinning the movement are conspiracy theories made by some hanfu advocates which claim that a secret Manchu plot for restoration has been underway since the start of the post-1978 reform era, such that the Manchus secretly control every important party-state institution, including the People’s Liberation Army, the Party Propaganda Department, the Ministry of Culture and especially the National Population and Family Planning Commission.[55]

According to James Leibold, an associate professor in Chinese politics and Asian studies at La Trobe University, pioneers of the hanfu movement have confessed to believing that the issue of Han clothing cannot be separated from the larger issue of racial identity and political power in China. He cites the website Hanwang (Chinese: 漢網, 'Han Network') as an example of their Han supremacist agenda. Launched in 2003, Hanwang's constitution asserted that "Han culture is the world's most advanced and its race is one of the strongest and most prosperous" and endorsed the reintroduction of traditional Han clothing. Nonetheless, Leibold has mentioned that "one would be mistaken in believing that all Hanfu supporters share the political agenda embedded in the Hanwang constitution. Rather, the movement encompasses a very diverse group of individuals who find different sorts of meaning and enjoyment in the category of Han."[5][56]

Eric Fish, a freelance writer who lived in China from 2007 to 2014 as a teacher, student, and journalist, believed that the hanfu movement does have "patriotic undertones" but "most Hanfu enthusiasts are in it for the fashion and community more than a racial or xenophobic motivation". He also mentioned that contrary to popular belief, China's "young people overall are progressively getting less nationalistic".[57]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hanfu movement. |

Notes

- Ying, Zhi (2017). The Hanfu Movement and Intangible Cultural Heritage: considering The Past to Know the Future (MSc). University of Macau/Self-published. p. 12.

- Layton, Robert; Yifei, Luo (2019). Contemporary Anthropologies of the Arts in China. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 195. ISBN 978-1-5275-2092-9. OCLC 1064685784.

- Zhao, Fujia (2018). "On the Educational Significance of Hanfu to Modern Society under the Background of Cultural Rejuvenation". International Journal of Social Science and Education Research. 1 (4): 74–80.

- Yeung, Juni L. (24 May 2016). "The Hanfu Revival Movement in Toronto". Torguqin. Toronto Guqin Society. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- Leibold, James (September 2010). "More Than a Category: Han Supremacism on the Chinese Internet". The China Quarterly. 203: 539–559. doi:10.1017/S0305741010000585.

- Yangzom, Dicky (2014). Clothing and Social Movements: The Politics of Dressing in Colonized Tibet (MSc). City University of New York. p. 38.

- Chew, Matthew Ming-tak (January 2010). "Fashion and society in China in the 2000s: New developments and sociocultural complexities". ResearchGate. ResearchGate. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- Keliher, Macabe (2019). The Board of Rites and the Making of Qing China. Univ of California Press. p. 157. ISBN 0520300297.

- Keliher, Macabe (2019). The Board of Rites and the Making of Qing China. Univ of California Press. p. 158. ISBN 0520300297.

- Keliher, Macabe (2019). The Board of Rites and the Making of Qing China. Univ of California Press. p. 159. ISBN 0520300297.

- Schlesinger, Jonathan (2017). A World Trimmed with Fur: Wild Things, Pristine Places, and the Natural Fringes of Qing Rule. Stanford University Press. p. 25. ISBN 1503600688.

- Chung, Young Yang Chung (2005). Silken threads: a history of embroidery in China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam (illustrated ed.). Harry N. Abrams. p. 148. Retrieved Dec 4, 2009.

- Dusenbury, Mary M.; Bier, Carol. Helen Foresman Spencer Museum of Art (ed.). Flowers, Dragons & Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art (illustrated ed.). Hudson Hills. p. 103. ISBN 1555952380.

- Dusenbury, Mary M.; Bier, Carol. Helen Foresman Spencer Museum of Art (ed.). Flowers, Dragons & Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art (illustrated ed.). Hudson Hills. p. 104. ISBN 1555952380.

- Dusenbury, Mary M.; Bier, Carol. Helen Foresman Spencer Museum of Art (ed.). Flowers, Dragons & Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art (illustrated ed.). Hudson Hills. p. 105. ISBN 1555952380.

- Dusenbury, Mary M.; Bier, Carol. Helen Foresman Spencer Museum of Art (ed.). Flowers, Dragons & Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art (illustrated ed.). Hudson Hills. p. 106. ISBN 1555952380.

- Forsyth, James (1994). A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia's North Asian Colony 1581-1990 (illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 214. ISBN 0521477719.

- Dusenbury, Mary M.; Bier, Carol. Helen Foresman Spencer Museum of Art (ed.). Flowers, Dragons & Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art (illustrated ed.). Hudson Hills. p. 115. ISBN 1555952380.

- Dusenbury, Mary M.; Bier, Carol. Helen Foresman Spencer Museum of Art (ed.). Flowers, Dragons & Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art (illustrated ed.). Hudson Hills. p. 117. ISBN 1555952380.

- Keliher, Macabe (2019). The Board of Rites and the Making of Qing China. Univ of California Press. p. 149. ISBN 0520300297.

- 呤唎 (February 1985). 《太平天國革命親歷記》. 上海古籍出版社.

- Godley, Michael R. (September 2011). "The End of the Queue: Hair as Symbol in Chinese History". China Heritage Quarterly. China Heritage Project, ANU College of Asia & the Pacific (CAP), The Australian National University (27). ISSN 1833-8461.

- Meyer-Fong, Tobie (2013). What Remains: Coming to Terms with Civil War in 19th Century China (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 83. ISBN 0804785597.

- Hang, Xing (2016). Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720. Cambridge University Press. p. 77. ISBN 1316453847.

- Hang, Xing (2016). Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720. Cambridge University Press. p. 86. ISBN 1316453847.

- Hang, Xing (2016). Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720. Cambridge University Press. p. 187. ISBN 1316453847.

- Edward J. M. Rhoads (2000). Manchus and Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861–1928. University of Washington Press. pp. 61–. ISBN 978-0-295-98040-9.

- Twitchett, Denis; Fairbank, John K. (2008) Cambridge History of China Volume 9 Part 1 The Ch'ing Empire to 1800, p87-88

- "Chinese Clothing - Five Thousand Years' History". Culture Essentials Explore Chinese Culture. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- Toby, Ron P. (2019). Engaging the Other: 'Japan' and Its Alter-Egos, 1550-1850. Brill's Japanese Studies Library. BRILL. p. 217. ISBN 900439351X.

- Toby, Ron P. (2019). Engaging the Other: 'Japan' and Its Alter-Egos, 1550-1850. Brill's Japanese Studies Library. BRILL. p. 214. ISBN 900439351X.

- Zhao, Ruixue (2013-06-14). "Dressed like nobility". China Daily.

- "Confucius family's secret legacy comes to light". Xinhua. 2018-11-28.

- Sankar, Siva (2017-09-28). "A school that can teach the world a lesson". China Daily.

- Wang, Guojun (December 2016). "The Inconvenient Imperial Visit: Writing Clothing and Ethnicity in 1684 Qufu". Late Imperial China. Johns Hopkins University Press. 37 (2): 137–170. doi:10.1353/late.2016.0013.

- Kile, S.E.; Kleutghen, Kristina (June 2017). "Seeing through Pictures and Poetry: A History of Lenses (1681)". Late Imperial China. Johns Hopkins University Press. 38 (1): 47–112. doi:10.1353/late.2017.0001.

- Sloane, Jesse D. (October 2014). "Rebuilding Confucian Ideology: Ethnicity and Biography in the Appropriation of Tradition". Sungkyun Journal of East Asian Studies. 14 (2): 235–255. ISSN 1598-2661.

- "Han follow suit in cultural renaissance", Asian Times Online

- "Submission for a Proposal on hanfu dress for the 2008 Chinese Olympics to the China Olympics Committee" Archived 2007-05-15 at the Wayback Machine, Phoenix TV (in Chinese)

- 官方首次表态北京奥运礼服不用汉服 (in Chinese)

- 高, 春明 (1996). 《中國衣冠服飾大辭典》. 上海: 周汛. ISBN 7-5326-0252-4.

- 《宋史》:“吾家世為王民,自金人犯邊,吾兄弟不能以死報國,避難入關,今為曦所逐,吾不忍棄漢衣冠,願死於此,為趙氏鬼。”

- 倪在田 (1957). 《續明紀事本末》 (in Chinese). 臺灣大通書局. p. 214.

“(金)聲桓預作數十棺,全家漢服坐其中,自焚死。”

- 樊綽; 趙吕甫校释 (1985). 《云南志校释》 (in Chinese). 中国社会科学出版社. p. 143页.

“裳人,本漢人也。部落在鐵橋北,不知遷徙年月。初襲漢服,後稍参諸戎風俗,迄今但朝霞纏頭,其余無異。”

- 《馬關縣志·風俗志》.

“男子衣褲用棉布係以腰帶,有鈕扣與漢服略同者,稱之為漢苗”

- 《廣州市黃埔區志》.

“清末民初時期,大多數人都是以穿漢服(唐裝)為主”

- 羅, 雪揮 (2005-09-05). "《「漢服」先鋒》". 《中國新聞周刊》.

- ""汉服运动":互联网时代的种族性民族主义--《中国青年政治学院学报》2009年04期". 2016-08-04. Retrieved 2005-09-01.

- Kevin Carrico, "The Great Han Race, Nationalism, and Tradition in China Today", UC Press, 2017, ISBN 9780520295506

- 华, 梅 (14 June 2007). "汉服堪当中国人的国服吗?". People's Daily Online.

- 週, 星 (2012). "漢服運動:中國互聯網時代的亞文化". ICCS Journal of Modern Chinese Studies. 4: 61–67.

- 周星 (2008). "新唐裝、漢服與漢服運動——二十一世紀初葉中國有關"民族服裝"的新動態". 《開放時代》 (3).

- "Should China Adopt Hanfu as Its National Costume? ", Beijing Review, 10 July 2007

- Yan, Alice (2018). "400 years after falling out of favour, the flowing, and sometimes controversial, robes of the Han ethnic group are back in style". South China Morning Post.

- Kevin Carrico, A State of Warring Styles

- Thomas Mullaney; Eric Armand Vanden Bussche; Stéphane Gros; James Patrick Leibold (2012). Critical Han Studies. Univ of California Press. pp. 40–41. ISBN 9780520289758.

- Gaskin, Sam. "Fantasy, Not Nationalism, Drives Chinese Clothing Revival". The Business of Fashion. Retrieved 29 May 2019.