Grand Alliance (League of Augsburg)

The Grand Alliance is the anti-French coalition formed on 20 December 1689 between England, the Dutch Republic and the Archduchy of Austria. It was signed by the two leading opponents of France; William III, King of England and Stadtholder of the Dutch Republic, and Emperor Leopold, on behalf of the Archduchy of Austria.

Long name:

| |

|---|---|

The architect of the Alliance, William, King of England, Scotland, and Stadtholder of the Dutch Republic | |

| Context | Anti-French Coalition |

| Signed | 20 December 1689 |

| Location | The Hague |

| Parties |

|

With the later additions of Spain and Savoy, this coalition fought the 1688–97 Nine Years' War against France that ended with the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick.

The Second Grand Alliance was reformed by the 1701 Treaty of The Hague prior to the War of the Spanish Succession and dissolved following the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht.

Background

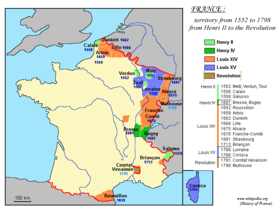

The Grand Alliance was the most significant of the coalitions formed in response to the wars of Louis XIV that began in 1667 and ended in 1714. Post-1648, French expansion was helped by the decline of Spanish power while the Peace of Westphalia formalised religious divisions within the Holy Roman Empire. This weakened the collective security previously provided by the Imperial Circles and led to a series of individual agreements, such as the 1679 Wetterau Union.[lower-alpha 2][2]

Louis XIV secretly supported the Ottomans against the Austrian Habsburgs in the 1683–99 Great Turkish War, while weakening Habsburg influence within the Holy Roman Empire by paying subsidies to states including Bavaria, the Palatinate, Cologne and Brandenburg-Prussia.[3] The Protestant Kingdom of Denmark also received subsidies and when James II became King of England in February 1685, he was viewed as a French ally.[4]

In 1670, France occupied the Duchy of Lorraine, then much of Alsace in the 1683–84 War of the Reunions, threatening Imperial states in the Rhineland. The October 1685 Edict of Fontainebleau revoked tolerance for French Huguenots, an estimated 200,000 – 400,000 of whom left France over the next five years.[5] Former allies like Frederick William now invited French exiles to settle in Brandenburg-Prussia and agreed a treaty with the Dutch Republic in October 1685.[6] These events were followed in 1686 by the massacre of around 2,000 Vaudois Protestants, reinforcing widespread fears that Protestant Europe was threatened by a Catholic counter-reformation led by Louis XIV.[7]

Formation

-en.svg.png)

With Leopold occupied by the Ottomans, William of Orange helped form the anti-French coalition known as the Union of Wetterau, a coalition of German states within the Holy Roman Empire to 'preserve the peace and liberties of Europe.'[8] The Republic was outside the Empire and thus excluded, but many of the Union's leaders were senior Dutch officers, including its head, Georg Friedrich, Prince of Waldeck. He made its most significant innovation; for the first time, members funded a central 'Union' army, rather than providing individual contingents, greatly enhancing its effectiveness.[9]

His model was used for the 1682 Laxenburg Alliance, which grouped Austria with the Upper Rhenish and Franconian Circles to defend the Rhineland but the War of Reunions proved it could not oppose France on its own.[10] When Philip William inherited the Palatinate in May 1685, Louis claimed half of it, based on the marriage of Elizabeth Charlotte of the Palatinate to Philippe of Orléans, creating another crisis.[11]

Victory over the Ottomans at the Battle of Vienna in 1683 allowed Leopold to refocus on the western portions of the Empire. The League of Augsburg was formed in July 1686 by combining the Laxenburg Alliance with the Burgundian Circle, Swedish Pomerania and Bavaria.[12]

On 27 September 1688, French forces invaded the Rhineland and attacked Philippsburg, launching the Nine Years' War. The coalition was strengthened when the Glorious Revolution deposed James II in November 1688 and William of Orange became William III/II of England and Scotland. The Dutch Republic declared war on France in March 1689, followed by England in May.[13]

Membership; League of Augsburg v Grand Alliance

The overlap between the various coalitions is often confusing. The Empire contained hundreds of members, each belonging to an Imperial Circle (see map), an administrative unit for collecting taxes and mutual support; the Swabian Circle alone had over 88 members. Individual states could form or join alliances, such as the 1685 agreement between Brandenburg-Prussia and the Dutch Republic, while Leopold signed the Grand Alliance as Archduke of Austria.[14] However, only the Imperial Diet could commit the entire Empire; unlike the 1701–14 War of the Spanish Succession, the Nine Years' War was not declared an 'Imperial' one.[15]

A number of foreign monarchs became personally involved, because they held titles and lands within the Empire. Sweden was technically neutral, but Charles XI of Sweden was also Duke of Swedish Pomerania, a member of the Lower Saxon Circle and part of the League. The same applied to the Spanish Netherlands, a member of the Burgundian Circle, but not the Kingdom of Spain, which joined the Grand Alliance in 1690.[16]

Lastly, some writers fail to differentiate between the Grand Alliance, ie England, the Dutch Republic, Spain and Austria, and the wider anti-French 'alliance,' which included German states like Bavaria, the Palatinate, etc. European diplomacy was extremely hierarchical; the Grand Alliance acknowledged the Dutch Republic and England as Leopold's equals, a status he guarded with great care. This made the later admission of Savoy a major triumph for Victor Amadeus, but Leopold refused to allow Bavaria and Brandenburg-Prussia separate representation at the Ryswick peace talks in 1697.[17]

Provisions

The terms of the Grand Alliance were largely based on the agreements of May 1689 between the Dutch Republic and Austria and the August 1689 Anglo-Dutch 'Treaty of Friendship and Alliance.'[18] It was finally signed on 20 December 1689, delayed by Leopold's concerns on accepting William as King of England, and the impact on English Roman Catholics.[19]

The main provisions were to ensure restoration of the borders agreed at Westphalia in 1648, the independence of the Duchy of Lorraine and French recognition of the Protestant Succession in England. Signatories also bound themselves not to agree a separate peace; failure to keep this commitment had greatly improved the French position during negotiations over the 1678 to 1679 Treaties of Nijmegen.[20]

What would happen when the childless Charles II of Spain died featured in many agreements of the period, including the 1670 Secret Treaty of Dover between England and France. A secret clause now committed England and the Dutch Republic to support Leopold's claims to the Spanish throne, an undertaking that would lead to another war.[21]

Aftermath

The main area of conflict was in the Spanish Netherlands, with the Dutch doing much of the fighting; Habsburg forces were occupied by a renewed Ottoman offensive in South-East Europe, while the War in Ireland absorbed resources in England and Scotland until 1692. The entry of Spain and Savoy opened new fronts in Catalonia and Northern Italy but both required support by Allied-funded German auxiliaries.[22]

The purpose of the Grand Alliance was to resist French expansion, the legality of Louis' claims in the Palatinate being less important than their impact on the balance of power. Its creation also highlighted the obsolescence of the Imperial Circles and ultimately larger, more centralised states, including Brandenburg-Prussia, Bavaria and Saxony. This makes it a significant milestone in developing the concept of collective security, the fundamental issue at stake in the War of the Spanish Succession.[23]

The Nine Years' War was financially crippling for participants; the average army size increased from 25,000 in 1648 to over 100,000 by 1697, a level unsustainable for pre-industrial economies. Between 1689 and 1696, 80% of English government revenues were spent on the military, with one in seven adult males serving in the army or navy; figures were similar or worse for other combatants.[24]

By 1693, both sides recognised decisive victory was no longer possible and France began informal peace talks with Dutch and Savoyard representatives. In August 1696, France and Savoy agreed a separate peace in the Treaty of Turin. Wider talks made little progress as Leopold demanded the restoration of all Imperial losses in the Rhineland since 1667, and an agreement on the Spanish succession; until then, he held his Allies to their commitment not to make a separate peace.[25] The Treaty of Ryswick was finalised once France agreed to return Luxembourg to Spain, and Louis set aside his personal commitment to James by recognising William as King. Despite this, Leopold signed with great reluctance in October 1697.[26]

Leopold was correct in that failure to resolve this question led to the War of the Spanish Succession in 1701, but the English and Dutch felt his demands were extending a hugely expensive war for objectives of little benefit to them. Studies show English trade with Southern Europe alone declined by over 25% between 1689 and 1693, while the French capture of over 90 merchant ships at Lagos in 1693 caused massive financial losses in London and Amsterdam.[27]

The result was the City of London and English Tories strongly opposed spending money on European wars, rather than the Royal Navy.[28] This had a long-lasting impact on English attitudes; in 1744, James Ralph began his chapter on the Nine Years' War as follows; 'The moment he (William) became sovereign, he made the Kingdom subservient to the Republic; in war, we had the honour to fight for the Dutch; in negotiation, to treat for the Dutch; while the Dutch had all possible encouragement to trade for us...'.[29]

Footnotes

- Savoy made a separate peace with France in 1696.

- The list of members illustrates the fragmented nature of the Empire; the ten original members were the Counts of Stollberg, Westerburg, most branches of the House of Nassau, plus Hanau, Solms, Isenburg, Wied, Wittgenstein, Waldeck, and Manderscheid. Later additions included Hessen-Kassel, Cologne, Fulda, Hessen-Darmstadt, Schwarzburg, Gotha, Eisenach and Würzburg.[1]

References

- Maass 2017, p. 66.

- Maass 2017, p. 68.

- Nolan 2017, p. 116.

- Meerwijk 2011, p. 9.

- Spielvogel 2014, p. 410.

- Stapleton 2003, p. 63.

- Bosher 1994, pp. 6-8.

- Rommelse & Onnekink 2016, pp. 283-284.

- Stapleton 2003, pp. 61-62.

- Young 2004, p. 218.

- Troost 2005, p. 175.

- Young 2004, p. 220.

- Childs 1991, pp. 21-22.

- Hochedlinger 2003, p. 169.

- Wolf 1968, p. 514.

- Meerwijk 2011, p. 39.

- Hochedlinger 2003, p. 107.

- Stapleton 2003, pp. 84–85.

- Meerwijk 2011, pp. 20-22.

- Troost 2005, p. 242.

- Hochedlinger 2003, p. 171.

- Young 2004, p. 232.

- Lesaffer.

- Childs 2013, p. 1.

- Young 2004, p. 233.

- Szechi 1994, p. 51.

- Aubrey 1979, pp. 157-159.

- Rommelse & Onnekink 2016, pp. 35-36.

- Ralph 1744, p. 1023.

Sources

- Aubrey, TP (1979). The Defeat of James Stuart's Armada 1692. Leicester University Press. ISBN 978-0718511685.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Bosher, JF (February 1994). "The Franco-Catholic Danger, 1660–1715". History. 79 (255): 5–30. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.1994.tb01587.x. JSTOR 24421929.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Childs, John (1991). The Nine Years' War and the British Army, 1688-1697: The Operations in the Low Countries. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0719089961.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- "The City of London's strange history". Financial Times. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Hochedlinger, Michael (2003). Austria's Wars of Emergence, 1683-1797. Routledge. ISBN 978-0582290846.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Lesaffer, Randall. "The peace of Utrecht and the balance of power". OUP Blog. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- Maass, Mathias (2017). Small States in World Politics: The Story of Small State Survival, 1648-2016. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0719082733.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Meerwijk, MB (2011). Negotiating the Grand Alliance; the role of the King-Stadtholder’s corps diplomatique in establishing a new alliance between ‘Austria’, the Dutch Republic and England, 1688 - 1690 (PhD). Utrecht University.

- Nolan, Cathal (2017). The Allure of Battle: A History of How Wars Have Been Won and Lost. OUP. ISBN 978-0195383782.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Ralph, James (1744). The History of England. Coogan & Waller.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Rommelse, Gijs; Onnekink, David, eds. (2016). Ideology and Foreign Policy in Early Modern Europe (1650–1750). Routledge. ISBN 978-1138278820.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Spielvogel, Jackson J (1980). Western Civilization. Wadsworth Publishing. ISBN 978-1285436401.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Stapleton, John M (2003). Forging a Coalition Army; William III, the Grand Alliance and the Confederate Army in the Spanish Netherlands 1688-97 (PhD). Ohio State University.

- Szechi, Daniel (1994). The Jacobites: Britain and Europe, 1688–1788. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0719037740.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Troost, Wouter (2005). William III the Stadholder-king: A Political Biography. Routledge. ISBN 978-0754650713.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

- Wolf, John (1968). Louis XIV (1974 ed.). WW Norton & Co. ISBN 978-0393007534.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Young, William (2004). International Politics and Warfare in the Age of Louis XIV and Peter the Great. iUniverse. ISBN 978-0595329922.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link);

External links

- Lesaffer, Randall. "The peace of Utrecht and the balance of power". OUP Blog. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- "The City of London's strange history". Financial Times.