Economic consequences of population decline

Population decline has many potential effects on individual and national economy. The single best gauge of economic success is growth in GDP per person, not total GDP.[1][2] GDP per person is a rough proxy for average living standards, for individual prosperity.[3] Therefore, whether population decline has a positive or negative economic impact on a country’s citizens depends on the rate of growth of GDP per person, or alternatively, GDP growth relative to the rate of decline in the population.[1]

Introduction

The simplest expression for the size of a country’s economy is

GDP = total population x GDP/person[4]

GDP/person is also known as GDP per capita or per capita GDP. This term is a simple definition of economic productivity as well as individual standard of living.

The real change in total GDP is defined as the change in population plus the real change in GDP/capita.[4] The table below shows that historically, for every major region of the world, both of these have been positive. This explains the enormous economic growth around the world brought on by the industrial revolution. However, the two columns on the right also show that, for every region, population growth in the future will decline and, in some regions, go negative. The chart also shows that two major economies, Japan and Germany, may face the same conditions.

| 1820 - 2010[4] - - - - - - - - - - - | 2015-20 | 2040-45 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop | GDP/cap | GDP | Pop[5] | Pop[6] | ||

| Western Europe | 0.60 | 1.40 | 2.00 | 0.42 | -0.07 | |

| Eastern Europe | 0.62 | 1.21 | 1.83 | -0.09 | -0.41 | |

| Former USSR | 0.87 | 1.11 | 1.98 | na | na | |

| Western Offshoots* | 1.84 | 1.64 | 3.48 | |||

| North America | 0.65 | 0.38 | ||||

| Latin America | 1.75 | 1.25 | 3.00 | 0.94 | 0.32 | |

| Asia | 0.93 | 1.25 | 2.18 | 0.92 | 0.25 | |

| Africa | 1.38 | 0.75 | 2.13 | 2.51 | 1.88 | |

| World | 0.99 | 1.26 | 2.25 | 1.09 | 0.61 | |

| Germany | 0.48 | -0.21 | ||||

| Japan | -0.24 | -0.69 | ||||

* Western Offshoots are the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand

Because

GDP = total population x GDP/person,

as populations grow more slowly, assuming no changes in growth of GDP/person, GDP will also grow more slowly.

If per capita GDP increase is less than the decrease in total population.

The equation above shows that if the decline in total population is not matched by an equal or greater increase in productivity (GDP/capita), and if that condition continues from one calendar quarter to the next, it follows that a country would experience a decline in GDP, known as an economic recession. If these conditions become permanent, the country could find itself in a permanent recession.

The possible impacts of a declining population that leads to permanent recession are:

- Decline in Basic Services and infrastructure. If the GDP of a community declines, there is less demand for basic services such as hotels, restaurants and shops. The employment in these sectors then suffers.[7] A falling GDP also implies a falling tax base that would support basic infrastructure such as police, fire and electricity. The government may be forced to abandon some of this infrastructure, like bus and railroad lines, and combine school districts, hospitals and even townships in order to maintain some level of economies of scale.[8]

- Rise in dependency ratio. Dependency ratio is the ratio of those not in the labor force (the dependent part ages 0 to 14 and 65+) and those in the labor force (the productive part ages 15 to 64). It is used to measure the pressure on the productive population. Population decline caused by sub-replacement fertility rates means that every generation will be smaller than the one before it. Combined with longer life spans the result can be an increase in the dependency ratio which can put increased economic pressure on the work force. With the exception of Africa, dependency ratios are forecast to increase everywhere in the world by the end of the 21st century.

- Crisis in end of life care for the elderly. A falling population caused by sub-replacement fertility and/or longer life spans means that the growing size of the retired population relative to the size of the labor force, known as population ageing, may cause a crisis in end of life care for the elderly because of insufficient caregivers for them.[9]

- Difficulties in funding entitlement programs. Population decline can impact the funding for programs for retirees if the ratio of working age population to the retired population declines. For example, in Japan, there were 5.8 workers for every retiree in 1990 vs 2.3 in 2017 and a projected 1.4 in 2050.[10] Also, according to new research (2019) China’s main state pension fund will run out of money by 2035 as the available workforce shrinks due to effects of that country’s one-child policy.[11] With the exception of Africa, this trend prevails, to a greater or lesser extent, everywhere else in the world.

- Decline in Military Strength. Big countries, with large populations, assuming technology and other things being equal, tend to have greater military power than small countries with small populations. In addition to lowering working age population, population decline will also lower the military age population, and therefore military power.[8]

- Decline in innovation. A falling population also lowers the rate of innovation, since change tends to come from younger workers and entrepreneurs.[10]

- A Strain on Mental Health. Population decline may harm a population’s mental health (or morale) if it causes permanent recession and a concomitant decline in basic services and infrastructure.[12]

- Deflation. A recent (2014) study found substantial deflationary pressures from Japan’s ageing population.[13]

If per capita GDP increase is greater than the decrease in total population.

The single best gauge of economic growth is growth in GDP per person, not total GDP.[1] GDP/person is a rough proxy for average living standards, for individual prosperity.[3] A country can increase its average living standard even though its population growth is low or even negative.

Consider for example Japan. During the period 2003-2007 Japan had a higher growth per capita than the United States, even though the U.S. GDP growth was higher than Japan's.[1] In the United States, the relationship between population growth and growth per capita has been found to be empirically insignificant.[14] Even when GDP growth is zero or negative, the GDP growth per capita can still be positive (by definition) if the population is shrinking faster than the GDP.

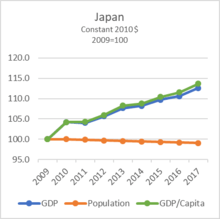

Updating this analysis (the table below) to a more recent time period, 2009-2017, finds the same result. Even though Japan’s population declined 0.9% over this time period, because its per capita GDP, a rough proxy for the standard of living of the average Japanese citizen, rose by about 13.8%, a much greater increase than the 0.9% decrease in its population, its GDP still grew by 12.7%.

| Comparing economic growth, Japan vs US | ||||||

| 2009 | 2017 | % chg | % chg/yr | |||

| Japan[15] | ||||||

| GDP/Cap (thousands 2010 $) | 42.7 | 48.6 | 13.8 | 1.6 | ||

| Pop (millions) | 128.0 | 126.8 | -0.9 | -0.1 | ||

| GDP (trillions 2010 $) | 5.5 | 6.2 | 12.7 | 1.5 | ||

| US[16] | ||||||

| GDP/Cap (thousands 2010 $) | 47.6 | 53.1 | 11.6 | 1.4 | ||

| Pop (millions) | 306.8 | 325.7 | 6.2 | 0.8 | ||

| GDP (trillions 2010 $) | 14.6 | 17.3 | 18.5 | 2.1 | ||

Over the same period, US GDP grew 18.5%. Although this GDP growth rate is greater than Japan’s, mostly because the US population also grew 6.2%, US per capita GDP grew 11.6%, less than the Japanese rate. Therefore, during this period, even though its population declined, the standard of living of the average Japanese citizen grew a little faster than that of the average American.

The charts to the right show the comparison.

The projection for Japan’s population decline will accelerate to reach about -0.7% per year in the 2040-2045 time period. This means that for Japan’s GDP to grow during that period, per capita GDP growth must be at least greater than 0.7% per year.

This example of Japan during the period 2009-2017 shows that a nation can grow its economy and the standard of living of its citizens even though its population is declining.[1] To do this it must grow its per capita GDP, its overall economic productivity, faster than its population declines. Analysis of data for forty countries shows that while low fertility will indeed challenge government programs and very low fertility undermines living standards, moderately low fertility and population decline favor the broader material standard of living.[17]

References

- "Grossly Distorted Picture". The Economist. May 13, 2008.

- "Solving the paradox". The Economist. September 23, 2000.

- Roser, Max (2019). "Economic Growth". Our World In Data.

- Peterson, E. Wesley (Oct 11, 2017). "The Role of Population in Economic Growth". Sage Open. 7 (4): 215824401773609. doi:10.1177/2158244017736094.

- "World Population Prospects 2019, Population Growth Rate, Estimates". United Nations Population Division. 2019.

- "World Population Prospects 2019, Population Growth Rate, Medium Variance". United Nations Population Division. 2019.

- Wallace, P.J. (August 1972). "The Causes and Consequences of Rural Depopulation: Case Studies of Declining Communities" (PDF). US Department of Health Education and Welfare.

- Coleman, David (Jan 25, 2011). "Who's afraid of population decline? A critical examination of its consequences". CiteSeerX 10.1.1.702.6098. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Kim, Tammy (Feb 9, 2018). "Americans Will Struggle to Grow Old at Home". Bloomberg Businessweek.

- Kotkin, Joel (Feb 1, 2017). "Death Spiral Demographics: The Countries Shrinking The Fastest". Forbes.

- Tang, Frank (Apr 12, 2019). "China's state pension fund to run dry by 2035 as workforce shrinks due to effects of one-child policy, says study". South China Morning Post.

- Zivkin, K (2011). "Economic downturns and population mental health: research findings, gaps, challenges and priorities". Cambridge University Press.

- Anderson, Derek (August 4, 2014). "Is Japan's Population Aging Deflationary?". International Monetary Fund.

- Florida, Richard (Sep 30, 2013). "The Great Growth Disconnect: Population Growth Does Not Equal Economic Growth". Citylab.

- "Development Indicators for Japan". The World Bank, Databank, World Development Indicators.

- "Development Indicators for USA". The World Bank, Databank, World Development Indicators.

- "Is Low Fertility Really a Problem?". National Transfer Accounts. 2014.