Dov Charney

Dov Charney (born 31 January 1969) is a Canadian businessman. He is best known for founding American Apparel, where he served as the CEO from 1989 until 2014. He later founded Los Angeles Apparel. He is also an advocate for immigration reform in the United States.[1][2]

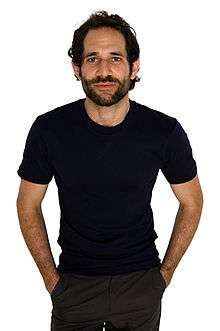

Dov Charney | |

|---|---|

Dov Charney in 2008 | |

| Born | 31 January 1969 |

| Occupation | Apparel Manufacture |

Early life

Charney was born in Montreal, Quebec. His father is an architect, and his mother an artist.[3] Charney is a nephew of architect Moshe Safdie.[4] He attended Choate Rosemary Hall, a private boarding school in Connecticut[5] and St. George's School of Montreal.[6] According to Charney, he was heavily influenced by both Montreal culture and his own Jewish heritage.[4][7]

American Apparel

Charney began making basic T-shirts under the American Apparel brand as early as 1991. By 1997, he moved all manufacturing into an 74,000 m2 (800,000 sq ft) factory located in downtown Los Angeles.[8] American Apparel products were marketed towards "young metropolitan adults."[9] The basic, logo-free branding appealed to younger consumers wary of corporate branding.[10] Eventually, Charney opened over 180 American Apparel retail locations in a total of 13 countries: United States, Canada, England, France, Germany, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Mexico, the Netherlands, Sweden and Switzerland. There were also distribution facilities in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, and Düsseldorf, Germany.

American Apparel under Charney's leadership was known for its simple and provocative ads, which rarely used professional models and whom were often chosen personally by Charney from local hangouts and stores.[11] He shot many of the advertisements himself.[12] His advertising was criticized for featuring young, even teenage, models in sexually provocative poses. However, it was also lauded for honesty and lack of airbrushing.[13][14]

In 2005, Charney won the "Marketing Excellence Award" in the LA Fashion Awards.[15] Charney was also named Retailer of the Year at the Michael Awards in 2008.[16] The award had previously been awarded to Calvin Klein and Oscar de la Renta.[17]

In December 2006, American Apparel entered into a reverse merger agreement valued at $360 million with the special purpose acquisition company (SPAC) Endeavor Acquisition as a way of taking the company public.[18]

Dismissal

American Apparel publicly suspended Charney on 18 June 2014, stating that they would terminate him for cause in 30 days.[19][20] The company's board claimed at the time that it had "new information" which led it to fire Charney. New co-chairman Allan Mayer said: "We have heard for years allegations and rumors in newspaper stories that were not sufficient to take action. But what came to our attention was not allegations and rumors but established fact." He declined to elaborate at that time. The board had just begun an investigation into how Charney responded to a 2011 lawsuit by a former employee who claimed he had held her against her will as a "sex slave", a suit settled in arbitration.[21]

Two days later, a company insider posted a "confession" to the social network Whisper asserting that the reasons for Charney's dismissal were "purely financial ... Everything else is bullshit. The board has nothing new." BuzzFeed got in touch with the poster through Whisper and was able to obtain the board's dismissal letter to Charney. It repeated the board's earlier allegation that he had allowed a subordinate to pose as Irene Morales on a blog and make sexually provocative posts to him, which had apparently led to major punitive damages awarded to Morales by the arbitrator, calling this a breach of his fiduciary duty. Further in that vein, the board said, it had learned of an attempt to possibly suborn perjury in a "pending litigation matter". The letter also charged Charney with misusing corporate assets for personal gain, such as paying lucrative severance packages, bonuses and salary increases in exchange for silence from putative accusers as well as using corporate apartments himself and buying travel for family members with company funds, violating company policy by refusing to attend mandatory sexual harassment training sessions and interrupting them when others attended.[22]

As a result of Charney's behaviour the company's costs had increased unacceptably. "The company's employment practices liability insurance retention has grown to $1 million from $350,000 ... the premiums for this insurance are well outside of industry standards." His reputation had also hurt American Apparel's financing, as "many financing sources have refused to become involved with American Apparel as long as you remain involved with the company" and those that did had imposed "a significant premium for that financing in significant part because of your conduct." It gave him the 30-day suspension to "effect a cure" for these issues.[22] Charney demanded the board reinstate him, threatening to sue.[23]

In December 2014, Charney was terminated as a Chief Executive Officer after months of suspension. He was replaced by Paula Schneider, president of ESP Group Ltd, company of brands like English Laundry, on 5 January 2015.[24] In December 2014, Charney told Bloomberg Businessweek he was down to his last $100,000 and that he was sleeping on a friend's couch in Manhattan.[25] Following his suspension as CEO in the summer of 2014, Charney teamed up with the Standard General hedge fund to buy stocks of the company to attempt a takeover.[26]

In 2016, American Apparel board dismissed a $300 million offer from Hagan Group that pushed for Charney's comeback.[27]

Los Angeles Apparel

In 2016, Charney founded Los Angeles Apparel. Following the launch, his new apparel company was frequently compared to American Apparel, with a number of reporters stating the similarities between the strategies of the two companies.[28] He opened Los Angeles Apparel's first factory in South Central Los Angeles, with aims of replicating the successes he experienced in the 1990s with supplying wholesale clothing. The strategy was similar to that he deployed while expanding American Apparel. This included manufacturing all the garments in the US to keep lead times low and offer better completion times than overseas competitors.[29] The company grew to over 350 staff during the second year of operation. During an interview with Bloomberg, Charney drew comparisons to the growth he experienced with American Apparel calling it the equivalent of "year eight". Charney expected the fashion line to grow to $20 million in revenue by 2018.[29]

Following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, Charney repurposed his business operations to help increased demand for PPE (Personal Protective Equipment).[30] According to the Los Angeles Times, Charney spotted shortages as early as February and this is when his apparel company began to consider manufacturing face masks.[31]

Charney was interviewed in March 2020 by a number of media outlets, speaking about his desire to turn Los Angeles Apparel into a medical equipment manufacturer during the pandemic. Los Angeles Apparel then began manufacturing face masks and medical gowns at the facility in South Central. Charney told the New York Times that he aimed to create 300,000 masks and 50,000 gowns each week.[32] Los Angeles Apparel launched the new face mask in over a dozen different colors. In an interview, Charney said he was "losing money on the venture," as he was giving many of them away.[33] This included donating large numbers to key workers in healthcare and law enforcement in LA, Seattle, New York City and Las Vegas.[31]

Activism

Under Charney's leadership, American Apparel took a leading role in the promotion of a number of prominent social causes.

Legalize LA

Legalize LA was an immigration reform campaign conceived by Charney and promoted by American Apparel beginning in 2004. The campaign featured billboards and full-page ads in national publications as well as t-shirts sold in retail locations emblazoned with the words "Legalize LA." Proceeds from the sale of the shirts were donated to immigration reform advocacy groups. The campaign called for the overhaul of immigration laws so as to create a legal path for undocumented workers to gain citizenship in the United States.[34][35]

Legalize Gay

In November 2008, after the passing of Proposition 8, which banned same-sex marriages in California, Dov Charney and American Apparel created "Legalize Gay" T-shirts to hand out to protesters at rallies. The positive reaction led American Apparel to sell the same shirts in stores and online.[36]

Factory conditions

In an interview with Vice.tv, Charney spoke out against the poor treatment of fashion workers in developing countries and refers to the practices as "slave labor" and "death trap manufacturing". Charney proposed a "Global Garment Workers Minimum Wage" and discussed in detail many of the inner workings of the modern fast fashion industry practices that creates dangerous factory conditions and disasters like the 2013 Savar building collapse on May 13, which had the death toll of 1,127 and 2,500 injured people who were rescued from the building alive.[37]

Controversy

Charney has been the subject of several sexual harassment lawsuits, at least five since the mid-2000s, all of which were settled, dismissed, or remanded to private arbitration.[38][39][40][41][42] He has never been found to have committed sexual harassment.[43] Charney's lawyer, Keith Fink, told Business Insider that, "In many instances, cases were defeated or dismissed. In other instances, cases were settled because the insurance company whose only goal is to save total dollars wanted to stop the legal bleeding on these cases."[43]

Charney maintained his innocence, telling CNBC that "allegations that I acted improperly at any time are completely a fiction."[44] The company and independent media outlets publicly accused lawyers in the lawsuits against American Apparel of extortion and of "shaking the company down."[45][46][47][48][49][50]

In 2004, Claudine Ko of Jane magazine[51] published an essay narrating that he began masturbating in front of her while she was interviewing him.[13][52][53][54] The article's publication brought extensive press to the company and Charney, who later responded that he believed that the acts had been done consensually, in private and outside the article's bounds.[55][56][57][58]

Personal life

Charney lives in the Garbutt House, a historic mansion atop a hill in Silverlake designed by Frank Garbutt, an early movie pioneer and industrialist.[45] The home is made entirely out of concrete due to Garbutt's fear of fire. The house often functions as a dormitory for out-of-town workers doing business at company headquarters.[45] During his time at American Apparel Charney was consumed with work, often sleeping in his office at the company's factory, leaving little separation between his personal and work life.[45]

References

- Joellen Perry; Marianne Lavelle (16 May 2004). "Made in America". U.S. News and World Report. Retrieved 27 November 2007.

- Barco, Mandalit Dell. "American Apparel, an Immigrant Success Story". NPR. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- Jewish Journal, Unfashionable Crisis, 29 July 2005.

- Silcoff, Mireille. "A real shirt-disturber: Dov Charney conquered America with his fitted t-shirts and posse of strippers". Saturday Post. Archived from the original on 6 May 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2008.

- Haskell, Kari (18 September 2006). "An Interview With American Apparel Founder Dov Charney". Debonair Magazine. Archived from the original on 6 April 2008. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- St. George Alumni Archived 22 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Morissette, Caroline (1 April 2005). "Dov Charney at McGill". Bull and Bear. Archived from the original on 4 February 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- "Segment of Modern Marvels: Cotton". The History Channel via AmericanApparel.net. Archived from the original on 21 December 2007. Retrieved 25 November 2007.

- Jamie Wolf (23 April 2006). "And You Thought Abercrombie & Fitch Was Pushing It?". New York Times Magazine. Retrieved 25 November 2007.

- La Ferla, Ruth (3 November 2004). "Building a Brand By Not Being a Brand". New York Times. Retrieved 21 March 2008.

- Rapoport, Adam (June 2004). "T (Shirts) and A". GQ. "What makes American Apparel's female models so appealing is that most of them are not models. They are girls whom Charney meets at bars, restaurants, trade shows—pretty much anywhere."

- Palmeri, Christopher (27 June 2005). "Living on the Edge at American Apparel". Businessweek. Archived from the original on 24 March 2008. Retrieved 22 March 2008. "Charney takes many of the photos himself, often using company employees as models as well as people he finds on the street."

- Stossel, John (2 December 2005). "Sexy Sweats Without the Sweatshop". ABC News. Retrieved 21 March 2008.

- Morford, Mark (24 June 2005). "Porn Stars in My Underwear". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 10 March 2008. Retrieved 21 March 2008.

- "LA Fashion Awards". LA Fashion Awards. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- American Apparel CEO Named Retailer of the Year 9 June 2008. "I am privileged to accept this award in recognition of the hard work and creativity of the many people who have contributed to American Apparel's rapid growth and success". Archived 27 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Fashionista: Dov Charney, Winner Archived 4 July 2008 at Archive.today "Dov Charney was recently named "Retailer of the Year" for his work as the Creative Director and entrepreneur behind American Apparel.

- Kang, Stephanie (19 December 2006). "American Apparel Seeks Growth Through An Unusual Deal". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 21 March 2008.

- "Welcome mid-marketpulse.com - BlueHost.com". Mid-marketpulse.com. Archived from the original on 18 November 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- Riley, Charles (19 June 2014). "American Apparel fires controversial CEO". CNN Money. Retrieved 19 June 2014.

- Covert, James (20 June 2014). "'Sex slave' led to ouster of American Apparel CEO". The New York Post. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- Maheshwari, Sapna (22 June 2014). "Exclusive: Read Ousted American Apparel CEO Dov Charney's Termination Letter". BuzzFeed. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- Li, Shan; Chang, Andrea (22 June 2014). "Dov Charney demands American Apparel job back or he'll sue, says lawyer". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- Dastin, Jeffrey (16 December 2014). "American Apparel names new CEO, officially ousts founder". Reuters. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- Coleman-Lochner, Lauren (22 December 2014). "American Apparel Founder Says He's Down to Last $100,000". Bloomberg.

- Peterson, Hayley. "Ousted American Apparel CEO Dov Charney Claims He Was Robbed By A Hedge Fund". Business Insider. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- "What happened when Dov Charney tried to get American Apparel back". The Independent. 15 January 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- Feldman, Ari (13 July 2017). "Dov Charney Is Remaking American Apparel. Can He Remake Himself?". Forward.com.

- Townsend, Matthew (12 July 2017). "Dov Charney Couldn't Keep American Apparel, So He Restarted It". Bloomberg.

- "How your business can help fight coronavirus: One brand's pivot to making masks". FastCompany. 23 March 2020.

- Schmidt, Ingrid (24 March 2020). "Fashion brands are making face masks, medical gowns for the coronavirus crisis". Los Angles Times.

- Testa, Jessica (21 March 2020). "Christian Siriano and Dov Charney Are Making Masks and Medical Supplies Now". New York Times.

- Pierce, Tony. "Dov Charney's New Passion: Face Masks". Los Angeleno.

- Story, Louise (18 January 2008). "Politics Wrapped in a Clothing Ad". The New York Times.

- "American Apparel takes stand on immigration". Reuters. 28 October 2008.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved 23 June 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- VICE (29 May 2013). "Dov Charney on Modern Day Sweat Shops: VICE Podcast 006". YouTube. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- Holson, Laura M. (23 March 2011). "Dov Charney of American Apparel Named in Harassment Suit". The New York Times.

- Covert, James (28 March 2010). "American Apparel Struggles to Stay Afloat". New York Post. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- Brennan, Ed (18 May 2009). "Woody Allen reaches $5m settlement with head of American Apparel". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 22 May 2009. Quote: "Charney has been involved in several highly-publicised sexual harassment suits brought by former employees, none of which were proven."

- Sefton, Eliot (3 September 2009). "Dov Charney's LA-based clothing company loses 1,600 staff and sees yet another advert banned". The First Post. Archived from the original on 8 September 2009. Retrieved 11 September 2009.

Charney has been the subject of several, unproven, sexual harassment suits and claims to have been victimised by the media in the past. He said that he used Woody Allen in his company's ads because he wanted to draw attention to the way he and Allen – both high-profile Jews – had been treated.

- "American Apparel CEO Dov Charney's 'Sex Slave' Lawsuit Thrown Out". The Huffington Post. 22 March 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- Biron, Bethany (22 August 2019). "15 brands that are surprisingly not American, from Burger King to American Apparel". Business Insider. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- American Apparel CEO: Tattered, but Not Torn Archived 20 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine CNBC.com Jane Wells 4/10/12 "The company is also trying to recover from a litany of lawsuits against Charney, including a sex slave lawsuit that was thrown out last month"

- Holson, Laura (13 April 2011). "He's Only Just Begun to Fight". THe New York Times. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- Heller, Matthew (28 October 2008). "Fashion Mogul 'Fakes' Arbitration in Harassment Case". On Point. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

The 'confidential arbitration' was in fact a charade. One of Nelson's attorneys, the 2nd District said, later described it as 'a 'fake arbitration' designed to produce a press release calculated to blunt negative media attention.'

- Slater, Dan (4 November 2008). "The Story Behind American Apparel's Sham Arbitration". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 5 November 2008.

The court went on to say that 'the proposed press release is materially misleading — among other things, no real arbitration of a dispute occurred and [the] plaintiff received $1.3 million in compensation.'

- Stein, Sadie (31 October 2008). "Tangled Webs: Dov Charney's Court Case is Totally Complicated". Jezebel. Retrieved 4 November 2008.

In response, Ms. Nelson's lawyer, Mr. Fink, devised a settlement agreement whereby his client would agree to certain stipulations amounting to a confession that her charges of sexual harassment were bogus, and that she had never been subject to any harassment or a hostile work environment.

- Nolan, Hamilton (April 2011). "American Shakedown? Sex, Lies and the Dov Charney Lawsuit". Gawker. Archived from the original on 2 May 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- "Ex-workers say American Apparel posted nude pix online". Reuters. April 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- Nesvig, Kara (4 October 2007). "Unkempt, Urban, Ubiquitous". Minnesota Daily. Archived from the original on 20 April 2008. Retrieved 28 April 2008. Archived at americanapparel.net Archived 18 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Sexy marketing or sexual harassment? - Dateline NBC | NBC News". NBC News. 28 July 2006. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- "'Jewish hustler'—potty mouth and pervert—means no offense | The God Blog". Jewish Journal. 3 June 2008. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- "american apparel". Claudinenko.com. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- "The company calls it "a social situation which...unfortunately was exploited in order to sell magazines." American Apparel CEO Trial Starts Today Archived 15 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine CNBC. Margaret Brennan. 28 February 2008.

- "I've never done anything sexual that wasn't consensual", Charney says. The reporter, Claudine Ko, confirmed his take on events to BusinessWeek." Living on the Edge at American Apparel

- "Within the context of a flirtatious conversation about sexuality and the pleasure Charney derives from masturbation with a willing partner, he decided to demonstrate for Ko, and it became a repeated motif in their later encounters. The article left a lasting impression of him as a boss who can't keep it in his pants", The New York Times "And You Thought Abercrombie and Fitch Was Pushing It"

- "I was a younger man" he says, wearily. "The lines were blurred between paramour and reporter." The reporter has said that her tape recorder or notebook was in full view at all times and that the relationship was professional." Portfolio profile of Charney Archived 20 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Dov Charney |