European early modern humans

"European early modern humans" (EEMH) is a term for the earliest populations of anatomically modern humans in Europe, during the Upper Paleolithic. It is taken to include fossils from throughout the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), covering the period of about 48,000 to 15,000 years ago (48–15 ka), spanning the Bohunician, Aurignacian, Gravettian, Solutrean and Magdalenian periods.

The term EEMH is equivalent to Cro-Magnon Man, or "Cro-Magnons", a term derived from the Cro-Magnon rock shelter in southwestern France, where the first EEMH were found in 1868. Louis Lartet (1869) proposed Homo sapiens fossilis as the systematic name for "Cro-Magnon Man". W. K. Gregory (1921) proposed the subspecies name Homo sapiens cro-magnonensis. In literature published since the late 1990s, the term EEMH is generally preferred over the common name Cro-Magnon, which has no formal taxonomic status, as "it refers neither to a species or subspecies nor to an archaeological phase or culture".[note 1] Use of "Cro-Magnon" is mostly restricted to times after the beginning of the Aurignacian proper, c. 37 to 35 ka.[1]

The oldest known EEMH fossil remains are found in Bacho Kiro cave, Bulgaria.[2] They are dated from c. 47,000 BC. up to c. 44,000 BC.[3] Other known remains of EEMH confidently dated to before 40 ka were found at Riparo Mochi (Italy), Geissenklösterle (Germany), and Isturitz (France).[4][5] Other known remains of EEMH can be dated to before 40 ka with some certainty: those from Grotta del Cavallo in Italy, and from Kents Cavern in England, have been radiocarbon dated to 43±2 ka.[6][7] A number of other early fossils are dated close to or just after 40 ka, including fossils found in Romania (Peștera cu Oase, 39.5±2.5 ka) and Russia (Kostenki-14, 37.5±2.5 ka).[8]

The description as "modern" is used as contrasting with the "archaic" Homo heidelbergensis and Homo neanderthalensis, who lived within Europe during about 400 ka to 37 ka, and who with the arrival of EEMH became extinct or absorbed into their lineage.

The EEMH lineage in the European Mesolithic is also known as "West European Hunter-Gatherer" (WHG). These mesolithic hunter-gatherers emerge after the end of the LGM c. 15 ka and are described as more gracile than the Upper Paleolithic Cro-Magnons.[note 2] The WHG lineage survives in contemporary Europeans, albeit only as a minor contribution overwhelmed by the later Neolithic and Bronze Age migrations.

Chronology

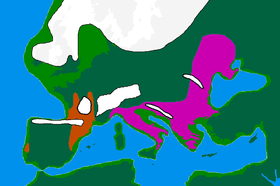

There appear to have been multiple modern human (Homo sapiens) immigration and disappearance events on the European continent, whereupon they interacted with the indigenous Neanderthals (H. neanderthalensis) which had already inhabited Europe for hundreds of thousands of years. In the Middle Palaeolithic, modern humans have been identified 210,000 years ago in Apidima Cave, Greece, and they were replaced by Neanderthals by 170,000 years ago.[10] About 60,000 years ago, marine isotope stage 3 begins, characterised by volatile climatic patterns and sudden retreat and recolonisation events of forestland in way of open steppeland.[11]

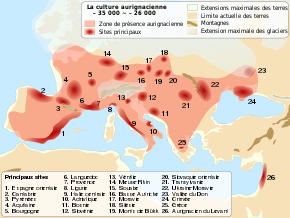

The earliest indication of Upper Palaeolithic modern human immigration into Europe is the Balkan Bohunician industry beginning 48,000 years ago, likely deriving from the Levantine Emiran industry,[12] and the earliest bones in Europe date to roughly 45–43 thousand years ago in Bulgaria,[13] Italy,[14] and Britain.[15] It is unclear, while migrating westward, if they followed the Danube or went along the Mediterranean coast.[5] About 45 to 44 thousand years ago, the Proto-Aurignacian spread out across Europe, probably descending from the Near Eastern Ahmarian culture. After 40,000 years ago with the onset of Heinrich event 4, the Aurignacian proper evolved perhaps in South-Central Europe, and rapidly replaced other cultures across the continent.[16] This wave of modern humans replaced Neanderthal and their Mousterian culture.[17] In the Danube Valley, the Aurignacian features sites far and few between, compared to later traditions, until 35,000 years ago. From here, the "Typical Aurignacian" becomes quite prevalent, and extends until 29,000 years ago.[18]

The Aurignacian was gradually replaced by the Gravettian culture, but it is unclear when the Aurignacian went extinct because it is poorly defined. "Aurignacoid" tools are identified as late as 18 to 15 thousand years ago.[18] It is also unclear where the Gravettian originated from as it diverges strongly from the Aurignician (and therefore may not have descended from it). Hypotheses include evolution: in Central Europe from the Szeletian (which developed from the Bohunician) which existed 41 to 37 thousand years ago; or from the Ahmarian or similar cultures from the Near East or the Caucasus which existed before 40,000 years ago.[19] It is further debated where the earliest occurrence is identified, with the former hypothesis arguing for Germany about 37,500 years ago,[20] and the latter Buran-Kaya III rockshelter in Crimea about 38 to 36 thousand years ago.[21] In either case, the appearance of the Gravettian coincides with a significant temperature drop.[11]

Around 29,000 years ago, marine isotope stage 2 begins and cooling intensifies. This peaked about 21,000 years ago during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) when Scandinavia, the Baltic region, and the British Isles were covered in glaciers, and winter sea ice reached the French seaboard. The Alps were also covered in glaciers, and most of Europe was polar desert, with mammoth steppe and forest steppe dominating the Mediterannean coast.[11] There were two main LGM refugia: the Solutrean in Southwestern Europe, and the Epi-Gravettian in Italy and the Balkans. The glaciers began retreating about 20,000 years ago, and the Magdalenian appears and recolonises Europe over the next couple thousand years.[11] This culture is transitional to the Mesolithic period used by West European Hunter-Gatherers (WHG) starting after 14,000 years ago. At this point in time, the first major warm period since the end of the LGM (the Bølling–Allerød warming) had just begun, and Near Eastern peoples began migrating into and interbreeding with the indigenous Europeans.[22]

Europe was completely re-peopled during the Holocene climatic optimum from 9 to 5 thousand years ago. The WHG contributed significantly to the present-day European genome, alongside Ancient North Eurasians (ANE) which descended from the Siberian Mal'ta–Buret' culture (and split from WHG at the beginning of the LGM). Unlike ANE, the WHG genome is not prevalent on both sides of the Caucasus, and is only seen in any significant measure west of the Caucasus. Most present-day Europeans have a 60–80% WHG/(WHG+ANE) ratio, and the 8,000 year old Mesolithic Loschbour man seems to have had a similar pattern. Near Eastern Neolithic farmers (Early European Farmers, EEF) which split from the European hunter-gatherers about 40,000 years ago started to spread out across Europe starting 8,000 years ago, ushering in the Neolithic. EEF contribute about 30% of ancestry to present-day Baltic populations, and up to 90% in present-day Mediterranean populations. The latter may have inherited WHG ancestry via EEF introgression.[23][24][25] The Eastern Hunter-Gatherers (EHG) population identified around the steppes of the Urals also spread eastward, and the Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherers appear to be a mix of WHG and EHG. Around 4,500 years ago, the immigration of the Yamnaya and Corded Ware cultures from the eastern steppes brought the Bronze Age, the Proto-Indo-European language, and more or less the present-day genetic makeup of Europeans.[26]

Research history

)_(17972406310).jpg)

EEMH have historically been referred to as "Cro-Magnons" in scientific literature until around the 1990s when the term "anatomically modern humans" became more popular.[27] The name "Cro-Magnon" comes from the 5 skeletons discovered by French palaeontologist Louis Lartet in 1868 at the Cro-Magnon rock shelter, Les Eyzies, Dordogne, France, after the area was accidentally discovered while clearing land for a railway station.[28] By this time, fossil skulls dating back tens of thousands of years had been recovered across Europe beginning in 1858 in Western European sites, establishing an archaeological record well predating the biblical chronology.[29]:109 Further excavation around Les Eyzies uncovered stone tools and harpoons, and even more EEMH remains were being found in Western Europe. Because no other early modern human remains were being discovered elsewhere, it was often assumed that this was evidence that humans evolved in Western Europe. By World War II, intensive archaeological efforts had expanded well enough beyond Europe to place humanity's origins in Africa.[30]

In 1735, Carl Linnaeus invented the classification system with his Systema Naturae, classifying humans as a species Homo sapiens. However, in accord with historical race concepts, he created several putative subspecies classifications for different races based on racist behavioural definitions: "H. s. europaeus" (European descent, governed by laws), "H. s. afer" (African descent, impulse), "H. s. asiaticus" (Asian descent, opinions), and "H. s. americanus" (Native American descent, customs).[31] Subsequent racial anthropologists and raciologists began splitting off putative subspecies and sub-races of present-day humans based on unreliable and pseudoscientific metrics gathered from anthropometry, physiognomy, and phrenology in the late 18th century and continuing into the 20th.[29]:93–96 Soon after their discovery, the racial classification system was extended to fossil specimens, including both EEMH and the Neanderthals.[29]:110 In 1869, Louis had proposed the subspecies classification "H. s. fossilis" for the Cro-Magnon remains.[27] Other supposed subraces of the 'Cro-Magnon race' included "H. pre-aethiopicus" for a skull from Dordogne which had "Ethiopic affinities"; "H. predmosti" or "H. predmostensis" for a series of skulls from Brno, Czech Republic, purportedly transitional between Neanderthals and EEMH;[32]:110–111 H. mentonensis for a skull from Menton, France;[32]:88 "H. grimaldensis" for Grimaldi man and other skeletons near Grimaldi, Monaco;[32]:55 and "H. aurignacensis" or "H. a. hauseri" for the Combe-Capelle skull.[32]:15

These 'fossil races', alongside Ernst Haeckel's idea of there being backwards races which require further evolution (social darwinism), popularised the view in European thought that the civilised white man had descended from primitive, low browed ape ancestors through a series of savage races. Prominent brow-ridges were classified as an ape-like trait, and consequently Neanderthals (as well as Aboriginal Australians) were considered a lowly race which were naturally conquered by a superior European race.[29]:116 They were considered to have been the ancestors to specifically living European races.[29]:96 Among the earliest attempts to classify EEMH was done by racial anthropologists Joseph Deniker and William Z. Ripley in 1900, who characterised them as tall and intelligent proto-Aryans superior to other races who descended from Scandinavia and Germany. Further race theories revolved around progressively lighter, blonder, and superior races or subspecies evolving in Central Europe and spreading out in waves to replace their darker ancestors, culminating in the "Nordic race". These aligned well with Nordicism and Pan-Germanism (that is, Aryan supremacy), which gained popularity just before World War I, and was notably used by the Nazis to justify the conquest of Europe and the supremacy of the German people in World War II.[29]:203–205 Stature was among the characteristics used to distinguish these sub-races, so taller EEMH such as the French Cro-Magnon, Paviland, and Grimaldi were classified as ancestral to the "Nordic race", and smaller ones such as Combe-Capelle and Chancelade man (also from France) were considered the forerunners of either the "Mediterranean race" or "Eskimoids".[33] By the 1940s, the positivism movement—which fought to remove political and cultural bias from science and had begun about a century earlier—had gained popular support in European anthropology. Due to this movement and raciology's associations with Nazism, raciology became obsolete.[29]:137

Biology

Physical attributes

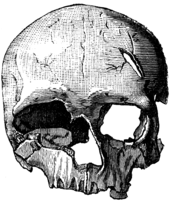

For 28 modern human specimens from 190–25 thousand years ago, average brain volume was estimated to have been about 1,478 cc (90.2 cu in), and for 13 EEMH about 1,514 cc (92.4 cu in). In comparison, present-day humans average 1,350 cc (82 cu in), which is notably smaller. This is because the EEMH brain, though within the variation for present-day humans, exhibits longer average frontal lobe length and taller occipital lobe height. The parietal lobes, however, are shorter in EEMH. It is unclear if this could equate to any functional differences between present-day and early modern humans.[34]

EEMH are physically similar to present-day humans, with a globular braincase, completely flat face, gracile brow ridge, and defined chin. However, the bones of EEMH are somewhat thicker and more robust.[35] Compared to present-day Europeans, EEMH have broader and shorter faces, more prominent brow ridges, bigger teeth, shorter upper jaws, more horizontally oriented cheekbones, and more rectangular eye sockets. The latter three are seen in present-day East Asians.[36]

.jpg)

In early Upper Palaeolithic Western Europe, 20 men and 10 women were estimated to have averaged 176.2 cm (5 ft 9 in) and 162.9 cm (5 ft 4 in), respectively. This is similar to post-industrial modern Northern Europeans. In contrast, in a sample of 21 and 15 late Upper Palaeolithic Western European men and women, the averages were 165.6 cm (5 ft 5 in) and 153.5 cm (5 ft), similar to pre-industrial modern humans. It is unclear why earlier EEMH were taller, especially considering that cold-climate creatures are short-limbed and thus short-statured to better retain body heat. This has variously been explained as: retention of a hypothetically tall ancestral condition; higher quality diet and nutrition due to the hunting of megafauna which later became extinct; functional adaptation to increase stride length and movement efficiency while running during a hunt; increasing territorialism among later EEMH reducing gene flow between communities and increasing inbreeding rate; or statistical bias due to small sample size or because taller people were more likely to achieve higher status in a group and thus were more likely to be buried and preserved.[33]

Their vocal apparatus was like that of present-day humans and they could speak.[37]

It was generally assumed that EEMH, like present-day Europeans, were light skinned as an adaptation to absorb vitamin D from the less luminous sun farther north. However, of the 3 predominant genes responsible for lighter skin in present-day Europeans—KITLG, SLC24A5, and SLC45A2—the latter two, as well as the TYRP1 gene associated with lighter hair and eye colour, experienced positive selection as late as 19 to 11 thousand years ago during the Mesolithic transition. These three became more widespread across the continent in the Bronze Age.[38][39] The variation of the gene which is associated with blue eyes in present-day humans, OCA2, seems to have descended from a common ancestor about 10–6 thousand years ago somewhere in Northern Europe.[40] Such a late timing was potentially caused by overall low population and/or low cross-continental movement required for such an adaptive shift in skin, hair, and eye colouration. However, KITLG experienced positive selection in EEMH (as well as East Asians) beginning approximately 30,000 years ago.[39][41]

Genetics

Genetic evidence suggests early modern humans interbred with Neanderthals. Genes in the present-day genome are estimated to have entered about 65 to 47 thousand years ago, most likely in West Asia soon after modern humans left Africa.[42][43] The approximately 40,000 year old modern human Oase 2 was found, in 2015, to have had 6–9% (point estimate 7.3%) Neanderthal DNA, indicating a Neanderthal ancestor up to four to six generations earlier, but this hybrid Romanian population does not appear to have made a substantial contribution to the genomes of later Europeans. Therefore, it is possible that interbreeding was common between Neanderthals and EEMH which did not contribute to the present-day genome.[44] EEMH which did contribute to the present-day European genome appear to have had descended from a single founder population 37,000 years ago.[22]

While anatomically modern humans (AMH) may have been present in West Asia since before 250,000 years ago,[45] modern non-Africans mainly descend from the main successful out of Africa expansion at around 65–55 ka. This movement was an offshoot of the rapid expansion within East Africa associated with mtDNA haplogroup L3.[46][47] EEMH are associated with mtDNA haplogroup N, also widespread in Central Asia,[48] and with Y-chromosomal haplogroup CF.

Mitochondrial DNA analysis places the early European population as sister group to the East Asian groups of the Upper Palaeolithic, dating the divergence to some 50,000 years ago.[49] EEMH and East Asians did not become reproductively isolated until about 25,000 years ago.[39]

According to Fu et al. (2016), the Mesolithic WHG lineage (dubbed the "Villabruna Cluster") already contains post-LGM admixture from the Near East and Caucasus, ending the period of isolation in EEMH of c. 37 to 14 ka.[note 3]

In terms of unipaternal lineages, EEMH were descended from the patrilineal Y-DNA haplogroups Haplogroup IJ and C1,[note 4][8] and maternal mt-DNA haplogroup N (and descendant haplogroups R and U).[note 5] Y-haplogroup IJ likely arose still in Southwest Asia. Haplogroup I emerged about 35 to 30 ka, either in Europe or West Asia. Y-haplogroup K2a* (K-M2308) is associated with Central Asia, found in Siberian Ust'-Ishim man, but also in the Proto-Aurignacian Oase 1 fossil (Romania). Mt-haplogroup U5 arose in Europe just prior to the LGM, between 35 and 25 ka.

"Bichon man", an Azilian (early Mesolithic) skeleton found in the Swiss Jura, was found to be associated with the WHG lineage. He was a bearer of Y-DNA haplogroup I2a and mtDNA haplogroup U5b1h.[41]

Behaviour and culture

.jpg)

There is a notable technological complexification coinciding with the replacement of Neanderthals with EEMH in the archaeological record, and so the terms "Middle Palaeolithic" and "Upper Palaeolithic" were created to distinguish between these two time periods. Largely based on Western European archaeology, the transition was dubbed the "Upper Palaeolithic Revolution," (extended to be a worldwide phenomenon) and the idea of "behavioural modernity" became associated with this event and early modern cultures. It is largely agreed that the Upper Palaeolithic seems to feature a higher rate of technological and cultural evolution than the Middle Palaeolithic, but it is debated if behavioural modernity was truly an abrupt development or was a slow progression initiating far earlier than the Upper Paleolithic, especially when considering the non-European archaeological record. Behaviourly modern practices include: the production of microliths, the common use of bone and antler, the common use of grinding and pounding tools, high quality evidence of body decoration and figurine production, long distance trade networks, and improved hunting technology.[50][51] In regard to art, the Magdelenian produced some of the most iconic Palaeolithic pieces, and they even elaborately decorated normal, everyday objects.[52]

Manganese and iron oxides were used in rock paintings.

Hunting

It has typically been assumed that EEMH closely studied prey habits in order to maximise return depending on the season. For example, large mammals (including red deer, horses, and ibex) congregate seasonally, and reindeer were possibly seasonally plagued by insects rendering fur sometimes unsuitable for hideworking.[53] There is much evidence that EEMH commonly corralled large prey animals into natural confined spaces (such as against a cliff wall, a cul-de-sac, or a water body) in order to efficiently slaughter whole herds of animals (game drive system). They seem to have scheduled mass kills to coincide with migration patterns, in particular for red deer, horses, reindeer, bison, aurochs, and ibex, and occasionally wooly mammoths.[54] There are also multiple examples of consumption of seasonally abundant fish, becoming more prevalent in the mid-Upper-Palaeolithic.[55] Magdelenian peoples appear to have depended more on small animals, aquatic resources, and plants than predecessors, probably due to the relative scarcity of European big game following the LGM.[11] Nonetheless, some Magdalenian sites have evidence of repeated slaughter of horse and deer herds.[54] In particularly southwestern France, EEMH depended heavily upon reindeer, and so it is hypothesised that these communities followed the herds, with occupation of the Perigord and the Pyrenees only occurring in the summer.[56]

For weapons, EEMH crafted spearpoints using predominantly bone and antler, possibly because these materials were readily abundant. Compared to stone, these materials are compressive, making them fairly shatterproof.[53] These were then hafted onto a shaft to be used as javelins. It is possible that Aurignacian craftsmen further hafted bone barbs onto the spearheads, but firm evidence of such technology is recorded earliest 23,500 years ago, and does not become more common until the Mesolithic.[57] Aurignacian craftsmen produced lozenge-shaped (diamond-like) spearheads. By 30,000 years ago, spearheads were manufactured with a more rounded-off base, and by 28,000 years ago spindle-shaped heads were introduced. During the Gravettian, spearheads with a bevelled base were being produced. By the beginning of the LGM, the spear-thrower was invented in Europe, which can increase the force and accuracy of the projectile.[53] Stone spearheads with leaf- and shouldered-points become more prevalent in the Solutrean. Both large and small spearheads were produced in great quantity, and the smaller ones may have been attached to projectile darts. Archery was possibly invented in the Solutrean, though less ambiguous bow technology is first reported in the Mesolithic. Bone technology was revitalised in the Magdelanian, and long-range technology as well as harpoons become much more prevalent. Some harpoon fragments are speculated to have been leisters or tridents, and true harpoons are commonly found along seasonal salmon migration routes.[54]

At some point in time, EEMH domesticated the dog, probably as a result of a symbiotic hunting relationship. DNA evidence suggests that present-day dogs split from wolves around the beginning of the LGM. However, potential Palaeolithic dogs have been found preceding this—namely the 36,000 year old Goyet dog from Belgium and the 33,000 year old Altai dog from Siberia—which could indicate there were multiple attempts at domesticating European wolves.[58] The 14,500 year old Bonn-Oberkassel dog from Germany was found buried alongside a 40 year old man and a 25 year old woman, as well as traces of red hematite, and is genetically placed as an ancestor to present-day dogs. It was diagnosed with canine distemper virus and probably died between 19–23 weeks of age. It would have required extensive human care to survive without being able to contribute to anything, suggesting that, at this point, humans and dogs were connected by emotional or symbolic ties rather than purely materialistic personal gain.[59]

Housing

EEMH cave sites quite often feature distinct spatial organisation, with certain areas specifically designated for specific activities, such as hearth areas, kitchens, butchering grounds, sleeping grounds, and trash pile. It is difficult to tell if all material from a site was deposited at about the same time, or if the site was used multiple times.[50]

Evidence of constructed dwellings such as tents or huts is quite rare. In Magdalenian Western Europe, stone lined rectangular areas typically 6–15 m2 (65–161 sq ft) were interpreted as having been the foundations or flooring of huts. At Magdelenian Pincevent, France, small, circular dwellings were speculated to have existed based on the spacing of stone tools and bones. These sometimes featured an indoor hearth, work area, or sleeping space (but not all at the same time). A 23,000 year old hut from the Israeli Ohalo II was identified as having used grasses as flooring or possibly bedding, but it is unclear if EEMH also lined their huts with grass or used animal pelts.[60]

Over 70 dwellings constructed by EEMH out of mammoth bones have been identified, primarily from the Russian Plain,[61] possibly semi-permanent hunting camps.[62] These were typically constructed following the LGM after 22,000 years ago, though a hut from Kostenki, Russia, (K11-1a) was dated to 25,000 years ago,[63] and another hut from Moldova, Ukraine, was dated to 44,000 years ago (making it possible it was built by Neanderthals).[64] The bases of the huts were circular, and ranged from 8–24 m2 (86–258 sq ft). Generally multiple huts were built in a locality, placed 1–20 m (3 ft 3 in–65 ft 7 in) apart depending on location. Large bones were used as foundations, tusks for the entrances, and the roofs may have been skins held in place by bones or tusks. Foundation may have extended as far as 40 cm (16 in) underground.[61] Some huts have burned bones, which has typically been interpreted as bones used as fuel for fireplaces due to the scarcity of firewood, and/or disposal of waste. A few huts, however, have evidence of wood burning, or mixed wood/bone burning. K11-1a was a particularly large hut with a diameter of 12.5 m (41 ft) as well as little evidence of occupation and as many as 64 mammoth skulls; because of these, it is speculated to have actually functioned as a food repository rather than a living space.[63]

Portable art

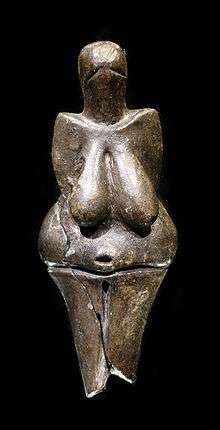

Venus figurines are commonly found associated with EEMH and are the earliest well-acknowledged representation of human figures. These are most commonly found in the Gravettian (notably in the French Upper Périgordian, the Czech Pavlovian, and West Russian Kostenkian) most commonly from 29 to 23 thousand years ago. Almost all Venuses depict naked women, and are generally hand-held sized, and feature a downturned head, no face, thin arms which end at or cross over the breasts, voluminous breasts and buttocks, a prominent abdomen interpreted as pregnancy, tiny and bent legs, and pegged or unnaturally short feet. Venuses vary in proportions, and it is debated if this is due to material choice or if they were intentional design choices.[65] It is suggested that Eastern Europeans Venuses have an emphasis on the breasts and stomach, whereas Western European ones emphasise the hips and thighs.[66]

The earliest interpretations of the Venuses believed these were literal representations of women with obesity or steatopygia (a condition where a woman's body stores more fat in the thighs and buttocks, making them especially prominent); or that EEMH believed depictions of things had magical properties over the subject, and that such a depiction of a pregnant woman would facilitate fertility and fecundity. In 1938, French historian Luce Passemard observed that steatopygia is rarely depicted, and enlarged breasts and buttocks were likely symbolic. This led to hypotheses that ideal womanhood for EEMH involved obesity, or that the Venuses were used by men as erotica due to the exaggeration of body parts typically sexualised in Western Culture and the lack of detail to individualising traits such as the face and limbs. However, extending present-day Western norms to EEMH is contested. In the late 20th century, American archaeologist Alexander Marshack suggested that they represent the sex role of women in EEMH society as well as female physical processes such as puberty, menstruation, sexual intercourse, pregnancy, giving birth, and lactation. Somewhat similar female iconography is found in Neolithic settlements representing mother goddesses, but it is unclear if this can be extended to Palaeolithic Venuses.[65]

Depictions of males are rare and contested in the Gravettian, the only reliable one being a fragmented ivory figurine from the grave of a Pavlovian site in Brno, Czech Republic (it is also the only statuette found in a Palaeolithic grave). In contrast, 2-D Magdalenian engravings from 15 to 11 thousand years ago often depict males, indicated by an erect penis and facial hair, though profiles of women with an exaggerated buttock are much more common.[65] Still, there are less than 100 depictions of males. Of them, about a third are depicted with erections.[67]

Phallic-like batons were also carved out of horn, bone, or stone (all with erections), most commonly through the Solutrean and Magdalenian, and several are depicted as circumcised and seemingly bearing some ornamentation such as piercings, scarification, or tattooing. About 60 batons have been hypothesised to be phallic. The purpose of these batons has been debated, which suggestions for spiritual or religious purposes, ornamentation or status symbol, currency, drumsticks, dildos, tent holders, weaving tools, or spear throwers. Some smaller phallic batons, 30 (11.8 in) to a few centimetres long, were produced in some locales, and these were quite early on interpreted as sexual toys.[67]

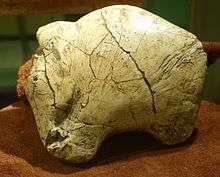

Depictions of animals were commonly produced by EEMH. As of 2015, as many as 50 Aurignacian ivory figurines and fragments have been recovered from the German Swabian Jura. Of the discernible figures, most represents mammoths and lions, and a few horses, bison, possibly a rhino, waterfowl, fish, and small mammals. These sculptures are hand-sized and would have portable works, and some figurines were made into wearable pendants. Some figurines also featured enigmatic engravings, dots, marks, lines, hooks, and criss-cross patterns.[68]

EEMH also made purely symbolic engravings. There are several plaques of bone or antler (referred to as polishers, spatulas, palettes, or knives) which feature series of equidistantly placed notches, most notably the well-preserved 32,000 year old Blanchard plaque from L'Abri Blanchard, France, which features 24 markings in a seemingly serpentine pattern. These have been speculated to have been an early counting system for tallying items such as animals killed, or some other notation system. Marshack postulated they may be calendars.[69]

Body art

EEMH are commonly associated with large pieces of pigments ("crayons"), namely made of red ochre. For EEMH, it is typically assumed that ochre was used for some symbolic purposes, most notably for cosmetics such as body paint. This is because ochre in some sites had to be imported from incredibly long distances, and it is also associated with burials. It is unclear why they specifically chose red ochre instead of other colours. In terms of colour psychology, popular hypotheses include the putative "female cosmetic coalitions" hypothesis and the "red dress effect". It is also possible that ochre was chosen for its utility, such as an ingredient for adhesives, hide tanning agent, insect repellent, sunscreen, medicinal properties, dietary supplement, or as a soft hammer.[70] EEMH appear to have been using grinding and crushing tools to process ochre before applying it to the skin.[52]

In 1962, French archaeologists Saint-Just and Marthe Péquart identified bi-pointed needles in the Magdelenian Le Mas-d'Azil, which they speculated might have been used in tattooing.[52] Hypothesised depictions of penises from most commonly the Magdalenian (though a few dating back to the Aurignacian) appear to be decorated with tattoos, scarification, and piercings.[67]

Wearable art

EEMH produced beads, which are typically assumed to have been attached to clothing or portable items as body decoration. Beads had already been in use since the Middle Palaeolithic, but production dramatically increased in the Upper Palaeolithic. It is unclear why communities chose specific raw materials over other ones, and they seem to have upheld local bead making traditions for a very long time.[71] For example, Mediterranean communities used specific types of marine shells to make beads and pendants for more than 20,000 years; and Central and Western European communities often used pierced animal (and less commonly human) teeth.[72] In the Aurignacian, beads and pendants were being made of shells, teeth, ivory, stone, bone, and antler; and there are a few examples of use of fossil materials including a belemnite, nummulite, ammonite, and amber. They may have also been producing ivory and stone rings, diadems, and labrets. Beads could be manufactured in numerous different styles, such as conical, elliptical, drop-shaped, disc-shaped, ovoid, rectangular, trapezoidal, and so on.[71] Beads may have been used to facilitate social communication, to display the wearer's socio-economic status, as they could have been capable of communicating labour costs (and thereby, a person's wealth, energy, connections, etc.) simply by looking at them.[72]

The Dolní Věstonice I and III and Pavlov I sites in Moravia, Czech Republic, yielded many clay fragments (dating to 32 to 29 thousand years ago) with textile impressions. These indicate a highly sophisticated and standardised textile industry, including the production of: single-ply, double-ply, triple-ply, and braided string and cordage; knotted nets; wicker baskets; and woven cloth including simple and diagonal twined cloth, plain woven cloth, and twilled cloth. Some cloths appear to have a design pattern. There are also plaited items which may have been baskets or mats. Due to the wide range of textile gauges and weaves, it is possible they could also produce wall hangings, blankets, bags, shawls, shirts, skirts, and sashes. These people used plant rather than animal fibres,[66] probably nettle.[73] Such plant fibre fragments have also been recorded in France, Germany, and Eastern Europe during and following the Gravettian, indicating the technology was widespread and well in use.[66] The inhabitants of Dzudzuana Cave, Georgia, appear to have been staining flax fibres with plant-based dyes, including yellow, red, pink, blue, turquoise, violet, black, brown, gray, green, and khaki.[73] The emergence of textiles in the European archaeological record also coincides with the proliferation of the sewing needle in European sites. Ivory needles are found in most late Upper Palaeolithic sites, which could correlate to frequent sewing, and the predominance of small needles (too small to tailor clothes out of hide and leather) could indicate work on softer woven fabrics or accessory stitching and embroidery of leather products.[66]

There is some potential evidence of simple loom technology. However, these have also been interpreted as either hunting implements or art pieces. A bone rod from Předmostí, Czech Republic, may have been a net spacer or a spearhead. Rounded objects made of mammoth phalanges from Předmostí and Avdeevo, Russia, may have been loom weights or human figures. Perforated, washer-like ivory or bone discs from Sungir, Russia, and Mezhyrich, Ukraine, were potentially spindle whorls. A foot-shaped piece of ivory from Kniegrotte, Germany, was possibly a comb or a decorative pendant.[66]

Some Venuses depict hairdos and clothing worn by Gravettian women. The Venus of Willendorf seems to be wearing a cap, possibly woven fabric or made from shells, featuring at least seven rows and an additional two half-rows covering the nape of the neck. It may have been made starting at a knotted centre and spiraling downward from right to left, and then backstitching all the rows to each other. The Kostenki-1 Venus seems to be wearing a similar cap, though each row seems to overlap the other. The Venus of Brassempouy seems to be wearing some nondescript open, twined hair cover. The engraved Venus of Laussel from France seems to be wearing some headwear with rectangular gridding, and could potentially represent a snood. Most East European Venuses with headwear also display notching and checkwork on the upper body which are suggestive of bandeaux (a strip of cloth bordering around the tops of the breasts) with some even featuring straps connecting it to around the neck; these seem to be absent in Western European Venuses. Some also wear belts: in Eastern Europe, these are seen on the waist; whereas in Central and Western Europe they are worn on the low hip. The Venus of Lespugue seems to be wearing a plant fibre string skirt comprising 11 cords running behind the legs.[66]

Music

EEMH are known to have created flutes out of hollow bird bones as well as mammoth ivory, first appearing in the archaeological record with the Aurignacian about 40,000 years ago in the German Swabian Jura. The Swabian Jura flutes appear to have been able to produce a wide range of tones. One virtually complete flute made of the radius of a griffon vulture from Hohle Fels measures 21.8 cm (8.6 in) in length and 0.8 cm (0.31 in) in diameter. The bone had been smoothed down and was pierced with holes. These finger holes exhibit cut marks, which could indicate the exact placement of these holes was specifically measured to create concert pitch (that is, to make the instrument in tune) or a scale. The part near the elbow joint had two V-shaped carvings, presumably a mouthpiece. Ivory flutes would have required a great time investment to make, as it requires more skill and precision to craft compared to a bird bone flute. A section of ivory must be sawed off to the correct size, cut in half so it can be hollowed out, and then the two pieces have to be refitted and stuck together by an adhesive in an air-tight seal.[74]

Such sophisticated music technology could potentially speak to a much longer musical tradition than the archaeological record indicates, as modern hunter-gatherers have been documented to create instruments out of: more biodegradable materials (less likely to fossilise) such as reeds, gourds, skins, and bark; more or less unmodified items such as horns, conch shells, logs, and stones; and their weapons, including spear thrower shafts or boomerangs as clapsticks, or a hunting bow. It is speculated that a few EEMH artefacts represent whistles, bullroarers, or percussion instruments such as rasps, but these are hard to prove.[74]

Language

It is unclear what early languages would have sounded like because, though EEMH languages likely contributed to present-day languages, words denature and are replaced by entirely original words quite rapidly, making it difficult to identity language cognates (a word in multiple different languages which descended from a common ancestor) which originated before 9 to 5 thousand years ago. Nonetheless, it has been controversially hypothesised that Eurasian languages are all related and form the Nostratic languages with an early common ancestor existing just after the end of the LGM. In 2013, evolutionary biologist Mark Pagel and colleagues postulated that among Nostratic languages, frequently used words more often have speculated cognates, and that this was evidence that 23 identified words were "ultraconserved" and supposedly changed very little in use and pronunciation, descending from a common ancestor about 15,000 years ago at the end of the LGM.[75] Archaeologist Paul Heggarty said that Pagel's data was subjective interpretation of supposed cognates, and the extreme volatility of sound and pronunciation of words (for example, Latin [akwam] "water" → French [o] in just 2,000 years) makes it unclear if cognates can even be identified that far back if they do indeed exist.[76]

Religion and rituals

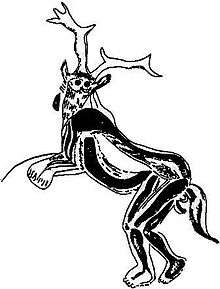

There are a few examples of depictions of human-animal chimaeras which are generally interpeted as the centre of some shamanistic ritual.[77] Historically, these have been argued to represent some cultural revolution and the origins of subjectivity.[78]

- The Aurignacian Hohlenstein-Stadel, Swabian Jura, has yielded the famous lion-human sculpture. It is 30 cm (12 in) tall, which is much larger than the other Swabian Jura figurines. A possible second lion-human was also found in the nearby Hohle Fels. An ivory slab from Geissenklösterle has a carved relief of a human figure with its arms raised in the air wearing a hide, the "worshipper".[68]

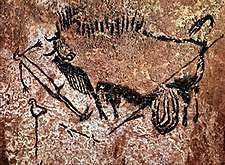

- The 22 to 17 thousand year old Grotte de Lascaux, France, has a bird-human hybrid between a rhino and a butchered bison, with a bird on top of a pole placed near the figure's right hand. A bird on a stick is used as a symbol of mystical power by some modern shamanistic cultures who believe that birds are psychopomps, and can move between the land of the living and the land of the dead. In these cultures, they believe the shaman can either transform into a bird or use a bird as a spirit guide.[77]

- A 14,000 year old large stone from Cueva del Juyo, Spain, seems to have been carved to be the conjoined face of a man on the right and a big cat on the left (when facing it). The man half seems to feature a mustache and a beard. The cat half (either a leopard or a lion) has slanting eyes, a snout, a fang, and spots on the muzzle suggestive of whiskers.[77]

- The 13,000 year old paintings of the Grotte des Trois-Frères, France, feature a web-footed reindeer, a bear with a wolf head and another with a bison tail, and a human-reindeer chimaera (the "Sorcerer"). The "Sorcerer" appears to be herding animals and playing a musical bow, and fully dressed with a stag head as well as a pelt extending to the figure's legs. It is placed about 3.7 m (12 ft) off the floor and is possibly made to be looking out over all the animal figures in the cave.[77]

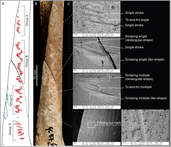

The earliest evidence of skull cups, and thus ritual cannibalism, comes from the Magdalenian of Gough’s Cave, England. Further concrete evidence of such rituals does not appear until after the Palaeolithic. The Gough's Cave cup seems to have followed a similar method of scalping as those from Neolithic Europe, with incisions being made along the midline of the skull (whereas the Native American method of scalping involved a circular incision around the crown). Earlier examples of non-ritual cannibalism in Europe do not seem to have followed the same method of defleshing.[79] In addition, Gough’s Cave also yielded a human radius with a zig-zag engraving. Compared to other artefacts in the cave or common to the Magdalenian period, the radius was modified quite little, with the engraving probably quickly etched on (indicated by scrape marks not recorded on any other Magdalenian engraving), and the bone broken and discarded soon thereafter. This may indicate the bone's only function was as a tool in some cannibalistic and/or funerary ritual, rather than being prepared to be carried around by the group as an ornament or tool.[80]

Spanish archaeologists Leslie G. Freeman and Joaquín González Echegaray argued that Cueva del Juyo was specifically modified to serve as a sanctuary site to carry out rituals. They said the inhabitants dug out a triangular trench and filled it with offerings including Patella (limpets), the common periwinkle (a sea snail), pigments, the legs and jaws (possibly with meat still on them) of red and roe deer, and a red deer antler positioned upright. The trench and offerings were then filled in with dirt, and a seemingly flower-like arrangement of bright cylindrical pieces of red, yellow, and green pigments was placed on top. This was then buried with clay, stone slabs, and bone spearpoints. The clay shell was covered by a 900 kg (2,000 lb) slab of limestone supported by large flat stones. Somewhat similar structures associated with some representation of a human have also been found elsewhere in Magdalenian Spain, such as at Cueva Erralla, Entrefoces rock shelter, Cueva de Praileaitz, Cueva de la Garma, and Cueva de Erberua.[81]

Funerals

EEMH commonly buried their dead with a variety symbolic grave goods as well as red ochre, and multiple people were often buried in the same grave. Across Europe, burials with multiple individuals most often feature both sexes. The most lavish of these graves is a grave from Sungir, Russia, where a boy and a girl were placed crown-to-crown in a long, shallow grave, and adorned with thousands of perforated ivory beads, hundreds of perforated arctic fox canines, ivory pins, disc pendants, ivory animal figurines, and mammoth tusk spears. The beads were a third the size of those found with a man from the same site, which could indicate these small beads were specifically designed for the children.[82] Only two other Upper Palaeolithic graves were found with grave goods other than personal adornment (one from Arene Candide, Italy, and Brno, Cezch Republic), and the grave of these two children is unique in bearing any functional implements (the spears) as well as a bone from another individual (a partial femur). The 5 other buried individuals from Sungir did not receive nearly as many grave goods, with one seemingly given no formal treatment whatsoever.[83]

Due to such rich material culture and the marked difference of treatment between different individuals, it has been suggested that these peoples had a complex society beyond band level, and with social class distinction. In this model, young individuals given elaborate funerals were potentially born into a position of high status. Because of the great amount of time, labour, and resources all these grave goods would have required, it has been hypothesised that the grave goods were made long in advance of the ceremony. Because of such planning for multiple burials as well as their abundance in the archaeological record, the seemingly purposeful presence of both sexes, and an apparent preference for individuals with some congenital disorder[82] (about a third of identified burials[83]), it is speculated that these cultures practiced human sacrifice.[82][83]

Assemblages and fossils

| Site | Region (country) | Industry | Age (ka) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grotta del Cavallo | Italy | Uluzzian (Proto-Aurignacian) | 44 | In November 2011, tests conducted at the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit in England on what were previously thought to be Neanderthal baby teeth, which had been unearthed in 1964 from the Grotta del Cavallo in Italy. These were identified as the oldest anatomically modern remains ever discovered in Europe, dating from between 43,000 and 45,000 years ago. No tools were associated with the find. |

| Geissenklösterle | Central Europe (Germany) | Proto-Aurignacian | 42 | The bone flute of Geissenklösterle (Swabia) has been radiocarbon dated to 43–42 ka. The so-called adorant from the Geißenklösterle cave is somewhat younger (40–35 ka). Other paleolithic art of the early Aurignacian was found in the Swabian Alb area, including Venus of Hohle Fels and the Lion-man figurine (see Caves and Ice Age Art in the Swabian Jura)[84] No dated human remains are associated with these finds. |

| Kostenki-14 | Eastern Europe (Russia) | Proto-Aurignacian | 38 | A male from Kostenki-14 (Markina Gora), dated 35–40 ka, was found to have close ancestry with both "Mal'ta boy" (24 ka) of central Siberia (Ancient North Eurasian) and to the later Mesolithic hunter-gatherers of Europe and western Siberia, as well as with a basal population ancestral to Early European Farmers.[8] |

| Peștera cu Oase | Southeastern Europe (Romania) | Proto-Aurignacian | 38 |  Oase 2 skull Peștera cu Oase ("Bones Cave") near the Iron Gates in Romania appears to be a cave bear den; the human remains may have been prey or carrion. No tools are associated with the finds. Oase 1 holotype is a robust mandible which combines a variety of archaic, derived early modern, and possibly Neanderthal features. The modern attributes place it close to EEMH among Late Pleistocene samples. The fossil is one of the few finds in Europe which could be directly dated and is at least 37,800 years old. Oase 2 (and fragments Oase 3), discovered in 2005, is the skull of a young male, again with mosaic features, some of which are paralleled in the Oase 1 mandible.[85] |

| Kents Cavern | Western Europe (UK) | Proto-Aurignacian | 36 | The Kents Cavern find is a prehistoric maxilla (upper jawbone) fragment was uncovered in the cavern during a 1927 excavation in Kents Cavern by the Torquay Natural History Society, and named Kents Cavern 4. In 1989 the fossil was radiocarbon dated to be from 36,400–34,700 years ago, although various fauna fossils in older strata present on the site have been dated in 2011 to 44,200–41,500 years ago and indirectly associated with the human remains, the latest datings and conclusions in question being highly disputed.[7] |

| Sungir | Eastern Europe (Russia) | Aurignacian | 34 |  Reconstruction from Sungir 2 DNA analysis at c. 34,000 BP. Additional pollen finds suggest the relative warm spell of the "Greenland interstadial (GI) 5" (two hundred kilometres east of Moscow, on the outskirts of Vladimir, near the Klyazma River). mtDNA analysis shows that the four individuals tested from Sungir belong to mtDNA haplogroup U. The individual from Burial 1 belongs to mtDNA haplogroup U8c, while the three individuals from Burial 2 belong to mtDNA haplogroup U2. Y-DNA analysis shows that all four of the tested individuals from Sungir belong to Y-DNA haplogroup C1a2.[86] |

| Kostenki-12 | Eastern Europe (Russia) | Aurignacian | 33 | Dated at 32,600 ± 1,100 radio-carbon years, the find from Kostenki consists of a tibia and a fibula in a rich culture layer. The occupation layers contain bone and ivory artifacts, including possible figurative art, and fossil shells imported more than 500 kilometers.[87][88] |

| Gower | Western Europe (UK) | Aurignacian | 33 | Despite its name, the Red Lady of Paviland is a partial skeleton of a young male, lacking a skull. It was discovered in 1823 in a cave burial in Gower, South Wales, United Kingdom. The bones were stained with ochre, and it was the first human fossil to have been found anywhere in the world. At 33,000 years old, it is still the oldest ceremonial burial of a modern human ever discovered anywhere in Western Europe.[89] Associated finds were red ochre anointing, a mammoth skull, and personal decorations suggesting shamanism or other religious practice. Grave goods are considered late Aurignacian or Early Gravettian in appearance. Genetic analysis of mtDNA yielded the haplogroup H, the most common group in Europe.[90] |

| La Quina Aval | Western Europe (France) | Aurignacian | 33 | Consisting of a partial juvenile mandible, the find is also associated with early Aurignacian tools. The jaw has some archaic features, though it is mainly modern.[91] The find is dated to max 33,000–32,000 radiocarbon years.[87] |

| Les Roisà Mouthiers | Western Europe (France) | Aurignacian | 32 | There are diagnostic modern human remains associated with a later Aurignacian assemblage at Les Roisà Mouthiers, France. The date is likely not older than 32,000 radiocarbon years.[87] |

| Mladeč caves | Central Europe (Czech Republic) | Aurignacian | 31 | The Mladeč caves in Moravia have yielded the remains of several individuals, but few artifacts. The artifacts found have tentatively been classified as Aurignacian. The finds have been radiocarbon dated to around 31,000 radiocarbon years (somewhat older in calendar years),[92] Mladeč 2 is dated to 31,320 +410, -390, Mladeč 9a to 31,500 +420, -400 and Mladeč 8 to 30,680 +380, -360 14C years.[87] |

| Peștera Muierilor | Southeastern Europe (Romania) | Aurignacian | 31 |

The Peștera Muierilor ("Women's Cave") find is a single, fairly complete cranium of a woman with rugged facial traits and otherwise modern skull features, found in a lower gallery of the cave, among numerous cave bear remains. Radiocarbon dating yielded an age of 30,150 ± 800 years. No associated tools were found.[87] |

| Muierii and Cioclovina Caves | Southeastern Europe (Romania) | Aurignacian | 30 | Cioclovina 1 is a complete neurocranium from a robust individual lacking all facial bones. The find is from a cave bear den, Cioclovina Cave, Romania. It is dated at 29,000 ± 700 radiocarbon years.[87][93] |

| Cro-Magnon | Western Europe (France) | Aurignacian | 29 |  Cro-Magnon 2, the female skull found at Cro-Magnon (1884 drawing) Compared to Neanderthals, the skeletons showed the same high forehead, upright posture and slender (gracile) skeleton as modern humans. The other specimens from the site are a female, Cro-Magnon 2, and another male, Cro-Magnon 3. The condition and placement of the remains of Cro-Magnon 1, along with pieces of shell and animal teeth in what appear to have been pendants or necklaces, raises the question of whether they were buried intentionally. If Cro-Magnons buried their dead intentionally, it suggests they had a knowledge of ritual, by burying their dead with necklaces and tools, or an idea of disease and that the bodies needed to be contained.[94] Analysis of the pathology of the skeletons shows that the humans of this period led a physically difficult life. In addition to infection, several of the individuals found at the shelter had fused vertebrae in their necks, indicating traumatic injury; the adult female found at the shelter had survived for some time with a skull fracture. As these injuries would be life-threatening even today, this suggests that Cro-Magnons relied on community support and took care of each other's injuries.[94] The Abri of Cro-Magnon is part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site of the "Prehistoric Sites and Decorated Caves of the Vézère Valley".[95] |

| Předmostí | Central Europe (Czech Republic) | Aurignacian-Gravettian | 26 | The Předmostí site, near Přerov, Moravia, was discovered in the late 19th century. Excavations were conducted between 1884 and 1930. As the original material was lost during World War II, in the 1990s, new excavations were conducted.[96] The Předmostí site appears to have been a living area with associated burial ground with some 20 burials, including 15 complete human interments, and portions of five others, representing either disturbed or secondary burials. Cannibalism has been suggested to explain the apparent subsequent disturbance,[97] though it is not widely accepted. The non-human fossils are mostly mammoth. Many of the bones are heavily charred, indicating they were cooked. Other remains include fox, reindeer, ice-age horse, wolf, bear, wolverine, and hare. Remains of three dogs were also found, one of which had a mammoth bone in its mouth.[98] The Předmostí site is dated to between 24,000 and 27,000 years old. The people were essentially similar to the French Cro-Magnon finds. Though undoubtedly modern, they had robust features indicative of a big-game hunter lifestyle. They also share square eye socket openings found in the French material.[99] |

| Balzi Rossi | Italy | Aurignacian-Gravettian | 25 | Grimaldi Man is a find from the Ligurian Coast in Italy. The caves yielded several finds, among them two fairly complete skeletons in the lower Aurignacian layer. Though the age and accompanying tools suggests Cro-Magnon, the skeletons differ physically from the large and robust Cro-Magnons, being slender and rather short.[100] The remains from one of the caves, the "Barma Grande", have in recent times been radiocarbon dated to 25 ka.[101] The Venus figurines of Balzi Rossi have been dated to the later Gravettian or Epi-Gravettian, 24 to 19 ka.[102] |

| Abrigo do Lagar Velho | Western Europe (Portugal) | Gravettian | 24 | The Lapedo child from Abrigo do Lagar Velho, Portugal, about 24,000 years old, a fairly complete and quite robust skeleton, possibly showing some Neanderthal traits.[103] |

| Abri Pataud | Western Europe (France) | Solutrean | 21 |

The Abri Pataud shelter shows human habitation throughout the Aurignacian to Solutrean, but was abandoned in the early Magdalenian, about 17 ka. "Pataud woman" is the name given to the remains of a young woman, about 20 years old, deposited with the body of a newborn child, and is about 21,000 years old. The woman's skull was buried separately, about four meters from the body, lying protected between stones. |

| Chancelade | Western Europe (France) | Magdalenian | 15 |  The Chancalade skull Chancelade man, a short and stocky older man buried in Chancelade, France, was found with Magdalenian tools.[104] Several other more fragmentary finds, like the skeleton from Laugerie-Basse and the Duruthy cave near Sorde-l'Abbaye, have traditionally been linked to the Chancelade man.[105] The morphological difference in the Chancelade skull compared to the "stockier" Cro-Magnon type has been taken as evidence for a Gravettian or Magdalenian-era influx of a different population unrelated to the Aurignacian EEMH. |

| Cap Blanc rock shelter | Western Europe (France) | Magdalenian-Azilian | 14 | Magdalenian Girl is a female skeleton, discovered in Dordogne in 1911. Dating to the later Magdalenian, transitional to the beginning Mesolithic. |

| Grotte du Bichon | Western Europe (Switzerland) | Magdalenian-Azilian | 14 | Bichon man is the skeleton of a young male of the mesolithic hunter-gatherer (WHG) lineage. |

| Ripari Villabruna | Italy | Magdalenian-Azilian | 14 |

Villabruna 1 is a skeleton, dated 14.1–13.8 ka, buried in a shallow pit, the head turned to the left with arms stretched touching the body, with grave goods typical of hunter-gatherer equipment. Villabruna 1 is the oldest bearer of Y-haplogroup R1b (R1b1a-L754* (xL389,V88)) found in Europe, and has been taken as a representative of the beginning post-LGM (Mesolithic) migration movement from the Near East.[22] |

In popular culture

The "caveman" archetype is quite popular in both literature and visual media and can be portrayed as highly muscular, hairy, or monstrous, and to represent a wild and animalistic character. Cavemen first appeared in visual media in D. W. Griffith's 1912 Man's Genesis, and among the first appearances in fictional literature were Stanley Waterloo's 1897 The Story of Ab and Jack London's 1907 Before Adam.[106] Cavemen have also been popularly potrayed (inaccurately) as confronting dinosaurs, first done in Griffith's 1914 Brute Force (the sequel to Man's Genesis) featuring a Ceratosaurus.[107] EEMH are also portrayed interacting with Neanderthals, such as in H. G. Wells' 1927 The Grisly Folk, William Golding's 1955 The Inheritors, Björn Kurtén's 1978 Dance of the Tiger, Jean M. Auel's 1980 Clan of the Cave Bear and her Earth's Children series, and Elizabeth Marshall Thomas' 1987 Reindeer Moon and its 1990 sequel The Animal Wife. EEMH are generally portrayed as superior in some way to Neanderthals which allowed them to take Europe.[108]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to European early modern humans. |

- Anatomically modern humans

- Peopling of Eurasia

- Neanderthal extinction – Extinction of Neanderthals around 40,000 years ago

- Ancient North Eurasian – Archaeogenetic name for an ancestral genetic component

- Genetic history of Europe

- Azilian

Notes

- "The term 'Cro-Magnon' has no formal taxonomic status, since it refers neither to a species or subspecies nor to an archaeological phase or culture. The name is not commonly encountered in modern professional literature in English, since authors prefer to talk more generally of anatomically modern humans (AMH). They thus avoid a certain ambiguity in the label 'Cro-Magnon', which is sometimes used to refer to all early moderns in Europe (as opposed to the preceding Neanderthals), and sometimes to refer to a specific human group that can be distinguished from other Upper Paleolithic humans in the region. Nevertheless, the term 'Cro-Magnon' is still very commonly used in popular texts because it makes an obvious distinction with the Neanderthals, and also refers directly to people rather than to the complicated succession of archaeological phases that make up the Upper Paleolithic. This evident practical value has prevented archaeologists and human paleontologists from dispensing entirely with the idea of Cro-Magnons."[1]

- The process leading to the development of smaller and more fine-boned humans seems to have begun at least 50,000–30,000 years ago.[9]

- "beginning with the Villabruna Cluster at least ~14,000 years ago, all European individuals analysed show an affinity to the Near East. This correlates in time to the Bølling-Allerød interstadial, the first significant warming period after the Glacial Maximum. Archaeologically, it correlates with cultural transitions within the Epigravettian in southern Europe and the Magdalenian-to-Azilian transition in western Europe. Thus, the appearance of the Villabruna Cluster may reflect migrations or population shifts within Europe at the end of the Ice Age, an observation that is also consistent with the evidence of mitochondrial DNA turnover".[22]

- Kostenki-14 (Russia): C1b, Goyet Q116-1 (Belgium) C1a.[22]

- Haplogroup N was found in two Gravettian-era fossils, Paglicci 52 Paglicci 12[48]

References

- Fagan, B. M. (1996). The Oxford Companion to Archaeology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507618-9.

- Hublin, J.; Sirakov, N.; Aldeias, V.; et al. (2020). "Initial Upper Palaeolithic Homo sapiens from Bacho Kiro Cave, Bulgaria". Nature (581): 299–302. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2259-z.

- Fewlass, H.; Talamo, S.; Wacker, L.; et al. (2020). "A 14C chronology for the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic transition at Bacho Kiro Cave, Bulgaria". Nature Ecology and Evolution (4): 794–801. doi:10.1038/s41559-020-1136-3.

- Fu, Qiaomei; et al. (23 October 2014). "The genome sequence of a 45,000-year-old modern human from western Siberia". Nature. 514 (7523): 445–49. Bibcode:2014Natur.514..445F. doi:10.1038/nature13810. hdl:10550/42071. PMC 4753769. PMID 25341783.

- 42.7–41.5 ka (1σ CI). Douka, Katerina; Grimaldi, Stefano; Boschian, Giovanni; Angiolo; Higham, Thomas F. G. (2012). "A new chronostratigraphic framework for the Upper Palaeolithic of Riparo Mochi (Italy)". Journal of Human Evolution. 62: 286–299. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.11.009..

- Benazzi, S.; Douka, K.; Fornai, C.; Bauer, C. C.; Kullmer, O.; Svoboda, J. Í.; Pap, I.; Mallegni, F.; Bayle, P.; Coquerelle, M.; Condemi, S.; Ronchitelli, A.; Harvati, K.; Weber, G. W. (2011). "Early dispersal of modern humans in Europe and implications for Neanderthal behaviour". Nature. 479 (7374): 525–28. Bibcode:2011Natur.479..525B. doi:10.1038/nature10617. PMID 22048311.

- Higham, Tom; Compton, Tim; Stringer, Chris; Jacobi, Roger; Shapiro, Beth; Trinkaus, Eric; Chandler, Barry; Gröning, Flora; Collins, Chris; Hillson, Simon; O'Higgins, Paul; FitzGerald, Charles; Fagan, Michael (24 November 2011). "The earliest evidence for anatomically modern humans in northwestern Europe". Nature. 479 (7374): 521–524. Bibcode:2011Natur.479..521H. doi:10.1038/nature10484. PMID 22048314. Lay summary – BBC News (2011-11-02).

- Seguin-Orlando, A.; Korneliussen, T. S.; Sikora, M.; Malaspinas, A.-S.; Manica, A.; Moltke, I.; Albrechtsen, A.; Ko, A.; Margaryan, A.; Moiseyev, V.; Goebel, T.; Westaway, M.; Lambert, D.; Khartanovich, V.; Wall, J. D.; Nigst, P. R.; Foley, R. A.; Lahr, M. M.; Nielsen, R.; Orlando, L.; Willerslev, E. (6 November 2014). "Genomic structure in Europeans dating back at least 36,200 years". Science. 346 (6213): 1113–1118. Bibcode:2014Sci...346.1113S. doi:10.1126/science.aaa0114. PMID 25378462.

- Hawks, J.; Wang, E. T.; Cochran, G. M.; Harpending, H. C.; Moyzis, R. K. (2007). "Recent acceleration of human adaptive evolution". PNAS. 104 (52): 20753–20758. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10420753H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0707650104. PMC 2410101. PMID 18087044.

- Harvati, K.; et al. (2019). "Apidima Cave fossils provide earliest evidence of Homo sapiens in Eurasia". Nature. 571 (7766): 500–504. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1376-z. PMID 31292546.

- El Zaatari, S.; Hublin, J.-J. (2014). "Diet of upper paleolithic modern humans: Evidence from microwear texture analysis". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 153 (4): 570–581. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22457.

- Hoffecker, J. F. (2009). "The spread of modern humans in Europe". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (38): 16040–16045. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10616040H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903446106. PMC 2752585. PMID 19571003.

- Hublin, J.-J.; Sirakov, N.; et al. (2020). "Initial Upper Palaeolithic Homo sapiens from Bacho Kiro Cave, Bulgaria". Nature. 581 (7808): 299–302. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2259-z. PMID 32433609.

- Benazzi, S.; Douka, K.; Fornai, C.; Bauer, C.C.; Kullmer, O.; Svoboda, J.Í.; Pap, I.; Mallegni, F.; Bayle, P.; Coquerelle, M.; Condemi, S.; Ronchitelli, A.; Harvati, K.; Weber, G.W. (2011). "Early dispersal of modern humans in Europe and implications for Neanderthal behaviour". Nature. 479 (7374): 525–528. Bibcode:2011Natur.479..525B. doi:10.1038/nature10617. PMID 22048311.

- Higham, T.; Compton, T.; Stringer, C.; Jacobi, R.; Shapiro, B.; Trinkaus, E.; Chandler, B.; Gröning, F.; Collins, C.; Hillson, S.; o’Higgins, P.; Fitzgerald, C.; Fagan, M. (2011). "The earliest evidence for anatomically modern humans in northwestern Europe". Nature. 479 (7374): 521–524. Bibcode:2011Natur.479..521H. doi:10.1038/nature10484. PMID 22048314.

- Hoffecker, J. F. (1 July 2009). "The spread of modern humans in Europe". PNAS. 106 (38): 16040–16045. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10616040H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903446106. PMC 2752585. PMID 19571003.

- Higham, T.; Douka, K.; Wood, R.; et al. (2014). "The timing and spatiotemporal patterning of Neanderthal disappearance". Nature. 512 (7514): 306–309. Bibcode:2014Natur.512..306H. doi:10.1038/nature13621. hdl:1885/75138. PMID 25143113.

- Henry-Gambier, D. (2002). "The Cro-Magnon Human Remains (Les Eyzies-de-Tayac, Dordogne): New information on their chronological position and cultural attribution". Bulletins et mémoires de la Sociétéd’Anthropologie de Paris. 14 (1–2).

- Svoboda, J. (2007). "The Gravettian on the Middle Danube". Paleo: 204. doi:10.4000/paleo.607.

- Bicho, N.; Cascalheira, J.; Gonçalves, C. (2017). "Early Upper Paleolithic colonization across Europe: Time and mode of the Gravettian diffusion". PLoS One. 12 (5): e0178506. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0178506. PMC 5443572. PMID 28542642.

- Péan, S.; Puaud, S.; et al. (2013). "The Middle to Upper Paleolithic Sequence of Buran-Kaya III (Crimea, Ukraine): New Stratigraphic, Paleoenvironmental, and Chronological Results". 55 (2–3). doi:10.2458/azu_js_rc.55.16379. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Fu, Q.; Posth, C. (2016). "The genetic history of Ice Age Europe". Nature. 534 (7606): 200–205. Bibcode:2016Natur.534..200F. doi:10.1038/nature17993. PMC 4943878. PMID 27135931.

- Lazaridis, I; Patterson, Nick (2014). "Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans". Nature. 513 (7518): 409–13. arXiv:1312.6639. Bibcode:2014Natur.513..409L. doi:10.1038/nature13673. hdl:11336/30563. PMC 4170574. PMID 25230663. Supplemental Information 14; Extended Data Figure 6

- Lazaridis, I.; Patterson, N.; et al. (2014). "Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans". Nature. 513: 409–413. doi:10.1038/nature13673.

- Lipson (2017). "Parallel palaeogenomic transects reveal complex genetic history of early European farmers". Nature. 551 (7680): 368–72. Bibcode:2017Natur.551..368L. doi:10.1038/nature24476. PMC 5973800. PMID 29144465.

- Haak, W.; Lazaridis, I.; et al. (2015). "Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". Nature. 522: 207–211. doi:10.1038/nature14317.

- "Knowing ourselves". Nature Ecology and Evolution. 2: 1517–1518. 2018. doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0675-3.

- Lartet, L. (1868). "Une sépulture des troglodytes du Périgord (crânes des Eyzies)" [A grave of cave dwellers in Périgord (Les Eyzies skulls)]. Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d'Anthropologie de Paris (in French). 3: 335–349.

- McMahon, R. (2016). The Races of Europe: Construction of National Identities in the Social Sciences, 1839-1939. Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-31846-6. ISBN 978-1-137-31846-6.

- Fagan, B. (2011). "Momentous Encounters". Cro-Magnon: How the Ice Age Gave Birth to the First Modern Humans. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-1-60819-405-6.

- Notton, D. G.; Stringer, C. B. (2010). "Who is the type of Homo sapiens?". International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Romeo, L. (1979). Ecce Homo!: A Lexicon of Man. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-272-2006-6.

- Formicola, V.; Giannecchini, M. (1998). "Evolutionary trends of stature in Upper Paleolithic and Mesolithic Europe". Journal of Human Evolution. 36 (3): 319–333. doi:10.1006/jhev.1998.0270. PMID 10074386.

- Balzeau, A.; Grimaud-Hervé, D.; Detroit, F.; Holloway, R. L. (2013). "First description of the Cro-Magnon 1 endocast and study of brain variation and evolution in anatomically modern Homo sapiens". Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d anthropologie de Paris. 25 (1–2): 11–12. doi:10.1007/s13219-012-0069-z.

- Lieberman, D. E. (1998). "Sphenoid shortening and the evolution of modern human cranial shape". Nature. 393: 158–162. doi:10.1038/30227.

- Haviland, W. A.; Prins, H. E L.; Walrath, D.; McBride, B. (2010). Anthropology: The Human Challenge. Cengage Learning. pp. 204–205, 212. ISBN 978-0-495-81084-1.

- Koehl, Dan. "The Cro Magnon man (Homo sapiens sapiens) Anatomically Modern or Early Modern Humans". elephant.se. Grolier Multimedia Encyclopedia.

- Allentoft, M. E.; Sikora, M. (2015). "Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia". Nature. 522 (7, 555): 167–172. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..167A. doi:10.1038/nature14507. PMID 26062507.

- Beleza, S.; et al. (2012). "The Timing of Pigmentation Lightening in Europeans". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 30: 24–35. doi:10.1093/molbev/mss207. PMC 3525146. PMID 22923467.

- Eiberg, H.; Troelson, J.; et al. (2008). "Blue eye color in humans may be caused by a perfectly associated founder mutation in a regulatory element located within the HERC2 gene inhibiting OCA2 expression". Human Genetics. 123: 177–188. doi:10.1007/s00439-007-0460-x.

- Jones, E.R. (2015). "Upper Palaeolithic genomes reveal deep roots of modern Eurasians". Nature Communications. 6: 8912. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.8912J. doi:10.1038/ncomms9912. PMC 4660371. PMID 26567969.

- Kuhlwilm, M.; Gronau, I.; Hubisz, M. J.; de Filippo, C.; Prado-Martinez, J.; Kircher, M.; et al. (2016). "Ancient gene flow from early modern humans into Eastern Neanderthals". Nature. 530 (7591): 429–433. Bibcode:2016Natur.530..429K. doi:10.1038/nature16544. PMC 4933530. PMID 26886800.

- Sankararaman, S.; Patterson, N.; Li, H.; Pääbo, S.; Reich, D.; Akey, J. M. (2012). "The Date of Interbreeding between Neandertals and Modern Humans". PLoS Genetics. 8 (10): e1002947. arXiv:1208.2238. Bibcode:2012arXiv1208.2238S. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002947. PMC 3464203. PMID 23055938.

- Fu, Q.; Hajdinjak, M.; Moldovan, O. T.; Constantin, S.; Mallick, S.; Skoglund, Pontus; Patterson, N.; Rohland, N.; Lazaridis, I.; Nickel, B.; Viola, B.; Prüfer, Kay; Meyer, M.; Kelso, J.; Reich, D; Pääbo, S. (2015). "An early modern human from Romania with a recent Neanderthal ancestor". Nature. 524 (7564): 216–219. Bibcode:2015Natur.524..216F. doi:10.1038/nature14558. PMC 4537386. PMID 26098372.

- Posth, Cosimo; et al. (4 July 2017). "Deeply divergent archaic mitochondrial genome provides lower time boundary for African gene flow into Neanderthals". Nature Communications. 8: 16046. Bibcode:2017NatCo...816046P. doi:10.1038/ncomms16046. PMC 5500885. PMID 28675384.

- Soares, P.; et al. (2011). "The Expansion of mtDNA Haplogroup L3 within and out of Africa". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 29 (3): 915–927. doi:10.1093/molbev/msr245. PMID 22096215.

- Higham, Thomas F. G.; Wesselingh, Frank P.; Hedges, Robert E. M.; Bergman, Christopher A.; Douka, Katerina (2013-09-11). "Chronology of Ksar Akil (Lebanon) and Implications for the Colonization of Europe by Anatomically Modern Humans". PLOS ONE. 8 (9): e72931. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...872931D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0072931. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3770606. PMID 24039825.

- Caramelli, D.; Lalueza-Fox, C.; Vernesi, C.; Lari, M.; Casoli, A.; Mallegni, F.; Chiarelli, B.; Dupanloup, I.; Bertranpetit, J.; Barbujani, G.; Bertorelle, G. (May 2003). "Evidence for a genetic discontinuity between Neandertals and 24,000-year-old anatomically modern Europeans". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 100 (11): 6593–6597. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.6593C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1130343100. PMC 164492. PMID 12743370.

- Maca-Meyer N, González AM, Larruga JM, Flores C, Cabrera VM (2001). "Major genomic mitochondrial lineages delineate early human expansions". BMC Genet. 2: 13. doi:10.1186/1471-2156-2-13. PMC 55343. PMID 11553319.

- Bar-Yosef, O. (2002). "The Upper Paleolithic Revolution". Annual Review of Anthropology: 363–369. JSTOR 4132885.

- Bar-Yosef, O & Zilhão, J (eds) 2002: Towards a definition of the Aurignacian. Proceedings of the Symposium held in Lisbon, Portugal, June 25–30. Trabalhos de Arqueologia no 45. 381 pp. PDF

- Deter-Wolf, A. (2013). "The Material Culture and Middle Stone Age Origins of Ancient Tattooing". Tattoos and Body Modifications in Antiquity. Chronos Verlag. pp. 17–18.

- Knecht, H. (1994). "Late Ice Age Hunting Technology". Scientific American. 271 (1): 82–87. JSTOR 24942770.

- Straus, L. G. (1993). "Upper Paleolithic Hunting Tactics and Weapons in Western Europe". Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association. 4 (1): 83–93. doi:10.1525/ap3a.1993.4.1.83.

- Zohar, I.; Dayan, T.; Goren, M.; Nadel, D.; Hershkovitz, I. (2018). "Opportunism or aquatic specialization? Evidence of freshwater fish exploitation at Ohalo II- A waterlogged Upper Paleolithic site". PLoS One. 13 (6): e0198747. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0198747. PMC 6005578. PMID 29912923.

- Bahn, P. G. (1977). "Seasonal migration in South-west France during the late glacial period". Journal of Archaeological Science. 4 (3): 245–257. doi:10.1016/0305-4403(77)90092-9.

- Tomasso, A.; Rots, V.; Purdue, L.; Beyries, S. (2018). "Gravettian weaponry: 23,500-year-old evidence of a composite barbed point from Les Prés de Laure (France)". Journal of Archaeological Science. 100: 158–175. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2018.05.003.

- Thalmann, O.; Shapiro, B.; Cui, P.; Schuenemann, V. J.; Sawyer, S. K.; et al. (2013). "Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Ancient Canids Suggest a European Origin of Domestic Dogs". Science. 342 (6160): 871–874. Bibcode:2013Sci...342..871T. doi:10.1126/science.1243650. PMID 24233726. refer Supplementary material Page 27 Table S1

- Janssens, Luc; Giemsch, Liane; Schmitz, Ralf; Street, Martin; Van Dongen, Stefan; Crombé, Philippe (2018). "A new look at an old dog: Bonn-Oberkassel reconsidered". Journal of Archaeological Science. 92: 126–138. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2018.01.004. hdl:1854/LU-8550758.

- Nadel, D.; Weiss, E.; Simchoni, O.; et al. (2004). "Stone Age hut in Israel yields world's oldest evidence of bedding". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (17): 6821–6826. doi:10.1073/pnas.0308557101.

- Lister, A.; Bahn, P. (2007). Mammoths – Giants of the Ice Age (3 ed.). Frances Lincoln. pp. 128–132. ISBN 978-0-520-26160-0. OCLC 30155747.

- Pidoplichko, I. H. (1998). Upper Palaeolithic dwellings of mammoth bones in the Ukraine: Kiev-Kirillovskii, Gontsy, Dobranichevka, Mezin and Mezhirich. Oxford: J. and E. Hedges. ISBN 978-0-86054-949-9.

- Pryor, A. J. E.; Beresford-Jones, D. G.; Dudin, A. E.; et al. (2020). "The chronology and function of a new circular mammoth-bone structure at Kostenki 11". Antiquity. 94 (374): 323–341. doi:10.15184/aqy.2020.7.

- Demay, L.; Péan, S.; Patou-Mathis, M. (2012). "Mammoths used as food and building resources by Neanderthals: Zooarchaeological study applied to layer 4, Molodova I (Ukraine)" (PDF). Quaternary International. 276–277: 212–226. Bibcode:2012QuInt.276..212D. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2011.11.019.

- McDermott, L. (1996). "Self-Representation in Upper Paleolithic Female Figurines". Current Anthropology. 37 (2): 231–235. JSTOR 2744349.

- Soffer, O.; Adovasio, J. M.; Hyland, D. C. (2000). "The "Venus" Figurines: Textiles, Basketry, Gender, and Status in the Upper Paleolithic". Current Anthropology. 41 (4): 512–521. doi:10.1086/317381.

- Angulo, J. C.; García-Díez, M.; Martínez, M. (2010). "Phallic Decoration in Paleolithic Art: Genital Scarification, Piercing and Tattoos". Journal of Urology. 186: 2498–2503. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2011.07.077.

- Floss, H. (2015). "The Oldest Portable Art: the Aurignacian Ivory Figurines from the Swabian Jura (Southwest Germany)". Palethnologie. doi:10.4000/palethnologie.888.

- Marshack, A. (1972). "Cognitive Aspects of Upper Paleolithic Engraving". Current Anthropology. 13 (3–4): 445–477. JSTOR 2740829.

- Wolf, S.; Dapschauskas, R.; et al. (2018). "The Use of Ochre and Painting During the Upper Paleolithic of the Swabian Jura in the Context of the Development of Ochre Use in Africa and Europe". Open Archaeology. 4 (1): 185–205. doi:10.1515/opar-2018-0012.

- Vanhaeren, M.; d'Errico, F. (2006). "Aurignacian ethno-linguistic geography of Europe revealed by personal ornaments". Journal of Archaeological Science. 33: 1105–1128.

- Kuhn, S. L.; Stiner, M. C. (2007). "Paleolithic Ornaments: Implications for Cognition, Demography and Identity". Diogenes. 214: 40–48. doi:10.1177/0392192107076870.

- Kvavadze E; Bar-Yosef O; Belfer-Cohen A; et al. (September 2009). "30,000-year-old wild flax fibers". Science. 325 (5946): 1359. Bibcode:2009Sci...325.1359K. doi:10.1126/science.1175404. PMID 19745144. Supporting Online Material

- Killin, A. (2018). "The origins of music: Evidence, theory, and prospects". Music and Science. 1: 5–7. doi:10.1177/2059204317751971.

- Pagel, M.; Atkinson, Q. D.; Calude, A. S.; Meade, A. (2013). "Ultraconserved words point to deep language ancestry across Eurasia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (21): 8471–8476. doi:10.1073/pnas.1218726110.

- Heggarty, P. (2013). "Ultraconserved words and Eurasiatic? The "faces in the fire" of language prehistory". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (35): E3254. doi:10.1073/pnas.1309114110.

- Walter, E. V. (1988). Placeways: A Theory of the Human Environment. UNC Press Books. pp. 89–94. ISBN 978-0-8078-4200-3.

- Yusoff, K. (2015). "Geologic subjects: nonhuman origins, geomorphic aesthetics and the art of becoming inhuman". Cultural Geographies. 22 (3): 386. JSTOR 26168658.