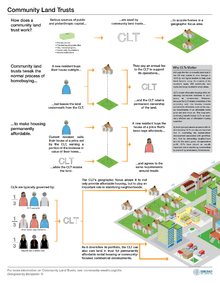

Community land trust

A community land trust (CLT) is a nonprofit corporation that develops and stewards affordable housing, community gardens, civic buildings, commercial spaces and other community assets on behalf of a community. “CLTs” balance the needs of individuals to access land and maintain security of tenure with a community’s need to maintain affordability, economic diversity and local access to essential services.

Historical overview

The community land trust (CLT) is a model of affordable housing and community development that has slowly spread throughout the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom over the past 40 years. The model was originated in the United States by Ralph Borsodi and Robert Swann, drawing upon earlier examples of planned communities on leased land including the Garden city movement in the United Kingdom, single tax communities in the US, Gramdan villages in India, and moshav communities on lands owned by the Jewish National Fund in Israel. New Communities, Inc., the prototype for the modern-day community land trust, was formed in 1969 near Albany, Georgia, by leaders of the Civil Rights Movement who were seeking a new way to achieve secure access to land for African American farmers.

History

According to the Schumacher Center for a New Economics website, "Swann was inspired by Ralph Borsodi and by Borsodi's work with J. P. Narayan and Vinoba Bhave, both disciples of Gandhi. Vinoba walked from village to village in rural India in the 1950s and 1960s, gathering people together and asking those with more land than they needed to give a portion of it to their poorer sisters and brothers. The initiative was known as the Bhoodan or Land gift movement, and many of India's leaders participated in these walks.

Some of the new landowners, however, became discouraged. Without tools to work the land and seeds to plant it, without an affordable credit system available to purchase these necessary things, the land was useless to them. They soon sold their deeds back to the large landowners and left for the cities. Seeing this, Vinoba altered the Boodan system to a Gramdan or Village gift system. All donated land was subsequently held by the village itself. The village would then lease the land to those capable of working it. The lease expired if the land was unused. The Gramdan movement inspired a series of regional village land trusts that anticipated Community Land Trusts in the United States.

The first organization to be labeled with the term 'community land trust' in the U.S., called New Communities, Inc., was founded with the purpose of helping African-American farmers in the rural South to gain access to farmland and to work it with security.

A precursor to this was the Celo Community in North Carolina, which was founded in 1937 by Arthur Ernest Morgan.[1]

New Communities

The vision

Robert Swann worked with Slater King, president of the Albany Movement and a cousin of Martin Luther King, Jr., Charles Sherrod, an organizer for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, his wife Shirley Sherrod, and individuals from other southern civil rights organizations in the South to develop New Communities, Inc., "a nonprofit organization to hold land in perpetual trust for the permanent use of rural communities".

Their vision for New Communities Inc. drew heavily on the example and experience of the Jewish National Fund (JNF) in making land available through 99-year ground leases for the development of planned communities and agricultural cooperatives. The JNF was founded in 1901 to buy and develop land in Ottoman Palestine (later Israel) for Jewish settlement. By 2007, the JNF owned 13% of all the land in Israel. It has a long and established legal history of leasing land to individuals, to cooperatives, and to intentional communities such as kibbutzim and moshavim. Swann, Slater King, Charles Sherrod, Faye Bennett, director of the National Sharecroppers Fund, and four other Southerners travelled to Israel in 1968 to learn more about ground leasing. They decided on a model that included individual leaseholds for homesteads and cooperative leases for farmland. New Communities Inc. purchased a 5,000-acre (20 km2) farm near Albany, Georgia in 1970, developed a plan for the land, and farmed it for 20 years. The land was eventually lost as a result of USDA racial discrimination, but the example of New Communities inspired the formation of a dozen other rural community land trusts in the 1970s. It also inspired and informed the first book about community land trusts, produced by the International Independence Institute in 1972.

Founding the International Independence Institute

Ralph Borsodi, Robert Swann, and Erick Hansch founded the International Independence Institute in 1967 to provide training and technical assistance for rural development in the United States and other countries, drawing on the model of the Gramdan villages being developed in India. In 1972, Swann, Hansch, Shimon Gottschalk, and Ted Webster proposed a "new model for land tenure in America" in The Community Land Trust, the first book to name and describe this new approach to the ownership of land, housing, and other buildings. One year later, they changed the name of the International Independence Institute to the Institute for Community Economics (ICE).

In the 1980s, ICE began popularizing a new notion of the CLT, applying the model for the first time to problems of affordable housing, gentrification, displacement, and neighborhood revitalization in urban areas. From 1980–1990, Chuck Matthei, an activist with roots in the Catholic Worker movement and the peace movement, served as Executive Director of ICE, then based in Greenfield, MA and now an affiliate of the National Housing Trust and located in Washington, DC. ICE pioneered the modern community land trust and community loan fund models.

The model spreads

Under Matthei's tenure, the number of community land trusts increased from a dozen to more than 100 groups in 23 states, creating many hundreds of permanently affordable housing units, as well as commercial and public service facilities. With colleagues Matthei guided the development of 25 regional loan funds and organized the National Association of Community Development Loan Funds, later known as the National Community Capital Association. From 1985–1990, Matthei served as a founding Chairman of the Association and from 1983–1988 he served as a founding board member of the Social Investment Forum, the national professional association in the field of socially responsible investment. Matthei also launched an effort in the early to mid-1980s to address many of the legal and operational questions about CLTs that were arising as banks, public officials and1 by an ecumenical association of churches and ministries created to prevent the displacement of low-income, African-American residents from their neighborhood.

During the 1980s, the number of urban CLTs increased dramatically. They were sometimes formed, as in Cincinnati, in opposition to the plans and politics of municipal government. In other cities, like Burlington, Vermont and Syracuse, New York, community land trusts were formed in partnership with a local government. One of the most significant city-CLT partnerships was formed in 1989 when a CLT subsidiary of the Dudley Neighborhood Initiative was granted the power of eminent domain by the City of Boston. others encountered the growing effort to create such community-based organizations around the country. The first urban CLT, the Community Land Cooperative of Cincinnati, was founded in 1981.[2]

One of the earliest and most influential is the Burlington Community Land Trust (BCLT) in Vermont, which was organized in the early 1980s as a response to rapidly increasing housing costs that threatened to price out many long term residents of the city. BCLT is now known as the Champlain Housing Trust (CHT). CHT owns the underlying land but residents of CHT own the house or unit in which they live. Residents of CHT pay no more than 30% of their income in rent or mortgage payments, and resale prices of units cannot increase more than a previously specified percentage so that future generations of low income and moderate income people can also afford to live in the development.[3][4] Half of CHT's units are in Burlington, and half outside. CHT has provided a substantial increase in the Burlington area's affordable housing stock, with CHT units comprising 7.6% of total housing in Burlington.[5]

International scope

There are currently over 250 community land trusts in the United States. In 2006, a national association was established in the United States to provide assistance and support for CLTs: the National Community Land Trust Network.

Also established that year to serve as the Network’s training and research arm was the National CLT Academy. Fledgling CLT movements are also underway in England, Canada, Australia, Belgium, Kenya and New Zealand. Similar nationwide networks for promoting and supporting CLTs have recently been formed in the United Kingdom and in Australia.

Defining features in the United States

Since 1992, the defining features of the CLT model in the United States have been enshrined in federal law (Section 213, Housing and Community Development Act of 1992). There is considerable variation among the hundreds of organizations that call themselves a community land trust, but ten key features are to be found in most of them.

Nonprofit, tax-exempt corporation

A community land trust is an independent, nonprofit corporation that is legally chartered in the state in which it is located. Most CLTs are started from scratch, but some are grafted onto existing nonprofit corporations such as community development corporations. Most CLTs target their activities and resources toward charitable activities like providing housing for low-income people and redeveloping blighted neighborhoods, making them eligible to receive 501(c)(3) designation from the IRS.

Dual ownership

A nonprofit corporation, the CLT, acquires multiple parcels of land throughout a targeted geographic area with the intention of retaining ownership of the parcels forever. Any building already located on the land or later constructed on the land can be held by the CLT or sold off to an individual homeowner, a cooperative housing corporation, a nonprofit developer of rental housing, or some other nonprofit, governmental, or for-profit entity.[6]

Leased land

Although CLTs intend never to resell their land, they can provide for the exclusive use of their land by the owners of any buildings located thereon. Exclusive use of parcels of land can be conveyed to individual homeowners or to the owners of other types of residential or commercial structures by long-term ground leases. The two-party contract between the landowner (the CLT) and a building's owner protects the owner's interests in security, privacy, legacy, and equity and enforces the CLT's interests in preserving the appropriate use, the structural integrity and the continuing affordability of any buildings on its land.

Perpetual affordability

The CLT retains an option to repurchase any residential (or commercial) structures on its land if their owners ever choose to sell. The resale price is set by a formula contained in the ground lease that is designed to give present homeowners a fair return on their investment but giving future homebuyers fair access to housing at an affordable price. By design and by intent, the CLT is committed to preserving the affordability of housing (and other structures), one owner after another, one generation after another, in perpetuity.

Perpetual responsibility

The CLT does not disappear once a building is sold. As owner of the underlying land and as owner of an option to repurchase any buildings located on its land, the CLT has an abiding interest in what happens to the structures and to the people who occupy them. The ground lease requires owner-occupancy and responsible use of the premises. Should buildings become a hazard, the ground lease gives the CLT the right to step in and force repairs. Should property owners default on their mortgages, the ground lease gives the CLT the right to step in and cure the default, forestalling foreclosure. The CLT remains a party to the deal, safeguarding the structural integrity of the buildings and the residential security of the occupants.

Community base

The CLT operates within the physical boundaries of a targeted locality. It is guided by and accountable to the people who live in it. Most commonly, any adult who resides on the CLT's land and any adult who resides within the area deemed by the CLT to be its community can become a voting member of the CLT. The community may encompass a single neighborhood, multiple neighborhoods, or, in some cases, an entire town, city, or county.

Governance

Typically, CLTs are run by a board of directors whose members include three groups of stakeholders: residents or leaseholders, people who reside within its targeted community but do not live on its land, and lastly the broader public interest. This third group is frequently represented by government officials, funders, housing agencies, and social service providers. Organization bylaws may designate each of these groups a specific and equal number of seats, and they may be elected separately by their constituent groups.[7][8][9][10][11] Control of the CLT’s board is diffused and balanced to ensure that all interests are heard but that no interest predominates.

Expansionist acquisition

CLTs are not focused on a single project located on a single parcel of land. They are committed to an active acquisition and development program aimed at expanding the CLT's holdings of land and increasing the supply of affordable housing (and other types of buildings) under the CLT's stewardship. A CLT's holdings are seldom concentrated in one corner of a community but tend to be scattered throughout its service area, indistinguishable from other owner-occupied housing in the same neighborhood.

Flexible development

There is enormous variability in the types of projects that CLTs pursue and in the roles they play in developing them. Many CLTs do development with their own staff. Others delegate development to nonprofit or for-profit partners, confining their own efforts to assembling land and preserving the affordability of any structures located upon it. Some CLTs focus on a single type and tenure of housing, like detached, owner-occupied houses. Others take full advantage of the model’s unique flexibility. They develop housing of many types and tenures or they focus more broadly on comprehensive community development, undertaking a diverse array of residential and commercial projects. CLTs around the country have constructed (or acquired, rehabilitated, and resold) single-family homes, duplexes, condos, co-ops, SROs, multi-unit apartment buildings, and mobile home parks. CLTs have created facilities for neighborhood businesses, nonprofit organizations, and social service agencies. CLTs have provided sites for community gardens, vest-pocket parks, and affordable working land for entry-level agriculturalists. Permanently affordable access to land is the common ingredient, linking them all. The CLT is the social thread, connecting them all.

Community land trusts in the United Kingdom

In Scotland, the community land movement is well established and supported by government. Members of Community Land Scotland own or manage over 500,000 acres of land, home to over 25,000 people.

There are currently 255 CLTs in England and Wales, with over 17,000 members and 935 homes.[12] The movement has grown rapidly since 2010, when pioneer CLTs and supporters established the National CLT Network for England and Wales. CLTs were defined in English law in section 79 of the Housing and Regeneration Act 2008.

CLTs in the UK share most of the defining features with CLTs in the United States. But they have tended to have a greater focus on the participation of their local members and community-level democracy, and are more likely to emerge as grassroots citizen initiatives. In Scotland they are also associated with communities reclaiming land from absentee aristocratic landowners.

Development elsewhere

Fledgling CLT movements are also underway in:

- Canada,

- Australia,

- Belgium,

- France,

- Kenya,

- New Zealand.[13]

Other Names for Community Land Trusts

In the United States, Community Land Trusts may also be referred to as:

See also

References

- Hicks, George L. Experimental Americans: Celo and Utopian Community in the Twentieth Century. University of Illinois Press: 2001.

- "Community Land Cooperative of Cincinnati (CLCC)". Retrieved December 16, 2017.

- Gar Alperovitz, "America Beyond Capitalism: Reclaiming Our Wealth, Our Liberty, and Our Democracy," (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2005), p. 94

- New York University (NYU), Wagner, Research Center for Leadership in Action, "Enabling Low-Income Families to Buy Their Own Homes While Holding The Land in Trust for the Community"

- Slate, 19 Jan. 2016, "How Bernie Sanders Made Burlington Affordable: As the City’s Mayor in The 1980s, He Championed an Unusual Model of Publicly Supported Housing. It’s Still Working"

- Semuels, Alana (July 7, 2015). "Affordable Housing, Always". The Atlantic.

- "Community Land Trust Models and Housing Coops from Around the World". Resilience. 29 March 2017.

Like many other CLTs, the CHT has a governing board divided in thirds and elected by residents: one-third of its membership is constituted by CHT residents; another third from surrounding communities; and the final third is comprised of municipal officials and a regional representative who are presumed to speak for the public interest (in other CLTs this final third is often comprised of technical specialists like engineers, accountants, planners, architects, social workers or lawyers

- "The Favela as a Community Land Trust: A Solution to Eviction and Gentrification? - RioOnWatch".

CLT trusts are usually divided into thirds, where one third of the trust leadership is residents from the CLT community, one third is people from the neighborhood surrounding the CLT, and one third is made up of technical experts and municipal officials who provide particular expertise (legal, architectural, engineering, political, etc.) and speak in the general public interest

- "Community Land Trusts explained". Prosper Australia.

those representing resident members, those representing members who are not CLT residents, and those representing the broader community interest here members includes neighbors who are interested, supportive, or may become residents

- "Home". Grounded Solutions Network.

CLTs are nonprofit organizations—governed by a board of CLT residents, community residents and public representatives

- "Saratoga Community Housing – What is a Community Land Trust?". saratogacommunityhousing.org. Archived from the original on 27 October 2016.

residents of trust owned lands, other community members and public-interest representatives

- "About CLTs". National CLT Network. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- New Zealand Archived 2011-11-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Kelly, Jr., J.J. "Maryland's Affordable Housing Land Trust Act" (PDF). CLT Network. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- Minn. Stat. § 462A.31

Further reading

Books

- The Community Land Trust: A Guide to a New System of Land Tenure in America original 1972 book authored by Robert Swann et al. in pdf form

- The Community Land Trust Handbook, authored by the Institute for Community Economics and published by Rodale Press in 1982.

- Streets of Hope: The Fall and Rise of an Urban Neighborhood, authored by Peter Medoff and Holly Sklar and published by South End Press in 1994.

- Starting a Community Land Trust: Organizational and Operational Choices, a 2007 publication authored by John Emmeus Davis and available on line at https://web.archive.org/web/20070203135657/http://www.burlingtonassociates.com/resources/

- The City-CLT Partnership: Municipal Support for Community Land Trusts, authored by John Emmeus Davis and Rick Jacobus and published by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy in 2008.

- The Community Land Trust Reader, edited by John Emmeus Davis and published by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy in 2010.

- Building sustainable communities from the grassroots: How community land trusts can create social sustainability by Nick Bailey. In T. Manzi, K. Lucas, T. Lloyd-Jones, and J. Allen (eds.) Understanding Social Sustainability, London: Earthscan, 49–64.2010.

Articles

- Community Land Trusts: An Introduction, by Tom Peterson

- "Burlington Busts the Affordable Housing Debate" Discussion of community land trust program in Burlington, VT

- Community Land Trusts: Protecting the Land Commons, by David Harper

- Community Land Trusts in England, by Dave Smith

- Wainwright, Oliver (16 January 2017). "The radical model fighting the housing crisis: property prices based on income". The Guardian.

External links

- Grounded Solutions Network (USA) (a merger involving the National Community Land Trust Network)

- National Community Land Trust Network (England and Wales)

- Institute for Community Economics

- CLT Resources, Burlington Associates in Community Development, LLC

- New Economics Institute in the United States (formerly E. F. Schumacher Society) page with information on CLTs

- Equity Trust, Inc. has promoted the use of community land trusts in preserving working farms and securing land for community supported agriculture.

- Beer Community Land Trust established in 2013 to facilitate the development of affordable housing at 80% of the prevailing market prices for local people in the village of Beer, Devon, United Kingdom.

- The Madison Area Community Land Trust is the developer and steward of Troy Gardens, a nationally recognized project that combines affordable housing, community gardens, and urban agriculture.

- The San Francisco Community Land Trust

- The Champlain Housing Trust, currently the largest community land trust in the United States, serving a three-county area in northwestern Vermont and managing a portfolio of over 2,000 units of affordable housing.

- The Northwest Community Land Trust Coalition

- CLT East, Professional advice and technical support in the East of England for community land trusts.

- Proud Ground, the Northwest's largest community land trust, serving the Portland Metropolitan area

- Minnesota Community Land Trust Coalition

- The Northern California Land Trust, the oldest CLT in California

- London Community Land Trust The first community land trust in London, organising communities to deliver affordable homes

- School of Living Supports the development of community land trusts in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States

Australia. www.macll.org.au

- Community Land Trust Brussels Community Land Trust Brussels