Clipperton Island

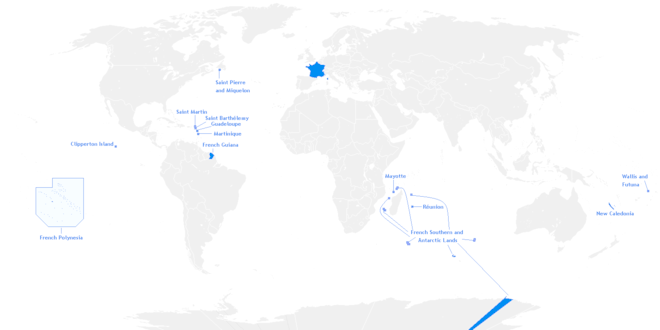

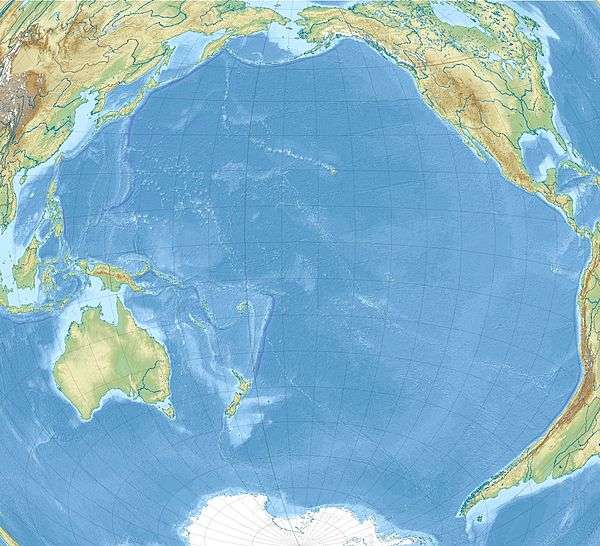

Clipperton Island (French: Île de Clipperton or Île de la Passion; Spanish: Isla de la Pasión) is an uninhabited 6 km2 (2.3 sq mi) coral atoll in the eastern Pacific Ocean off the coast of Central America. It is 10,677 km (6,634 mi) from Paris, France, 5,400 km (2,900 nmi) from Papeete, Tahiti, and 1,080 km (580 nmi) from Mexico. It is an overseas state private property of France, under direct authority of the Minister of Overseas France.[1][2]

| Native name: Île de Clipperton, Isla de la Pasión | |

|---|---|

.svg.png) Clipperton Atoll with lagoon with depths (meters) | |

Clipperton | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 10°18′N 109°13′W |

| Archipelago | Lagoon |

| Area | 6 km2 (2.3 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 29 m (95 ft) |

| Highest point | Clipperton Rock |

| Administration | |

| State private property | Île de Clipperton |

| Demographics | |

| Population | Non Applicable (1945) |

| Additional information | |

| Time zone | |

| Official website | L’île de Clipperton |

Geography

| Clipperton Island | Area |

|---|---|

| Land | 2 km2 (0.77 sq mi) |

| Land + Lagoon | 6 km2 (2.3 sq mi) |

| EEZ | 431,273 km2 (166,515 sq mi) |

The atoll is 1,080 km (583 nmi) south-west of Mexico, 2,424 km (1,309 nmi) west of Nicaragua, 2,545 km (1,374 nmi) west of Costa Rica and 2,260 km (1,220 nmi) north-west of the Galápagos Islands, Ecuador, at 10°18′N 109°13′W. Clipperton is about 945 km (510 nmi) south-east of Socorro Island in the Revillagigedo Archipelago, which is the nearest land while the nearest French-owned island is Hiva Oa.

It is low-lying and largely barren, with some scattered grasses and a few clumps of coconut palms (Cocos nucifera). Land elevations average 2 m (6.6 ft), though a small volcanic outcrop rising to 29 m (95 ft) on its south-east side is considerably higher and is referred to as "Clipperton Rock".[3] The surrounding reef is exposed at low tide.[4] The presence of this rock means that technically Clipperton is not an atoll but an island with a barrier reef.

Clipperton has had no permanent inhabitants since 1945. It is visited on occasion by fishermen, French Navy patrols, scientific researchers, film crews, and shipwreck survivors. It has become a popular site for transmissions by ham radio operators.[5]

Environment

Lagoon and climate

Clipperton has a ring-shaped atoll which completely encloses a stagnant fresh water lagoon, and is 12 km (7.5 mi) in circumference. The lagoon is devoid of fish, and contains some deep basins with depths of 43 and 72 m (141 and 236 ft), including a spot known as Trou-Sans-Fond, or "the bottomless hole", with acidic water at its base. The water is described as being almost fresh at the surface, and highly eutrophic. Seaweed beds cover approximately 45 percent of the lagoon's surface. The rim averages 150 m (490 ft) in width, reaching 400 m (1,300 ft) in the west and narrows to 45 m (148 ft) in the north-east, where sea waves occasionally spill over into the lagoon.[4]

While some sources have rated the lagoon water as non-potable,[6][7] testimony from the crew of the tuna clipper M/V Monarch, stranded for 23 days in 1962 after their boat sank, indicates otherwise. Their report reveals that the lagoon water, while not tasting very good, was drinkable, though "muddy and dirty". Several of the castaways drank it, with no apparent ill effects.[8]

Survivors of an ill-fated Mexican military colony in 1917 (see below) indicated that they were dependent upon rain for their water supply, catching it in old boats they used for this purpose.[8] Aside from the lagoon and water caught from rain, no other freshwater sources are known to exist.

It has a tropical oceanic climate, with average temperatures of 20–32 °C (68–90 °F). The rainy season occurs from May to October, when it is subject to tropical storms and hurricanes. Surrounding ocean waters are warm, pushed by equatorial and counter-equatorial currents. It has no known natural resources (its guano having been depleted early in the 20th century). Although 115 species of fish have been identified in nearby waters the only economic activity in the area is tuna fishing.

Flora and fauna

When Snodgrass and Heller visited in 1898, they reported that "no land plant is native to the island".[9] Historical accounts from 1711, 1825, and 1839 show a low grassy or suffrutescent (partially woody) flora. During Sachet's visit in 1958, the vegetation was found to consist of a sparse cover of spiny grass and low thickets, a creeping plant (Ipomoea spp.), and stands of coconut palm. This low-lying herbaceous flora seems to be a pioneer in nature, and most of it is believed to be composed of recently introduced species. Sachet suspected that Heliotropium curassavicum and possibly Portulaca oleracea were native. Coconut palms and pigs were introduced in the 1890s by guano miners. The pigs reduced the crab population, which in turn allowed grassland to gradually cover about 80 percent of the land surface.[10] The elimination of these pigs in 1958 — the result of a personal project by Kenneth E. Stager[11] — has caused most of this vegetation to disappear, as the population of land crabs (Johngarthia planata) has returned to millions.[12] The result is virtually a sandy desert, with only 674 palms counted by Christian Jost during the "Passion 2001" French mission, and five islets in the lagoon with grass that the terrestrial crabs cannot reach.

On the north-west side the most abundant plant species are Cenchrus echinatus, Sida rhombifolia, and Corchorus aestuans. These plants compose a shrub cover up to 30 cm in height and are intermixed with Eclipta, Phyllanthus, and Solanum, as well as a taller plant, Brassica juncea. A unique feature is that the vegetation is arranged in parallel rows of species, with dense rows of taller species alternating with lower, more open vegetation. This was assumed to be a result of the phosphate mining method of trench-digging.[4]

The only land animals known to exist are two species of reptiles (Gehyra insulensis, a gecko, and Emoia cyanura, a skink),[13] bright-orange land crabs (Johngarthia planata, sometimes known as the 'Clipperton Crab', although it is also found on other islands in the eastern Pacific), birds, and rats. The rats probably arrived on large fishing boats that were wrecked on the island in 1999 and 2000.[11] Bird species include white terns, masked boobies, sooty terns, brown boobies, brown noddies, black noddies, great frigatebirds, coots, martins (swallows), cuckoos and yellow warblers. Ducks have been reported in the lagoon.[4] The island has been identified as an Important Bird Area by BirdLife International because of the large breeding colony of masked boobies, with 110,000 individual birds recorded.[14] The lagoon harbors millions of isopods, which are said to deliver an especially painful sting.[15]

A 2005 report by the NOAA's Southwest Fisheries Science Center indicated that the increased rat presence had led to a decline in both crab and bird populations, causing a corresponding increase in both vegetation and coconut palms. This report urgently recommended eradication of rats so that vegetation might be reduced and the island might return to its "pre-human" state.[11]

History

Discovery and early claims

The island was discovered by Alvaro Saavedra Cedrón on 15 November 1528.[16][17] The expedition was commissioned by Hernán Cortés, the Spanish Conquistador in Mexico, to find a route to the Philippines.

The island was rediscovered on Good Friday, 3 April 1711 by Frenchmen Martin de Chassiron and Michel Du Bocage, commanding the French ships La Princesse and La Découverte. It was given the name Île de la Passion (English: Passion Island); the date of rediscovery fell within Passiontide. They drew up the first map and claimed the island for France. The first scientific expedition took place in 1725 under Frenchman M. Bocage, who lived on the island for several months[18]. In 1858, France formally laid claim.[19]

The current name comes from John Clipperton, an English pirate and privateer who fought the Spanish during the early 18th century, and who is said to have passed by the island. Some sources claim that he used it as a base for his raids on shipping.[20]

Other claimants included the United States, whose American Guano Mining Company claimed it under the Guano Islands Act of 1856; Mexico also claimed it due to activities undertaken there as early as 1848–1849. On 17 November 1858 Emperor Napoleon III annexed it as part of the French colony of Tahiti. This did not settle the ownership question. On 24 November 1897, French naval authorities found three Americans working for the American Guano Company, who had raised the American flag. U.S. authorities denounced their act, assuring the French that they did not intend to assert American sovereignty.[21] Mexico reasserted its claim late in the 19th century, and on 13 December 1897 sent the gunboat La Demócrata to occupy and annex it. A colony was established, and a series of military governors was posted, the last one being Ramón Arnaud (1906–1916).

Final arbitration of ownership

France insisted on its ownership, and a lengthy diplomatic correspondence between Mexico and France led to the conclusion of a treaty on March 2, 1909, to seek binding international arbitration by King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy, with each nation promising to abide by his determination.[22][23]

In 1931, King Victor Emmanuel III issued his arbitral decision in the Clipperton Island Case, declaring Clipperton to be a French possession.[21][24][25][26]

The French rebuilt the lighthouse and settled a military outpost, which remained for seven years before being abandoned.

Guano mining, Mexican colony, and evacuation of 1917

The British Pacific Island Company acquired the rights to guano deposits in 1906 and built a mining settlement in conjunction with the Mexican government. That same year, a lighthouse was erected under the orders of President Porfirio Díaz. By 1914 around 100 people—men, women, and children—were living there, resupplied every two months by a ship from Acapulco. With the escalation of fighting in the Mexican Revolution, the regular resupply visits ceased and the inhabitants were left to their own devices.[27]

By 1917 all but one of the male inhabitants had died. Many had perished from scurvy, while others (including Captain Arnaud) died during an attempt to sail after a passing ship to fetch help. Lighthouse keeper Victoriano Álvarez was the last man on the island, together with 15 women and children.[28] Álvarez proclaimed himself "king" and began a campaign of rape and murder, before being killed by Tirza Rendon, who was the recipient of his unwanted attention. Almost immediately after Álvarez's death four women and seven children, the last survivors, were picked up by the US Navy gunship Yorktown on 18 July 1917.[27] No more attempts were made to colonize it, though it was briefly occupied during the 1930s and 1940s[29][30].

The story of the Mexican colony has been the subject of several novels, including Ivo Mansmann's Clipperton, Schicksale auf einer vergessenen Insel ("Clipperton, Destinies on a Forgotten Island") in German,[31] Colombian writer Laura Restrepo's La Isla de la Pasión ("Passion Island") in Spanish,[32] and Ana Garcia Bergua's Isla de Bobos ("Island of Fools"), also in Spanish.[33]

Post-World War II developments

The island was abandoned by the end of World War II after being briefly occupied by the US from 1944–1945. Since then it has been visited by sports fishermen, patrols of the French Navy, and by Mexican tuna and shark fishermen. There have been infrequent scientific and amateur radio expeditions, and in 1978 Jacques-Yves Cousteau visited with his team of divers and a survivor from the 1917 evacuation to film a television special called Clipperton: The Island that Time Forgot.[34]

It was visited by ornithologist Ken Stager of the Los Angeles County Museum in 1958. Appalled at the depredations visited by feral pigs upon the island's brown booby and masked booby colonies (reduced to 500 and 150 birds, respectively), Stager procured a shotgun and killed all 58 pigs. By 2003, the booby colonies had 25,000 brown boobies and 112,000 masked boobies, the world's second-largest brown booby colony and its largest masked booby colony.[11]

When the independence of Algeria in 1962 threatened French nuclear testing sites in Algeria, the French Ministry of Defense considered Clipperton Island as a possible replacement. This was eventually ruled out due to the island's hostile climate and remote location. The French explored reopening the lagoon and developing a harbor for trade and tourism during the 1970s, but this too was abandoned. An automatic weather installation was completed on 7 April 1980, with data collected by this station transmitted directly by satellite to Brittany.

In 1981, the Academy of Sciences for Overseas Territories recommended that the island have its own economic infrastructure, with an airstrip and a fishing port in the lagoon. This would mean opening up the lagoon by creating a passage in the atoll rim. For this purpose, an agreement was signed with the French government, represented by the High Commissioner for French Polynesia, whereby the island became French state property. In 1986 a meeting took place regarding the establishment of a permanent base for fishing, between the High Commissioner and the survey firm for the development and exploitation of the island (SEDEIC). Taking into account the economic constraints, the distance from markets, and the small size of the atoll, nothing apart from preliminary studies was undertaken. All plans for development were abandoned.

Castaways

In early 1962 the island provided a home to nine crewmen of the sunken tuna clipper MV Monarch, stranded for 23 days from 6 February to 1 March. They reported that the lagoon water was drinkable, though they preferred to drink water from the coconuts they found. Unable to use any of the dilapidated buildings, they constructed a crude shelter from cement bags and tin salvaged from Quonset huts built by the American military 20 years earlier. Wood from the huts was used for firewood, and fish caught off the fringing reef combined with some potatoes and onions they had saved from their sinking vessel augmented the island's meager supply of coconuts. The crewmen reported that they tried eating bird's eggs, but found them to be rancid, and they decided after trying to cook a "little black bird" that it did not have enough meat to make the effort worthwhile. Pigs had been eradicated, though the crewmen reported seeing their skeletons around the atoll. The crewmen were eventually discovered by another fishing boat and rescued by the United States Navy destroyer USS Robison.[8]

In 1988, five Mexican fishermen became lost at sea after a storm during their trip along the coast of Costa Rica. They drifted within sight of the island but were unable to reach it.[35] Steven Longbaugh and David Heritage, two American deckhands from a fishing boat based in California, were stranded for three weeks in 1998. They were rescued after rebuilding a survival radio and using distress flares to signal for help.[36]

21st century

The Mexican and French oceanographic expedition SURPACLIP (UNAM Mexico and UNC Nouméa) made extensive studies in 1997. In 2001, French geographer Christian Jost extended the 1997 studies through his French "Passion 2001" expedition, explaining the evolution of the ecosystem, and releasing several papers, a video film, and a website.[37] In 2003 Lance Milbrand[38] stayed for 41 days on a National Geographic Society expedition, recording his adventure in video, photos, and a written diary (see links below).

In 2005, the ecosystem was extensively studied for four months by a scientific mission organized by Jean-Louis Étienne, which made a complete inventory of mineral, plant, and animal species, studied algae as deep as 100 m (330 ft) below sea level, and examined the effects of pollution. A 2008 expedition from the University of Washington's School of Oceanography collected sediment cores from the lagoon to study climate change over the last millennium.[39]

On 21 February 2007, administration was transferred from the High Commissioner of the Republic in French Polynesia to the Minister of Overseas France.[40]

In 2007 a recreational scuba diving expedition explored the reefs surrounding Clipperton and compared the marine life with the reports of the Connie Limbaugh (Scripps) expeditions in 1956 and 1958. Recreational scuba diving expeditions are now made every spring.

During the night of 10 February 2010, the Sichem Osprey, a Maltese chemical tanker, ran aground on its way from the Panama Canal to South Korea. The 170-meter (560 ft) ship contained xylene, a clear, flammable volatile liquid. All 19 crew members were reported safe, and the vessel reported no leaks.[41][42] The vessel was refloated on 6 March[43] and returned to service.[44]

In mid-March 2012, the crew from The Clipperton Project [45] noted the widespread presence of refuse, particularly on the northeast shore and around the Rock. Debris including plastic bottles and containers create a potentially harmful environment to its flora and fauna. This trash is common to only two beaches (North East and South West) and the rest of the island is fairly clean. Other refuse has been left over after the occupation by the Americans in 1944–1945, the French in 1966–1969 and the 2008 scientific expedition.

Amateur radio DX-peditions

The island has long been an attractive destination for amateur radio groups, due to its remoteness, the difficulty of landing, permit requirements, garish history, and interesting environment. While some radio operation was done ancillary to other expeditions, major DX-peditions include FO0XB (1978), FO0XX (1985), FO0CI (1992), FO0AAA (2000), and TX5C (2008).

One DX-pedition was the Cordell Expedition in March 2013 using the callsign TX5K,[46] organized and led by Robert Schmieder. The project combined radio operations with selected scientific investigations. The team of 24 radio operators made more than 114,000 contacts, breaking the previous record of 75,000. The activity included extensive operation at 6 meters, including EME (Earth–Moon–Earth communication or 'moonbounce') contacts. A notable accomplishment was the use of DXA, a real-time satellite-based online graphic radio log web page that allowed anyone anywhere with a browser to see the radio activity. Scientific work carried out during the expedition included the first collection and identification of foraminifera, and extensive aerial imaging of the island using kite-borne cameras. The team included two scientists from the French-Polynesian University of Tahiti and a TV crew from the French documentary television series Thalassa.[47]

An April 2015 DX-pedition using callsign TX5P was conducted by Alain Duchauchoy, F6BFH, concurrent with the Passion 2015 scientific expedition to Clipperton Island, and engaging in research of Mexican use of the island during the early 1900s.

See also

- Desert island

- List of islands

References

- Article 9 — "Loi n° 55-1052 du 6 août 1955 modifiée portant statut des Terres australes et antarctiques françaises et de l'île de Clipperton" [Law No. 55-1052 of 6 August 1955 on the status of French Southern and Antarctic Lands and Clipperton Island]. LegiFrance (in French). 6 August 1955.

- "Décret du 31 janvier 2008 relatif à l'administration de l'île de Clipperton" [31 January 2008 Order Respecting the Administration of Clipperton Island]. LegiFrance (in French). 31 January 2008.

- "Clipperton Island Pictures and History". 2000 DXpedition to Clipperton Island.

- "Eastern Pacific Ocean, southeast of Mexico". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- "QSLs and Stories from Previous DXpeditions". 2000 DXpedition to Clipperton Island. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- "Clipperton Island". Travel Tips 24. Archived from the original on 2 January 2010.

- Lance Milbrand (29 August 2003). "Clipperton Journal: The daily record of life on a Pacific atoll". National Geographic News.

- Atoll Research Bulletin No. 94 (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences. 15 December 1962. pp. 8–10.

- Snodgrass & Heller (1902).

- Sachet (1962).

- Pitman, Robert L.; Ballance, Lisa T.; Bost, Charly (2005). "Clipperton Island: pigsty, rat hole and booby prize" (PDF). Marine Ornithology. 33 (2): 193–194.

- Davie, P. (2015). Bieler R, Bouchet P, Gofas S, Marshall B, Rosenberg G, La Perna R, Neubauer TA, Sartori AF, Schneider S, Vos C, ter Poorten JJ, Taylor J, Dijkstra H, Finn J, Bank R, Neubert E, Moretzsohn F, Faber M, Houart R, Picton B, Garcia-Alvarez O (eds.). "Johngarthia planata (Stimpson, 1860)". MolluscaBase. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- Zug, George R. (2013). Reptiles and Amphibians of the Pacific Islands: A Comprehensive Guide. University of California Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-520-95540-0.

- BirdLife International (2018). "Important Bird Areas factsheet: Clipperton". BirdLife International. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- Michael Goode. "1992 Clipperton Island Expedition". 2000 DXpedition to Clipperton Island. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- Vargas, Jorge A. (2011). Mexico and the Law of the Sea: Contributions and Compromises. Publications on Ocean Development. 69. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 470. ISBN 9789004206205. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Wright, Ione Stuessy (1953). Voyages of Alvaro de Saavedra Cerón 1527–1529. University of Miami Press.

- "CLIPPERTON ISLAND". Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- Pike, John. "Clipperton / Ile de la Passion". Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- Büch, Boudewijn (2003). Eilanden [Islands] (in Dutch). Netherlands: Singel Pockets. ISBN 978-9-04-133086-4.

- Emmanuel, V. (1932). "Arbitral Award on the Subject of the Difference Relative to the Sovereignty over Clipperton Island" (PDF). The American Journal of International Law. 26 (2): 390–394. doi:10.2307/2189369. JSTOR 2189369.

- "Original treaty between Mexico and France" (PDF). French Foreign Ministry Archives (in French). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2011.

- Dickinson, E. (1933). "The Clipperton Island Case". The American Journal of International Law. 27 (1): 130–133. doi:10.2307/2189797. JSTOR 2189797.

- "Affaire de l'île de Clipperton (Mexique contre France)" [Case of Clipperton Island (Mexico v. France)] (PDF). Recueil des Sentences Arbitrales [Reports of International Arbitral Awards] (in French). II. United Nations (published 2006). 28 January 1931. pp. 1105–1111.

- John P. Grant; J. Craig Barker, eds. (2009). "Clipperton Island Case". Encyclopaedic Dictionary of International Law (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195389777.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-538977-7.

- William B. Heflin (2000). "Diayou/Senkaku Islands Dispute: Japan and China, Oceans Apart" (PDF). Asian-Pacific Law & Policy Journal. 1 (18): 11–13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2010. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- "About Clipperton Island". The Clipperton Project. 2014. Archived from the original on 17 January 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- Elaine Jobin. "Trip Report and Photos: Clipperton Island – April 10–25, 2010". ElaineJobin.com. Archived from the original on 27 April 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- "Added by @simonagerphotography Instagram post Photo by @simonagerphotography // On campaign with @seashepherdsscs The @mvbrigittebardot drifting in front of Clipperton Island. The British Pacific Island Company acquired the rights to guano deposits in 1906 and built a mining settlement in conjunction with the Mexican government. That same year, a lighthouse was erected under the orders of President Porfirio Díaz. By 1914 around 100 people—men, women, and children—were living there, resupplied every two months by a ship from Acapulco. With the escalation of fighting in the Mexican Revolution, the regular resupply visits ceased and the inhabitants were left to their own devices. By 1917 all but one of the male inhabitants had died. Many had perished from scurvy, while others (including Captain Arnaud) died during an attempt to sail after a passing ship to fetch help. Lighthouse keeper Victoriano Álvarez was the last man on the island, together with 15 women and children. Álvarez proclaimed himself "king" and began an orgy of rape and murder, before being killed by Tirza Rendon, who was the recipient of his unwanted attention. Almost immediately after Álvarez's death four women and seven children, the last survivors, were picked up by the US Navy gunship Yorktown on 18 July 1917. No more attempts were made to colonize it, though it was briefly occupied during the 1930s and 1940s. The island is now home to hundreds of thousands of boobie and frigate birds. #clippertonisland #mvbrigittebardot #seashepherd #island #birdsanctuary #dji #drone #adventure #natgeotraveller #sealegacy #turningthetide #seashepherd #clipperton #clippertonisland - Picuki.com". www.picuki.com. Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- "Added by @simonagerphotography Instagram post Photo by @simonagerphotography // On campaign with @seashepherdsscs The @mvbrigittebardot drifting in front of Clipperton Island. The British Pacific Island Company acquired the rights to guano deposits in 1906 and built a mining settlement in conjunction with the Mexican government. That same year, a lighthouse was erected under the orders of President Porfirio Díaz. By 1914 around 100 people—men, women, and children—were living there, resupplied every two months by a ship from Acapulco. With the escalation of fighting in the Mexican Revolution, the regular resupply visits ceased and the inhabitants were left to their own devices. By 1917 all but one of the male inhabitants had died. Many had perished from scurvy, while others (including Captain Arnaud) died during an attempt to sail after a passing ship to fetch help. Lighthouse keeper Victoriano Álvarez was the last man on the island, together with 15 women and children. Álvarez proclaimed himself "king" and began an orgy of rape and murder, before being killed by Tirza Rendon, who was the recipient of his unwanted attention. Almost immediately after Álvarez's death four women and seven children, the last survivors, were picked up by the US Navy gunship Yorktown on 18 July 1917. No more attempts were made to colonize it, though it was briefly occupied during the 1930s and 1940s. The island is now home to hundreds of thousands of boobie and frigate birds. #clippertonisland #mvbrigittebardot #seashepherd #island #birdsanctuary #dji #drone #adventure #natgeotraveller #sealegacy #turningthetide #seashepherd #clipperton #clippertonisland - Picuki.com". www.picuki.com. Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- Mansmann, Ivo (1990). Clipperton: Schicksale auf einer vergessenen Insel: Roman [Clipperton: Destinies on a forgotten island: A novel] (in German). Halle: Mitteldeutscher Verlag. ISBN 978-3-35-400709-3. OCLC 31495383.

- Restrepo, Laura (1989). La Isla de la Pasión [Passion Island] (in Spanish). Bogotá, Colombia: Planeta. ISBN 978-0-06-081620-9. OCLC 21335043.

- Bergua, Ana Garcia (2007). Isla de Bobos [Booby Island] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Planeta Editorial. ISBN 978-9-70-749064-2. OCLC 180756453.

- Simon Rogerson (19 July 2006). "Cousteau and the Pit". Dive magazine. Archived from the original on 15 April 2009.

- Arias, Ron (1990). Five against the sea: A true story of courage and survival. Viking. ISBN 978-0-67-083092-3.

- LaJoie, John. American Maritime Accident Report, 1998

- C. Jost (2014). "Bienvenue sur l'île de La Passion ... Clipperton!" [Welcome to Passion Island ... Clipperton!] (in French). Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- "Lance Milbrand". Milbrand Cinema. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- Nelson, Dan; Sachs, Julian (2 April 2008). "Clipperton Atoll Expedition – 2008". Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- Ben Cahoon. "French Minor Dependencies". World Statesmen.org.

- "Re: Probe into Sichem Osprey grounding". Diver.net. 1 March 2010. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- "Xylene Tanker Runs Aground on Clipperton Island". Reeftools. 22 February 2010. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- "Eitzen tanker Sichem Osprey refloated". Lloydslist.com. 8 March 2010. Archived from the original on 12 January 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- "Sichem Osprey". MarineTraffic. 13 June 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- "Plastic Surveying and Collection". The Clipperton Project. 12 March 2012. Archived from the original on 2 May 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- "Clipperton Island". TX5K.org. The 2013 Cordell Expedition.

- Schmieder, Robert W. (15 June 2013). "Report of the Expedition Leader" (PDF). cordell.org. The 2013 Cordell Expedition to Clipperton Island. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

Sources

- Allen, G.R.; Robertson, D.R. (1996). "An annotated checklist of the fishes of Clipperton Atoll, tropical eastern Pacific".

- Dickinson, Edwin D. "The Clipperton Island case". American Journal of International Law. 27 (1): 130–133.

- "State of Coral Reefs in Clipperton Island". French Coral Reef Initiative (IFRECOR). 1998. Retrieved 11 January 2018 – via ReefBase. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Jost, C.; Andrefouët, S. (2006). "Review of long term natural and human perturbations and current status of Clipperton Atoll, a remote island of the Eastern Pacific". Pacific Conservation Biology. 12. Chipping Norton, NSW, Australia: Surrey Beatty & Sons Pty. Ltd. p. 3.

- Jost, C. (1 July 2005). "Risques environnementaux et enjeux à Clipperton (Pacifique français)". Revue européenne Cybergeo (in French). 314. Archived from the original on 21 November 2003.

cartes et fig., 15 p.

- Jost, C. (June–December 2005). "Bibliographie de l'île de Clipperton, île de La Passion (1711–2005)". Journal de la Société des Océanistes (in French). Paris, FR. 120–121: 181–197.

texte et 411 réf.

CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Pitman, R.L.; Jehl, J.R. (1998). "Geographic variation and reassessment of species limits in the "masked" boobies of the eastern Pacific Ocean". Wilson Bulletin. 110: 155–170.

- Sachet, M.H. (7 March 1962). "Flora and vegetation of Clipperton Island". Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences. 4th. San Francisco: The California Academy of Sciences. 31 (10): 249–307. Retrieved 12 January 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Skaggs, Jimmy (1989). Clipperton. A history of the island the world forgot. New York, NY: Walker and Company.

- Snodgrass, R. E. & Heller, E. (30 September 1902). "The birds of Clipperton and Cocos Islands". Proceedings of the Washington Academy of Sciences. Papers from the Hopkins Stanford Galápagos expedition 1898–1899. IV: 501–520. Retrieved 11 January 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tamburini, Francesco (2008). "La controversia tra Francia e Messico sulla sovranità dell'isola di Clipperton e l'arbitrato di Vittorio Emanuele III (1909–1931)". Ricordo di Alberto Aquarone, Studi di Storia (in Italian). Pisa, IT: Edizioni Plus.

- Central and Western Pacific. UNEP Regional Seas Directories and Bibliographies. Coral Reefs of the World. 3. Gland, Switzerland; Cambridge, UK; Nairobi, Kenya: IUCN/UNEP. 1988.

External links

- (in French) Clipperton.fr Website by C. Jost, CNRS researcher

- Isla Clipperton o "Los náufragos mexicanos -1914/1917-" (in Spanish)

Photo galleries

- The First Dive Trip to Clipperton Island aboard the Nautilus Explorer Pictures were taken during a 2007 visit

- Clipperton Island 2008 Flickr gallery containing 94 large photos from a 2008 visit

- 3D Photos of Clipperton Island 2010 3D anaglyphs

Visits and expeditions

- 2000 DXpedition to Clipperton Island Website of a visit by amateur radio enthusiasts in 2000

- Clipperton Journal Diary of a 2003 visit by Lance Milbrand on NationalGeographic.com

- (in French) Expédition Clipperton Site of the 2005 scientific mission of Jean-Louis Étienne

- Clipperton Atoll Expedition 2008 Pages of the 2008 expedition by the School of Oceanography, University of Washington

- 2013 Cordell expedition Website of another visit by amateur radio enthusiasts

- Diving trips to Clipperton atoll