Charles K. Bliss

Charles K. Bliss (September 5, 1897–1985) was a chemical engineer and semiotician, best known as the inventor of Blissymbols, an ideographic writing system. He was born in the Austro-Hungarian Empire but immigrated to Australia after the Second World War and The Holocaust.

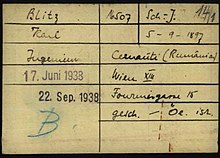

Charles K. Bliss | |

|---|---|

| Born | Karl Kasiel Blitz September 5, 1897 |

| Died | 1985 |

| Citizenship | Ukraine Australia |

| Alma mater | Vienna University of Technology |

| Occupation | chemical engineer, semiotician |

| Known for | Inventor of Blissymbolics |

Early life

Bliss was born Karl Kasiel Blitz, the eldest of four children to Michel Anchel and Jeanette Blitz, in Chernivtsi in the Austro-Hungarian Empire (current Ukraine). The family were impoverished and the senior Blitz supported the family as an optician, mechanic, and wood turner.

Later on Bliss said that the symbols on his father's circuit diagrams made instant sense to him. They were a "logical language". He was similarly impressed by chemical symbols, which he thought could be read by anyone, regardless of their mother tongue.

Bliss's early life was difficult. It was cold and his family were poor and hungry. Because the family was Jewish, he suffered anti-Semitic taunts.

When Bliss was eight years old, Russia lost the Russo-Japanese War, Russian pogroms against the Jews accelerated, and refugees came into Bliss's town from the nearby Russian town of Kishinev. Also in 1905 Bliss saw a slide show of the Austro-Hungarian North Pole Expedition of Weyprecht and Payer. It inspired him to study engineering to improve technology for ordinary people.

In 1914 Bliss entered World War I, first as a helper with the Red Cross field ambulance, then as an army soldier.[1] After the war he entered university. He graduated from the Vienna University of Technology as a chemical engineer in 1922. He joined Telefunken, a German television and radio apparatus company, and rose to be chief of the patent department.

Detention and Second World War

In March 1938, the Third Reich annexed Austria via the Anschluss, and Bliss, as a Jew, was sent to Dachau concentration camp. Later. he was moved to Buchenwald concentration camp. His wife, Claire, a German Catholic, made constant efforts to have him released. He was released in 1939 but was required to leave the country for England immediately. In England, Bliss tried to bring his wife to him, but the outbreak of World War II in September 1939 made that impossible. It was there that, because the Nazi bombing of England was called the "blitz," he changed his surname to Bliss.

Bliss arranged for Claire to escape Germany via his family in Cernăuți, Romania (now called Chernivtsi in present day Ukraine). Needing to leave there, Claire moved on to Greece and safety, until October 1940 when Italy invaded Greece. The couple were reunited on Christmas Eve 1940, after Claire continued east to Shanghai and Charles went west to Shanghai via Canada and Japan.

After the Japanese occupied Shanghai, Bliss and his wife were placed into the Hongkew ghetto. Claire, as a German and a Christian had the option of claiming her German citizenship, applying for a divorce and being released. She did not do so and instead accompanied Bliss into the ghetto.

Development of symbolic writing system

In Shanghai, Bliss became interested in Chinese characters, which he mistakenly thought were ideograms. He studied them and learned how to read shop signs and Chinese newspapers. With some astonishment, he one day realised that he had been reading the symbols off not in Chinese, but in his own language, German. With ideograms for his inspiration, Bliss set out to develop a system of writing by pictures. At that time Bliss had not become aware of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz's "Universal Symbolism".

Bliss and his wife migrated to Australia after the war, reaching Australia in July 1946. His semiotic ideas met with universal rejection. Bliss, without any Australian or Commonwealth qualifications, had to work as a labourer to support his family. He worked on his system of symbols at night. Bliss and his wife became Australian citizens.

Originally Bliss had called his system "World Writing" because the aim was to establish a series of symbols that would be understood by all, regardless of language. Bliss then decided an English-language name was too restricted and called the system Semantography. In Sydney in 1949 Bliss published the three-volume International Semantography: A non-alphabetical Symbol Writing readable in all languages. There was no great positive reaction. For the next four years Claire Bliss sent 6,000 letters to educators and universities, to no better effect.

Bliss's wife died in 1961 after years of ill health.

In 1965 Bliss published a second edition of his work, Semantography (Blissymbolics).

It was about this time that the increase in international tourism convinced many that only a pictorial symbol language could be understood by all. Bliss made sure his idea was attached to his name, hence Blissymbolics.

Educational use

In 1971, Bliss learned that since 1965, the Ontario Crippled Children's Centre in Toronto, Canada (now Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital) had been using his symbols to teach children with cerebral palsy to communicate. He was thrilled at first and traveled to Canada, but he became horrified when he learned that the center had extended his set of symbols and was using the symbols as a bridge to help the children learn to use spoken and written words in a traditional language, which were far from his vision for Blissymbolics. He badgered and eventually sued the center, at one time even threatening a nurse with imprisonment. After ten years of constant attacks from Bliss, the center came to a compromise with Bliss because it felt the publicity he drew to be bringing a bad name to the center. The world copyright for use of his symbols with handicapped children was licensed to the Blissymbolics Communication Foundation in Canada.

Recognition

Bliss was the subject of the 1974 film Mr Symbol Man, a co-production of Film Australia and the National Film Board of Canada.[2]

Bliss was made a Member of the Order of Australia (A.M.) in 1976 for "services to the community, particularly to handicapped children".[3]

On the basis of the recognition of the innovative nature of his work, Bliss was appointed an Honorary Fellow in Linguistics at the Australian National University, by the (then) Head of the ANU School of Linguistics, Professor Bob Dixon, in 1979.[2]

See also

Footnotes

- "Semantography Blissymbolics:: Timeline of Charles Bliss' Life". www.semantography-blissymbolics.com. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- 'Symbol Man' an ANU Fellow, The Canberra Times, (Thursday, 29 March 1979), p.10.

- Awards in Order of Australia, The Canberra Times, (Saturday, 12 June 1976)< p8.

Publications

Bliss

- Bliss, C.K., International Semantography: A Non-Alphabetical Symbol Writing Readable in All Languages. A Practical Tool for General International Communication, Especially in Science, Industry, Commerce, Traffic, etc. and for Semantical Education, Based on the Principles of Ideographic Writing and Chemical Symbolism, Institute of Semantography, (Sydney), 1949.

- Bliss, C.K., Semantography-Blissymbolics: A Simple System of 100 Logical Pictorial Symbols, Which can be Operated and Read Like 1+2=3 in All Languages... (Third, Enlarged Edition), Semantography-Blissymbolics Pubs, (Sydney), 1978.

- Bliss, C.K., Semantography and the Ultimate Meanings of Mankind: Report and Reflections on a Meeting of the Author with Julian Huxley. A selection of the Semantography Series; with "What scientists think of C.K. Bliss' semantography", Institute for Semantography, (Sydney), 1955.

- Bliss, C.K., The Blissymbols Picture Book (Three Volumes), Development and Advisory Publications of N.S.W. for Semantography-Blissymbols, (Coogee), 1985.

- Bliss, C.K., The Story of the Struggle for Semantography: The Semantography Series, Nos.1–163, Institute for Semantography, (Coogee), 1942–1956.

- Bliss, C.K. & McNaughton, S., Mr Symbol Man: The Book to the Film Produced by the National Film Board of Canada and Film Australia (Second Edition), Semantography (Blissymbolics) Publications, (Sydney), 1976.

- Bliss, C.K. (& Frederick, M.A. illus.), The Invention and Discovery That Will Change Our Lives, Semantography-Blissymbolics Publications, (Sydney), 1970.

Others

- Breckon, C.J., "Symbolism as a Written Language", pp.74–83 in Breckon, C.J., Graphic Symbolism, McGraw-Hill, Sydney), 1975.

- Reiser, O.L., Unified symbolism for world understanding in science: including Bliss symbols (Semantography) and logic, cybernetics and semantics: A paper read in parts at the Annual Meeting of the AmericanAssociation for the Advancement of Science, Philadelphia, 1951, and at the Conference of the InternationalSociety of Significa, Amsterdam, 1953, Semantography Publishing Co., (Coogee), 1955.

External links

- Mr. Symbol Man (1974) on IMDb

- Mr. Bliss, RadioLab Podcast, accessed 24 December 2012

- "Biography of C. K. Bliss"