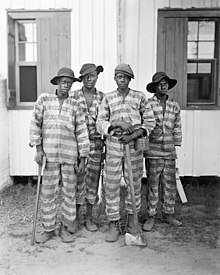

Chain gang

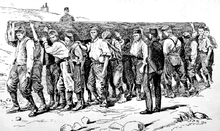

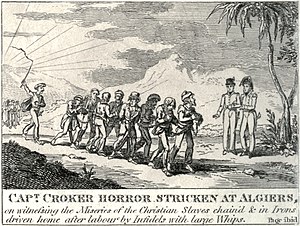

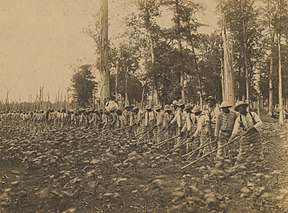

A chain gang is a group of prisoners chained together to perform menial or physically challenging work as a form of punishment.[1] Such punishment might include repairing buildings, building roads, or clearing land.[2] This system existed primarily in the Southern United States, and by 1955 had largely been phased out nationwide, with Georgia among the last states to abandon the practice.[3] North Carolina continued to use chain gangs into the 1970s.[4][5] Chain gangs were reintroduced by a few states during the "get tough on crime" 1990s, with Alabama being the first state to revive them in 1995. The experiment ended after about one year in all states except Arizona,[6] where in Maricopa County inmates can still volunteer for a chain gang to earn credit toward a high school diploma or avoid disciplinary lockdowns for rule infractions.[7] The introduction of chain gangs into the United States began before the American Civil War. The southern states needed finances and public works to be performed. Prisoners were a free way for these works to be achieved.[8]

.jpg)

Synonyms and disambiguation

A single ankle shackle with a short length of chain attached to a heavy ball is known as a ball and chain. It limited prisoner movement and impeded escape.

Two ankle shackles attached to each other by a short length of chain are known as a hobble or as leg irons. These could be chained to a much longer chain with several other prisoners, creating a work crew known as a chain gang. The walk required to avoid tripping while in leg irons is known as the convict shuffle.

A group of prisoners working outside prison walls under close supervision, but without chains, is a work gang. Their distinctive attire (stripe wear or orange vests or jumpsuits) and shaven heads served the purpose of displaying their punishment to the public, as well as making them identifiable if they attempted to escape. However, the public was often brutal, swearing at convicts and even throwing things at them.[9]

The use of chains could be hazardous. Some of the chains used in the Georgia system in the first half of the twentieth century weighed 20 pounds (9 kg). Some prisoners suffered from shackle sores — ulcers where the iron ground against their skin. Gangrene and other infections were serious risks. Falls could imperil several individuals at once.

Modern prisoners are sometimes put into handcuffs or wrist manacles (similar to handcuffs, but with a longer length of chain) and leg irons, with both sets of manacles (wrist and ankle) being chained to a belly chain. This form of restraint is most often used on prisoners expected to be violent, or prisoners appearing in a setting where they may be near the public (a courthouse) or have an opportunity to flee (being transferred from a prison to a court). Although prisoners in these restraints are sometimes chained to one another during transport or other movement, this is not a chain gang — although reporters may refer to it as such — because the restraints make any kind of manual work impossible.

History

Various claims as to the purpose of chain gangs have been offered. These include:

- punishment

- societal restitution for the cost of housing, feeding, and guarding the inmates. The money earned by work performed goes to offset prison expenses by providing a large workforce at no cost for government projects, and at minimal convict leasing cost for private businesses

- a way of perpetuating African-American servitude after the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution ended slavery outside of the context of punishment for a crime.[10]

- reducing inmates' idleness

- to serve as a deterrent to crime

- to satisfy the needs of politicians to appear "tough on crime"

- to accomplish undesirable and difficult tasks

The use of chain gangs for prison labor was the preferred method of punishment in some southern states like Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Virginia, North Carolina, Arkansas, Texas, Mississippi, and Alabama.[11]

The use of chain gangs in the United States generally ended in 1955.

Chain gangs experienced a resurgence when Alabama began to use them again in 1995.[10]

Reintroduction

Several jurisdictions in the United States have re-introduced prison labor. In 1995 Sheriff Joe Arpaio reintroduced chain gangs in Arizona.

A year after reintroducing the chain gang in 1995, Alabama was forced to again abandon the practice pending a lawsuit from, among other organizations, the Southern Poverty Law Center. "They realized that chaining them together was inefficient; that it was unsafe", said attorney Richard Cohen of the organization. However, as late as 2000, Alabama Prison Commissioner Ron Jones has again proposed reintroducing the chain gang. The 1995 reintroduction has been called "commercial slavery" by some.

Tim Hudak, former leader of the Progressive Conservative Party of Ontario in Canada, campaigned on introducing penal labor in the province, referred to by many as chain gangs.[12] He lost seats to the provincial Liberals which formed another majority government in the subsequent general election.

In popular media

- I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang is an award-winning movie released in 1932, which depicted the degrading and inhumane treatment on chain gangs in the post–World War I era.

- Sullivan's Travels places the protagonist in a chain gang for several scenes.

- The 1950 Chain Gang starred Douglas Kennedy as a reporter working as a guard to expose corruption and brutality.[13]

- Cool Hand Luke stars Paul Newman as a rebellious convict in a chain gang.

- In Disney's Robin Hood, upon King Richard's return to England, all of the film's villains are punished by being made to work on the "Royal Rock Pile" in a chain gang.

- O Brother, Where Art Thou? begins with the protagonists escaping from a chain gang.

- Life, starring Eddie Murphy and Martin Lawrence, features them working on a chain gang.

- In Take the Money and Run, Woody Allen's 1969 mockumentary, his character is in a chain gang.

- The episode "Unchained" of the television series Quantum Leap features protagonist Sam Beckett leaping into a chain gang to help a fellow prisoner escape.

- The song "Work Song" by singer Nina Simone tells the story of working in a chain gang after stealing food out of hunger.

- In Les Misérables by Victor Hugo, the character Jean Valjean is part of a chain gang as part of his punishment for stealing bread.

- Circa 1947, Woody Guthrie, Alec Seward, and Sonny Terry recorded several chain gang related songs including "Chain Gang Special", and several other older songs adapted to having chain gang themes. They were released on the Cleopatra compilation Best Of The War Years. Guthrie had also previously written other chain gang songs, including "Chain Around My Leg", which was released on the Library of Congress Recordings.

- Soul singer Sam Cooke recorded a hit song in 1960 called "Chain Gang". It was written by Cooke and his brother, Charles, after seeing an actual chain gang on a highway.

- Other songs entitled "Chain Gang" have been written and performed by Johnny Cash; Bobby Scott in the 1950s; and as a B-side song to The Blue Hearts' single "Kiss Shite Hoshii".

- "Back on the Chain Gang" is a popular song from the Pretenders album Learning to Crawl.

- "Chain Gang Blues" is the B-side song of Champion Jack Dupree's first single "Warehouse Man Blues", recorded in 1940.

- "No More Chain Gang" - Song by Boney M

- "Livin' On a Chain Gang" is a song by Skid Row.

- Chain gangs are referenced in the AC/DC song "Jailbreak" and in the Red Hot Chili Peppers song "Dani California".

- In the fifth season of Boardwalk Empire, Chalky White is in a chain gang for the first episode.

- In Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison, the main character is given a piece of a chain from Brother Tarp, who was in a chain gang for nineteen years.

- In Toni Morrison's novel Beloved, the character Paul D is forced to work in a chain gang while serving time for attempting to murder his master.

See also

Footnotes

- "Definition of CHAIN GANG". Merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2019-02-21.

- "Chain Gangs". Credo Reference. Retrieved 3 October 2013.

- Roth, Mitchel P (2006). Prisons and prison systems. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-0-313-32856-5.

- "North Carolina: Voices from the Chain Gang | States of Incarceration". Statesofincarceration.org.

- Wooten, James T. (October 23, 1971). "Prison Road Gangs Fading Fast in South". The New York Times.

- Banks, Cyndi (2005). Punishment in America: a reference handbook. ABC-CLIO. pp. 154–156. ISBN 978-1-85109-676-3.

- "Anderson Cooper 360 transcript". CNN. March 10, 2004. Retrieved 2009-06-07.

- Wallenstein, Peter. "Chain Gangs". Credo Reference. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- McShane, Marilyn D. (1996). Encyclopedia of American Prisons. Garland Publishing Inc. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-8153-1350-2.

- Gorman, Tessa M. (March 1997). "Back on the Chain Gang: Why the Eighth Amendment and the History of Slavery Proscribe the Resurgence of Chain Gangs". California Law Review. 85 (2): 441–478. doi:10.2307/3481074. JSTOR 3481074.

- McShane, Marilyn D. (1996). The Encyclopedia of American Prisons. Garland Publishing Inc. pp. 71–73. ISBN 978-0-8153-1350-2.

- Benzie, Robert (July 18, 2011). "Hudak's chain-gang proposal is a danger to public, Liberals warn". Toronto Star. Retrieved August 3, 2011.

- Chain Gang (1950) Turner Classic Movies, Tcm.com

Further reading

- Burns, Robert E. I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang! University of Georgia Press; Brown Thrasher Ed edition (October 1997; original copyright, late 1920s).

- Childs, Dennis. Slaves of the State: Black Incarceration from the Chain Gang to the Penitentiary. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2015.

- Colvin, Mark. Penitentiaries, Reformatories, and Chain Gangs: Social Theory and the History of Punishment in Nineteenth-Century America. Palgrave Macmillan (2000). ISBN 0-312-22128-2.

- Curtin, Mary Ellen. Black Prisoners and Their World : Alabama, 1865–1900. University of Virginia Press (2000).

- Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Vintage Books (1979). ISBN 0-394-72767-3.

- Lichtenstein, Alex. Twice the Work of Free Labor: The Political Economy of Convict Labor in the New South. Verso (1995). ISBN 1-85984-086-8.

- Mancini, Matthew J. One Dies, Get Another: Convict Leasing in the American South, 1866–1928. University of South Carolina Press (1996). ISBN 1-57003-083-9.

- Oshinsky, David M. Worse than Slavery: Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice. (1997). ISBN 0-684-83095-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chain gangs. |