Cawdor (Roman fort)

Easter Glacantray, an alleged Roman fort), is located near the small village of Cawdor (15 miles east of Inverness). It is alleged to be a Roman fort although there is a lack of archaeological evidence to support this claim.[1]

Discovery

In 1984, the site of an alleged Roman fort was identified at Easter Galcantray, south west of Cawdor, by aerial photography.[2]

The site was excavated between 1985 and 1990 with a single fragment of pottery being discovered which was assumed to be Roman because it looked similar to a fragment found at Inchtuthil legionary fortress. Other features alleged to be Roman, are just as likely to belong to structures built in other periods. The most recent analysis of the site can be found in [3].

Jones (1986a) interpreted the main structural phase within the (Cawdor) site’s history as potential evidence for the presence of a Roman military work. This assumption was based on a number of salient factors. These include: the rectilinear form of the enclosure ditch, with its V-shaped profile; Postholes were uncovered which Jones assumed belonged to a gate, although tis was an assumption that four postholes made a gate - these postholes are not evenly spread and are unlikely to have all been part of the same structure. Jones also noted the presence of possible contemporary rectilinear timber buildings, which he thought were reminiscent in both size and form to barrack blocks, although the reality is that Jones was, again, 'joining the dots' and assuming that the postholes, which were not equally spread, are from the same structure; and finally, the dating evidence.[4] This, based on the one sigma calibrated range, suggests the slighting of the site during the late first century AD, which would correspond to the governorship of Agricola, or possibly his unknown successor.[5]

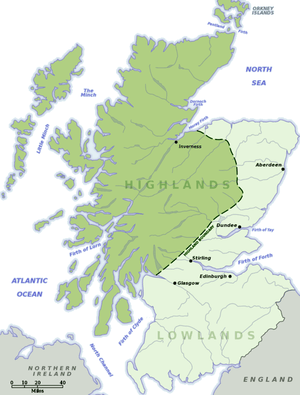

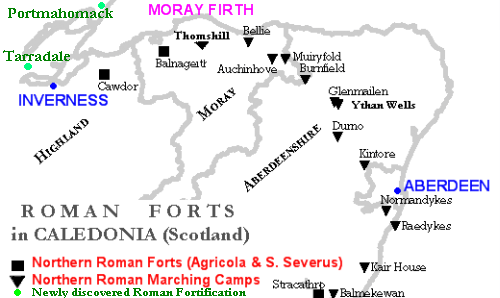

If confirmed, it would be the most northerly known Roman fort in the British Isles, but this is highly unlikely given that the next nearest fort is Stracathro, over 100 miles away.[6] It is not confirmed that Agricola reached this far north, despite misleading discoveries at Portmahomack[7] and Tarradale on the northern shores of the Beauly Firth,[8] but archaeologists who specialise in the Roman period have been consistently reticent in confirming Jones' interpretation of the site.[9]

More research required

Easter Galcantray is near Inverness, and has never seriously been considered the northernmost place of Roman conquest, despite what amateur historians and conspiracy theorists say.

Historically it is known that in the summer of 83AD Agricola defeated the massed armies of the Caledonians, led by Calgacus, at the Battle of Mons Graupius. With victory, Agricola extracted hostages from the Caledonian tribes and instructed his fleet to sail around the north coast confirming to the Romans the province of Britannia was an island.

Agricola then may have marched his army to the northern coast of Britain,[10] and reached the Inverness area, in the vicinity of the Easter Galcantray (Cawdor) Fort. In 1985, it was recorded that a "small piece of Roman coarse ware“ was found with burnt material at the bottom of a ditch at the site[11] but subsequent studies of the pottery identified it as medieval.[12]

Similarly, although radiocarbon tests of material recovered from the site gave possible dates of construction during the first century,[13] its interpretation remains problematic because the site was occupied and abandoned quite quickly leaving no other evidence.[14] Furthermore, there has been no academic consensus over two centuries regarding the actual location for the battle of Mons Graupius. For example, William Roy (1793),[15] Gabriel Jacques Surenne (1823),[16] Archibald Watt[17] and C. Michael Hogan[18] believe it was fought further south on the coast near the Roman camps of Raedykes[19] or Glenmailen.[20] Whereas Vittorio di Martino (author of "Roman Ireland", about a possible Roman expedition to Ireland) believes the Roman victory happened in an area southwest of Cawdor.[21]

See also

Notes

- Roman Fort discovery at Cawdor/Easter Galcantray

- G.D.B. Jones & I. Keillor, "Easter Galcantray", Discovery & Excavation Scotland 1984 (1984), p. 14: "On south bank of river Nairn, straight cropmark with gap in middle and suggestion of two more sides, truncated by river, at right angles to main mark."

- A Tibbs, Beyond the Empire: A Guide to the Roman Remains in Scotland (2019), p. 190.

- A single radiocarbon date of 1880 +/- 20 BP, obtained from a layer of charcoal in the re-cut western ditch.

- R.A. Gregory, "Excavations by the late G.D.B. Jones and C.M. Daniels along the Moray Firth littoral", Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 131 (2001), pp. 177-222 , at p.204.

- Roman fort near Inverness Archived June 14, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- RCAHMS: Port A'Chaistell

- Google Book: Tarradale, a possible roman camp. p. 176

- G.S. Maxwell & D.R. Wilson, "Aerial reconnaissance in Roman Britain 1977-84", Britannia Vol. 18 (1987), pp. 1-48, at p. 34: "For the present, it may be noted that, viewed as crop-mark sites, neither [Cawdor nor Thomshill] sits happily in the established morphological categories of standard Roman military installations in North Britain". D.J. Breeze, "Why did the Romans fail to conquer Scotland?", Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 118 (1988), pp. 3-22, at p. 8: "the suggested Roman context for the sites at Easter Galcantray [Cawdor] and Thoms Hill - Daniels 1986 and Jones 1986 - fails to convince; most of the evidence from the former site would better sit within a medieval context ..."

- Wolfson, Stan (2002). "THE BORESTI : THE CREATION OF A MYTH In the manuscript of Agricola". 38 (2).

In finis Borestorum exercitum deducit - He led his army down into the territory of the Boresti" may be emended to: in finis boreos totum exercitum deducit - "He led his entire army down into the northern extremities

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Jones, G.D.B. & Keillor, I (1985). "Easter Galcantray". Discovery & Excavation Scotland: 27.

- Gregory, R.A. (2001). "Excavations by the late G.D.B. Jones and C.M. Daniels along the Moray Firth littoral". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 131: 177–222.

This sherd of pottery was subsequently dated to 1300±140 AD (Dur87TL-2AS) by thermoluminescence

- "Excavations at Cawdor 1986" (PDF). www.her.highland.gov.uk. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- Gregory, R.A. (2001). "Excavations by the late G.D.B. Jones and C.M. Daniels along the Moray Firth littoral". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 131: 34.

Likewise, the single calibrated radiocarbon date retrieved from the ‘demolition deposit’ within the ditch, although partially spanning the Flavian period at both one and two sigma standard deviations (cal AD 80–130 (1 sigma): cal AD 80–220 (2 sigma) ), remains problematic. It is not, in itself, conclusive evidence that the site was occupied and abandoned during the late first century AD. Still less is it conclusive evidence that it was occupied and abandoned by the Roman military, particularly since no late first-century Roman pottery was recovered from this feature or from elsewhere on the site.

- Roy, William (1793). The Military Antiquities of the Romans in Britain.

- Surenne, Gabriel Jacques (1823). Correspondence to Sir Walter Scott.

- Watt, Archibald. Highways and byways around Kincardineshire. Stonehaven Heritage Soc., Scotland.

- Hogan, C. Michael. "Elsick Mounth". The Megalithic Portal.

- "Raedykes". www.canmore.rcahms.gov.uk. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- "Glenmaillen: Roman Camps of Agricola and Septimius Severus". www.canmore.rcahms.gov.uk. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- Di Martino, Vittorio (2006). Roman Ireland. The Collins Press. p. 14.

Bibliography

- Di Martino, Vittorio. Roman Ireland. The Collins Press. London, 2003.

- Jones and Keillar. Excavations at Cawdor. University of Manchester, 1986

- Hanson, William S. "The Roman Presence: Brief Interludes", in Edwards, Kevin J. & Ralston, Ian B.M. (Eds) (2003) Scotland After the Ice Age: Environment, Archaeology and History, 8000 BC - AD 1000. Edinburgh. Edinburgh University Press.

- Hanson, William S. Roman campaigns north of the Forth-Clyde isthmus: the evidence of the temporary camps, Proc Soc Antiq Scot, vol.109 142, 145 Edinburgh, 1980.

- Macdonald, G (1916) The Roman camps at Raedykes and Glenmailen, Proc Soc Antiq Scot, vol.50 348-359

- Maxwell, G S (1980) Agricola's campaigns: the evidence of the temporary camps, Scot Archaeol Forum, vol.12 34, 35, 40, 41

- Moffat, Alistair (2005) Before Scotland: The Story of Scotland Before History. London. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05133-X

- Pitts, L. Inchtuthil. The Roman Legionary Fortress. Britannia Monograph Series 6 (1985)

- Robertson, A S (1976) Agricola's campaigns in Scotland, and their aftermath, Scot Archaeol Forum, vol.7 4

- St Joseph, J K (1951) Air reconnaissance of North Britain, J Roman Stud, vol.41 65

- Tibbs, A. Beyond the Empire: A Guide to the Roman Remains in Scotland, (Crowood Press 2019)

- Woolliscroft,D. and Hoffmann,B. The First Frontier. Rome in the North of Scotland (Stroud: Tempus 2006)

External links

- Excavations of Jones and Daniels

- RCAHMS: Cawdor Roman Fort excavations at Easter Galcantray

- The Roman Gask Project

- Temporary Marching Camp: Normandykes, Peterculter, Grampian (2004)

- Britannia - The Roman army and navy in Britain (55BC - 410AD)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nairnshire. |