CSX 8888 incident

The CSX 8888 incident, also known as the Crazy Eights incident, was a runaway train event involving a CSX Transportation freight train in the U.S. state of Ohio on May 15, 2001. Locomotive #8888, an EMD SD40-2, was pulling a train of 47 cars including some loaded with hazardous chemicals, and ran uncontrolled for two hours at up to 82 kilometers per hour (51 mph).[2] It was finally halted by a railroad crew in a second locomotive, which caught the runaway and coupled to the rear car.[3]

| CSX 8888 incident | |||

|---|---|---|---|

A CSX SD40-2 locomotive, similar to the locomotive involved in the incident. | |||

| Details | |||

| Date | May 15, 2001 12:35 p.m.[1] | ||

| Location | Walbridge – Kenton, Ohio 106 km (66 mi) S | ||

| Country | United States | ||

| Operator | CSX Transportation | ||

| Incident type | Runaway train | ||

| Cause | Operator error | ||

| Statistics | |||

| Trains | CSX freight train | ||

| Passengers | 0 | ||

| Crew | 1 (0 for majority) | ||

| Deaths | 0 | ||

| Injured | 1 | ||

| |||

As of 2018, #8888 is still in service, having been rebuilt and upgraded into a SD40-3 as part of a refurbishment program carried out by CSX, although its number is now #4389.[4] It previously operated as Conrail #6410, being delivered to the railroad in September 1977.

Timeline

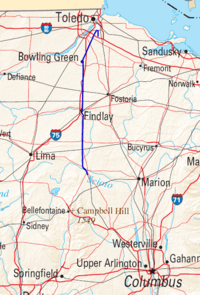

On May 15, 2001, a CSX locomotive engineer was using Locomotive #8888 to move a string of freight cars from one track to another within Stanley Yard in Walbridge, Ohio, CSX's primary classification yard for Toledo.[2] The string consisted of 47 freight cars, 22 of which were loaded. Two tank cars contained thousands of gallons of molten phenol, a toxic ingredient of paints, glues, and dyes that is harmful when it is inhaled, ingested, or comes into contact with the skin.

The engineer, a 35-year veteran (whose name has not been disclosed) with a clean disciplinary record, noticed a misaligned switch and concluded that his train, although moving slowly, would not be able to stop short of it. He decided to climb down from the train, correctly align the switch, and reboard the locomotive.

Before leaving the cab, the engineer applied the locomotive's independent air brake. During mainline operation, he would also have applied the automatic air brake, setting the brakes in each of the train's cars. But, as is normal for intra-yard movements, the air brakes of the train were disconnected from the locomotive, and thus were not functional. Furthermore, applying the locomotive's brakes disabled the train's dead man's switch, which would otherwise have applied the train brakes and cut the engine power.

The engineer also attempted to apply the locomotive's dynamic brake to slow the train to a crawl; dynamic brakes dissipate momentum (kinetic energy) by using the momentum of the train to drive the main generator, generating electricity, exactly like a regenerative braking system in a hybrid automobile, which slows the train. In effect this is very much like using engine braking in a car or exhaust/"jake" brakes in a tractor truck (even up to increasing the revs of the engine thereby making it harder for the engineer to discern whether the throttle was successfully placed into "full brake" or "full throttle", as it turned out); however in this case the braking effect is totally unrelated to the engine itself. However, the engineer "inadvertently failed to complete the selection process", meaning that the train's engine was set to accelerate, not to brake. He then set the throttle for the traction motors at notch 8. If the dynamic brakes had been engaged as intended, this throttle setting would have used the motors against the momentum of the train, causing it to slow down. Instead the train began to accelerate. Therefore, the only functioning brake was the air brake on the locomotive, and this was not enough to counteract its engine power.[1]

The engineer climbed down from the cab, aligned the switch, and then attempted to reboard the accelerating locomotive. But he was unable to do so and was dragged about 24 meters (80 ft), receiving minor cuts and abrasions. There were no other injuries or deaths resulting from the incident. The train rolled out of the yard and began a 105-kilometer (65 mi) journey south through northwest Ohio with no one at the controls.

Attempts to derail the train using a portable derailer failed. Police also shot at an emergency fuel cutoff switch, which had no effect because the button must be pressed for several seconds before the engine is starved of fuel and shuts down. A northbound freight train, Q636-15, was directed onto a siding where the crew uncoupled its locomotive, #8392 (another EMD SD40-2), and waited for the runaway train to pass. #8392 had a crew of two: Jess Knowlton, an engineer with 31 years of service; and Terry L. Forson, a conductor with one year's experience.[5] Together, they chased the runaway train. An EMD GP40-2, CSX locomotive #6008, was prepared further down the line to couple to the front of the runaway to slow it further, if necessary.

Knowlton and Forson successfully coupled onto the rear car, and slowed the train by applying the dynamic brakes on the chase locomotive. Once the runaway had slowed to 18 kilometers per hour (11 mph), CSX trainmaster Jon Hosfeld ran alongside the train, climbed aboard, and shut down the engine. The train was stopped just southeast of Kenton, Ohio, before reaching the GP40-2.[1] All the brake shoes on #8888 had been destroyed by the heat from being applied throughout the runaway trip.

Preservation attempts

Several railway museums had tried to buy #8888, but CSX officials replied that they did not feel the locomotive was worthy of preservation, and that it would be rebuilt as part of the SD40-3 rebuild program in late 2014 and early 2015. The locomotive now operates as CSX SD40-3 #4389.[4]

In film

The incident inspired the 2010 movie Unstoppable.[6]

References

- Kohlin, Ron. "CSX 8888 Runaway Investigation". Kohlin.com. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- "Station: Stanley Yard, Ohio". Michigan's Internet Railroad History Museum. Archived from the original on 2015-11-01. Retrieved December 17, 2015.

- "Runaway train stopped after uncontrolled 2 hours". CNN. May 16, 2001. Archived from the original on February 11, 2006. Retrieved February 24, 2007.

- Lambert, Jason (2016-06-01). "Canadian Railway Observations: South of the Border". canadianrailwayobservations.com. Retrieved 2018-08-16.

- Worden, Amy (November 12, 2010). "Pennsylvania man lived the drama that inspired 'Unstoppable'". The Philadelphia Inquirer.

- David Patch (November 12, 2010). "At times, 'Unstoppable' goes off track from reality". Toledo Blade.