Bushido

Bushidō (武士道, "the way of warriors") was the set of codes of honour and ideals that dictated the samurai way of life,[1] loosely analogous to the European concept of chivalry.[2]

The "way" originates from the samurai moral values, most commonly stressing some combination of sincerity, frugality, loyalty, martial arts mastery, and honour until death. Born from Neo-Confucianism during times of peace in the Edo period (1603–1867) and following Confucian texts, while also being influenced by Shinto and Zen Buddhism, allowing the violent existence of the samurai to be tempered by wisdom, patience and serenity. Bushidō developed between the 16th and 20th centuries, debated by pundits who believed they were building on a legacy dating back to the 10th century, although the term bushidō itself is "rarely attested in pre-modern literature".[3] This ethical code took shape with the rise of the warrior caste to power (end of the Heian period, 794–1185) and the establishment of the first military government (shogunate) of the Kamakura period (1185–1333), the Muromachi period (1336–1573) and formally defined and applied in law by Tokugawa shogunates in the Edo period (1603–1868).[4][5] There is no strict definition, and even if the times are the same, the interpretation varies greatly depending on the person.[6] Bushido has undergone many changes throughout Japanese history, and various samurai clans interpreted it in their own way.

The word bushidō was first used in Japan during the 17th century in Kōyō Gunkan,[7][8][9] but did not come into common usage until after the 1899 publication of Nitobe Inazō's Bushido: The Soul of Japan.[10] In Bushido (1899), Nitobe wrote:

Bushidō, then, is the code of moral principles which the samurai were required or instructed to observe ... More frequently it is a code unuttered and unwritten ... It was an organic growth of decades and centuries of military career. In order to become a samurai this code has to be mastered.[11]

Nitobe was the first to document Japanese chivalry in this way. In Feudal and Modern Japan (1896), historian Arthur May Knapp wrote:

The samurai of thirty years ago had behind him a thousand years of training in the law of honor, obedience, duty, and self-sacrifice ... It was not needed to create or establish them. As a child he had but to be instructed, as indeed he was from his earliest years, in the etiquette of self-immolation.[12]

Etymology

Bushidō (武士道, lit. "way of the warrior") is a Japanese word literally meaning "the way of the warrior": 武 means «warrior, military, chivalry, arms (bu, ぶ)», 士 means «man or person, particularly one who is well-respected (shi, し)», 道 means «road, path, way (do, どう)».[13] In Japanese, the samurai are generally called Bushi (武士). It means «warrior or samurai (bushi, ぶし)».[14]

Historical development

Early history to 16th century

Many early literary works of Japan talk of warriors, but the term bushidō does not appear in text until the Edo period.[15] The code which would become Bushido was conceptualized during the late-Kamakura period (1185–1333) in Japan.[16] Since the days of the Kamakura shogunate, the “way of the warrior” has been an integral part of Japanese culture.[17][4]

During the Genna era (1615–1624) of the Edo period and later, the concept of "the way of the gentleman" (Shidō) was newly established by the philosopher and strategist Yamaga Sokō (1622–1685) and others who tried to explain this value in the morality of the Confucian Cheng–Zhu school. For the first time, Confucian ethics (such as Honor and Humanity", "filial piety") became the norm required by samurai.[18]

The first mention of this word is made in the Koyo Gunkan, written around 1616, but the appearance of bushido is linked to that of feudal Japan and the first shogun at the time of Minamoto no Yoritomo in the 12th century. However, the own moral dimension bushido gradually appears in the warrior culture and landmark in stories and military treaties only from the 14th and 15th century.[19] We thus note a permanence of the modern representation of its antiquity in Japanese culture and its diffusion.

Thus, at the time of the Genpei War, it was called “Way of the Bow and the Horse” (弓馬の道, kyūba no michi)[20] because of the major importance of this style of combat for the warriors of the time, and because it was considered a traditional method, that of the oldest samurai heroes, such as Prince Shōtoku, Minamoto no Yorimitsu and Minamoto no Yoshiie (Hachimantarō). According to Louis Frédéric, the kyūba no michi appeared around the 10th century as a set of rules and unwritten customs that samurai were expected to comply.[21]

Towards the 10th and 11th centuries we began to use expressions such as the way of the man-at-arms (Tsuwamon no michi), the way of the bow and arrows (Kyûsen / kyûya no Michi), the way of the bow and the horse (Kyûba no Michi). These expressions refer to practices which are the ancestors of the way of the warrior (bushidô) but they did not then imply any relation whatsoever to a morality. These were only practices focused on training for real combat and which therefore had to do with the samurai ways of life in the broad sense.[20]

The world of warriors which developed […] in the medieval period (12th – 16th century) was […] placed under the domination of the Buddhist religion […]. Buddhism makes the prohibition of killing living beings one of its main principles. […] Faced with death, some samurai thought they had inherited bad karma […] others knew they were doing evil. The Buddhist notion of impermanence (Mujo) tended to express a certain meaning to the fragility of existence, […]. Beliefs in the pure land of Buddha Amida […] allowed some warriors to hope for an Amidist paradise […]. Zen Buddhism with its doctrine of the oneness between life and death was also appreciated by many samurai […]. The world of medieval warriors remained a universe still largely dominated by the supernatural, and the belief in particular, in the tormented souls of warriors fallen in combat (who) returned almost obsessively in the dreams of the living. This idea also ensured the success of the Noh theater.[22]

The different editions of the Heike Monogatari shed light on the notion of the way:

in the Kakuichi version it is noted (regarding the declaration of the vassals of the Taira when they abandon the ancient capital of Fukuhara) 'according to the custom (narai) of who on horseback uses the air and arrows duplicity and the worst shame 'instead of' as is the custom of those who follow the Way of bow and arrows, betraying one's lord can only bring shame one's life during '[… ] 'custom' (naraï) is clearly mentioned here but there is no longer any question of 'way'. Even in the Engyô version, the Way of the Bow and the Arrows refers directly to the warriors and their way of life but the word 'way' (Michi), here, has no moral connotation.[23]

This is perfectly clear in the anecdote of the abandonment of prisoner Michitsune by his brother Michikiyo who declares "whoever was caught alive deserves only death". Angry Mitchitsune retorts "that a warrior is caught alive, isn't that a habit?". Habit or custom "narai" indicates a frequent situation without moral connotation even if it can be subject to discussion.[23]

The first proper Japanese central government was established around 700 CE. Japan was ruled by the Emperor (Tennō) with bureaucratic support of the aristocracy. They gradually lost control of their armed servants: the samurai. The samurai is similar to “the old English cniht (knecht, knight), guards or attendants,”.[24] By the mid-12th century the samurai class seized control. The samurai (bushi) ruled Japan with the shogun (将軍) as the overlord until the mid 19th century. The shogun was originally the Emperor’s military deputy.

Compiled over the course of three centuries, beginning in the 1180s, the Heike Monogatari depicts an idealized story of the Genpei War with a struggle between two powerful samurai clans, the Minamoto and the Taira at the end of the 12th century. Clearly depicted throughout the epic is the ideal of the cultivated warrior.[25] During the early modern era, these ideals were vigorously pursued in the upper echelons of warrior society and recommended as the proper form of the Japanese man of arms. The influence of Shinto, Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism in the Bushido's early development instilled among those who live by the code a religious respect for it. Yamaga-Soko, the Japanese philosopher given credit for establishing Bushido, said that "the first and surest means to enter into communion with the Divine is by sincerity."[1]

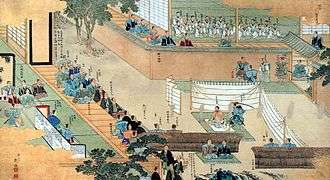

During the Muromachi period (1336–1573) the way of the warrior began to refine by inserting in their daily activities, alongside martial training, Zen meditation, painting, ikebana, the tea ceremony, poetry and literature.[4]

Carl Steenstrup noted that 13th- and 14th-century writings (gunki monogatari) "portrayed the bushi in their natural element, war, eulogizing such virtues as reckless bravery, fierce family pride, and selfless, at times senseless devotion of master and man".

The sayings of Sengoku-period retainers and warlords such as Katō Kiyomasa and Nabeshima Naoshige were generally recorded or passed down to posterity around the turn of the 16th century when Japan had entered a period of relative peace. In a handbook addressed to "all samurai, regardless of rank", Katō states:

- "If a man does not investigate into the matter of bushidō daily, it will be difficult for him to die a brave and manly death. Thus, it is essential to engrave this business of the warrior into one's mind well."

Katō was a ferocious warrior who banned even recitation of poetry, stating:

- "One should put forth great effort in matters of learning. One should read books concerning military matters, and direct his attention exclusively to the virtues of loyalty and filial piety....Having been born into the house of a warrior, one's intentions should be to grasp the long and the short swords and to die."[26]

Nabeshima Naoshige says similarly, that it is shameful for any man to die without having risked his life in battle, regardless of rank, and that "bushidō is in being crazy to die. Fifty or more could not kill one such a man". However, Naoshige also suggests that "everyone should personally know exertion as it is known in the lower classes".[26]

In Koyo Gunkan (1616), Bushido is a survival technique for individual fighters, and it aims to make the development of the self and the clan troupe advantageous by raising the samurai name. He also affirms that he seeks a lord who praises himself for wandering, as reflected in Tōdō Takatora (1556–1630)'s deceased memoir that "“A samurai cannot be called a samurai until he has changed his lords seven times.” Also, as symbolized by Asakura Norikage (1477–1555), "The warrior may be called a beast or a dog; the main thing is winning." as symbolized by Asakura Norikage, it is essential to win the battle even with the slander of cowardice. The feature is that it also contains the cold-hearted philosophy. These are mainly related to the way of life as a samurai, and they are the teachings of each family, and they are also equivalent to the treatment of vassals.

While the Kōyō Gunkan marks the first recorded reference to Bushido by name, it is not considered the most formidable historical document characterizing this code of conduct. As Bushido is a code of behavior, there is no single set of principles regarded as ‘true’ or ‘false’, but rather varying perceptions widely regarded as formidable throughout different centuries. Emphasized by Thomas Cleary, “Confucianism, Buddhism, and Shinto were each represented by a variety of schools, and elements of all three were commonly combined in Japanese culture and customs. Asthe embodiment of Samurai culture, Bushido is correspondingly diverse, drawing selectively on elements of all these traditions to articulate the ethos and discipline of the warrior.[27]

By the mid-16th century, several of Japan’s most powerful warlords began to vie for supremacy over territories amidst the Kyoto government’s waning power. With Kyoto’s capture by the warlord Oda Nobunaga in 1573, the Muromachi period concluded.[28]

Despite the war-torn culmination of this era and the birth of the Edo period, Samurai codes of conduct continued to extend beyond the realms of warfare. Forms of Bushido-related Zen Buddhism and Confucianism also emerged during this period.[29] A Samurai adhering to Bushido-like codes was expected to live a just and ethical social life; honoring the practices of the gentry in the absence of military campaigns.[29]

17th to 19th centuries

Japan enjoyed two and a half centuries of relative peace during the Edo period (1600 to the mid-19th century). The Tokugawa shogunate (1603–1867) codified aspects of the Samurai warrior values and formalized them into parts of the Japanese feudal law.[5] In addition to the "house codes" issued in the context of the fiefdoms (han) and texts that described the right behavior of a warrior (such as the Hagakure), the first Buke shohatto (Laws for the Military Houses, 武家諸法度) was issued by the government in 1615, which prescribed to the lords of the fiefdoms (daimyo) and the samurai warrior aristocracy responsibilities and activities, the rules of conduct, simple and decent clothing, the correct supply in case of official visits, etc.[4] The edicts were reissued in 1629, and in 1635, by the third shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu. The new edicts made clear the shogunate's authority and its desire to assert control.[30]

During this period, the samurai class played a central role in the policing and administration of the country. The bushidō literature of this time contains much thought relevant to a warrior class seeking more general application of martial principles and experience in peacetime, as well as reflection on the land's long history of war. The literature of this time includes:

- Budo Shōshinshu (武道初心集) by Taira Shigesuke, Daidōji Yūzan (1639–1730)

- Hagakure as related by Yamamoto Tsunetomo to Tsuramoto Tashiro.

- Bugei Juhappan (武芸十八般)

- A Book of Five Rings by Miyamoto Musashi

The Hagakure contains many sayings attributed to Sengoku-period retainer Nabeshima Naoshige (1537–1619) regarding bushidō related philosophy early in the 18th century by Yamamoto Tsunetomo (1659–1719), a former retainer to Naoshige's grandson, Nabeshima Mitsushige. The Hagakure was compiled in the early 18th century, but was kept as a kind of "secret teaching" of the Nabeshima clan until the end of the Tokugawa bakufu (1867).[31] His saying, "I have found the way of the warrior is death", was a summation of the focus on honour and reputation over all else that bushidō codified.[32]

Tokugawa-era rōnin, scholar and strategist Yamaga Sokō (1622–1685) wrote extensively on matters relating to bushidō, bukyō (a "warrior's creed"), and a more general shidō, a "way of gentlemen" intended for application to all stations of society. Sokō attempts to codify a kind of "universal bushidō" with a special emphasis on "pure" Confucian values, (rejecting the mystical influences of Tao and Buddhism in Neo-Confucian orthodoxy), while at the same time calling for recognition of the singular and divine nature of Japan and Japanese culture. These radical concepts—including ultimate devotion to the Emperor, regardless of rank or clan—put him at odds with the reigning shogunate. He was exiled to the Akō domain, (the future setting of the 47 Rōnin incident), and his works were not widely read until the rise of nationalism in the early 20th century.

The aging Yamamoto Tsunetomo's interpretation of bushidō is perhaps more illustrative of the philosophy refined by his unique station and experience, at once dutiful and defiant, ultimately incompatible with the laws of an emerging civil society. Of the 47 rōnin—to this day, generally regarded as exemplars of bushidō—Tsunetomo felt they were remiss in hatching such a wily, delayed plot for revenge, and had been over-concerned with the success of their undertaking. Instead, Tsunetomo felt true samurai should act without hesitation to fulfill their duties, without regard for success or failure.

This romantic sentiment is of course expressed by warriors throughout history, though it may run counter to the art of war itself. This ambivalence is found in the heart of bushidō, and perhaps all such "warrior codes". Some combination of traditional bushidō's organic contradictions and more "universal" or "progressive" formulations (like those of Yamaga Sokō) would inform Japan's disastrous military ambitions in the 20th century.

19th to 21st centuries

Recent scholarship in both Japan and abroad has focused on differences between the samurai caste and the bushidō theories that developed in modern Japan. Bushidō or the samurai ethos changed considerably over time. Bushidō in the prewar period was often emperor-centered and placed much greater value on the virtues of loyalty and self-sacrifice than did many Tokugawa-era interpretations.[33]

Meiji Bushido

Prominent scholars consider the type of bushido that was prevalent since the Meiji period (1868–1912) as “Meiji bushidō” (明治武士道). Such as University of Tokyo professor of ethics Kanno Kakumyō (菅野覚明) wrote a book that supports it: Bushidō no gyakushū (武士道の逆襲), 2004. Meiji Bushido simplified the primary attributes that it ignored the actual samurai (bushi).[34] The samurai originally fought for personal matters, honor of their family and clan. When Japan was unified the samurai's raison 'd'etre changed from personal to public as bureaucrats with administrative functions. When the samurai class abolished itself, their public function became national to form a modern nation-state. With the disappearance of the separate social classes, some values were transferred to the whole population, such as the feeling of loyalty, which was addressed to the emperor.[4] The author Yukio Mishima (1925–1970) asserted that “invasionism or militarism had nothing to do with bushidō from the outset.” According to Mishima a man of bushidō is someone who has a firm sense of self-respect, takes responsibility for his action, and sacrifices himself to embody that responsibility.

Bushidō was used as a propaganda tool by the government and military, who doctored it to suit their needs.[35] The original Imperial Rescript to Soldiers and Sailors of 1882 has the word hōkoku (報国) which means that you are indebted to your nation due to your birth in it and therefore you must return the debt through your exertion (physical or mental effort). This idea did not exist in earlier Bushido. Scholars of Japanese history agree that the bushidō that spread throughout modern Japan was not simply a continuation of earlier traditions.

"If, during the Middle Ages, letters became the cultural preserve of the aristocrats of the Imperial Court, in the Edo period, they were that of Confucian scholars. If letters are the sign of the teaching of Confucianism, it is that is to say of Chinese culture, the profession of arms embodies truly Japanese values. (...) The Opium War (1839–1842) was a trauma for Japan" since it ended with the invasion of China by the British. Along with the sense of urgency, one of the consequences created by the crisis has been the rise of nationalism, voices are raised in favor of the need to re-value the profession of arms. "The revival of bushidô was thus linked to nationalism. (...) The term becomes very frequent and with a positive connotation by the thinkers of the xenophobic movement of the years 1853–1867 favorable to the imperial restoration and takes a nationalist coloring absent at the end of the Middle Ages ". It disappeared again during the Meiji summer until it reappeared from the 1880s to symbolically express the loss of traditional values during the rapid introduction of Western civilization from 1868 and the feeling of urgency, again, to defend the magnificent Japanese tradition.[36] "Confucianism and Buddhism are embedded, then, in the traditional values to be defended against the West while in the Edo period bushido as a Japanese tradition was rather used as an alternative to Confucianism."[37]

The victory of Japan over China in 1895 "changes the paradigm, it is no longer the urgency but the pride of the tradition of bushido which is at the origin of military success[38] (...) abnegation and surpassing oneself" are put forward by forgetting "the moral hesitations of the warrior on the means of victory"[39]

Nitobe Inazo (1862–1933) published Bushido: The Soul of Japan[40][41] in the United States in 1900 as a result of encountering a lack of religious education in Japan in a conversation with local educators. In addition to politicians such as Theodore Roosevelt and President John F. Kennedy, the book also found many overseas readers such as Boy Scout founder Robert Baden-Powell, and in 1908, "Bushido"[42] as Sakurai Oson ([:ja:櫻井鴎村]) published a Japanese translation. Additionally, in 1938 (Showa 13) Nitobe's pupil Tadao Yanaihara published a translated paperback edition.[43] In Nitobe's Soul of Japan, "this was a discourse although different from that which the nationalists held on Bushido but of in a way, he joined them because he helped to increase their prestige and participated in the ambient mode of revival of the Way of the Warrior. Subsequently, after the defeat (...) nationalist theories on bushido were denounced but not the work of Nitobe Inazaö which escaped disavowal to the point that it even became the best representative of bushido trials in Japan."[44]

The entrepreneur Fukuzawa Yukichi appreciated Bushido and emphasized that maintaining the morale of scholars is the essence of the eternal life.[45][46] Nitoto Inazuke's submitted his book "Bushido" to Emperor Meiji and stated that "Bushido is prosperous here, assists Komo, and promotes the national style, so that the public will return to the patriotic virtues of loyal ministers." Bushido has slightly different requirements for men and women. For women, Bushido means guarding their chastity (when as the daughter of a samurai), educating their children, supporting their husbands, and maintaining their families.[47]

The researcher Oleg Benesch argued that the modern concept of bushidō changed throughout the modern era as a response to foreign stimuli in the 1880s. Such as the English concept of "gentlemanship", by Japanese with considerable exposure to Western culture. Nitobe Inazo's bushidō interpretations followed a similar trajectory, although he was following earlier trends. This relatively pacifistic bushidō was then hijacked and adapted by militarists and the government from the early 1900s onward as nationalism increased around the time of the Russo-Japanese War.[48]

After the Meiji Restoration, the martial arts etiquette represented by Ogasawara-ryū (小笠原流) popularized practice education for the people in 1938 (Showa 13).[49] The junshi suicide of General Nogi Maresuke and his wife on the death of Emperor Meiji occasioned both praise, as an example to the decaying morals of Japan, and criticism, explicitly declaring that the spirit of bushidō thus exemplified should not be revived.[50]

.jpg)

The industrialist Eiichi Shibusawa preached Bushido as necessary for future times, and the spirit of Japanese business from the Meiji era to the Taisho democracy was advocated, which became the backbone necessary for Japanese management.[51]

The Hoshina Memorandum provides evidence that Bushido principles affected Japanese society and culture across social strata during the World War II era, yet the warrior code was intimately involved in the buildup of these values prior to the breakout of the war. William R. Patterson suggests that Bushido influenced martial arts and education corresponded with nationalistic ideals which were prevalent prior to 1941.[52]

In Bushido's Role In the Growth of Pre-World War II Japanese Nationalism, Patterson describes how competency of tradition through Bushido-inspired martial skills enabled society to remain interconnected; harnessing society’s reverence of ancestral practices for national strength.[53]

"The martial arts were seen as a way not to maintain ancient martial techniques but instead to preserve a traditional value system, Bushido, that could be used to nurture national spirit. In the midst of modernization, the Japanese were struggling to hold onto some traditions that were uniquely Japanese and that could unify them as countrymen. Jigoro Kano, for example, argued that "because judo developed based on the martial arts of the past, if the martial arts practitioners of the past had things that are of value, those who practice judo should pass all those things on. Among these, the samurai spirit should be celebrated even in today's society" (Kano, 2005: 126)"[53]

During pre-World War II and World War II Shōwa Japan, bushido was pressed into use for militarism,[54] to present war as purifying, and death a duty.[55] This was presented as revitalizing traditional values and "transcending the modern".[56] Bushidō would provide a spiritual shield to let soldiers fight to the end.[57] When giving orders general Hideki Tojo routinely slapped the faces of the men under his command, saying that face-slapping was a "means of training" men who came from families that were not part of the samurai caste, and for whom bushido was not second nature.[58] Tojo wrote a chapter in the book Hijōji kokumin zenshū (Essays in time of national emergency) which was published in March 1934 by the Army Ministry. It called for Japan to become a totalitarian "national defense state".[59] This book included 15 essays by senior generals and argued that Japan defeated Russia in the Russo-Japanese war (1904–05) because bushidō gave the Japanese superior willpower as the Japanese did not fear death unlike the Russians who wanted to live, and the requirement to win the inevitable next war was to repeat the example of the Russian-Japanese war on a much greater scale by creating the "national defense state" and mobilize the entire nation for war.[60]

As the war turned, the spirit of bushidō was invoked to urge that all depended on the firm and united soul of the nation.[61] When the Battle of Attu was lost, attempts were made to make the more than two thousand Japanese deaths an inspirational epic for the fighting spirit of the nation.[62] Arguments that the plans for the Battle of Leyte Gulf, involving all Japanese ships, would expose Japan to serious danger if they failed, were countered with the plea that the Navy be permitted to "bloom as flowers of death".[63] The Japanese believed that indoctrination in bushido would give them the edge as the Japanese longed to die for the Emperor, while the Americans were afraid to die. However, superior American pilot training and airplanes meant the Japanese were outclassed by the Americans.[64] The first proposals of organized Kamikaze suicide attacks met resistance because although bushidō called for a warrior to be always aware of death, they were not to view it as the sole end. Nonetheless, the desperate straits brought about acceptance[65] and such attacks were acclaimed as the true spirit of bushidō.[66]

As Japan continued its modernization in the early 20th century, her armed forces became convinced that success in battle would be assured if Japanese soldiers, sailors, and airmen had the “spirit” of Bushido. ... The result was that the Bushido code of behavior “was inculcated into the Japanese soldier as part of his basic training.” Each soldier was indoctrinated to accept that it was the greatest honor to die for the Emperor and it was cowardly to surrender to the enemy. ... Bushido therefore explains why the Japanese in the NEI so mistreated POWs in their custody. Those who had surrendered to the Japanese—regardless of how courageously or honorably they had fought—merited nothing but contempt; they had forfeited all honor and literally deserved nothing. Consequently, when the Japanese murdered POWs by shooting, beheading, and drowning, these acts were excused since they involved the killing of men who had forfeited all rights to be treated with dignity or respect. While civilian internees were certainly in a different category from POWs, it is reasonable to think that there was a “spill-over” effect from the tenets of Bushido.

Japanese propaganda during World War II claimed that prisoners of war denied being mistreated, and declared that they were being well-treated by virtue of bushidō generosity.[68] Broadcast interviews with prisoners were also described as being not propaganda but out of sympathy with the enemy, such sympathy as only bushidō could inspire.[69]

An example of Japanese soldiers who followed tenants of the Bushido code: during the Second World War, many Japanese infantry were trapped on the island of Guam, surrounded by the Allied forces and low on supplies.[70] Despite being outnumbered and in horrific conditions, many soldiers refused to surrender. As indicated by Dixon and colleagues, “They continued to honor the Bushido code, believing that “to rush into the thick of battle and to be slain in it, is easy enough... but, it is true courage to live when it is right to live, and to die only when it is right to die.[71]

After World War 2, the Bank of Japan changed the design of the banknotes in 1984, using Fukuzawa Yukichi for the 10,000 yen note, Nitobe Inazō for the 5,000 yen note, and Natsume Soseki for the 1,000 yen note. These three people all expressed their positive appreciation of Bushido. Although the views of the three people are similar and there are subtle differences, they also said that the Japanese in the Meiji period were quite influenced by Bushido.[46]

Contemporary Bushido

We can consider that today bushido is still present in the social and economic organization of Japan, because it is the mode of thought which historically structured the capitalist activity in the 20th century. Business relations, the close relationship between the individual and the group to which he or she belongs, the notions of trust, respect and harmony within the Japanese business world are directly based on bushido. This would therefore be at the origin of the ideology of industrial harmony (ja:労使協調) of modern Japan, which allowed the country to become, with the Japanese economic miracle of the post-war years of the 1950-1960s, the leader of the Asian economy.

Business

Bushido affects a myriad of aspects in Japanese society and culture. In addition to impacts on military performance, media, entertainment, martial arts, medicine and social work, the Bushido code has catalyzed corporate behavior. Shinya Fujimura examines Samurai ethics in the academic article The Samurai Ethics: A Paradigm for Corporate Behavior. Bushido principles indicate that rapid economic growth does not have to be a goal of modern existence.[72] Relatedly, economic contentment is attainable regardless of hegemonic gross-domestic product statistics.[73] In Fujimura’s words, “The tradition permeates the country's corporate culture and has informed many of its social developments.”[74] Fujimura states egalitarian principles practiced by the Samurai have permeated through modern business society and culture. Principles like Honorable Poverty, “Seihin,” encourage those with power and resources to share their wealth, directly influencing national success.[74] Bushido also provides enterprises with social meaning. Eloquently described by Fujimura, “The moral purpose that bushido articulates transcends booms and busts….it is often said that a Japanese company is like a family, with executives caring about employees and employees showing respect to executives. Bushido, then, is part of the basis for a sense of national identity and belonging—an ideal that says the Japanese are one people, in it together.[75]

Communication

In utilization of Bushido’s seven virtues, the Samurai code has been renewed to contribute towards development of communication skills between adult Japanese couples. Composed in 2012, the empirical document The Bushido Matrix for Couple Communication identifies a methodology which can be employed by counseling agents to guide adults in self-reflection and share emotions with their partner. This activity centers on the ‘Bushido Matrix Worksheet’ (BMW).[76] The authors accentuate, “practicing Bushido virtues can ultimately enhance intra- and interpersonal relationship, beginning with personal awareness and extending to couple awareness.[77] When utilizing the matrix, a couple is asked to identify one of the seven virtues and apply it to their past and current perceptions surrounding its prevalence in their lives.[77] If individuals identify their relationship to be absent that specific virtue, they may now ponder of its inclusion for their benevolence.[78]

Martial arts

Both bushido and other martial arts are different in the modern world. Modern Bushido focuses more on self-defense, fighting, sports, tournaments and just physical fitness training. While all of these things are important to the martial arts, a much more important thing is missing, which is personal development. Bushido’s art taught soldiers the important secrets of life, how to raise children, how to dress, how to treat family and other people, how to cultivate personality, things related to finances. All of these things are important to be a respected soldier. Although the modern Bushido is guided by eight virtues, that alone is not enough. Bushido not only taught him how to become a soldier, but all the sages of life. The warrior described by Bushido is not a profession but a way of life. It is not necessary to be in the army to be a soldier. The term “warrior” refers to a person who is fighting for something, not necessarily physically. Man is a true warrior because of what is in his heart, mind, and soul. Everything else is just tools in the creation to make it perfect. Bushido is a way of life that means living in every moment, honorably and honestly. All this is of great importance in the life of a soldier, both now and in the past.[79]

In the book Kata – The true essence of Budo martial arts? Simon Dodd and David Brown state that Bushido spiritualism lead the martial art ‘Bujutsu’ to evolve into modern ‘Budō’ (武道).[80] For their analysis, they review the Kamakura period to reiterate the influence Bushido held in martial arts evolution.[80] They distinctly state, “For clarity any reference to bushido is in relation to bujutsu within the Kamakura to pre‐Meiji restoration period (pre-1868), and any links to budo are referring to the modern form of the martial arts.”[80] To supplement this affirmation Dodd and Brown discuss the variance between the meaning behind Bujutsu and Budo. According to Todd and Brown Budo is a redevelopment of traditional Kamakura period martial arts principles; Budo defines the way of the warrior through roots in religious ethics and philosophy. The martial art form’s translation binds it to Confucian and Buddhist concepts of Bushido:[80]

Respected karate‐ka Kousaku Yokota explains how Bujutsu could be considered the “art of fighting or killing” and encompasses a ‘win at all costs’ mentality required for battlefield survival (Yokota, 2010, p. 185). Conversely, Budo could be considered the “artof living or life” and enables a practitioner to live “honestly and righteously or at least with principles”. Expanding on both these points, Deshimaru (1982, p. 11; p. 46) reports that the ideogram for bu means to “the cease the struggle” and that “in Budo the point is...to find peace and mastery of the self”[80]

The iaidō, in its transmission and its practice, is the martial art which takes up in its entirety Bushido by the etiquette, the code of honor, the dress, the carrying of the sword and the fight against oneself rather than against the opponent. Modern combat sports like kendo derive their philosophy from Bushido; Unlike other martial arts, prolonged contact or multiple hits tend to be disadvantaged in favor of simple, clean attacks on the body. Bushido has also inspired the code of honor for disciplines such as aikijutsu, aikido, aikibudo, judo, jujitsu, Kyudo, or the chanbara.

Tenets

Bushidō expanded and formalized the earlier code of the samurai, and stressed sincerity, frugality, loyalty, mastery of martial arts, and honour to the death. Under the bushidō ideal, if a samurai failed to uphold his honor he could only regain it by performing seppuku (ritual suicide).[81]

In an excerpt from his book Samurai: The World of the Warrior,[82] historian Stephen Turnbull describes the role of seppuku in feudal Japan:

In the world of the warrior, seppuku was a deed of bravery that was admirable in a samurai who knew he was defeated, disgraced, or mortally wounded. It meant that he could end his days with his transgressions wiped away and with his reputation not merely intact but actually enhanced. The cutting of the abdomen released the samurai’s spirit in the most dramatic fashion, but it was an extremely painful and unpleasant way to die, and sometimes the samurai who was performing the act asked a loyal comrade to cut off his head at the moment of agony.

Bushidō varied dramatically over time, and across the geographic and socio-economic backgrounds of the samurai, who represented somewhere between 5% and 10% of the Japanese population.[83] The first Meiji-era census at the end of the 19th century counted 1,282,000 members of the "high samurai", allowed to ride a horse, and 492,000 members of the "low samurai", allowed to wear two swords but not to ride a horse, in a country of about 25 million.[84]

Some versions of bushidō include compassion for those of lower station, and for the preservation of one's name.[26] Early bushidō literature further enforces the requirement to conduct oneself with calmness, fairness, justice, and propriety.[26] The relationship between learning and the way of the warrior is clearly articulated, one being a natural partner to the other.[26]

Other pundits pontificating on the warrior philosophy covered methods of raising children, appearance, and grooming, but all of this may be seen as part of one's constant preparation for death—to die a good death with one's honor intact, the ultimate aim in a life lived according to bushidō. Indeed, a "good death" is its own reward, and by no means assurance of "future rewards" in the afterlife. Some samurai, though certainly not all (e.g., Amakusa Shirō), have throughout history held such aims or beliefs in disdain, or expressed the awareness that their station—as it involves killing—precludes such reward, especially in Buddhism. Japanese beliefs surrounding the samurai and the afterlife are complex and often contradictory, while the soul of a noble warrior suffering in hell or as a lingering spirit occasionally appears in Japanese art and literature, so does the idea of a warrior being reborn upon a lotus throne in paradise[85]

Eight virtues of Bushidō (as envisioned by Nitobe Inazō)

The bushidō code is typified by eight virtues:[86]

- Righteousness (義, gi)

Be acutely honest throughout your dealings with all people. Believe in justice, not from other people, but from yourself. To the true warrior, all points of view are deeply considered regarding honesty, justice and integrity. Warriors make a full commitment to their decisions.

Hiding like a turtle in a shell is not living at all. A true warrior must have heroic courage. It is absolutely risky. It is living life completely, fully and wonderfully. Heroic courage is not blind. It is intelligent and strong.

- Benevolence, Compassion (仁, jin)

Through intense training and hard work the true warrior becomes quick and strong. They are not as most people. They develop a power that must be used for good. They have compassion. They help their fellow men at every opportunity. If an opportunity does not arise, they go out of their way to find one.

True warriors have no reason to be cruel. They do not need to prove their strength. Warriors are not only respected for their strength in battle, but also by their dealings with others. The true strength of a warrior becomes apparent during difficult times.

When warriors say that they will perform an action, it is as good as done. Nothing will stop them from completing what they say they will do. They do not have to 'give their word'. They do not have to 'promise'. Speaking and doing are the same action.

Warriors have only one judge of honor and character, and this is themselves. Decisions they make and how these decisions are carried out are a reflection of who they truly are. You cannot hide from yourself.

Warriors are responsible for everything that they have done and everything that they have said and all of the consequences that follow. They are immensely loyal to all of those in their care. To everyone that they are responsible for, they remain fiercely true.

- Self-Control (自制, jisei)

Associated virtues

- Filial piety (孝, kō)

- Wisdom (智, chi)

- Fraternity (悌, tei)

Modern translations

Modern Western translation of documents related to bushidō began in the 1970s with Carl Steenstrup, who performed research into the ethical codes of famous samurai including Hōjō Sōun and Imagawa Sadayo.[87]

Primary research into bushidō was later conducted by William Scott Wilson in his 1982 text Ideals of the Samurai: Writings of Japanese Warriors. The writings span hundreds of years, family lineage, geography, social class and writing style—yet share a common set of values. Wilson's work also examined older Japanese writings unrelated to the warrior class: the Kojiki, Shoku Nihongi, the Kokin Wakashū and the Konjaku Monogatari, as well as the Chinese Classics (the Analects, the Great Learning, the Doctrine of the Mean, and the Mencius).

In May 2008, Thomas Cleary translated a collection of 22 writings on bushidō by warriors, scholars, political advisers, and educators, spanning 500 years from the 14th to the 19th centuries. Titled Training the Samurai Mind: A Bushido Sourcebook, it gave an insider's view of the samurai world: "the moral and psychological development of the warrior, the ethical standards they were meant to uphold, their training in both martial arts and strategy, and the enormous role that the traditions of Shintoism, Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism had in influencing samurai ideals".

Literature

Examples of Japanese literature related to Bushido from the 13th to the 20th century:

- Hojo Shigetoki – The Message of Master Gokurakuji (1198–1261)

- Shiba Yoshimasa – The Chikubashō (1350–1410)

- Imagawa Sadayo – The Regulations of Imagawa Ryoshun (1325–1420)

- Asakura Toshikage – The Seventeen-Article Injunction of Asakura Toshikage (1428–1481)

- Hōjō Sōun – The Twenty-One Precepts Of Hōjō Sōun (1432–1519)

- Asakura Norikage – The Recorded Words Of Asakura Soteki (1474–1555)

- Takeda Shingen – The Iwamizudera Monogatari (1521–1573)

- Takeda Nobushige – Opinions In Ninety-Nine Articles (1525–1561)

- Nabeshima Naoshige – Lord Nabeshima's Wall Inscriptions (1538–1618)

- Torii Mototada – The Last Statement of Torii Mototada (1539–1600)

- Katō Kiyomasa – The Precepts of Kato Kiyomasa (1562–1611)

- Kuroda Nagamasa – Notes On Regulations (1568–1623)

- Taira Shigesuke, Daidōji Yūzan – Bushido Shoshinshu

- Yamamoto Tsunetomo and Tsuramoto Tashiro – Hagakure (1716)

- Miyamoto Musashi – The Book of Five Rings (1645)

- Hideki Tojo & senior generals – Hijōji Kokumin Zenshū (Essays in Time of National Emergency) (1934)

Major figures associated with Bushidō

- Asano Naganori

- Imagawa Ryōshun

- Katō Kiyomasa

- Sakanoue no Tamuramaro

- Honda Tadakatsu

- Tokugawa Ieyasu

- Torii Mototada

- Sasaki Kojirō

- Saigō Takamori

- Yamaga Sokō

- Yamamoto Tsunetomo

- Yamaoka Tesshū

- Yukio Mishima

- Hijikata Toshizō

- Miyamoto Musashi

- Kusunoki Masashige

- Gichin Funakoshi

- Kanō Jigorō

- Dom Justo Takayama

- Morihei Ueshiba

- Takeda Sōkaku

- Hideki Tojo

See also

References

- Matthews, Warren (2010). World Religions. Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning. p. 199. ISBN 9780495603856.

- Nitobe, Inazo (2010). Bushido, The Soul of Japan. Kodansha International. p. 81. ISBN 9784770050113.

- "The Zen of Japanese Nationalism", by Robert H. Sharf, in Curators of the Buddha, edited by Donald Lopez, p. 111

- Bushido entry (in Italian) in the Enciclopedia italiana

- ""Tokugawa shogunate"". Archived from the original on 2018-06-12. Retrieved 2017-06-06.

- Japanese Wikipedia page about Bushido

- Willcock, Hiroko (2008). The Japanese Political Thought of Uchimura Kanzō (1861–1930): Synthesizing Bushidō, Christianity, Nationalism, and Liberalism. Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 978-0773451513.

Koyo gunkan is the earliest comprehensive extant work that provides a notion of Bushido as a samurai ethos and the value system of the samurai tradition.

- Ikegami, Eiko, The Taming of the Samurai, Harvard University Press, 1995. p. 278

- Kasaya, Kazuhiko (2014). 武士道 第一章 武士道という語の登場 [Bushido Chapter I Appearance of the word Bushido] (in Japanese). NTT publishing. p. 7. ISBN 978-4757143227.

- Friday, Karl F. "Bushidō or Bull? A Medieval Historian's Perspective on the Imperial Army and the Japanese Warrior Tradition". The History Teacher, Vol. 27, No. 3 (May 1994), pp. 340.

- Nitobe, Inazō (1899). Bushidō: The soul of Japan.

- Arthur May Knapp (1896). "Feudal and Modern Japan". Archived from the original on 2012-11-04. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- "Jisho.org". Retrieved 2020-08-01.

- "Jisho.org". Retrieved 2020-08-01.

- "The Zen of Japanese Nationalism," by Robert H. Sharf, in Curators of the Buddha, edited by Donald Lopez, p. 111

- Tasuke Kawakami, "Bushidō In Its Formative Period." The Annals Of The Hitotsubashi Academy no. 1: 65. 1952. JSTOR Journals, EBSCOhost (accessed August 31, 2018). 67.

- Department of Asian Art. “Kamakura and Nanbokucho Periods (1185–1392).” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–.

- 多田顕『武士道の倫理 山鹿素行の場合』永安幸正編集・解説 麗澤大学出版会 2006

- Shin'ichi, Saeki (2008). "Figures du samouraï dans l'histoire japonaise: Depuis Le Dit des Heiké jusqu'au Bushidô". Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales. 4: 877–894.

- Samouraïs 2017, pp. 63–64

- Encyclopaedia of Asian civilizations

- Samouraïs 2017, p. 20-21

- Samouraïs 2017, p. 64-66.

- Inazo Nitobe, Bushido: The Warrior’s Code (Ohara Publications, 1979), p. 14. Bushido is available on the Internet as a Google book and as part of Project Gutenberg http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/12096

- Shimabukuro, Masayuki; Pellman, Leonard (2007). Flashing Steel: Mastering Eishin-Ryu Swordsmanship, 2nd edition. Berkeley, CA: Blue Snake Books. p. 2. ISBN 9781583941973.

- William Scott Wilson, Ideals of the Samurai: Writings of Japanese Warriors (Kodansha, 1982) ISBN 0-89750-081-4

- Thomas Cleary, Samurai Wisdom: Lessons from Japan’s Warrior Culture; Five Classic Texts on Bushido. Vermont: Tuttle Publishing, 2009. 28

- Kawakami, Tasuke. "Bushidō In Its Formative Period." The Annals Of The Hitotsubashi Academy no. 1: 65. 1952. JSTOR Journals. EBSCOhost. Page: 82-83

- Tasuke, p. 78

- Hall (Editor), John Whitney (1988). The Cambridge history of Japan Vol. 4: Early Modern Japan. James L. McClain. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22352-0. OCLC 17483588.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "The Samurai Series: The Book of Five Rings, Hagakure -The Way of the Samurai & Bushido – The Soul of Japan" ELPN Press (November, 2006) ISBN 1-934255-01-7

- Meirion and Susie Harries, Soldiers of the Sun: The Rise and Fall of the Imperial Japanese Army p 7 ISBN 0-394-56935-0

- Eiko Ikegami. The Taming of the Samurai: Honorific Individualism and the Making of Modern Japan. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995.

- Kanno Kakumyō, Bushidō no gyakushū (Kōdansha, 2004), p. 11.

- Karl Friday. Bushidō or Bull? A Medieval Historian's Perspective on the Imperial Army and the Japanese Warrior Tradition. The History Teacher, Volume 27, Number 3, May 1994, pages 339–349. Archived 2010-12-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Bushido et les conférences de Yamaoka Tesshu. Tokyo: Tokyo Koyûkan. 1902.

- Samouraïs 2017, pp. 81–83

- Bushido shi jûkô. Tokyo: Tokyo Meguro Shoten. 1927.

- Samouraïs 2017, p. 83

- Nitobe, Inazo (1900). Bushido: The Soul of Japan. -(Project Gutenberg)の電子テキスト全文

- グーテンベルク・プロジェクトの新渡戸稲造 『武士道』(英文)

- 「武士道 / 新渡戸稲造著,桜井彦一郎訳」(近代デジタルライブラリー)

- 新渡戸稲造 (1938). 武士道. 岩波文庫. 矢内原忠雄訳. 岩波書店. ISBN 4-00-331181-7.

- Samouraïs 2017, pp. 85–86

- 瘠我慢の説 Archived 2014-01-16 at the Wayback Machine

- 许介鳞:日本「武士道」揭谜 (Japanese "Bushido" the mysteries exposed) Archived 2014-01-12 at the Wayback Machine

- 许介鳞:日本「武士道」揭谜 Archived 2014-01-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Oleg Benesch. Inventing the Way of the Samurai: Nationalism, Internationalism, and Bushido in Modern Japan. Archived 2016-10-18 at the Wayback Machine Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014. ISBN 0198706626, ISBN 9780198706625

- Ogasawara Ritual Law

- Herbert P. Bix, Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan p 42-3 ISBN 0-06-019314-X

- Bushido according to Shibusawa Eiichi: The Analects and Business and Samurais in the World. Amazon.com. 2017.

- William R. Patterson, "Bushido's Role in the Growth of Pre-World War II Japanese Nationalism." Journal Of Asian Martial Arts 17, no. 3: 8. 2008. Supplemental Index, EBSCOhost (accessed September 8, 2018). 9.

- Patterson 2008, p. 14

- "No Surrender: Background History Archived 2011-07-18 at the Wayback Machine"

- David Powers, "Japan: No Surrender in World War Two Archived 2019-09-29 at the Wayback Machine"

- John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p1 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

- Richard Overy, Why the Allies Won p 6 ISBN 0-393-03925-0

- Browne, Courtney (1998). Tojo The Last Banzai. Boston: Da Capo Press. p. 40. ISBN 0306808447.

- Bix, p. 277.

- Bix, Herbert P. (September 4, 2001). Hirohito and the making of modern Japan. HarperCollins. p. 277. ISBN 978-0-06-093130-8. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 334 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 444 Random House New York 1970

- John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936–1945 p 539 Random House New York 1970

- Willmott, H.P. (1984). June 1944. Poole, United Kingdom: Blandford Press. p. 213. ISBN 0-7137-1446-8.

- Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 356 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 360 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- Borch, Fred (2017). Military Trials of War Criminals in the Netherlands East Indies 1946–1949. Oxford University Press. pp. 31–32. ISBN 0191082953. Archived from the original on 2020-01-28. Retrieved 2019-01-22.

- Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 256 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 257 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- Boyd Dixon, Laura Gilda, and Lon Bulgrin. "The Archaeology of World War II Japanese Stragglers on the Island of Guam and the Bushido Code." Asian Perspectives no. 1: 110. 2012. JSTOR Journals, EBSCOhost (accessed August 30, 2018). 110

- Dixon, Gilda & Bulgrin 2012, p. 113

- Shinya Fujimura, "The Samurai Ethics: A Paradigm for Corporate Behavior." Harvard Kennedy School Review 11, 212–215. 2011. Academic Search Ultimate, EBSCOhost (accessed August 30, 2018). 212.

- Fujimura 2011, p. 213

- Fujimura 2011, p. 214

- Fujimura 2011, p. 215

- Li, Chi-Sing, Yu-Fen Lin, Phil Ginsburg, and Daniel Eckstein, "The Bushido Matrix for Couple Communication." Family Journal 20, no. 3: 299–305. 2012. Criminal Justice Abstracts, EBSCOhost (accessed August 30, 2018). 299.

- Li et al. 2012, p. 301

- Li et al. 2012, p. 302

- Sanders, B., 2012. Modern Bushido: Living a Life of Excellence.

- Dodd, Simon, and David Brown. "Kata – The true essence of Budo martial arts? / Kata – ¿ La verdadera esencia de las artes marciales Budo?" Revista De Artes Marciales Asiaticas 11, no. 1: 32–47. 2016. SPORTDiscus with Full Text, EBSCOhost (accessed August 30, 2018). Page 33-34

- "Bushido | Japanese history". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2017-08-01. Retrieved 2017-08-21.

- "ospreysamurai.com". www.ospreysamurai.com. Archived from the original on 2006-03-15. Retrieved 2006-03-05.

- Cleary, Thomas Training the Samurai Mind: A Bushido Sourcebook Shambhala (May 2008) ISBN 1-59030-572-8

- Mikiso Hane Modern Japan: A Historical Survey, Third Edition Westview Press (January 2001) ISBN 0-8133-3756-9

- Zeami Motokiyo "Atsumori"

- Bushido: The Soul of Japan

- "Monumenta Nipponica". Archived from the original on 2008-02-15.

External links and further reading

- Oleg Benesch. Inventing the Way of the Samurai: Nationalism, Internationalism, and Bushido in Modern Japan. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014. ISBN 0198706626, ISBN 9780198706625

- 易經道 Yijing Dao, 鳴鶴在陰 Calling crane in the shade, Biroco – The Art of Doing Nothing, 2002–2012, 馬夏 Ma, Xia, et. al.,

- "Bushido Arcade" a Contemporary translation of the Bushido

- William Scott Wilson, Ideals of the Samurai: Writings of Japanese Warriors (Kodansha, 1982) ISBN 0-89750-081-4

- Training the Samurai Mind: A Bushido Sourcebook by Thomas Cleary 288 pages Shambhala (May 13, 2008) ISBN 1-59030-572-8 ISBN 978-1590305720

- Katsumata Shizuo with Martin Collcutt, "The Development of Sengoku Law," in Hall, Nagahara, and Yamamura (eds.), Japan Before Tokugawa: Political Consolidation and Economic Growth (1981), chapter 3.

- K. A. Grossberg & N. Kanamoto 1981, The Laws of the Muromachi Bakufu: Kemmu Shikimoku (1336) and Muromachi Bakufu Tsuikaho, MN Monographs (Sophia UP)

- Hall, John C. "Japanese Feudal Laws: the Magisterial Code of the Hojo Power Holders (1232) ." Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan 2nd ser. 34 (1906)

- "Japanese Feudal laws: The Ashikaga Code." Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan 1st ser. 36 (1908):

- John Allyn, "Forty-Seven Ronin Story" ISBN 0-8048-0196-7

- Imagawa Ryoshun, The Regulations of Imagawa Ryoshun (1412 A.D.) Imagawa_Ryoshun

- Algernon Bertram Freeman-Mitford, 1st Baron Redesdale, Final_Statement_of_the_47_Ronin (1701 A.D.)

- The Message Of Master Gokurakuji — Hōjō Shigetoki (1198A.D.-1261A.D.) Hojo_shigetoki

- Sunset of the Samurai--The True Story of Saigo Takamori Military History Magazine

- Onoda, Hiroo, No Surrender: My Thirty-Year War. Trans. Charles S. Terry. (New York, Kodansha International Ltd, 1974) ISBN 1-55750-663-9

- An interview with William Scott Wilson about Bushidō

- Bushidō Website: a good definition of bushidō, including The Samurai Creed

- The website of William Scott Wilson Archived 2009-03-05 at the Wayback Machine A 2005 recipient of the Japanese Government's Japan’s Foreign Minister’s Commendation, William Scott Wilson was honored for his research on Samurai and Bushidō.

- Hojo Shigetoki (1198–1261)and His Role in the History of Political and Ethical Ideas in Japan by Carl Steenstrup; Curzon Press (1979)ISBN 0-7007-0132-X

- A History of Law in Japan Until 1868 by Carl Steenstrup; Brill Academic Publishers;second edition (1996) ISBN 90-04-10453-4

- Bushido — The Soul of Japan by Inazo Nitobe (1905) (ISBN 0-8048-3413-X)

- Budoshoshinshu – The Code of The Warrior by Daidōji Yūzan (ISBN 0-89750-096-2)

- Hagakure-The Book of the Samurai By Tsunetomo Yamamoto (ISBN 4-7700-1106-7 paperback, ISBN 4-7700-2916-0 hardcover)

- Go Rin No Sho – Miyamoto Musashi (1645) (ISBN 4-7700-2801-6 hardback, ISBN 4-7700-2844-X hardback Japan only)

- The Unfettered Mind – Writings of the Zen Master to the Sword master by Takuan Sōhō (Musashi's mentor) (ISBN 0-87011-851-X)

- The Religion of the Samurai (1913 original text), by Kaiten Nukariya, 2007 reprint by ELPN Press ISBN 0-9773400-7-4

- Tales of Old Japan by Algernon Bertram Freeman-Mitford (1871) reprinted 1910

- Sakujiro Yokoyama's Account of a Samurai Sword Duel

- Death Before Dishonor By Masaru Fujimoto — Special to The Japan Times: Dec. 15, 2002

- Osprey, "Elite and Warrior Series" Assorted. Archived 2006-03-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Stephen Turnbull, "Samurai Warfare" (London, 1996), Cassell & Co ISBN 1-85409-280-4

- Lee Teng-hui, former President of the Republic of China, "武士道解題 做人的根本 蕭志強譯" in Chinese,前衛, "「武士道」解題―ノーブレス・オブリージュとは" in Japanese,小学館,(2003), ISBN 4-09-387370-4

- Alexander Bennett (2017). Bushido and the Art of Living: An Inquiry into Samurai Values. Tokyo: Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture.