Azad Kashmir

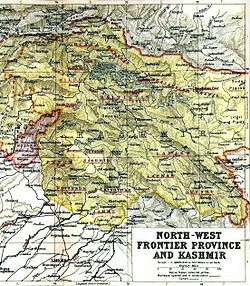

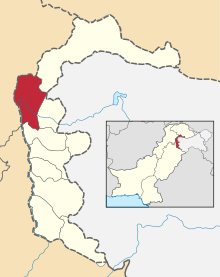

Azad Jammu and Kashmir (Urdu: آزاد جموں و کشمیر, romanized: āzād jammū̃ ō kaśmīr, transl. 'Free Jammu and Kashmir'[2]), abbreviated as AJK and colloquially referred to as simply Azad Kashmir, is a region administered by Pakistan as a nominally self-governing jurisdiction,[1][2] and constituting the western portion of the larger Kashmir region which has been the subject of a dispute between India and Pakistan since 1947.[8] The territory shares a border to the north with Gilgit-Baltistan, together with which it is referred to by the United Nations and other international organizations as "Pakistani-administered Kashmir".[note 1] Azad Kashmir is one-sixth the size of Gilgit-Baltistan and constitutes part of what is Kashmir proper—a valley divided between Indian and Pakistani control in which the majority of the ethnic Kashmiri population lives.[13] Azad Kashmir also shares borders with the Pakistani provinces of Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa to the south and west, respectively. On the eastern side, Azad Jammu and Kashmir is separated from the Indian union territory of Jammu and Kashmir (part of Indian-administered Kashmir) by the Line of Control (LoC), which serves as the de facto border between India and Pakistan in Kashmir. The administrative territory of Azad Jammu and Kashmir (excluding Gilgit-Baltistan) covers a total area of 13,297 km2 (5,134 sq mi), and has a total population of 4,045,366 as per the 2017 national census.

Azad Jammu and Kashmir آزاد جموں و کشمیر | |

|---|---|

Region administered by Pakistan as an administrative territory | |

Sharda, Neelum Valley | |

| |

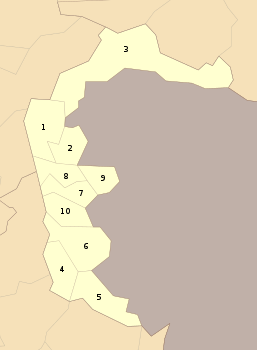

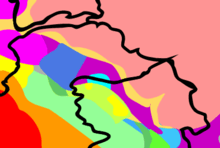

A map of Azad Jammu and Kashmir with individual districts highlighted and labelled. | |

| Coordinates: 33°50′36″N 73°51′05″E | |

| Country | |

| Established | October 24, 1947 (Azad Kashmir Day) |

| Capital | Muzaffarabad |

| Districts | 10 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Self-governing[1][2][3] state under Pakistani administration[4][5] |

| • Body | Government of Azad Kashmir |

| • President | Masood Khan |

| • Prime Minister | Raja Farooq Haider (PML-N) |

| • Chief Secretary | Mathar Niaz Rana[6] |

| • Legislature | Unicameral (49 seats) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 13,297 km2 (5,134 sq mi) |

| Population (2017) | |

| • Total | 4,045,366 |

| • Density | 300/km2 (790/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+05:00 (PST) |

| ISO 3166 code | PK-AJK |

| Languages | |

| HDI (2018) | 0.611 (medium) |

| Divisions | 3 |

| Districts | 10 |

| Tehsils | 33 |

| Union Councils | 182 |

| Website | www |

The territory has a parliamentary form of government modelled after the British Westminster system, with its capital located at Muzaffarabad. The President of AJK is the constitutional head of state, while the Prime Minister, supported by a Council of Ministers, is the chief executive. The unicameral Azad Kashmir Legislative Assembly elects both the Prime Minister and President. The territory has its own Supreme Court and a High Court, while the Government of Pakistan's Ministry of Kashmir Affairs and Gilgit-Baltistan serves as a link between itself and Azad Jammu and Kashmir's government, although the autonomous territory is not represented in the Parliament of Pakistan.

A major earthquake in 2005 killed at least 100,000 people and left another three million people displaced, causing widespread devastation to the region's infrastructure and economy. Since then, with help from the Government of Pakistan and foreign aid, reconstruction of infrastructure is underway. Azad Kashmir's economy largely depends on agriculture, services, tourism, and remittances sent by members of the British Mirpuri community. Nearly 87% of Azad Kashmiri households own farm property and generate a majority of their income by farming,[14] despite the region having the highest rate of school enrolment in Pakistan and a literacy rate of approximately 72%.[15]

Name

Azad Kashmir (Free Kashmir) was the title of a pamphlet issued by the All Jammu and Kashmir Muslim Conference party at its 13th general session held at Poonch in 1945.[16] It is believed to have been a response to the National Conference's Naya Kashmir (New Kashmir) programme.[17] Although some sources state that it was no more than a compilation of various resolutions passed by the party,[18] its intent seems to have been to declare that the Muslim-majority of Jammu and Kashmir were committed to the All-India Muslim League's struggle for a separate homeland of Pakistan,[16] and that the Muslim Conference was their sole representative organization.[17] However, the following year, the party passed an "Azad Kashmir resolution" demanding that Hari Singh, the Hindu Maharaja, to institute a constituent assembly elected on an extended franchise.[19] According to scholar Chitralekha Zutshi, the organization's declared goal was to achieve responsible governance under the aegis of the Maharaja, without associating with either India or Pakistan.[20] The following year, the party workers assembled at the house of Sardar Ibrahim Khan on 19 July 1947 and reversed the decision, demanding that the Maharaja accede his princely state of Jammu and Kashmir to Pakistan.[21][22]

To avoid any potential persecution by the Maharaja's forces, Sardar Ibrahim escaped to Pakistan and directed the Poonch rebellion from there with the assistance of Pakistani Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan and other government officials. Liaquat Ali Khan appointed a committee headed by Mian Iftikharuddin to draft a "declaration of freedom".[23] On 4 October 1947, an Azad Kashmir provisional government was declared in Lahore with Ghulam Nabi Gilkar as President under the assumed name "Mr. Anwar" and Sardar Ibrahim as the Prime Minister. Gilkar travelled to Srinagar and was immediately arrested by the Maharaja's state forces. Pakistani officials subsequently appointed Sardar Ibrahim as the President of Azad Jammu and Kashmir.[24][note 2]

Geography

The northern part of Azad Jammu and Kashmir encompasses the lower area of the Himalayas, including Jamgarh Peak (4,734 m or 15,531 ft). Hari Parbat peak in Neelum Valley is the highest point within the state.[4]

The region receives rainfall in both winter and summer. Throughout most of the region, the average rainfall tends to exceed just around 1400 mm, with the highest average rainfall occurring near Muzaffarabad (around 1800 mm). Thus, Muzaffarabad and its surrounding areas are, on average, among the wettest regions of Pakistan. During summertime, monsoon floods caused by the rivers Jhelum and Leepa are common due to extreme rains and snowmelt.

History

Following the Partition of India in 1947, the British abandoned their suzerainty over the princely states of the British Raj. These kingdoms were left with the options of joining the Dominion of India, Dominion of Pakistan or remaining independent. Hari Singh, the Hindu Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir, wanted his state to remain independent.[26][27] Jammu and Kashmir's Muslim-majority population, especially those in Western Jammu province (roughly correspondent with present-day Azad Kashmir) and the Frontier Districts Province (roughly correspondent with present-day Gilgit-Baltistan) strongly expressed their desire to join Pakistan rather than India (the Dominion that was gaining favour with Hari Singh).[28]

After a period of communal tensions (primarily between the Kashmiri population and Hari Singh's administration), a major rebellion seeking to overthrow the Maharaja's government broke out in June 1947 in Poonch (a district that was later divided, with one half under Indian administration and the other under Pakistani administration), an area that bordered the Rawalpindi Division of West Punjab, British India. The Maharaja is believed to have started levying punitive taxes on the peasantry which provoked the revolt, following which Hari Singh's administration resorted to brutal suppression. The area's population, swelled by recently demobilized soldiers following World War II, rebelled against the Maharaja's state forces and gained control of almost the entire district. Following this victory, the pro-Pakistan chieftains of the western districts of Muzaffarabad, Poonch and Mirpur proclaimed a provisional Azad Jammu and Kashmir government in Rawalpindi on October 3, 1947.[29][note 3] Ghulam Nabi Gilkar, under the assumed name "Mr. Anwar," issued a proclamation in the name of the provisional government in Muzaffarabad. However, this government quickly fizzled out with the arrest of Anwar in Srinagar.[31] On October 21, a second provisional government of Azad Kashmir was established in Pallandri under the leadership of Sardar Ibrahim Khan.[32]

Following these series of events, several thousand Pashtun tribesmen from Pakistan's North-West Frontier Province poured into Jammu and Kashmir to support the rebellion and liberate the region from Hari Singh's rule. These irregular forces were directed by experienced military leaders and were equipped with relatively modern armaments. As the Maharaja lost favour with the Kashmiri population, his crumbling state forces were unable to withstand the onslaught by the Pakistani militias. The raiders swiftly captured the towns of Muzaffarabad and Baramulla, the latter being 32 kilometres (20 mi) northwest of the state's capital, Srinagar. Three days later, the Maharaja recognized that Pakistan's takeover of Jammu and Kashmir was imminent, and requested immediate military assistance from neighbouring India. Indian officials responded to Hari Singh's request by stating that India would only provide military assistance to his government if he signed an Instrument of Accession to merge the entire princely state of Jammu and Kashmir with the Dominion of India. Hari Singh agreed to the condition and signed the Instrument of Accession for Jammu and Kashmir on 26 October 1947, handing over total control of defence, external affairs and communications to the Government of India in return for aid.[33] Indian troops were immediately airlifted into Srinagar and deployed throughout the rest of the princely state to combat the raiders.[34] The Government of Pakistan condemned the "illegal" accession and refused to recognize its legitimacy for a variety of reasons, subsequently deploying Pakistani troops in Jammu and Kashmir to intervene and support the Kashmiri rebels in combatting the Indian Army.[27] The clash between the militaries of India and Pakistan here sparked the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947-48 (also known as the First Kashmir War). Intense fighting ensued between the two sides in Kashmir for just over a year, with the areas of control more or less stabilizing around a United Nations-mandated Ceasefire Line. Subsequently, international UN military observers were deployed to supervise the newly-established line (which served as a de facto border) and mediate between the two nations.[35]

Indian officials maintained that Hari Singh's signing of the Instrument of Accession gave India the grounds to take over Kashmir's sovereignty, whereas Pakistan argued that the Instrument of Accession was fraudulent and Muslim-majority Kashmir should merge with Pakistan through a vote. India later approached the United Nations, asking it to resolve the dispute, and resolutions were passed in favour of holding a plebiscite with regard to Kashmir's future in April 1948. However, no such plebiscite has ever been held on either side, due to the following preconditions:[36]

- The Government of Pakistan's requirement to withdraw all Pakistani troops from Jammu and Kashmir; and immediately ceasing any further support to tribesmen and rebel elements fighting within the state.

- The Government of India's requirement to reduce the Indian military's presence in Kashmir to the bare minimum (e.g. the Jammu and Kashmir State Forces) required to maintain basic law and order.

- India's requirement to appoint a "Plebiscite Administrator" nominated and selected by the United Nations with all the powers required to ensure a "free and impartial" plebiscite and deal with both countries.

The withdrawal that was required of both nations never took place, and UN military observers at what later became the Line of Control (LoC) gradually became subject to severe operative restrictions by both India and Pakistan, who ceased to recognize their jurisdiction in the region.[37]

Following the 1949 ceasefire agreement with India, the Government of Pakistan divided the northern and western parts of Kashmir that it controlled at the time of into the following two separately-controlled political entities:

- Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK) — the narrow, southern part of Pakistani-adminstered Kashmir; approximately 400 km (250 mi) in length, with a width varying from 15 to 65 km (10 to 40 mi).

- Federally Administered Northern Areas (FANA) — the much larger political entity to the north of AJK with an area of 74,871 km2 (28,908 sq mi); the region was later renamed to Gilgit-Baltistan, with an area of 72,971 km2 (28,174 sq mi) following the 1963 Sino-Pakistani Agreement.

The Shaksgam Valley was under Pakistani administration as part of the adminstrative territory of Gilgit-Baltistan until 1963, when the region was provisionally ceded by Pakistan to the People's Republic of China. The tract fell under Chinese administration (as part of China's Xinjiang autonomous region) following the agreement with Pakistan and continues to be disputed by India, which "recognizes the cession [of occupied Indian land] as illegal."

India and Pakistan held a meeting in 1972 to iron out the status of the 1949 UN-mandated Ceasefire Line. Both parties signed the 1972 Shimla Agreement, which maintained that the Ceasefire Line (officially designated by both countries as the "Line of Control (LoC)") would continue to serve as the de facto border between the two countries in the Kashmir region until the dispute is settled.[38] Some political experts claim that, in view of the 1972 pact, the only solution to the India-Pakistan issue is mutual negotiation between the two countries without involving a third party such as the United Nations. Following this, the 1974 Interim Constitution Act was passed by the 48-member Azad Jammu and Kashmir unicameral assembly.[39]

Government

Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK) is a self-governing state under Pakistani control, but under Pakistan's constitution, the state is informally part of the country. Pakistan is administering the region as a self-governing territory rather than incorporating it in the federation since the UN-mandated ceasefire.[4][40] Azad Kashmir has its own elected President, Prime Minister, Legislative Assembly, High Court, with Azam Khan as its present chief justice, and official flag.[41]

Azad Kashmir's financial matters, i.e., budget and tax affairs, are dealt with by the Azad Jammu and Kashmir Council rather than by Pakistan's Central Board of Revenue. The Azad Jammu and Kashmir Council is a supreme body consisting of 14 members, 8 from the government of Azad Jammu and Kashmir and 6 from the government of Pakistan. Its chairman/chief executive is the prime minister of Pakistan. Other members of the council are the president and the prime minister of Azad Kashmir (or and individual nominated by her/him) and 6 members of the AJK Legislative Assembly.[41][40] Azad Kashmir Day is celebrated in Azad Jammu and Kashmir on October 24, which is the day that the Azad Jammu and Kashmir government was created in 1947. Pakistan has celebrated Kashmir Solidarity Day on February 5 of each year since 1990 as a day of protest against India's de facto sovereignty over its State of Jammu and Kashmir.[42] That day is a national holiday in Pakistan.[43] Kashmiris in Azad Kashmir observe the Kashmir Black Day on October 27 of each year since 1947 as a day of protest against military occupation in Indian controlled Jammu and Kashmir.

Brad Adams the Asia director at the U.S.-based NGO Human Rights Watch has said in 2006; "Although 'azad' means 'free,' the residents of Azad Kashmir are anything but, the Pakistani authorities govern Azad Kashmir government with tight controls on basic freedoms."[44] Scholar Christopher Snedden has observed that despite tight controls the people of Azad Kashmir have generally accepted whatever Pakistan has done to them, which in any case has varied little from how most Pakistanis have been treated (by Pakistan). According to Christopher Snedden, one of the reasons for this was that the people of Azad Kashmir had always wanted to be a part of Pakistan.[45]

Consequently, having little to fear from a pro-Pakistan population devoid of options,[45] Pakistan imposed its will through the Federal Ministry of Kashmir Affairs and failed to empower the people of Azad Kashmir, allowing genuine self-government for only a short period in the 1970s. The Interim Constitution of the 1970s only allows the political parties that pay allegiance to Pakistan: "No person or political party in Azad Jammu and Kashmir shall be permitted... activities prejudicial or detrimental to the State's accession to Pakistan."[45] The pro-independence Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front has never been allowed to contest elections in Azad Kashmir.[46] While the Interim Constitution does not give them a choice, the people of Azad Kashmir have not considered any option other than joining Pakistan.[45] Except in the legal sense, Azad Kashmir has been fully integrated into Pakistan.[45]

Development

According to the project report by the Asian Development Bank, the bank has set out development goals for Azad Kashmir in the areas of health, education, nutrition, and social development. The whole project is estimated to cost US$76 million.[47] Germany, between 2006 and 2014, has also donated $38 million towards the AJK Health Infrastructure Programme.[48]

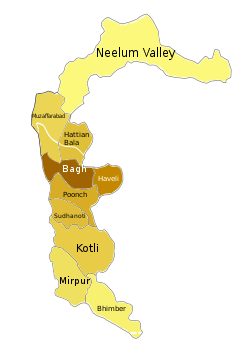

Administrative divisions

The state is administratively divided into three divisions which, in turn, are divided into ten districts.[49]

| Division | District | Area (km2) | Population (2017 Census) | Headquarters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mirpur | Mirpur | 1,010 | 456,200 | New Mirpur City |

| Kotli | 1,862 | 774,194 | Kotli | |

| Bhimber | 1,516 | 420,624 | Bhimber | |

| Muzaffarabad | Muzaffarabad | 1,642 | 650,370 | Muzaffarabad |

| Hattian | 854 | 230,529 | Hattian Bala | |

| Neelam Valley | 3,621 | 191,251 | Athmuqam | |

| Poonch | Poonch | 855 | 500,571 | Rawalakot |

| Haveli | 600 | 152,124 | Forward Kahuta | |

| Bagh | 768 | 371,919 | Bagh | |

| Sudhanoti | 569 | 297,584 | Palandri | |

| Total | 10 districts | 13,297 | 4,045,366 | Muzaffarabad |

Climate

The southern parts of Azad Kashmir including Bhimber, Mirpur and Kotli districts has extremely hot weather in summers and moderate cold weather in winters. It receives rains mostly in monsoon weather.

In the central and northern parts of state weather remains moderate hot in summers and very cold and chilly in winter. Snow fall also occurs there in December and January.

This region receives rainfall in both winters and summers. Muzaffarabad and Pattan are among the wettest areas of the state. Throughout most of the region, the average rainfall exceeds 1400 mm, with the highest average rainfall occurring near Muzaffarabad (around 1800 mm). During summer, monsoon floods of the Jhelum and Leepa rivers are common, due to high rainfall and melting snow.

Population

The population of Azad Kashmir, according to the preliminary results of the 2017 Census, is 4.45 million.[50] The website of the AJK government reports the literacy rate to be 74%, with the enrolment rate in primary school being 98% and 90% for boys and girls respectively.[51]

The population of Azad Kashmir is almost entirely Muslim. The people of this region culturally differ from the Kashmiris living in the Kashmir Valley of Jammu and Kashmir, and are closer to the culture of Jammu. Mirpur, Kotli and Bhimber are all old towns of the Jammu region.[52]

Religion

Azad Jammu and Kashmir has an almost entirely Muslim population. According to a data maintained by Christian community organizations, there are around 4,500 Christian residents in the region. Bhimber is home to most of them, followed by Mirpur and Muzaffarabad. A few dozen families also live in Kotli, Poonch and Bagh. However, the Christian community has been struggling to get residential status and property rights in AJK. There is no official data on the total number of Bahais in AJK. Only six families are known to be living in Muzaffarabad while some of them live in rural areas. The followers of the Ahmadi faith is estimated to be somewhere between 20,000 and 25,000 and most of them live in Kotli, Mirpur Bhimber and Muzaffarabad.[53]

Ethnic groups

Most residents of the region are not ethnic Kashmiris.[54] Rather the majority in Azad Kashmir are ethnically related to Punjabis.[55][56]

The main communities living in this region are:[57]

- Gujjars – They are an agricultural tribe and are estimated to be the largest community living in ten districts of Azad Kashmir.[57][58][59]

- Sudhans – (also known as Sadozai, Sardar) are second largest tribe mainly living the districts of Poonch, Sudhanoti, Bagh and Kotli in Azad Kashmir, allegedly originating from Pashtun areas.[60][57][58] Together with the Rajputs, they are the source of most of Azad Kashmir's political leaders.[61]

- Jats – They are one of the larger community of AJK and primarily inhabit the Districts of Mirpur, Bhimber and Kotli. A large Mirpuris population lives in the UK and it is estimated that more people of Mirpuri origins are now residing in the UK than in Mirpur district. The district Mirpur retains strong ties with the UK.[57][62]

- Rajputs – They are spread across the territory, and they number little under half a million. Together with the Sundhans, they are the source of most of Azad Kashmir's political class.[61]

- Mughals – Largely located in Bagh and Muzaffarabad districts.[59]

- Awans – A clan with significant numbers found in Azad Jammu and Kashmir, living mainly in the Bagh, Poonch, Hattian Bala and Muzaffarabad. Besides Azad Kashmir they also reside in Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in large numbers.[57][58][59]

- Abbasis – They are a large clan in Azad Jammu and Kashmir and mostly live in Bagh, Hattian Bala and Muzaffarabad districts. Besides Azad Kashmir, they also inhabit, Abbottabad and upper Potohar Punjab in large numbers.[57][58][59]

- Kashmiris – Ethnic Kashmiri populations are found in Neelam Valley and Leepa Valley.[63]

The culture of Azad Kashmir has many similarities to that of northern Punjabi (Potohar) culture in Punjab province, while the Sudhans have oral tradition of Pashtuns. The Peshawari turban is worn by some Sudhans in the area.

The traditional dress of the women is the shalwar kameez in Pahari style. The shalwar kameez is commonly worn by both men and women. Women use shawl to cover their head and upper body.

Languages

The official language of Azad Kashmir is Urdu,[64][note 4] while English is used in higher domains. The majority of the population, however, are native speakers of other languages. The foremost among these is Pahari–Pothwari, with its various dialects. There are also sizeable communities speaking Gujari and Kashmiri, as well as pockets of speakers of Shina, Pashto and Kundal Shahi. With the exception of Pashto and English, these languages belong to the Indo-Aryan language family.

The dialects of the Pahari-Pothwari language complex cover most of the territory of Azad Kashmir. These are also spoken across the Line of Control in neighbouring areas of Indian Jammu and Kashmir, and are closely related both to Punjabi to the south and Hinko to the northwest. The language variety in the southern districts of Azad Kashmir is known by a variety of names – including Mirpuri, Pothwari and Pahari – and is closely related to the Pothwari proper spoken to the east in the Pothohar region of Punjab. The dialects of the central districts of Azad Kashmir are occasionally referred to in the literature as Chibhali or Punchi, but the speakers themselves usually call them Pahari, an ambiguous name that is also used for several unrelated languages of the Lower Himalayas. Going north, the speech forms gradually change into Hindko. Already in Muzaffarabad District the preferred local name for the language is Hindko, although it is still apparently more closely related to the core dialects of Pahari.[65] Further north in the Neelam Valley the dialect, locally also known as Parmi, can more unambiguously be subsumed under Hindko.[66]

Another major language of Azad Kashmir is Gujari. It is spoken by several hundred thousand[note 5] people among the traditionally nomadic Gujars, many of whom are nowadays settled. Not all ethnic Gujars speak Gujari, the proportion of those who have shifted to other languages is probably higher in southern Azad Kashmir.[67] Gujari is most closely related to the Rajasthani languages (particularly Mewati), although it also shares features with Punjabi.[68] It is dispersed over large areas in northern Pakistan and India. Within Pakistan, the Gujari dialects of Azad Kashmir are more similar, in terms of shared basic vocabulary and mutual intelligibility, to the Gujar varieties of the neighbouring Hazara region than to the dialects spoken further to the northwest in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and north in Gilgit.[69]

There are scattered communities of Kashmiri speakers,[70] notably in the Neelam Valley, where they form the second-largest language group after speakers of Hindko.[71] There have been calls for the teaching of Kashmiri (particularly in order to counter India's claim of promoting the culture of Kashmir), but the limited attempts at introducing the language at the secondary school level have not been successful, and it is Urdu, rather than Kashmiri, that Kashmiri Muslims have seen as their identity symbol.[72] There is an ongoing process of gradual shift to larger local languages,[64] but at least in the Neelam Valley there still exist communities for whom Kashmiri is the sole mother tongue.[73]

In the northernmost district of Neelam, there are pockets of other languages. Shina, which like Kashmiri belongs to the Dardic group, is present in two distinct varieties spoken altogether in three villages. The Iranian language Pashto, the major language of the neighbouring province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, is spoken in two villages in Azad Kashmir, both situated on the Line of Control. The endangered Kundal Shahi is native to the eponymous village and it is the only language not found outside Azad Kashmir.[74]

Economy

Historically the economy of Azad Kashmir has been agricultural which meant that land was the main source or mean of production. This means that all food for immediate and long term consumption was produced from land. The produce included various crops, fruits, vegetables, etc. Land was also the source of other livelihood necessities such as wood, fuel, grazing for animals which then turned into dairy products. Because of this land was also the main source of revenue for the governments whose primary purpose for centuries was to accumulate revenue.[75]

Agriculture is a major part of Azad Kashmir's economy. Low-lying areas that have high populations grow crops like barley, mangoes, millet, corn (maize), and wheat, and also raise cattle. In the elevated areas that are less populated and more spread-out, forestry, corn, and livestock are the main sources of income. There are mineral and marble resources in Azad Kashmir close to Mirpur and Muzaffarabad. There are also graphite deposits at Mohriwali. There are also reservoirs of low-grade coal, chalk, bauxite, and zircon. Local household industries produce carved wooden objects, textiles, and dhurrie carpets.[4] There is also an arts and crafts industry that produces such cultural goods as namdas, shawls, pashmina, pherans, Papier-mâché, basketry copper, rugs, wood carving, silk and woolen clothing, patto, carpets, namda gubba, and silverware. Agricultural goods produced in the region include mushrooms, honey, walnuts, apples, cherries, medicinal herbs and plants, resin, deodar, kail, chir, fir, maple, and ash timber.[4][40][76]

The migration to UK was accelerated and by the completion of Mangla Dam in 1967 the process of 'chain migration' became in full flow. Today, remittances from British Mirpuri community make a critical role in AJK's economy. In the mid-1950s various economic and social development processes were launched in Azad Kashmir. In the 1960s, with the construction of the Mangla Dam in Mirpur District, the Azad Jammu and Kashmir Government began to receive royalties from the Pakistani government for the electricity that the dam provided to Pakistan. During the mid-2000s, a multibillion-dollar reconstruction began in the aftermath of the 2005 Kashmir earthquake.[77]

In addition to agriculture, textiles, and arts and crafts, remittances have played a major role in the economy of Azad Kashmir. One analyst estimated that the figure for Azad Kashmir was 25.1% in 2001. With regard to annual household income, people living in the higher areas are more dependent on remittances than are those living in the lower areas.[78] In the latter part of 2006, billions of dollars for development were mooted by international aid agencies for the reconstruction and rehabilitation of earthquake-hit zones in Azad Kashmir, though much of that amount was subsequently lost in bureaucratic channels, leading to considerable delays in help getting to the most neediest. Hundreds of people continued to live in tents long after the earthquake.[77] A land-use plan for the city of Muzaffarabad was prepared by the Japan International Cooperation Agency.

Tourist destinations in the area include the following:

- Muzaffarabad, the capital city of Azad Kashmir, is located on the banks of the Jhelum and Neelum rivers. It is 138 km (86 mi) from Rawalpindi and Islamabad. Well-known tourist spots near Muzaffarabad are the Red Fort, Pir Chinassi, Patika, Subri Lake and Awan Patti.

- The Neelam Valley is situated to the north and northeast of Muzaffarabad, The gateway to the valley. The main tourist attractions in the valley are Athmuqam, Kutton, Keran, Changan, Sharda, Kel, Arang Kel and Taobat.

- Sudhanoti is one of the eight districts of Azad Kashmir in Pakistan. Sudhanoti is located 90 km (56 mi) away from Islamabad, the Capital of Pakistan. It is connected with Rawalpindi and Islamabad through Azad Pattan road.

- Rawalakot city is the headquarters of Poonch District and is located 122 km (76 mi) from Islamabad. Tourist attractions in Poonch District are Banjosa Lake, Devi Gali, Tatta Pani, and Toli Pir.

- Bagh city, the headquarters of Bagh District, is 205 km (127 mi) from Islamabad and 100 km (62 mi) from Muzaffarabad. The principal tourist attractions in Bagh District are Bagh Fort, Dhirkot, Sudhan Gali, Ganga Lake, Ganga Choti, Kotla Waterfall, Neela Butt, Danna, Panjal Mastan National Park, and Las Danna.

- The Leepa Valley is located 105 km (65 mi) southeast of Muzaffarabad. It is the most charming and scenic place for tourists in Azad Kashmir.

- New Mirpur City is the headquarters of Mirpur District. The main tourist attractions near New Mirpur City are the Mangla Lake and Ramkot Fort.

Education

.jpg)

The literacy rate in Azad Kashmir was 62% in 2004, higher than in any other region of Pakistan.[79] However, only 2.2% were graduates, compared to the average of 2.9% for Pakistan.[80]

Universities

The following is a list of universities recognised by Higher Education Commission of Pakistan (HEC):[81]

| University | Location(s) | Established | Type | Specialization | Website |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mirpur University of Science and Technology, Mirpur | Mirpur | 1980 (2008)* | Public | Engineering & Technology | |

| University of Azad Jammu and Kashmir | Muzaffarabad | 1980 | Public | General | |

| University of Azad Jammu and Kashmir (Neelam Campus) | Neelum | 2013 | Public | General | |

| University of Azad Jammu and Kashmir (Jhelum Valley Campus) | Jhelum Valley District | 2013 | Public | General | |

| Al-Khair University | Mirpur | 1994 (2011*) | Private | General | |

| Mohi-ud-Din Islamic University | Nerian Sharif | 2000 | Private | General | |

| University of Poonch (Rawlakot Campus) | Rawalakot | 1980 (2012)* | Public | General | |

| University of Poonch ( SM Campus, Mong, Sudhnoti District) | Sudhnoti District | 2014 | Public | General | |

| University of Poonch ( Kahuta Campus, Haveli District) | Haveli District | 2015 | Public | General | |

| Women University of Azad Jammu and Kashmir Bagh | Bagh | 2013 | Public | General | |

| University of Management Sciences and Information Technology | Kotli | 2014 | Public | General | |

| Mirpur University of Science and Technology ( Bhimber Campus) | Bhimber | 2013 | Public | Science & Humanities |

* Granted university status.

Cadet College Pallandri

- Cadet College Palandri is situated about 100 km (62 mi) from Islamabad

Medical colleges

The following is a list of undergraduate medical institutions recognised by Pakistan Medical and Dental Council (PMDC) as of 2013.[82]

Private medical colleges

- Mohi-ud-Din Islamic Medical College in Mirpur

Sports

Football, cricket and volleyball are very popular in Azad Kashmir. Many tournaments are also held throughout the year and in the holy month of Ramazan, night-time flood-lit tournaments are also organised.

Azad Kashmir has a T20 cricket team in Pakistan's T20 domestic tournament

New Mirpur City has a cricket stadium (Quaid-e-Azam Stadium) which has been taken over by the Pakistan Cricket Board for renovation to bring it up to International standards. There is also a cricket stadium in Muzaffarabad with the capacity of 8,000 people. This stadium has hosted 8 matches of Inter-District Under 19 Tournament 2013.

There are also registered football clubs:

- Pilot Football Club

- Youth Football Club

- Kashmir National FC

- Azad Super FC

Tourism

See also

- 1941 Census of Jammu and Kashmir

- Kashmir conflict

- Tourism in Azad Kashmir

- List of cultural heritage sites in Azad Kashmir

Notes

- The Indian government and Indian sources refer to Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan as "Pakistan-occupied Kashmir" ("PoK")[9] or "Pakistan-held Kashmir" (PHK).[10] Sometimes Azad Kashmir alone is meant by these terms.[9] "Pakistan-administered Kashmir" and "Pakistan-controlled Kashmir"[11][12] are used by neutral sources. Conversely, Pakistani sources call the territory under Indian control "Indian-Occupied Kashmir" ("IOK") or "Indian-Held Kashmir" ("IHK").[9]

- The official with direct involvement in the affair was the Commissioner of Rawalpindi Division, Khawaja Abdul Rahim. He was assisted by Nasim Jahan, the wife of Colonel Akbar Khan.[25]

- Officially, Mirpur and Poonch districts were in the Jammu province of the state and Muzaffarabad was in the Kashmir province. All three provinces spoke languages related to Punjabi, not the Kashmiri language spoken in the Kashmir Valley.[30]

- Snedden (2013, p. 176): On p. 29, the census report states that Urdu is the official language of the Government of Azad Kashmir, with Kashmiri, Pahari, Gojri, Punjabi, Kohistani, Pushto and Sheena 'frequently spoken in Azad Kashmir'. Yet, when surveyed about their 'Mother Tongue', Azad Kashmiris' choices were limited to selecting from Pakistan's major languages: Urdu, Punjabi, Sindhi, Pushto, Balochi, Saraiki and 'Others'; not surprisingly, 2.18 million of Azad Kashmir's 2.97 million people chose 'Others'.

- Hallberg & O'Leary (1992, p. 96) report two rough estimates for the total population of Gujari speakes in Azad Kashmir: 200,000 and 700,000, both from the 1980s.

References

- Bird, Richard M.; Vaillancourt, François (December 4, 2008). Fiscal Decentralization in Developing Countries. Cambridge University Press. pp. 127–. ISBN 978-0-521-10158-5.

- Bose, Sumantra (2009). Contested Lands. Harvard University Press. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-674-02856-2.

Azad Kashmir – 'Free Kashmir,' the more populated and nominally self-governing part of Pakistani-controlled Kashmir

- "Territorial limits". Herald. May 7, 2015. Archived from the original on July 25, 2015. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

These are self-ruled autonomous regions. But restrictions apply.

- "Azad Kashmir". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- "Kashmir profile". BBC News. November 26, 2014. Archived from the original on July 16, 2015. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

- https://cs.ajk.gov.pk/

- "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- The application of the term "administered" to the various regions of Kashmir and a mention of the Kashmir dispute is supported by the tertiary sources (a) and (b), reflecting due weight in the coverage:

(a) "Kashmir, region Indian subcontinent", Encyclopædia Britannica, retrieved August 15, 2019 (subscription required) Quote: "Kashmir, region of the northwestern Indian subcontinent ... has been the subject of dispute between India and Pakistan since the partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947. The northern and western portions are administered by Pakistan and comprise three areas: Azad Kashmir, Gilgit, and Baltistan, the last two being part of a territory called the Northern Areas. Administered by India are the southern and southeastern portions, which constitute the state of Jammu and Kashmir but are slated to be split into two union territories. China became active in the eastern area of Kashmir in the 1950s and has controlled the northeastern part of Ladakh (the easternmost portion of the region) since 1962.";

(b) "Kashmir", Encyclopedia Americana, Scholastic Library Publishing, 2006, p. 328, ISBN 978-0-7172-0139-6 C. E Bosworth, University of Manchester Quote: "KASHMIR, kash'mer, the northernmost region of the Indian subcontinent, administered partlv by India, partly by Pakistan, and partly by China. The region has been the subject of a bitter dispute between India and Pakistan since they became independent in 1947"; - Snedden 2013, pp. 2–3.

- Chandra, Bipan; Mukherjee, Aditya; Mukherje, Mridula (2008). India since Independence. Penguin Books India. p. 416. ISBN 978-0143104094.

- Bose, Sumantra (2009). Contested lands: Israel-Palestine, Kashmir, Bosnia, Cyprus and Sri Lanka. Harvard University Press. p. 193. ISBN 978-0674028562.

- Behera, Navnita Chadha (2007). Demystifying Kashmir. Pearson Education India. p. 66. ISBN 978-8131708460.

- "Gilgit-Baltistan: Story of how region 6 times the size of PoK passed on to Pakistan".

- "Underdevelopment in AJK". The News International. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- "Education emergency: AJK leading in enrolment, lagging in quality – The Express Tribune". The Express Tribune. March 26, 2013. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- Behera, Demystifying Kashmir (2007), p. 20.

- Kapoor, Politics of Protests in Jammu and Kashmir (2014), Chapter 6, p. 273.

- Ganai, Dogra Raj and the Struggle for Freedom in Kashmir (1999), Chapter 6, p. 341.

- Saraf, Kashmiris Fight for Freedom, Volume 1, 2015 & p-663.

- Zutshi, Chitralekha (2004), Languages of Belonging: Islam, Regional Identity, and the Making of Kashmir, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, p. 302, ISBN 978-1-85065-700-2

- Saraf, Kashmiris Fight for Freedom, Volume 2 (2015), p. 9.

- Puri, Balraj (November 2010), "The Question of Accession", Epilogue, 4 (11): 5

- Saraf, Kashmiris Fight for Freedom, Volume 2 2015, pp. 148–149.

- Saraf, Kashmiris Fight for Freedom, Volume 2 (2015), p. 547.

- Saraf, Kashmiris Fight for Freedom, Volume 2 (2015), p. 547.

- "The J&K conflict: A Chronological Introduction". India Together. Retrieved June 5, 2010.

- Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. "Kashmir (region, Indian subcontinent) – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved June 5, 2010.

- Snedden, Christopher (2013). Kashmir-The Untold Story. HarperCollins Publishers India. p. 14. ISBN 978-93-5029-898-5 – via Google Books.

Similarly, Muslims in Western Jammu Province, particularly in Poonch, many of whom had martial capabilities, and Muslims in the Frontier Districts Province strongly wanted J&K to join Pakistan.

- Bose 2003, pp. 32–33.

- Behera, Navnita Chadha (2007), Demystifying Kashmir, Pearson Education India, p. 29, ISBN 978-8131708460

- Snedden 2013, p. 59.

- Snedden 2013, p. 61.

- "Kashmir: Why India and Pakistan fight over it". BBC News. November 23, 2016.

- Bose 2003, pp. 35–36.

- Prem Shankar Jha. "Grasping the Nettle". South Asian Journal. Archived from the original on May 16, 2010.

- "UN resolution 47". Retrieved September 11, 2012.

- "UNCIP Resolution of August 13, 1948 (S/1100) – Embassy of India, Washington, D.C." Archived from the original on October 13, 2007.

- "UNMOGIP: United Nations Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan". Archived from the original on May 14, 2008.

- "How free is Azad Kashsmir". The Indian Express. March 26, 2016.

- "Azad Jammu and Kashmir – Introduction". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved June 22, 2010.

- "AJ&K Portal". ajk.gov.pk.

- "Pakistan to observe Kashmir Solidarity Day today". The Hindu. February 5, 2007. Retrieved February 5, 2008.

- "Kashmir Day being observed today". The News International. February 5, 2008. Retrieved February 5, 2008.

- Adams, Brad (September 22, 2006). "Pakistan: 'Free Kashmir' Far From Free". Human Rights Watch.

- Snedden, Christopher (2013). Kashmir-The Untold Story. Harper Collins Publishers India. p. 93. ISBN 978-93-5029-898-5.

Second, Azad Kashmiris had always wanted to be part of this nation.

- Bose, Sumantra (2003), Kashmir: Roots of Conflict, Paths to Peace, Harvard University Press, p. 100, ISBN 0-674-01173-2

- "Report and Recommendation of the President to the Board of Directors on a Proposed Loan to the Islamic Republic of Pakistan for the Multisector Rehabilitation and Improvement Project for Azad Jammu and Kashmir" (PDF). Asian Development Bank. November 2004. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- "Pakistan Donor Profile and Mapping" (PDF). United Nations in Pakistan. August 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 15, 2017. Retrieved February 5, 2017.

- "Administrative Setup". ajk.gov.pk. Archived from the original on April 9, 2010. Retrieved May 17, 2010.

- "Census 2017: AJK population rises to over 4m". The Nation. August 26, 2017. Retrieved June 10, 2018.

- "AJ&K at a Glance". Retrieved June 10, 2018.

- With Friends Like These... (Report). 18. Human Rights Watch. September 2006. Retrieved November 24, 2013.

- "The Plight of Minorities in 'Azad Kashmir'". Asianlite.com. January 14, 2019. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- Snedden, Christopher (2015). Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris. Oxford University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-84904-622-0.

Confusingly, the term 'Kashmiri' also has wider connotations and uses. Some people in Azad Kashmir call themselves 'Kashmiris'. This is despite most Azad Kashmiris not being of Kashmiri ethnicity.

- Kennedy, Charles H. (August 2, 2004). "Pakistan: Ethnic Diversity and Colonial Legacy". In John Coakley (ed.). The Territorial Management of Ethnic Conflict. Routledge. p. 153. ISBN 9781135764425.

- Ballard, Roger (March 2, 1991), "Kashmir Crisis: View from Mirpur" (PDF), Economic and Political Weekly, 26 (9/10): 513–517, JSTOR 4397403, archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016, retrieved July 19, 2020,

... they are best seen as forming the eastern and northern limits of the Potohari Punjabi culture which is otherwise characteristic of the upland parts of Rawalpindi and Jhelum Districts

- Snedden 2013, Role of Biradaries (pp. 128–133)

- "District Profile - Rawalakot/Poonch" (PDF). Earthquake Reconstruction and Rehabilitation Authority. July 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- "District Profile - Bagh" (PDF). Earthquake Reconstruction and Rehabilitation Authority. June 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- Snedden, Christopher (2012). The Untold Story of the People of Azad Kashmir. Columbia University Press. p. xix. ISBN 9780231800204.

Sudhan/Sudhozai – one of the main tribes of (southern) Poonch, allegedly originating from Pashtun areas.

- ""With Friends Like These...": Human Rights Violations in Azad Kashmir: II. Background". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved June 14, 2019.

- Moss, Paul (November 30, 2006). "South Asia | The limits to integration". BBC News. Retrieved June 5, 2010.

- Snedden, Christopher (2015). Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris. Oxford University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-84904-622-0.

- Rahman 1996, p. 226.

- The preceding paragraph is mostly based on Lothers & Lothers (2010). For further references, see the bibliography in Pahari-Pothwari.

- Akhtar & Rehman 2007, p. 68. The conclusion is based on lexical similarity and the comparison is with the Hindko of the Kaghan Valley and with the Pahari of the Murre Hills.

- Hallberg & O'Leary 1992, pp. 96, 98, 100.

- Hallberg & O'Leary 1992, pp. 93–94.

- Hallberg & O'Leary 1992, pp. 111–12, 126.

- Rahman 2002, p. 449; Rahman 1996, p. 226

- Akhtar & Rehman 2007, p. 70.

- Rahman 1996, p. 226; Rahman 2002, pp. 449–50. The discussion in both cases is in the broader context of Pakistan.

- Akhtar & Rehman 2007, pp. 70, 75.

- Akhtar & Rehman 2007.

- "History of Planning & Development Department in AJK". Archived from the original on April 11, 2010.

- "Azad Jammu & Kashmir – Tourism". Archived from the original on May 29, 2008. Retrieved June 22, 2010.

- Naqash, Tariq (October 1, 2006). "'Rs1.25 trillion to be spent in Azad Kashmir': Reconstruction in quake-hit zone". Dawn. Muzaffarabad.

- Suleri, Abid Qaiyum; Savage, Kevin. "Remittances in crises: a case study from Pakistan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 22, 2007. Retrieved June 5, 2010.

- "Literacy Rate in Azad Kashmir nearly 62 pc". Pakistan Times. MUZAFFARABAD (Azad Kashmir). September 27, 2004. Archived from the original on February 27, 2005.

-

Hasan, Khalid (April 17, 2005). "Washington conference studies educational crisis in Pakistan". Daily Times. Washington. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011.

Grace Clark told the conference that only 2.9% of Pakistanis had access to higher education.

- "Our Institutions". Higher Education Commission of Pakistan. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved November 19, 2013.

- "Recognized medical colleges in Pakistan". Pakistan Medical and Dental Council. Archived from the original on August 19, 2010. Retrieved November 19, 2013.

- Sources

- Akhtar, Raja Nasim; Rehman, Khawaja A. (2007). "The Languages of the Neelam Valley". Kashmir Journal of Language Research. 10 (1): 65–84. ISSN 1028-6640.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Behera, Navnita Chadha (2007), Demystifying Kashmir, Pearson Education India, ISBN 8131708462

- Bose, Sumantra (2003). Kashmir: Roots of Conflict, Paths to Peace. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01173-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ganai, Yousuf (1999), Dogra Raj and the Struggle for Freedom in Kashmir, University of Kashmir/Shodhganga

- Hallberg, Calinda E.; O'Leary, Clare F. (1992). "Dialect Variation and Multilingualism among Gujars of Pakistan". In O'Leary, Clare F.; Rensch, Calvin R.; Hallberg, Calinda E. (eds.). Hindko and Gujari. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan. Islamabad: National Institute of Pakistan Studies, Quaid-i-Azam University and Summer Institute of Linguistics. pp. 91–196. ISBN 969-8023-13-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kapoor, Sindhu (2014), Politics of Protests in Jammu and Kashmir from 1925 to 1951, University of Jammu/Shodhganga

- Lothers, Michael; Lothers, Laura (2010). Pahari and Pothwari: a sociolinguistic survey (Report). SIL Electronic Survey Reports. 2010-012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rahman, Tariq (1996). Language and politics in Pakistan. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-577692-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rahman, Tariq (2002). Language, ideology and power : language learning among the Muslims of Pakistan and North India. Karachi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-579644-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Saraf, Muhammad Yusuf (2015) [first published 1977 by Ferozsons], Kashmiris Fight for Freedom, Volume 1, Mirpur: National Institute Kashmir Studies

- Saraf, Muhammad Yusuf (1977), Kashmiris Fight for Freedom, Volume 1, Ferozsons

- Saraf, Muhammad Yusuf (2015) [first published 1979 by Ferozsons], Kashmiris Fight for Freedom, Volume 2, Mirpur: National Institute Kashmir Studies

- Snedden, Christopher (2013) [first published as The Untold Story of the People of Azad Kashmir, 2012]. Kashmir: The Unwritten History. HarperCollins India. ISBN 978-9350298985.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Mathur, Shubh (2008). "Srinagar-Muzaffarabad-New York: A Kashmiri Family's Exile". In Roy, Anjali Gera; Bhatia, Nandi (eds.). Partitioned Lives: Narratives of Home, Displacement and Resettlement. Pearson Education India. ISBN 978-9332506206.

- Schoefield, Victoria (2003) [First published in 2000]. Kashmir in Conflict. London and New York: I. B. Taurus & Co. ISBN 1860648983.

External links

- http://www.ajk.gov.pk/ Government of Azad Jammu and Kashmir

- http://pndajk.gov.pk/ AJ&K Planning and Development Department

- https://ajktourism.gov.pk/ Tourism in Azad Kashmir