Anti-Germans (political current)

Anti-German (German: Antideutsch) is the generic name applied to a variety of theoretical and political tendencies within the radical left mainly in Germany and Austria. The Anti-Germans form one of the main camps within the broader Antifa movement, alongside the Anti-Zionist anti-imperialists, after the two currents split between the 1990s and the early 2000s as a result of their diverging views on Israel.[2] In 2006 Deutsche Welle estimated the number of anti-Germans at between 500 and 3,000.[3]

The basic standpoint of the anti-Germans includes opposition to German nationalism, a critique of mainstream left anti-capitalist views, which are thought to be simplistic and structurally anti-Semitic,[4] and a critique of anti-Semitism, which is considered to be deeply rooted in German cultural history. As a result of this analysis of anti-semitism, support for Israel and opposition to Anti-Zionism is a primary unifying factor of the anti-German movement.[5] The critical theory of Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer is often cited by anti-German theorists.[4]:2

The term does not generally refer to any one specific radical left tendency, but rather a wide variety of distinct currents, ranging from the so-called "hardcore" anti-Germans such as the quarterly journal Bahamas to "softcore" anti-Germans such as the radical left journal Phase 2. Some anti-German ideas have also exerted an influence on the broader radical leftist milieu, such as the monthly magazine konkret and the weekly newspaper Jungle World.

Emergence

The rapid collapse of the German Democratic Republic and the looming reunification of Germany triggered a major crisis within the German Left. The Anti-German tendency first developed in a discussion group known as the Radical Left, which consisted of elements of the German Green Party, Trotskyists, members of the Communist League (Kommunistischer Bund), the journal konkret, and members of Autonome, Libertarian and Anarchist groups, who rejected plans by other segments of Leftist political organisations to join a governing coalition.[6] This circle adopted a position developed by the Kommunistischer Bund, a decidedly pessimistic analysis with regard to the potential for revolutionary change in Germany. Known as the "Fascisation" analysis, this theory held that due to the particularity of German history and development, the endemic crisis of capitalism would lead to a move towards the far right and to a new Fascism.[7]:11

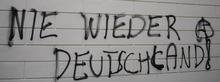

During an internal debate, representatives of the majority tendency said that the minority current, due to its bleak analysis and unwavering pessimism, "might as well just emigrate to the Bahamas."[8] The minority tendency, in an ironic gesture, thus named their discussion organ Bahamas.[8] In 2007 Haaretz described Bahamas as "the leading publication of the hardcore pro-Israel, anti-German communist movement."[8] The phrase Nie wieder Deutschland ("Germany, Never Again"), which became a central anti-German slogan, originated in demonstrations against reunification,[3][8][9][10] the largest of which attracted a crowd of approximately 10,000 people.[7] This early alliance dissipated shortly after the process of reunification was complete.[6]

Development in the 1990s

The notion of a revival of German nationalism and racism as a result of the reunification seemed to confirm itself over the course of the 1990s, as shown by such events as the Rostock-Lichtenhagen riots and a murderous attack on a Turkish family in the West German town of Solingen.[11] Amid this wave of anti-immigrant violence, the German political establishment increased repression against immigrants, tightening of Germany's hitherto liberal asylum laws.

As a result of these conflicts, through the 1990s, small groups and circles associated with Anti-German ideas began to emerge throughout Germany, refining their ideological positions by dissenting from prevailing opinions within the German Left. These positions became particularly prominent within "Anti-fascist" groups. The Gulf War in 1990 consolidated the Anti-German position around a new issue, specifically criticism of the broader Left's failure to side with Israel against rocket attacks launched into civilian areas by the regime of Saddam Hussein.[6] Leading left-wing writers such as Eike Geisel and Wolfgang Pohrt criticised the German peace movement for failing to appreciate the threat posed by Ba'athism to left-wing movements through the Middle East, in particular around the Iraqi regime's use of poison gas.[6]

The outbreak of the Second Intifada provided another focal point for the emerging Anti-German movement. While other left-wing analysis identified Israel as an aggressor to the point they were perceived by the Anti-German movement as supporting Islamist groups such as Hamas, the Anti-German camp called for unconditional solidarity with Israel, explicitly Jews and other non-Arab groups native to the region against pan-Arabist ideology. This resulted in leading Anti-German publications including Konkret and Bahamas to draw links between the antisemitism of Islamist groups and the antisemitism of the Nazis, as both groups upheld the extermination of the Jews as central to their politics. This break with other left-wing positions was further intensified by the September 11 attacks on America, with Anti-Germans strongly criticising other leftist positions that claimed that Al-Qaeda's assault on the United States was motivated by anti-imperialist or anti-capitalist resistance against American hegemony,[6] instead claiming that Al-Qaeda and their attacks represented a modern form of fascism that needed to be stringently opposed.[7]

In 1995, the fiftieth anniversary of the bombing of Dresden, anti-Germans praised the bombing on the grounds that so many of the city's civilians had supported Nazism.[3] Kyle James points to this as an example of a shift towards support for the United States that became more pronounced after 9/11.[3] Similar demonstrations are annually held, the slogans "Bomber Harris, do it again!" and "Deutsche Täter sind keine Opfer!" ("German perpetrators are no victims!") have become common.[4]

The 1999 NATO bombing of Yugoslavia was also a focus of opposition for the anti-Germans, as for most of the radical left. Many anti-Germans condemned the war as a repetition of the political constellation of forces during the Second World War, with the Serbs in the role of victim of German imperialism. Some anti-Germans thus issued a call for "unconditional" support for the regime of Slobodan Milošević. The reasons the German government gave to legitimize the war – from an anti-German perspective – marked a turning point in the discourse of governmental history-policy.[12] The war was not justified "despite but because of Auschwitz". This judgment is often combined with the analysis of the genesis of a new national self as the "Aufarbeitungsweltmeister"[12] or "Weltmeister der Vergangenheitsbewältigung" (world champion in dealing with and mastering one's own past evil deeds).

Later Anti-German focal points included the Stop The Bomb Coalition, active in both Germany and Austria, to maintain sanctions against Iranian attempts to obtain nuclear weapons.

See also

Primary sources

- Harald Bergdorf and Rudolf van Hüllen. Linksextrem – Deutschlands unterschätzte Gefahr? Zwischen Brandanschlag und Bundestagsmandat. Schöningh, Paderborn and others (2011), ISBN 978-3-506-77242-8.

References

- Hirsch, Irmel (17 June 2006). "Antifaschistische Demo in Frankfurt" (in German). de.indymedia.org. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- Peters, Tim (2007). Der Antifaschismus der PDS aus antiextremistischer Sicht [The antifascism of the PDS from an anti-extremist perspective]. Springer. pp. 33–37, 152, 186. ISBN 9783531901268.

- "Strange Bedfellows: Radical Leftists for Bush". DW. Dw-world.de. 25 August 2006. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- "Verfassungsschutz des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen: 'Die Antideutschen – kein vorübergehendes Phänomen'" (in German). Retrieved 10 February 2007.

- "A Defense: Why we (the anti-Germans) are pro-Israel". Archived from the original on 2017-05-12.

- Moghadam, A.; Wyss, M. (Aug 2018). "Of Anti-Zionists and Antideutsche: The Post-War German Left and Its Relationship with Israel". Democracy and Security: 1–26. doi:10.1080/17419166.2018.1493991.

- Hagen, Patrick. "Die Antideutschen und die Debatte der Linken über Israel" (PDF) (in German). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2005. Retrieved 21 February 2007.

- "Letter from Berlin". Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- "Communism, anti-German criticism and Israel". Café critique. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- Harding, Luke (27 August 2006). "Meet the Anti-Germans". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- Aktualisiert, Zuletzt (26 May 2008). "15th anniversary of the arson attack in Solingen: All four perpetrators again today on the loose" (in German). RP Online. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- "Aufarbeitungsweltmeister" (PDF) (in German). Retrieved 18 November 2010.

Further reading

- "The Anti-Germans" - The Pro-Israel German Left, Simon Erlanger, Jewish Political Studies Review, 2009

- Who are the anti-germans?, Ça Ira, Freiburg May 2007

- The World Turned Upside Down, Mute magazine, 2005

- Statement by the anti-German group sinistra!, Copyriot

- 'Jubelperser' for Israel - an article about the Anti-German BAK Shalom within the German party The Left, Jerusalem Post, 2009

- "A Defence: Why We (the anti-Germans) Are Pro Israel"

- Die Antideutsche Ideologie, Robert Kurz, 2003