Alexandros Schinas

Alexandros Schinas (Greek: Αλέξανδρος Σχινάς, c. 1870 – May 6, 1913), also known as Aleko Schinas, assassinated King George I of Greece in 1913. Schinas has been variously portrayed as either an anarchist with political motivations (propaganda by deed), or a madman, but the historical record is inconclusive. The details of the assassination itself are known: on March 18, 1913, several months after Thessaloniki's liberation from the Ottoman Empire during the First Balkan War, King George I was out for a late afternoon walk in the city, and, as was his custom, lightly guarded. Encountering George on the street near the White Tower, Schinas shot the king once in the back from close range with a revolver, killing him. Schinas was arrested and tortured. He claimed to have acted alone, blaming his actions on delirium brought on by tuberculosis. After several weeks in custody, Schinas died by falling out of a police station window, either by murder or by suicide.

The details of Schinas's life before the assassination are unclear. He was a native Greek but his birthplace is disputed, likely either in the area of Volos or Serres. His occupation is also unconfirmed. Several years before the assassination, Schinas may have left Greece for New York City, returning in February 1913. Some contemporary sources reported that he advocated anarchism or socialism, and ran an anarchist school that was shut down by the Greek government. Other sources claim he was mentally ill, a foreign agent, or held a grudge against the king. Since his death, his true motivations have been the subject of much dispute.

Early life

Very little is confirmed about Schinas's life before he assassinated King George I.[1] Schinas was born around 1870, reportedly in the area of Volos or Serres, both of which were still under Ottoman control at the time.[2] He had two sisters, one older and one younger, and may have had a brother named Hercules who ran a chemist shop in Volos, where Schinas may have worked as an assistant. Schinas told an interviewer that he suffered from an unspecified "neurological condition" beginning at age 14.[3] Schinas may have studied or taught medicine in Athens, possibly at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. After leaving Athens, Schinas and his sisters taught in the Greek village Kleisoura before a dispute with his older sister forced him to resign. Schinas then moved to Xanthi and practiced medicine without authorization until stopped by authorities.[4]

Schinas's life after Xanthi is the subject of some dispute. Demetrios Botassi, the Greek consul general for New York in 1913, and other New York Greeks, told The New York Times that Schinas moved to Volos to open a school called the Centre for Workingmen with a doctor and a lawyer. The school was closed down by the government within months for "teaching anti-government ideas", and the doctor and lawyer were sentenced to three months in prison. For reasons unknown, Schinas was not punished. According to Botassi, during this period, Schinas also stood unsuccessfully as a candidate for the office of deputy from Volos in the Greek legislative body.[5]

Botassi's account was disputed by Bazil Batznoulis in a letter to Atlantis, a Greek paper in New York, which was republished by The New York Times shortly after the assassination. Batznoulis claimed that Schinas was born in Kanalia, not Volos. According to Batznoulis's letter, it was not Alexandros Schinas who ran for office in Volos, but another person named George Schinas. Batznoulis disputed that Alexandros Schinas was involved in the Centre for Workingmen school in Volos, writing: "Schinas had nothing to do with any school and had no idea of entering politics. He was known as a man who loved isolation and his backgammon. He wore a beard and was an anarchist."[6] Solon Vlasto, editor of Atlantis, endorsed Batznoulis's account and suggested that the many conflicting stories concerning Schinas's identity may be due to the fact that "Schinas" is a common surname in Greece and there were likely multiple people named "Aleko Schinas".[7]

Leaving Thessaloniki

In a post-assassination interview, Schinas stated that in 1910, he was deported from Thessaloniki (then still under Ottoman rule) for being "a good Greek patriot".[8] Botassi suggested another explanation for Schinas's departure to the US: that he was evading the police following the closure of the Centre for Workingmen school in Volos. Batznoulis, on the other hand, wrote that Schinas left because of a family quarrel with his brother Hercules.[9]

Schinas reportedly lived in New York City and worked at the Fifth Avenue and Plaza Hotels.[9] According to post-assassination newspaper reports, Schinas studied socialism[10] and frequented "radical circles" in New York's Lower East Side. At the Plaza Hotel, he reportedly distributed copies of English socialist Robert Blatchford's Merrie England to his co-workers.[11] Schinas was described as espousing "strange"[12] and "incomprehensible"[13] socialist views, and a general disdain for the monarchy.[14]

No known immigration or other records document Schinas's deportation from Thessaloniki or arrival in New York in 1910. However, immigration records document the arrival of a 36-year-old man named Athanasios Schinas (approximately the same age as Alexandros Schinas would have been at the time), a former resident of Kalavryta, Greece, arriving at Ellis Island aboard the ship La Gascogne from Le Havre, France on October 30, 1905. It is unclear whether Athanasios Schinas was the same person as Alexandros, or whether Alexandros travelled under an assumed name to avoid detection by Greek authorities.[9] In apparent contrast to reports of his emigration in 1910, a 1913 article in The New York Times reported that Schinas was still in Greece in 1911, stating that he applied that year for assistance at the king's palace but was refused and driven off by palace guards.[15]

Although it is uncertain when, why, or even whether he moved to New York City, Schinas was back in Greece by February 1913. According to post-assassination newspaper articles, about three weeks before the assassination, he traveled from Athens to Volos, then to Thessaloniki, possibly subsisting by begging[16] and eating eating only milk.[17] The Greek Minister of Justice reported that Schinas stayed at the house of a local lawyer until he was kicked out over a dispute involving blackmail.[13] In an interview while in custody, Schinas stated that some weeks prior the assassination, he had contracted tuberculosis, and a few days before the assassination, he was suffering from "severe high fevers" and "deliriums", and "was being taken over by madness".[18]

First Balkan War

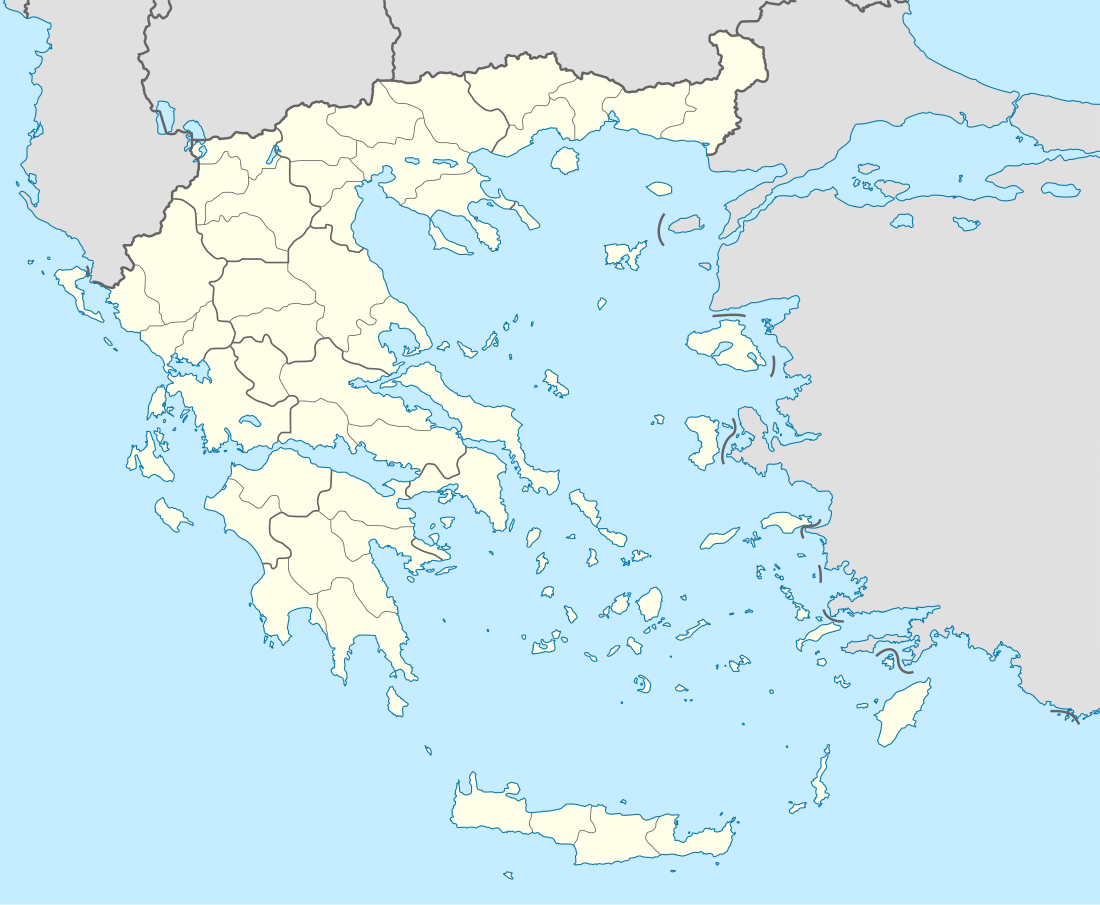

By the time Schinas arrived in Thessaloniki in February 1913, King George I had been staying there for several months, planning a celebration of the city's liberation from the Ottomans in the First Balkan War.[19] Greece had been ruled by the Ottoman Empire from the mid-fifteenth century until 1832 when it won independence with help from Britain, France, and Russia, who installed a Bavarian prince named Otto as the constitutional monarch of the new Kingdom of Greece.[20] Thirty years later, the "much-reviled"[21] Otto was overthrown, and Britain, France, and Russia, with approval of the Greek National Assembly, chose as his successor a 17-year-old Danish prince, who was crowned "George I, King of the Hellenes".[22]

Since independence, Greece had pursued the Megali Idea ("Great Idea"), an irredentist belief that one day Greek lands that remained under Ottoman control would be reclaimed and the Byzantine Empire would be restored.[23] Although Volos and other parts of Thessaly were ceded to Greece by the Ottomans in the 1881 Convention of Constantinople,[21] Greece had suffered a humiliating defeat in the First Greco-Turkish War in 1897 under the military leadership of George's eldest son, Prince Constantine,[24] and George survived an assassination attempt the following year.[25]

In 1908, Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II was deposed in the Young Turk Revolution,[26] inspiring a group of military officers to attempt the same in Greece.[27] What came to be known as the Goudi coup was defeated and George remained king, but new nationwide elections brought Eleftherios Venizelos to power as prime minister.[28][lower-alpha 1] Venizelos removed Constantine as Commander in Chief of Greece's armed forces and placed him in a largely ceremonial "Inspector General" role.[30] Constantine, who was married to German princess Sophia of Prussia, wanted Germany to train Greek troops, but Venizelos insisted on having the French train Greek troops instead.[31] On May 29, 1912, Greece signed a treaty with Bulgaria, becoming, with Serbia and Montenegro, the fourth member of the Balkan League, a coalition of nations that had recently broken away from the Ottoman Empire.[32] In October, Montenegro declared war on the Ottoman Empire and the rest of the League followed.[33]

George saw the First Balkan War as an opportunity to restore Greece's reptuation following its defeat fifteen years earlier.[34] The Balkan League's early gains soon led to divisions among the members over the spoils of war, primarily the geographically and economically important port of Thessaloniki, Greece's second-largest city.[35] In early November, Greek forces arrived in the city,[36] mere hours ahead of the Bulgarians.[37][lower-alpha 2] Constantine rode at the head of the Greek army through the city to the Konak Palace, where he received the Ottoman's sword of surrender.[39]

Greeks greeted the "liberation" of Thessaloniki with jubilation.[40] King George and Venizelos rushed to Thessaloniki to strengthen Greece's claims to the city.[41] George stayed in Thessaloniki to plan a victory celebration (coinciding with his golden jubilee) while the war continued elsewhere.[42] In February 1913, Ioannina, another Greek city long under Ottoman rule, was recaptured following the Battle of Bizani. George was popular with the people[43] and the Megali Idea was closer than ever before.[44]

Assassination of King George I

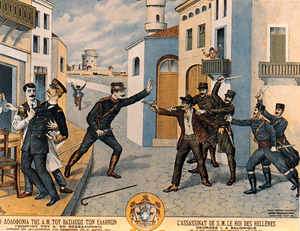

On March 18, 1913, George took his usual afternoon walk in Thessaloniki, accompanied by Greek Army officer Ioannis Frangoudis.[45] Against the urging of his advisers, the king refused to travel the city with a large number of guards; only two gendarmerie police officers were permitted to follow at a distance.[45] George and Frangoudis walked by the harbor near the White Tower of Thessaloniki,[lower-alpha 3] discussing the king's upcoming visit to the German battleship SMS Goeben. At approximately 5:15 p.m., on the corner of Vassilissis Olgas and Aghias Triadas streets,[47] Schinas shot George in the back at point-blank range with a revolver.[48] The bullet entered below the shoulder blade, pierced the heart and lungs, and exited the abdomen.[49] George collapsed and was taken by carriage to a nearby hospital. He died before arriving.[50][lower-alpha 4]

According to The New York Times, Schinas had "lurked in hiding" and "rushed out" to shoot George.[53] Another version described Schinas emerging from a Turkish cafe called the "Pasha Liman", drunk and "ragged", and shooting the king when he walked by.[54] Schinas did not attempt to escape afterwards and Frangoudis immediately apprehended him.[55] Additional gendarmerie arrived quickly from a nearby police station. Schinas reportedly asked the police to protect him from the surrounding crowd.[56] At the hospital, George's third son Prince Nicholas announced that George's eldest son Constantine I was now king.[57]

The assassination caused panic and anguish in Greece.[58] Contemporaneous reports described "spectators burst[ing] into tears"[53] at the king's funeral procession the following day.[12] Many suspected Schinas was an agent of the Bulgarians[59] or Ottomans.[60] Greek guards killed a few Muslim and Jewish residents of Thessaloniki they thought were responsible for the assassination.[61] Others believed Schinas worked for the Central Powers (Germany and Austria-Hungary),[62] seeking to replace George with Constantine, who was "very much a Prussian"[62] and suspected of being loyal to Germany over Greece.[63] Greece did not want to attribute a political motive to Schinas's actions.[64] To quell the public, the Greek government announced that the killer was Greek,[65] describing Schinas as a "feeble intellect,"[66] "criminal degenerate,"[67] and "victim of alcoholism."[68]

Motives

Schinas was tortured or "forced to undergo examinations" while in gendarmerie custody.[69] He did not name any accomplices.[70] According to Greek newspaper Kathimerini, Schinas told Queen Olga in a private meeting that he acted alone, and transcripts of depositions Schinas gave after his arrest were lost in a fire aboard a ship while being transported.[71]

In a March 1913 jailhouse interview with a newspaper reporter, Schinas was asked if his assassination of the king was premeditated, to which he replied:[8]

No! I assassinated the King by chance (it just happened). I was walking as a dead man (as a zombie) without knowing where I was going. Suddenly by turning my head I saw behind me the King with his adjutant. I slowed my pace. The King walked by me, very close to me. I let him walk by me and immediately, I fired.

No evidence has emerged supporting the various theories[72] that Schinas was an agent for the Ottomans, Bulgarians, Germans, or any other entity,[73] with scholars noting that the assassination destabilized the "delicate and hard-won peace" between the Greeks and Bulgarians,[74] and that George had already decided to abdicate in favor of Constantine at his upcoming golden jubilee, rendering German intervention unnecessary.[75]

The "state-issued narrative" of Schinas as a homeless alcoholic with anarchist beliefs has become the "accepted understanding".[76] Accordingly, his motivation for the assassination is commonly ascribed to his anarchist politics (as propaganda of the deed) or to mental illness (without political motivation).[77][78]

In the jailhouse interview, Schinas was asked "Are you an anarchist?", to which he replied:[8]

No, no! I am not an anarchist, but socialist. I become a socialist, when I was studying medicine in Athens. I do not know how. One becomes a socialist, without realising it, slowly (one step at a time). All people that are good and educated are socialist. The philosophy towards medicine, for me it was the socialism.

Some have asserted that the motive for the assassination was revenge for the king's refusal of request for assistance in 1911, or simply that Schinas had lost an inherited fortune in the Greek stock market, was in poor health, and despondent prior to the attack.[79][78] A scholar writing in 2014 described the gendarmerie's torture of Schinas as producing "a confused confession that mixed anarchist sentiments with a claim that 'he had killed the King because he refused to give him money.'"[36]

Another recent scholar has doubted that Schinas was an anarchist or that his actions were an example of propaganda by deed.[80] Writing in 2018, Michael Kemp noted that both "socialism" and "anarchism" were used interchangeably at the time, and that reports of Schinas as having run for political office or invested in a stock market do not support theories that Schinas was either a socialist or an anarchist.[81] Kemp wrote, "Rather than being part of a wider conspiracy, whether political or enacted by a state, Alexandros Schinas may have simply been a sick man (both mentally and physically) seeking an escape from the harsh realities of the early twentieth century."[82]

Schinas himself blamed "deliriums" brought on by tuberculosis, saying in the 1913 interview:[8]

During the night I was waking up, like I was being taken over by madness. I wanted to destroy the world. I wanted to kill everybody, because the whole of society was my enemy. Luck wanted that during this psychological condition to meet the King. I would have killed my own sister if I had met her that day.

Ultimately, the historical record is inconclusive.[83]

Death

On May 6, 1913, six weeks after being arrested, Schinas died by falling thirty feet (nine metres) out of a window from the office of the Examining Magistrate of the gendarmerie in Thessaloniki. He was approximately 43 years old.[84] The gendarmerie reported that Schinas, who was not handcuffed at the time, ran and jumped out of the window when the guards were distracted.[85] Some suggest Schinas may have committed suicide to avoid further gendarmerie "examinations" or a slow death from tuberculosis; others speculate that he was thrown from the window by the gendarmerie,[86] perhaps to keep him quiet.[62] After his death, his ear and hand were amputated and used for identification, then stored and exhibited at the Criminology Museum of Athens.[87]

More than a year after Schinas's death, The New York Times printed a retrospective article regarding recent political assassinations. The article did not list Schinas among "anarchists who believe in militant tactics", instead describing George I's "murderer" as "a Greek named Aleko Schinas who probably was half demented".[88]

Impact

Although they mourned the death of George, Greeks were enthusiastic about Constantine's ascent to the throne,[23] giving rise to a new Megali Idea rallying cry: "A Konstantine founded it [the Byzantine Empire]. A Konstantine lost it [with the fall of Constantinople in 1453]. And a Konstantine will get it back."[89] The Treaty of London formally ended the First Balkan War on May 30, but tensions between Greece and Bulgaria erupted in the Second Balkan War in June.[90] Greece was victorious again, nearly doubling its territory and population by the end of 1913.[91] Constantine did not, however, fulfill the Megali Idea.[89] When World War I erupted in 1914, division between Constantine and Venizelos over whether to support the Triple Entente (an alliance of Britain, France and Russia, the same nations that had helped Greece win its independence a century earlier) or the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria) led to the National Schism, which some historians suggest may have been avoided if not for Schinas's assassination of George I.[92]

Constantine removed Venizelos as prime minister, but ultimately the Triple Entente forced Constantine to abdicate in favor of his son Alexander, clearing the way for Venizelos to return as prime minister and for Greece to support the alliance.[93] In 1918, Greek troops "triumphantly marched" into the Ottoman capital Constantinople (now called Istanbul),[94] but the ensuing second Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922) was a "nightmare".[95] Venizelos was shot and wounded in 1920 by two monarchist naval officers, resulting in street violence between pro-monarchy and pro-Venizelos factions. Two months later, King Alexander was attacked and killed by monkeys while walking in the gardens at Tatoi Palace. Constantine returned to the throne and purged the "Venizelists". The Triple Entente revoked its financial support, putting Greece into significant debt.[96] Constantine advanced the Greek army into Turkey and was routed.[97] Another coup forced him to abdicate again. He died in exile while his younger brother Prince George took the throne as King George II.[98] The second Greco-Turkish war concluded with Greece returning territory to the Ottomans along borders that remained stable through to the 21st century, and an exchange of populations that moved 350,000 Muslims from Greece to Turkey and 1.3 million Greeks from Ottoman-controlled lands to Greece, ending "once and for all" the Megali Idea.[99]

Notes

- Venizelos was a Cretan politician who had successfully led a revolt on Crete that resulted in the resignation of George's second son Prince George as Crete's High Commissioner.[29]

- Bulgarian forces occupied a section of Thessaloniki.[38]

- After the city's liberation, the tower of Thessaloniki, an Ottoman prison dubbed the "Tower of Blood" and known for torture and executions, was whitewashed, changing it from a symbol of Ottoman oppression to a symbol of Greek unification and giving it its current name, the White Tower.[46]

- The last words of King George I of Greece are a matter of some dispute. The New York Times reported that the king's last words were, "Tomorrow, when I pay my formal visit to the dreadnought Goeben, it is the fact that a German battleship is to honor a Greek King here in Salonika that will fill me with happiness and contentment"[51]. However, George's biographer, Walter Christmas, wrote in the king's biography that "the last words that left the King's lips" were: "Thank God, Christmas can now finish his work with a chapter to the glory of Greece, of the Crown Prince and of the Army."[52]

References

- Kemp 2018, p. 179: "Little is known of Schinas' life before the assassination."; Jensen 2016, p. 38: "... information on him is patchy."

- Kemp 2018, p. 179; Tomai 2012.

- Kemp 2018, pp. 178–179.

- Kemp 2018, pp. 179–180.

- Kemp 2018, p. 180; Jensen 2016, p. 38: "He started an anarchist school in his hometown--which the Greek government closed down ..."; The New York Times 1913c.

- Kemp 2018, p. 180; The New York Times 1913f.

- The New York Times 1913f.

- Magrini 1913, p. 185.

- Kemp 2018, pp. 180–181.

- Kemp 2018, p. 181; Jensen 2016, p. 38: "If newspaper accounts are correct, he had read everything on 'the subject of socialism' and had been a fervent anarchist for years."

- Kemp 2018, p. 181.

- Tomai 2012.

- Anastasiadēs 2010, p. 60.

- Kemp 2018, p. 184; Jensen 2016, p. 38: "... and frequently expressed his dislike for the Greek monarchy ... a generalized hatred for the Greek monarchy."; The New York Times 1913c.

- Kemp 2018, pp. 181–182; The New York Times 1913e.

- Kemp 2018, p. 182; Tomai 2012.

- Tomai 2012; The New York Times 1913e.

- Kemp 2018, p. 182; The New York Times 1913e.

- Kemp 2018, p. 178; Newton 2014.

- Kemp 2018, pp. 178-179.

- Kemp 2018, p. 179.

- Gallant 2001, p. 45.

- Kaloudis 2019, p. 63; Shirinian 2017, p. 307.

- Newton 2014, p. 179; Anastasiadēs 2010, p. 56.

- Newton 2014, p. 180; Anastasiadēs 2010, p. 56.

- Kaloudis 2019, pp. 57-61; Shirinian 2017, p. 303.

- Kaloudis 2019, p. 39; Newton 2014, p. 180; Gallant 2001, p. 121.

- Kaloudis 2019, pp. 39-61; Gallant 2001, pp. 118-123.

- Gallant 2001, pp. 116-118.

- Kaloudis 2019, p. 61; Gallant 2001, p. 125.

- Kaloudis 2019, p. 61.

- Kaloudis 2019, p. 60; Shirinian 2017, p. 303.

- Kaloudis 2019, pp. 61-62; Newton 2014, p. 179.

- Newton 2014, p. 179: "When Montenegro declared war on Turkey in October 1912, igniting the First Balkan War, King George I of Greece was determined to salvage his country's reputation, soiled by humiliation in the Greco-Turkish War of 1897."

- Kemp 2018, p. 179; Newton 2014, p. 179; Gallant 2001, p. 128.

- Newton 2014, p. 179.

- Kaloudis 2019, p. 62; Kemp 2018, p. 179; Gallant 2001, p. 128.

- Kaloudis 2019, p. 62.

- Gallant 2001, p. 128.

- Gallant 2001, p. 128: "All across Greece the news of Thessaloniki's 'liberation' was greeted with outbursts of jubilation. Special masses were celebrated to commemorate the event."

- Kaloudis 2019, p. 62; Gallant 2001, p. 128: "In a ploy to strengthen Greek claims to the city, King George and Venizelos hastened to join the army."

- Kemp 2018, p. 178; Newton 2014, p. 179.

- The National Herald 2017; Gallant 2001, p. 128-129.

- Kaloudis 2019, pp. 61-62; Gallant 2001, pp. 127-128.

- Kemp 2018, p. 178; Mattox 2015; Christmas 1914, p. 406.

- Kemp 2018, p. 178; Glenny 2001, p. 181.

- Kathimerini 2006: "On March 5, 1913, at the intersection of Vassilissis Olgas and Aghias Triadas streets, Alexandros Schinas, a misfit from Asvestohori, shot and killed King George I. The motive has never been revealed nor has Schinas's testimony in depositions to authorities - a fire broke out on the steamship carrying them to Piraeus. It is reported that in a private conversation with the king's widow, Queen Olga, he stated that he had acted alone, but most historians take the view that he acted on behalf of foreign interests in the Balkans that benefited from the king's murder."

- Kemp 2018, p. 178; West 2017, p. 83.

- Christmas 1914, p. 407; The New York Times 1913f.

- Kemp 2018, p. 178; Mattox 2015; Newton 2014; Christmas 1914, p. 407–408.

- The New York Times 1913.

- Christmas 1914, p. 407.

- The New York Times 1913e.

- Ashdown 2011, p. 185; Christmas 1914, p. 406–407.

- West 2017, p. 83.

- Kemp 2018, p. 183; Christmas 1914, p. 407.

- Newton 2014; Christmas 1914, p. 410, 412–416; The New York Times 1913b.

- Kaloudis 2019, p. 62; Tomai 2012; Kathimerini 2006.

- Kaloudis 2019, p. 63; Kemp 2018, p. 179; Shirinian 2017, p. 304; Newton 2014, p. 179; Tomai 2012; Gallant 2001, p. 129: "The murderer, Alexandras Schinas, said he killed the King because he would not give him some money, but most Greeks believed that the killer was a Bulgarian agent."

- Kemp 2018, p. 179; Shirinian 2017, p. 304; Kathimerini 2006.

- Anastasiadēs 2010, pp. 58-60.

- Kaloudis 2019, p. 63.

- Shirinian 2017, p. 304; Newton 2014, p. 179; Tomai 2012; Anastasiadēs 2010, p. 55; Kathimerini 2006.

- Kemp 2018, p. 178: "The assassin of King George I was Alexandros Schinas, and the nascent Greek state was keen not to ascribe a political motive to his actions."

- Anastasiadēs 2010, pp. 58.

- The New York Times 1913b.

- The Times 1913b.

- Kemp 2018, p. 179; The Times 1913c.

-

- Kemp 2018, p. 183: "During his detention Schinas was 'forced to undergo examinations, which failed to elicit any facts to show that other persons were implicated.' One can only imagine what such examinations entailed, but given the popularity of his victim and the oppressive nature of the Greek gendarmerie, it is highly probable that coercion, physical torture and beatings were liberally applied to Schinas by largely conservative and militarized gendarmes of the day. Little is known of Schinas' time in custody other than the suspected abuse that he likely suffered as part of his interrogations."

- Newton 2014, p. 179: "In custody, Schinas initially refused to speak, but was 'forced to undergo examinations'–understood to mean torture–finally producing a confused confession that mixed anarchist sentiments with a claim that 'he had killed the King because he refused to give him money.'"

- The New York Times 1913e

- Kemp 2018, p. 183; Jensen 2016, p. 38: "Moreover, all the assassins insisted that they had indeed acted without accomplices, and this is certainly true of Lucheni, Czolgosz, and Schinas."

- Kathimerini 2006.

- Kemp 2018, p. 182 (Bulgaria or Ottoman Empire); The National Herald 2017 (Bulgaria, Germany, or Ottoman Empire); Newton 2014, p. 179 (Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, or Germany); Tomai 2012 (Austria-Hungary); Ashdown 2011, p. 185 (Macedonia); Kathimerini 2006 (Bulgaria, Germany, or Ottoman Empire); Gallant 2001, p. 129 (Bulgaria); Christmas 1914, pp. 411–412 (Bulgaria or Ottoman Empire); UPI 1913 (Ottoman Empire)

-

- Kemp 2018, p. 182: "Another theory is that Schinas, rather than acting of his own volition, was actually acting on behalf of the Turks or the Bulgarians...This conspiracy theory explaining Schinas' actions has several parallels to those pertaining to the assassination of John F. Kennedy (a populist leader with a reduced security detail, supposedly assassinated by mysterious forces acting through a dupe), but its accuracy is questionable. Although many details of Schinas' life are presently unknown (and at the time of the regicide the atmosphere in Thessaloniki was doubtless tense), no evidence that Schinas was acting as an agent for the Ottoman Empire, the Bulgarians, or any other entity has emerged."

- Newton 2014, p. 179: "Conspiracy theories linking Schinas to plotters from Bulgaria, Germany, or Austria-Hungary were never substantiated."

- Ashdown 2011, p. 185: "No evidence was ever found to confirm that story; nor did any nationalist group claim King George's death as their achievement."

- Christmas 1914, p. 412: "I scarcely think there is any necessity to go into the hateful suggestion that one of the Allies of Greece should have sought to promote its ambitions by getting rid of the King. The result of the examination points to the assassin alone. By the myth that immediately came into existence still lives, and it undoubtedly contributed to strengthen the ill-will that was felt for the Bulgarians long before the murder. And the growth of the myth was encouraged by the circumstance that Alexander Skinas avoided further investigations by suicide."

- UPI 1913: "No confirmation of this was forthcoming, though, and nothing developed in Saloniki to indicate the Turks had anything to do with the killing of the Greek king."

- Kemp 2018, p. 179: "Although there is strong historical evidence to support conflict between the Greek and Bulgarian states at the time of King George I's death, such conflict was for the most part political in nature. Indeed, the assassination of the king served to destabilize a delicate and hard-won peace."

- Anastasiadēs 2010, p. 55; Gallant 2001, p. 129: "Ironically, just before he was slain, George had decided that he would take the opportunity of the forthcoming jubilee celebration of his coronation to abdicate in favour of Konstantine."

-

- Kemp 2018, p. 178: "He is understood and defined as a lone Anarchist actor, and his regicide is assumed to be an example of propaganda of the deed. He is described as being of "feeble intellect," a "criminal degenerate," and a "victim of alcoholism." Over time, the state-issued narrative has become the accepted understanding of Schinas."

- Kemp 2018, p. 181: "The accepted position is that he was a homeless alcoholic with Anarchist tendencies."

- West 2017, p. 83: "King George of Greece was shot in the back during an afternoon stroll through the streets near Thessaloniki's White Tower on 18 March 1913 by an anarchist, Alexandros Schinas."

- Jensen 2016, p. 38: "Perhaps Alexandros Schinas, who became the assassin of King George I of Greece in 1913, should also fall into the category of a convinced anarchist who acted because of ideologically formed views, although information on him is patchy. If newspaper accounts are correct, he had read everything on "the subject of socialism" and had been a fervent anarchist for years. He started an anarchist school in his hometown--which the Greek government closed down--and frequently expressed his dislike for the Greek monarchy."

- Jensen 2015, p. 121: "While the assassin of King George I of Greece in March 1913 has often been written off as simply a madman, evidence from people who knew Aleko Schinas when he lived in the United State attests to his intelligence and firm anarchist convictions."

- Mattox 2015, p. 22: "His assailant, a Greek named Aleko Schinas, a confirmed Anarchist said to be well eduated, had worked at one time in New York. His principal grievance evidently was the closure by the government of a school of Anarchism he had established in Greece."

- Newton 2014, p. 179: "In custody, Schinas initially refused to speak, but was 'forced to undergo examinations'–understood to mean torture–finally producing a confused confession that mixed anarchist sentiments with a claim that 'he had killed the King because he refused to give him money.'"

- Jensen 2013, p. 21: "In March 1913, an 'educated anarchist' shot to death King George I of Greece."

- New International Encyclopedia 1914, p. 590: "On March 18, 1913, King George of Greece was assassinated at Salonika by an anarchist named Aleko Schinas."

- UPI 1913: "Searching inquiry was set afoot today by the Greek government to determine if possible whether Aleke Schinas was simply an unbalanced anarchist, acting alone, when he shot down King George in a Saloniki street yesterday or whether he was the crafty agent of an organized anarchist band. A rendezvous of anarchists exists at Voto and the ministry heard a report that the plot to kill King George was hatched there. It was rumored here the assassination of the king was but the beginning of an anarchist project to murder the rulers of all the Balkan states, Czar Ferdinand of Bulgaria, King Nicholas of Montenegro, and King Peter of Servia also were said to be marked."

- Kemp 2018, p. 183: "The assassination of King George I is commonly thought to be an example of Anarchist propaganda of the deed (indeed, Schinas is typically referenced as a follower of this philosophy) or the work of a lone madman, motivated by non-political factors. Schinas has been characterized both as an educated and criminally motivated Anarchist and as a hopeless and mentally unbalanced alcoholic."

-

- Kemp 2018, p. 184: "Rather than being part of a wider conspiracy, whether political or enacted by a state, Alexandros Schinas may have simply been a sick man (both mentally and physically) seeking an escape from the harsh realities of the early twentieth century."

- Jensen 2016, pp. 38-39: "Other reports have tried to write him off as simply a neurasthenic ... None of the nine famous anarchist assassins of monarchs and heads of state and government--with the possible exception of Schinas--were mentally deranged."

- Clogg 2002, p. 241: "In March 1913, while on a visit to Salonica, which had been newly incorporated into the Greek state, he was assassinated by a madman."

- Gallant 2001, p. 129: "In March 1913, King George fell prey to an assassin's bullet. A Greek madman espied the aged monarch out on his daily afternoon walk along the waterfront in Thessaloniki, approached him, and shot him in the back."

- Kemp 2018, pp. 184-185; Jensen 2016, p. 38: "Perhaps Schinas acted more to revenge a personal, rather than a political, slight--the king had refused his petition for assistance--although this was in the context of a generalized hatred for the Greek monarchy."

-

- Kemp 2018, p. 180: "[Botassi] described Schinas as a 'man of education and a confirmed anarchist.' This allegation seems somewhat opposed to Schinas' own later protestations and those of others who shared his Socialist beliefs."

- Kemp 2018, p. 183: "Regardless of the motivating factors that lay behind the regicide (which were almost certainly not, as commonly presumed, part of a wider campaign of propaganda of the deed), the consequences to Schinas were severe."

- Kemp 2018, p. 184: "What is clear is that the understanding that Schinas acted as a motivated Anarchist attacker is inherently flawed."

-

- Kemp 2018, p. 180: "It is worth considering, however, that during the nineteenth century the terms 'Socialism' and 'Anarchism' were often used interchangeably. Although there is significant gulf between ideas of remodeling the state and those that aim to remove it altogether, many public figures and press reports of the time ignored this distinction; indeed, both Socialism and Anarchism were seen as a grave social and political threats in the public and media consciousness."

- Kemp 2018, p. 180: "Also according to Botassi, it was during this period that Schinas unsuccessfully stood as a candidate for the office of deputy from Volos for the Greek legislative body. This abortive attempt to join the ranks of the political class did not meet with success, but again, it hardly seems consistent with the actions of a supposed Anarchist radical."

- Kemp 2018, p. 181: "Although an inheritance may well have provided a reason for Schinas to return to Greece following his deportation, it seems unlikely that either a committed Socialist or an avowed Anarchist would invest funds in the unreservedly capitalist stock exchange."

- Kemp 2018, p. 184.

- Kemp 2018, p. 184: "Schinas remains an elusive figure and a controversial one. The results of his actions are readily apparent, but what prompted them and, indeed, the details of the man behind them remain ephemeral, drawn as they are from muddled statements provided by multiple sources."

- Magrini 1913, p. 185: "I am now forty-three!"

- The New York Times 1913g.

- Kemp 2018, p. 183; West 2017, p. 83; Newton 2014.

- Kemp 2018, p. 183.

- The New York Times 1914.

- Gallant 2001, p. 129.

- Kaloudis 2019, p. 63; Kemp 2018, p. 179; Shirinian 2017, p. 304; Gallant 2001, p. 128.

- Kaloudis 2019, p. 64; Gallant 2001, p. 128.

- Kaloudis 2019, p. 64; Tomai 2012; Anastasiadēs 2010, p. 56; Gallant 2001, pp. 129-130; Dakin 1972, p. 203.

- Gallant 2001, p. 129-134.

- Gallant 2001, p. 134.

- Gallant 2001, p. 139.

- Gallant 2001, p. 139-140.

- Gallant 2001, p. 141-144.

- Gallant 2001, p. 143-144.

- Gallant 2001, p. 145-146.

Sources

- Anastasiadēs, Giōrgos O. (Αναστασιάδης, Γιώργος Ο.) (2010). "Part B Chapter 2 Η δολοφονία του βασιλιά Γεώργιου Α' (1913)"". To palimpsēsto tou haimatos : politikes dolophonies kai ekteleseis stē Thessalonikē (1913-1968) (1. ekd ed.). Thessalonikē: Epikentro. ISBN 978-960-458-280-8. OCLC 713835670.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ashdown, Dulcie M. (2011-08-26). Royal Murders: Hatred, Revenge and the Seizing of Power. The History Press. ISBN 9780752469195. Archived from the original on 2018-12-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Christmas, Walter (1914), King George of Greece, translated by Chater, Arthur G., NY: McBride, Nast & Co, ISBN 9781517258788CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clogg, Richard (2002). A Concise History of Greece. Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dakin, Douglas (1972). The Unification of Greece, 1770-1923. Ernest Benn Limited. ISBN 9780510263119. OCLC 2656514.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gallant, Thomas W. (2001). Modern Greece. London: Arnold. ISBN 9780340763360.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Glenny, Misha (2001). "A maze of conspiracy". The Balkans: Nationalism, War and the Great Powers, 1804-1999 (Penguin 2001 softcover ed.). New York City: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140233773. OCLC 868525206.

- Jensen, Richard Bach

- Jensen, Richard Bach (2013). "The first global wave of terrorism and international counter-terrorism". In Hanhimäki, Jussi M.; Blumenau, Bernhard (eds.). An International History of Terrorism: Western and Non-Western Experiences. Routledge. p. 21. ISBN 9780415635400. Archived from the original on 2018-12-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jensen, Richard Bach (2015-03-27). "Anarchist terrorism and counter-terrorism in Europe and the world, 1878–1934". In Law, Randall D. (ed.). The Routledge History of Terrorism. Routledge. p. 121. ISBN 9781317514879. Archived from the original on 2018-12-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jensen, Richard Bach (2016-02-05). "Historical lessons: an overview of early anarchism and lone actor terrorism". In Fredholm, Michael (ed.). Understanding Lone Actor Terrorism: Past Experience, Future Outlook, and Response Strategies. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-32861-2. OCLC 947086466.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kaloudis, George (2019-10-04). Navigating Turbulent Waters: Greek Politics in the Era of Eleftherios Venizelos. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4985-8739-6. OCLC 1108993066.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Four famous targets of assassination in Salonica". Kathimerini. 2006-12-18. Archived from the original on 2018-12-10. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

- Kemp, Michael (2018). "Beneath a White Tower". Bombs, Bullets and Bread: The Politics of Anarchist Terrorism Worldwide, 1866–1926. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. pp. 178–186. ISBN 978-1-4766-7101-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Magrini (March 1913), translated by Fragkos, Grigorios, "The King's Assassin Explains Himself to the Journalist Magrini", Aionos, retrieved 2018-12-08CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) as published in Kemp 2018, pp. 184–186

- Mattox, Henry E. (2015-06-08). Chronology of World Terrorism, 1901–2001. McFarland. ISBN 9781476609652. Archived from the original on 2019-05-07.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "The Assassination of King George – March, 1913". The National Herald. 2017-06-21. Archived from the original on 2018-12-10. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

- The New York Times

- a. "King of Greece murdered at Salonika; slayer mad; political results feared" (PDF). The New York Times. Marconi Transaltantic Wireless Telegraph. 1913-03-19. Retrieved 2018-12-02.

- b. "Died before reaching hospital" (PDF). The New York Times. 2013-03-19. Retrieved 2018-12-02.

- c. "The assassin lived here" (PDF). The New York Times. 2013-03-20. Retrieved 2018-12-02.

- d. "King's Murderer is Educated Anarchist" (PDF). The New York Times. Marconi Transatlantic Wireless Telegraph. 1913-03-20. Retrieved 2018-12-02.

- e. "King's murderer is educated anarchist (part 2, Salonika)" (PDF). The New York Times. 1913-03-20. Retrieved 2018-12-02.

- f. "Salonika (untitled)" (PDF). The New York Times. 1913-03-21. Retrieved 2018-12-02.

- g. "King's slayer a suicide" (PDF). The New York Times. 1913-05-07. Retrieved 2018-12-02.

- h. "Many rulers fell at fanatics' hands" (PDF). The New York Times. 1914-06-29. Retrieved 2018-12-02.

- The Times (London)

- a. "King of Hellenes murdered". The Times (London). 1913-03-19. p. 6.

- b. "The murdered king". The Times (London). 1913-03-19.

- b. "Murder at Salonica". The Times (London). 1913-03-20.

- Newton, Michael (2014-04-17). Famous Assassinations in World History: An Encyclopedia [2 volumes]. Santa Barbara, CA, USA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781610692861. Archived from the original on 2018-12-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Propaganda of the Deed". New International Encyclopedia. Dodd, Mead. 1914. Archived from the original on 2018-12-10.

- Shirinian, George N. (2017-02-01). Genocide in the Ottoman Empire: Armenians, Assyrians, and Greeks, 1913-1923. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-78533-433-7. OCLC 1100925364.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tomai, Fotini (2012-10-21). "Ο Γεώργιος Α' και ο δολοφόνος του - νέα - Το Βήμα Online". Βήμα Online (in Greek). Archived from the original on 2018-12-10. Retrieved 2018-12-01.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- West, Nigel (2017). Encyclopedia of political assassinations. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-5381-0238-1. OCLC 980219049.

- "Anarchists plot to murder all Balkan kings, Greece hears". United Press International. 1913-03-19. Archived from the original on 2018-12-10. Retrieved 2018-12-09.