Pacific Crest Trail

The Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) travels 2,650 mi (4,260 km) along the west coast of the United States, from Mexico to Canada. It passes through California, Oregon, and Washington State. The PCT is one of the original National Scenic Trails established by Congress in the 1968 National Trails System Act. It is administered by the US Forest Service. The Forest Service partners with the Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service, California State Parks, and the Pacific Crest Trail Association to provide effective management and protection of the trail.

- This article is an itinerary.

Understand

The 2,663 mi (4,286 km) long Pacific Crest Trail ranges in elevation from just above sea level at the Oregon-Washington border to 13,153 feet (4,009 m) at Forester Pass in the Sierra Nevada. The route passes through 25 national forests and 7 national parks. Its midpoint is in Chester, California (near Mt. Lassen), where the Sierra and Cascade mountain ranges meet.

History

The Pacific Crest Trail was proposed by Clinton C. Clarke as a trail running from Mexico to Canada along the crest of the mountains in California, Oregon, and Washington. The original proposal was to link the John Muir Trail, the Tahoe-Yosemite Trail (both in California), the Skyline Trail (in Oregon) and the Cascade Crest Trail (in Washington).

The Pacific Crest Trail System Conference was formed by Clarke to both plan the trail and to lobby the federal government to protect the trail. The conference was founded by Clarke, the Boy Scouts, the YMCA, and Ansel Adams (amongst others). From 1935 through 1938, YMCA groups explored the 2000 miles of potential trail and planned a route, which has been closely followed by the modern PCT route.

In 1968, President Lyndon Johnson defined the PCT and the Appalachian Trail with the National Trails System Act. The PCT was then constructed through cooperation between the federal government and volunteers organized by the Pacific Crest Trail Association. In 1993, the PCT was officially declared finished.

Thru hiking

Thru hiking is a term used in referring to hikers who complete long distance trails from end-to-end in a single trip. The Pacific Crest Trail, Appalachian Trail, and Continental Divide Trail were the first three long-distance trails in the U.S. Through-hiking all of these three trails is known as the Triple Crown of Hiking. Thru-hiking is a long commitment, usually taking between four and six months, that requires thorough preparation and dedication. Although the actual number is difficult to calculate, it is estimated that around 180 out of approximately 300 people who attempt a thru-hike complete the entire trail each year.

Prepare

The most common cause of failure to complete the PCT is lack of preparedness. It is important to begin regular walks in the months and weeks leading up to the thru-hike, beginning with low-impact day-hikes in easy terrain while carrying a minimum of weight. When these day-hikes become nearly effortless, increase the distance and include several multi-day hikes that require a full backpack with food, water and gear. In addition, hilly terrain should be incorporated as soon as possible in order to build up strength in the muscles required for climbs and descents. Performing regular hikes that continually push the body's current limits will not only toughen the body but will also go a long way toward mentally preparing oneself for the constant strain on body and mind.

Preparing financially and logistically are also essential to a successful thru-hike. The cost of a hike will range from several hundred dollars a month on the low end to upwards of a thousand dollars a month for the high end. Each person has a different minimum level of comfort and nourishment; it is vital to discover what one's own level is as early as possible and to make supply arrangements accordingly. Study the route and identify towns that will serve as likely resupply centers and map out distances between post offices. An experienced thru-hiker resupplies his or her dry goods every 10-14 days, either through the post offices' general delivery drop-box system or through local purchases. The average thru-hiker plans for six to eight months before the actual hike. In a few cases, the PCT passes through or near towns and resorts where supplies can be purchased. In other cases the trail users may need to get off the trail and travel to a town. Contact the PCTA website for additional information on resupplying along the trail.

Much of this info is available in the Wilderness backpacking travel section, but generally equipment should be purchased well in advance of the PCT start date and should be used as many times as possible to both allow the hiker to become familiar with the gear (backpacks adjusted properly, boots broken in, etc.) and to identify any broken, impractical or unsatisfactory items. Prospective thru-hikers should get in contact with local hiking clubs and solicit advice on what pieces of equipment are completely unnecessary, which are luxury items and which are essential. Different hikers have different philosophies on how much gear should be taken, from those in the "lean and fast" school of thought which advocates a minimum of everything - no stove, no tent, hiking sandals instead of boots and little else - to the "slow and comfortable" school which sacrifices speed and low weight for comfort. One should get as many opinions as possible and attempt hikes with various levels of gear until an acceptable amount of weight and speed has been achieved.

Fire permits are needed in many areas, and fire closures may exist during extremely dry times of year. Above certain elevations or in some areas fires are not permitted. Please check ahead of your trip to determine if a fire permit is needed and where it can be obtained.

Many of the wilderness areas, National Parks and other special management areas require an overnight use permit. Please check with the local area to determine if a permit is needed and where it can be obtained. People undertaking a trip of 500 miles or longer should contact the Pacific Crest Trail Association for a permit.

Water is essential when traveling on the PCT. Depending on what location you are in, time of year and if there are water sources along your travel route will help determine how much water to carry. Filter and purify all water obtained from any natural source along the PCT.

Buy

Useful information about the trail is provided by the Pacific Crest Trail Association. To understand the trail it has been divided in many guidebooks into 3 sectors.

- Southern California (Mexico-Tuolumne Meadows, Yosemite)

- Northern California (Tuolumne Meadows, Yosemite-Oregon)

- Pacific Northwest (Oregon-Canada)

The US Forest Service has broken the trail down into 10 different maps, which are available online through the National Forest Store .

Map #1 Southern California, Map #2 Transverse Ranges, Map #3 Southern Sierra, Map #4 Central Sierra, Map #5 Northern Sierra, Map #6 Not Yet Available, Map #7 Southern Oregon, Map #8 Northern Oregon, Map #9 Southern Washington, Map #10 Northern Washington

The Pacific Crest Trail Association cites Ray Jardine’s book, Beyond Backpacking, as a great resource for hikers during the planning process. Beyond Backpacking is a “how-to” book for ultralight hikers. In this book Jardine explains how to trim every extra ounce from one’s pack weight by doing everything from cutting extra straps off your pack to eating only food that does not have to be cooked

Get in

There are many sections of the trail that can be hiked individually, but the PCT departs from the Mexican border near the small town of Campo, and ends at Monument 78 on the Canadian border. The first thing prospective thru hikers have to do before attempting a thru hike is to plan out and sketch out their trip. In general the decision of which route to take needs to be considered. While most hikers travel from the Southern Terminus at the Mexico Border northward to Manning Park, British Columbia, some hikers prefer a southbound route. In a normal weather year, northbound hikes are most practical due to snow and temperature considerations. If snowpack in the Sierra Nevada is high in early June and low in the Northern Cascades, some hikers may choose to 'flip-flop.' Flip-flopping can take many forms but often describes a process whereby a hiker begins at one end (on the PCT, usually the southern end) of the trail and then, at some point, like reaching the Sierra, 'flips' to the end of the trail (Manning Park in B.C.) and hikes southbound to complete the trail. However, it is not possible to legally enter the United States from Canada by using the Pacific Crest Trail.

Hike

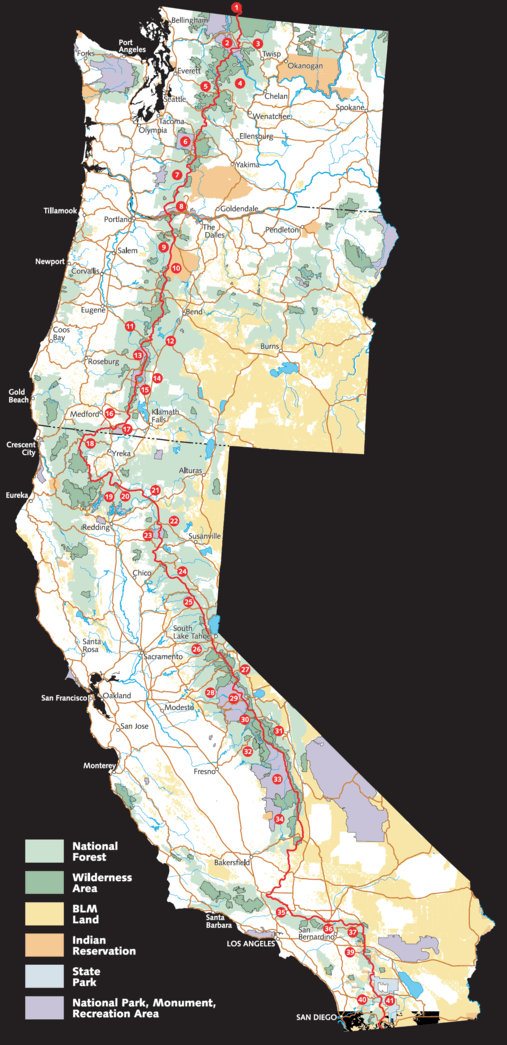

The following notable locations are found along or adjacent to the route of the Pacific Crest Trail. They are listed from south to north to correspond with the itinerary typically followed by thru-hikers to take advantage of the best seasonal weather conditions. The numbers in parentheses correspond to the numbers on the PCT overview map.

California

- Campo, California, near the trail's southern terminus at the Mexico – United States border

- Anza-Borrego Desert State Park (41)

- Cleveland National Forest (40)

- Big Bear Lake

- Cajon Pass

- Angeles National Forest (35)

- Vasquez Rocks

- Agua Dulce

- Walker Pass

- Owens Peak Wilderness (34)

- South Sierra Wilderness (34)

- Golden Trout Wilderness (34)

- Kings Canyon National Park (33)

- Forester Pass, highest point on the trail

- John Muir Wilderness (31)

- Ansel Adams Wilderness (30)

- Yosemite National Park (29)

- Tuolumne Meadows

- Sonora Pass, Ebbetts Pass, Carson Pass

Yosemite National Park, California

Yosemite National Park, California - Desolation Wilderness

- Lassen National Forest (22)

- McArthur-Burney Falls Memorial State Park (21)

- Shasta-Trinity National Forest (19)

- Castle Crags Wilderness (20)

- Klamath Mountains

- Trinity Alps Wilderness

- Russian Wilderness

- Marble Mountain Wilderness

Oregon

- Cascade–Siskiyou National Monument (17)

- Rogue River National Forest (16) and Winema National Forest (14)

- Sky Lakes Wilderness

- Crater Lake National Park (15)

- Umpqua National Forest (13)

- Mount Thielsen

- Willamette National Forest (11) and Deschutes National Forest (12)

- Diamond Peak Wilderness

- Waldo Lake

- Three Sisters Wilderness

- McKenzie River

- Mount Washington Wilderness

- Mount Jefferson Wilderness

- Mount Hood National Forest (9)

- Olallie Scenic Area

- Warm Springs Indian Reservation (10)

- Timberline Lodge

- Mount Hood Wilderness

- Lolo Pass

- Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area (8)

- Mark O. Hatfield Wilderness (formerly the Columbia Wilderness)

- Cascade Locks Oregon, lowest point on the trail

- Bridge of the Gods (links Oregon and Washington, crossing the Columbia River)

Washington

- Gifford Pinchot National Forest (7)

- Indian Heaven Wilderness

- Mount Adams

- Goat Rocks Wilderness

- White Pass

- Mount Rainier National Park (6)

- Chinook Pass

- Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest (5)

- Norse Peak Wilderness

- Alpine Lakes Wilderness

- Henry M. Jackson Wilderness

- Glacier Peak Wilderness

- Snoqualmie Pass

- Stevens Pass

- Lake Chelan National Recreation Area

- Stehekin Washington, last town along the trail, 10 mi from PCT by National Park Service bus

- North Cascades National Park (2)

- Okanogan National Forest (3)

- Pacific Northwest National Scenic Trail

- Boundary Monument 78, at the Canada – United States border

British Columbia, Canada

- E.C. Manning Provincial Park, the northern terminus of the trail (1)

Stay safe

The trail traverses through some of the most extreme wilderness in the continental USA. Trail users should be prepared for any emergency and accordingly plan ahead. It is best to be familiar with outdoor travel by reading about the area you may be traveling in and learn about potential hazards. Basic understanding of how to prevent hypothermia and heat exhaustion or how to avoid and treat poisonous plants and animals among other potentially life threatening situations can help to ensure that your time on the PCT will be rewarding. Always letting others know where you are going and when you plan to return is a basic premise when traveling in remote areas.

There's no reason to fear the mountains, as long as you approach them with proper respect and preparation. As with anywhere else, recklessness and a lack of forethought can get you into trouble, especially in areas with vast and remote back country.

- Altitude sickness - Can lead to dizziness, headaches, nausea, even blackouts and pulmonary edema. Give your body a few days to adjust to the high altitudes before going full throttle with your hiking.

- Dehydration - When you engage in strenuous outdoor activities, be sure to replenish your fluids as you go. You may be losing moisture through your mouth and nose and through sweating, but be completely unaware due to the arid mountain air. May result in dizziness, intense thirst and elevated heart and breath rates.

- Giardia - Drinking untreated water from regional streams is not a good idea owing to Giardia parasites, but tap water is not a problem.

- Hypothermia - Prolonged exposure to the cold can result in confusion, a slowed heart rate, lethargy, even death. Dress warmly in non cotton clothing to allow any sweat to wick away from your body and evaporate. Otherwise, it may thoroughly chill you later in the day when temperatures drop.

- Frostbite - During periods of severe cold, your circulatory system pulls all your warming blood into the core of your body to protect your vital organs. This makes your extremities such as your ears, fingers and nose especially vulnerable. Wear a face mask, insulated gloves and other heavy gear on the worst winter days.

- Sunburn - Lather up with sunscreen, even if there's cloud cover. The high mountain elevations means you have less protection to the sun's powerful ultra violet rays. The rays are reflected off the snow and hits the underside of your jaw. Don't forget to wear UV-rated goggles or sunglasses, as well.

- Know your 10 essentials when going on a hike, because cell phones won't always work in many rural areas, and may not be depended on in an emergency situation.

1. Navigation 2. Hydration & Nutrition 3. Pocket Knife 4. Sun Protection 5. Insulation 6. Fire! 7. Lighting 8. First Aid 9. Shelter 10. Whistle

There is significant illegal border crossing activity near Campo, California and throughout the first 30 or so miles on the PCT. You should avoid camping near the border, especially if you are traveling alone. In the southern segments especially there is a possibility of encounters with undocumented aliens and drug runners. While the US Border Patrol is familiar with the Trail route and water cache locations, Trail users should be prepared to provide identification.

- Do not leave vehicles at the Mexican border.

- Lock your vehicle, storing valuables and WATER out of sight.

- For safety reasons especially, please sign in and out at trailhead registers.