Advice for nervous flyers

Travelling by plane can be a scary experience for people of all ages and backgrounds, particularly if they've not flown before or have experienced loss of cabin pressure or another traumatic event. It is not something to be ashamed of: it is no different from the personal fears and dislikes of other things that very many people have. For some, understanding something about how aircraft work and what happens during a flight may help to overcome a fear which is based on the unknown or on not being in control. This article will seek to help you do that and help you to prepare for a trip by air.

It should be stated initially and clearly that accidents involving aircraft are extremely rare. It is this fact that makes the media coverage of such incidents so prevalent. Despite what you may think, air travel is the safest form of transportation available to the traveller besides high-speed rail: you are far more likely to be involved in an accident on your way to the airport than you are whilst in the air.

Airlines and pilots take safety very seriously - and even if they were minded to cut corners, they are tightly regulated by government agencies to ensure standards. Any pilot will not begin a flight if there is any doubt about the fitness of the aircraft or the weather - as the pilots' saying goes, "takeoff is optional, but landing is compulsory!"

Understand

- See also: Flight and health

- I can fly. I am not afraid. – The Charter Trip (1980), a classic in Swedish cinema

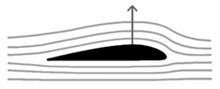

A rudimentary understanding of what causes your plane to fly can assist in allaying anxiety. A plane's wing is shaped to direct more air underneath it than above it, creating an area of low air pressure above the wing; this creates lift, causing an upward force on the wings. When the force of the lift exactly balances the weight of the aircraft, the plane will fly level; if the lift exceeds the weight, it will climb; and if weight exceeds lift, it will descend. Lift is proportional to airspeed: the faster a plane travels at a given altitude, the more lift its wings generate. So to make an aircraft climb the pilot increases the engine power; to make it descend, engine power is reduced. The shape of the wing can be altered using flaps (on the rear of the wing) and slats (on the front of the wing), allowing the aircraft to generate more lift at slower speeds, such as at takeoff and landing. These basic principles of physics are what underpin every flight. Unless there is a catastrophic failure of an aircraft's structure (which is extremely rare indeed), a plane cannot 'just fall out of the sky' any more than water can flow uphill.

Most aircraft, including all airliners (but not helicopters and some military jets), are also inherently stable. The forces acting on them - lift, weight, thrust and drag - tend to balance each other out, meaning the plane will fly straight and level unless the pilot does something to alter that. For instance, if the pilot increases power, the aircraft will climb; but eventually the speed will reduce, meaning lift will reduce, meaning the plane will level off. Even if the pilot let go of the controls altogether, the plane would eventually reach this straight-and-level equilibrium. There are limits beyond which the plane won't correct itself automatically, for instance, if it flies too slowly or climbs too steeply it will stall (meaning the wing no longer generates lift). A stall is perfectly recoverable, and are only deliberately created in testing new aircraft and training new pilots (so they can recognise the symptoms and learn how to react). All modern airliners have automatic systems which either alert the pilots to these situations well in advance, or stop them from happening altogether.

A typical flight

It might also help nervous flyers to understand what happens before and during a typical flight. All of these procedures are standard and extensively understood and practised by all pilots.

A lot of work goes into ensuring that flights are safe well before aircraft take off, and the aviation industry has a strong safety culture. The routes taken by commercial flights are typically planned by experts who seek to ensure that the flight is as safe and smooth as is possible. Pilots can amend these routes before take off and during the flight to further improve the comfort and safety of their passengers. The aviation industry is also highly regulated in the interests of safety. These regulations cover a very wide range of areas, including aircraft maintenance standards, requiring aircraft to carry more fuel than is required (so they can divert to another airport if needed) and making sure that pilots are well rested.

Commercial flights are guided throughout the journey by air traffic controllers on the ground, who ensure aircraft stay on course and remain well separated from each other (usually by several miles). Air traffic controllers also assist pilots with the safest and most comfortable journey from the moment the plane begins taxiing on the runway to the point when it arrives at the gate at which point passengers disembark.

A commercial aircraft has at least two people on the flight deck: the captain and the first officer. There may also be a second officer, and longer flights will have an additional captain and first officer to allow the first team time to rest. Like the captain of a ship, an airline captain has ultimate responsibility for the safety of the aircraft and everyone on board. The captain and first officer both "fly" the plane; to clarify responsibilities, one has the role of pilot flying and the other the role of pilot monitoring. The aircraft will have a number of flight attendants, at a minimum one for every 50 seats, who are responsible for safety in the cabin. The chief flight attendant is commonly known as the purser.

The following is based on a typical twin-engined jet aircraft, such as the Boeing 737 or the Airbus A320 family (the two most popular commercial aircraft models in service). There may be variations to this typical flight on other aircraft models, but the general sequence of events is the same.

Pre-flight

As passengers are boarding the aircraft, the pilots are on the flight deck making last-minute checks on the weather, departure procedures, and making sure the aircraft has enough fuel and isn't overweight. Once the doors are closed, you may hear a small jet engine powering up in the tail of the aircraft. This is the auxiliary power unit (APU), which provides power to the aircraft so the ground supply can be disconnected; it also supplies the compressed air needed to start the main engines. A tug will push the aircraft backwards out of the gate. When the aircraft is clear of the gate and the tug disconnected, the pilot will be given permission to start the main engines.

During pushback, a demonstration will take place to inform passengers of the safety features of the aircraft and their use. This may be given either by the flight attendants or through screening a video. A basic safety demonstration includes the use of the seatbelts, safely stowing luggage, use of the emergency oxygen masks, location and use of life jackets, emergency exit locations, a reminder that the flight is non-smoking, to put electronic devices in flight mode and turn them off for takeoff, and that further safety information can be found on the card in your seat pocket (or printed on the seats) or by asking a flight attendant. If you happen to be sitting in an exit row, you will also receive instructions from the flight attendants on how to operate the exit in case of an emergency evacuation.

Taxi

Before an aircraft can take off, it has to taxi (i.e. move on the ground under its own power) from the airport terminal to the runway. Aircraft always take off into a headwind, as this increases airspeed and so reduces the length of the take-off run, so the plane will taxi to the downwind end of the runway. At some small airports this may only take moments, but at larger ones, it can take several minutes. At one extreme, the far end of one runway at Schiphol Airport, Amsterdam is 9 km (5.6 mi) from the terminal and takes 15 to 20 minutes to taxi to and from. Aircraft move slowly on the ground with taxi speeds ranging from 10–40 km/h (6–25 mph).

During taxi, the pilots will deploy flaps and slats on the aircraft wings; the motors moving the flaps and slats make a distinct whining sound. In freezing temperatures, aircraft will need to be "de-iced" before reaching the runway. The plane will be sprayed with an anti-freeze solution to remove built-up snow and ice, as these can disrupt the airflow over the wings and reduce lift. Once in the air, the engines will provide hot air to prevent ice and snow from re-forming on the wings.

Take-off

.jpg)

When cleared for take-off, the pilot will taxi the aircraft into position at the start of the runway. It's normal for the pilot to increase engine power to ensure all engines are producing the same amount of power. Finally, the pilot will apply full take-off power; this usually means a rapid acceleration and increase in engine noise. When the aircraft has reached the correct speed (i.e., when it's travelling fast enough to generate the lift it needs to fly), the pilot will raise the nose and the plane will lift off from the runway. The speed required for take-off depends on the size and weight of the plane and weather conditions at the airport, but these factors are worked out precisely in advance. There is always enough runway left to complete the takeoff.

As the aircraft travels down the runway, you may hear and feel bumps as the aircraft's undercarriage crosses the runway lights or uneven parts of the runway. Such noises are to be expected and are not a cause for alarm. Equally, when the aircraft lifts off there is often a noticeable bump. This is a normal event caused by the hydraulics in the landing gear reaching their maximum extension as the plane leaves the ground.

On rare occasions, the pilots may decide to reject (abort) a takeoff, usually due to a fault with one of the aircraft's systems. The maximum speed to safely reject a takeoff, known as "V1", is precisely calculated before every flight. After an aircraft has passed V1, the pilot must take off or risk running off the end of the runway. If the fault is minor, the pilots may decide to continue the takeoff and come back around to land, since stopping at such high speeds within the remaining runway is very hard on the undercarriage and often results in overheating brakes and blown tires.

Climb

Once airborne and climbing, the pilot will raise the landing gear, which makes a bumping sound. Since full power is only needed for takeoff, the pilot will reduce power to the aircraft's engines and as a result, the noise in the cabin may decrease. The flaps and slats on the wings will also be retracted. It is also normal for planes to climb steeply and to turn, sometimes sharply, shortly after takeoff. These are standard procedures to turn the plane onto its course as soon as possible and to minimize noise for people living near the airport.

Depending on the length of the flight, it may then take 15-20 minutes for the plane to climb to its cruising altitude. The pilot will typically allow the flight attendants to leave their seats once the plane has cleared 10,000 feet (3000 meters) but it is common for the seat-belt light to remain lit for passengers until the plane reaches its cruise altitude. While the climb is often very smooth, occasional jolts (perhaps as the plane climbs through clouds) can still be expected.

Cruise

As it cruises, the plane rides upon an invisible cushion of air that has been pushed down by the shape of the wing. When there are bumps in this 'cushion' caused by gusts of wind, the plane may jolt slightly as it follows the shape of the air - this is turbulence. Turbulence may occur in both cloudy and clear skies and is completely normal; aircraft are designed to deal with these bumps and other than fastening your seat belt, there is no action that needs to be taken. Significant turbulence ahead can be detected on the plane's radar, and if it is the pilot will switch the seat belt sign back on. This may mean a very bumpy ride for a few minutes but there is no cause for alarm. If there is really severe turbulence ahead (for instance in thunder clouds) the pilot will normally divert around it. Some turbulence may cause the plane's wings to bend or flex a little: this is a deliberate design feature which actually allows the aircraft to withstand turbulence more effectively, just as a tree bends in the wind.

During cruise, the autopilot uses programmed instructions to fly the plane. The (human) pilots monitor the autopilot and make corrections to it as required.

Descent and approach

As the plane approaches its destination, it will begin to descend. The pilot will reduce engine power, sometimes so that the engines are only idling and barely making any noise. The steepness of this descent varies depending upon the airport and the aircraft. The pilot will typically switch the seat belt sign on as the aircraft begins to descend, although flight attendants won't typically be seated until the aircraft has descended through 10,000 feet (3000 meters). During the descent, the spoilers on top of the wings may open slightly; the spoilers decrease lift and act as brakes to prevent the aircraft from going too fast.

Aircraft always land into the wind, which helps slow the plane down. So depending on the direction from which you approach the airport, the plane may have to make a series of turns to line up with the runway. These are usually carried out at slow speed and can feel quite sharp as a result.

As the plane begins its initial approach into the airport, the pilots will deploy the flaps and slats on the wings; the flap motors make a distinctive whining sound. The flaps will be deployed in several stages and to a greater extent than at take-off. The pilots will also lower the landing gear; this makes a low thudding noise.

The approach to land can feel unstable. This is because the air near the ground is often more turbulent than it is at altitude. If there is a crosswind, the pilot may also have to bank and turn the aircraft slightly to keep it on course.

In some cases the aircraft will have to land in low cloud or fog, and you may not see the ground until you have almost landed. Most airports have instrument approach systems to help guide aircraft towards the airport and the runway; landings at major international airports with modern airliners can be safely conducted with as little as 50 m (150 ft) of visibility. But again, there are strict rules that pilots must (and do) stick to when landing in bad weather. If the weather is too bad, the pilot may decide to 'hold' (fly in circles) and wait for an improvement, or divert to another airport where the weather is better. All aircraft must carry at least enough fuel to fly to their destination, hold for up to 30 minutes and then divert to another suitable airport.

Landing

.jpg)

Just before the aircraft 'touches down' on the runway, the pilot flying will idle the engines and flare the aircraft by raising the nose, allowing the main landing gear to touch down first and take the weight of the aircraft before the nose landing gear touches down. The touchdown may be accompanied by a jolt and an audible 'thud' as plane's landing gear touches the ground. If the runway is wet, the pilot often lands deliberately firmly to minimize the risk of skidding. Spoilers on the wings will open to stop the aircraft generating lift and keep it firmly on the runway. To help slow the aircraft down, the pilot will engage reverse thrust: the direction of the engine's output is changed and the engines will power up again, slowing the plane down rather than pushing it forward. At some airports, the aircraft may slow down very sharply. This is simply to ensure it can turn off the runway at the right point, and/or means that there is another aircraft on the approach which needs to land.

In some rare cases, you may experience a go-around: when the aircraft takes off again just before landing. This occurs when the pilots decide to reject landing because of poor visibility, the aircraft is not in line with the runway or gets blown off course, or a runway obstruction. As a result, you will hear the engines power up once more and feel the engines' thrust to perhaps a greater degree than you did at take-off. The pilot will partially retract the flaps and raise the landing gear to help the aircraft climb. Once at a higher altitude and depending on the circumstances, the aircraft will either be turned around and the landing will be attempted again, or it will be diverted to another airport. Should this happen to you, you should not be alarmed - it is a common procedure and well-practised by pilots.

What if?

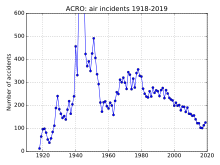

Every year, millions of flights take place without incident. The few serious aircraft accidents that do occur receive a large amount of media attention because they are so rare, along with media outlets' bias towards stories about death and disaster ("if it bleeds, it leads"). All serious accidents are thoroughly investigated by independent government bodies, such as the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) in the United States, to identify the cause and to prevent similar accidents occurring in the future.

Commercial aircraft are designed and tested to operate in conditions far more severe than those encountered on nearly any actual flight. For example, one test involves filling an aircraft with volunteers and testing whether the entire aircraft can be evacuated within 90 seconds with half the exits blocked and only emergency lighting. Aircraft are also maintained to strict and regular schedules. If any essential equipment on an aircraft has even minor problems, the plane is not allowed to take off until it is fixed. However, with all the precautions there is always a chance something may go wrong with the aircraft you are aboard. You should, however, be assured that pilots are trained (and refreshed regularly) on how to respond to common onboard emergencies, and quick reference guides in the cockpit are used to assist in responding to rarer issues. Every commercial aircraft is built with multiple redundancies and 'fail-safes', so in the case of one system failing, the aircraft can continue flying safely on the remaining systems. Even in the very rare case that all engines fail and can't be restarted, the pilots can glide the aircraft to a suitable landing place. The 1983 "Gimli Glider" (Air Canada flight 143; ran out of fuel due to metric/imperial conversion error) and the 2009 "Miracle on the Hudson" (US Airways flight 1549; engines flamed-out after ingesting a flock of geese) are both testaments that it is possible to do without fatalities or serious injuries.

If any foreseeable conditions arise that might endanger flights, chances are, flights are not even allowed to start or strict rules are put in place to avoid such an occurrence. A particular example of this was the 2010 eruption of the Eyjafjallajökull volcano in Iceland; volcanic ash has been known in the past to clog jet engines but never once caused any actual crash, even still all flights across Europe were grounded as a precaution. Likewise, when the Samsung Galaxy Note 7 smartphone was recalled in October 2016 after faulty batteries caused them to randomly explode, airlines and regulators were quick to ban the phone in any condition aboard aircraft.

Even with all the fail-safes and extensive flight training, pilot error is still the number one cause of aircraft accidents worldwide. To reduce the chance of errors, pilots use checklists to ensure they have done essential tasks, as well as using quick reference guides to handle onboard issues and emergencies. Pilots and air traffic controllers must have a good knowledge of the English language, and use standard vocabulary to communicate with each other to ensure there are no misunderstandings. A heavy emphasis in pilot training today is put on cockpit resource management (CRM), that is, the soft skills such as communication, decision-making, problem-solving and task-sharing needed to fly a commercial airliner and to effectively handle onboard emergencies. The introduction of CRM in the late 1970s to early 1980s was a large contributing factor in driving down the number of fatal airliner accidents, and variants of CRM have since been adopted for other modes of transport, firefighting and emergency healthcare.

There are extensive measures in place to prevent deliberate acts of sabotage on-board aircraft, such as hijackings and bombings. Metal detectors, X-ray machines and explosive detection dogs are all used to make sure that nothing dangerous can be taken aboard an aircraft. Governments and airlines also have no-fly lists to make sure that dangerous or potentially dangerous passengers cannot buy airline tickets and board an aircraft. Airport and airline staff also take aviation security seriously; all airport police carry firearms (even in countries where regular beat police officers are unarmed) and are not afraid to tackle a person to the ground and drag them away in handcuffs for something as simple as making a joke. Israeli aviation security is particularly thorough and enjoys a reputation for ruthless efficiency even though some question the means by which it is achieved. As a testament to this, Ben Gurion Airport is considered one of the safest in the world and flag carrier El Al has not had a successful hijacking since 1968 despite probably more attempts than at any other airline. Unlike most aviation security, the Israeli doctrine places great emphasis on finding the person who has bad intentions rather than the bomb itself. This still makes the line of questioning uncomfortable and somewhat intrusive, but it should assuage your concerns about safety and security.

Statistics

Commercial air travel is regarded as one of the safest forms of transport in the world. Every year, 3.8 billion passengers and 55 million tonnes of cargo travel by air around the world and arrive safely at their destinations.

In the ten years from 2008 to 2017, there were 1,410 hull loss accidents (i.e. an accident where the aircraft was damaged beyond economic repair) worldwide involving fixed-wing aircraft with six or more seats, yet from those accidents, only 8,530 people died. For comparison, an estimated 1.25 million people worldwide die from road accidents every year. Apart from one or two outlier years, both the number of airline accidents and deaths have been on a sustained downward trend since the mid-1990s.

In terms of flight stages, final approach and landing is the most common time for an accident to occur, with takeoff and initial climb being the distant second. However, accidents during landing and takeoff are the most survivable – they occur close to airports where the aircraft are already travelling low and slow and emergency services can respond with a moment's notice.

|

Sorry Raymond, Qantas has crashed The 1988 film Rain Man may have drawn attention to Qantas's fatality-free safety record, but they forgot to mention that the airline's record only applies to the jet era (i.e. 1958 onwards). The airline had several fatal crashes in its pre-jet days, the last occurring in 1951. Hawaiian Airlines and Finnair also have fatality-free records in the jet era, along with around 40 younger airlines. Of course, an airline's past accident record is not indicative of its future accident record. |

In the developed world, there is no statistically significant difference in accident rates between different airlines or between aircraft models of a similar era. Airlines from underdeveloped countries generally have poorer accident rates mainly due to poorer regulatory oversight. The European Union maintains a list of airlines banned from its airspace, a list which has a very low tolerance of even the appearance of systemic safety issues and which arguably includes a few airlines for nothing but political reasons.

Coping

This page has been created to provide helpful advice to those people who suffer from a fear of flying. There are many techniques for overcoming a fear of flying and many airlines, pilots, and therapists run courses for this purpose. Here is a selection of ways in which you might alleviate your anxieties.

Before the flight

Even before booking your ticket for a flight, it is worth considering how you will feel once on board. Some passengers prefer window seats whilst others prefer one towards the centre of the cabin. On large planes, however, a seat in the middle of a row could mean that you are several metres from a window to peer out of. Generally, the larger the aircraft that you are flying on, the smoother the flight will be, though factors such as storms will make even extremely large aircraft experience turbulence.

Some people are nervous flying on propeller-driven aircraft, thinking they are older or more dangerous. Most actually have turboprop engines - essentially a jet engine driving a propeller - and are just as modern and no less safe than jets. They are cheaper to operate on short journeys, although they are slower and often noisier.

Once your ticket is booked, it is well worth notifying your airline of your fear, both on the day of your flight and beforehand. Airlines work very hard to make their passengers feel safe and comfortable, and can do much to make you feel better.

Aboard the plane

Once you're aboard, it can be well worth having some form of distraction with you to avoid flying phobia. Many airlines offer in-flight entertainment systems, but books and magazines can also be good to take your mind off things. Sleep too can be a good way to pass the time whilst flying, although you are not advised to take any medication that may make you drowsy or sleepy. It is also ill-advised to counter your fear of flying with a large helping of 'Dutch courage': excessive alcohol or drug use normally causes more problems than it solves, and will often result in the aircraft diverting to a nearby airport and you being handed over to local law enforcement. Additionally, alcohol contributes to dehydration: your body already loses water faster than usual due to factors like dry cabin air and sweating. Resulting dehydration causes discomfort (dry eyes and throat is one example), so it's recommended to drink some water every now and then, and to be moderate with tea, coffee, and alcohol. If your vice is nicotine, note that smoking is banned on nearly all commercial flights worldwide. E-cigarettes (vaping) are also banned, but nicotine patches or chewing gum is generally allowed. Don't think you can get away with it; there are ultra-sensitive smoke detectors in the cabin and in all lavatories. On longer flights it's important to keep your circulation going: standing up, walking in the aisle, perhaps doing some simple stretching helps. However, walking around increases chances of injury during sudden clear air turbulence.

If you have any medical conditions, remember to keep to your regular routine as much as possible. Every year, hundreds of aircraft are needlessly diverted because a nervous passenger has forgotten to take their medications and is now in need of hospitalisation.

Try not to keep looking at your watch or a clock while flying. It will make the flight feel longer, especially on long-haul flights.

Turbulence

Turbulence is a completely normal part of flying. It can help to think of your plane as travelling along an invisible 'road' made of air and that the turbulence you feel is pot-holes in this 'road'. Turbulence can sometimes be unexpected and may vary from just a few minutes to throughout the whole flight. It is highly recommended you wear your seatbelt whenever you are seated, even if the fasten seatbelt sign is off, just in case of unexpected turbulence. Injuries and deaths from turbulence are rare, but all have resulted from unrestrained passengers and crew being flung around the cabin during unexpected severe turbulence.

Though turbulence is not in any way a threat to an airliner, turbulence feels like a threat to anxious fliers. This is because the amygdala, the part of the brain that releases stress hormones, reacts automatically to downward motion. If we were on a ladder painting the ceiling, lost our balance and began to fall, the amygdala would immediately release stress hormones to force us to shift our focus from painting to falling. In turbulence, stress hormones can be released each time the plane moves downward. As stress hormone levels rise, they cause physical sensations, such as rapid heart rate, breathing rate, tension, and perspiration, that are associated with danger. Thus, though the intellect may well understand that turbulence is not a danger, the emotional and physical state contradict the intellect. If stress hormones rise high enough, what psychological theoretican Peter Fonagy calls psychic equivalence takes place, causing the person to conflate what is imagination with what is perception. Imagination that the plane is "falling out of the sky" can, when stress hormones are high, become all too real to the fearful flier. Some are helped by conceptualizing how the plane is being held in the air as suggested in this video.

Noises

Like any large piece of machinery, an aircraft makes mechanical noises along with 'clunks' and 'thuds'. These are entirely normal and should be seen as a positive indicator - your plane is functioning correctly! Other sounds that you may hear are whining sounds, whistling sounds and loud banging sounds.

Airbus A320 and A330 families of aircraft are well known for producing a "barking dog" sound, especially during engine start-up and taxi. Again, this is completely normal - the noise comes from the power transfer unit (PTU), which equalises pressure between the aircraft's two engine-powered hydraulic systems when one engine isn't running (aircraft engines can only be started one at a time, and some airlines taxi on one engine to save fuel).

Turning

To turn an aircraft, the pilot cannot just use the rudder as you would in a boat. S/he also has to bank it - to raise one wing while lowering the other, making the aircraft turn in the direction of the lowered wing. This should be smooth and gentle, and the angle of bank doesn't normally exceed about 30 degrees.

Courses

As noted above, airlines, pilots, and psychologists offer programs for people who suffer a fear of flying. Some are listed below:

- Air France

- Anxieties.com

- Flying with Confidence - British Airways

- Fearless Flyers - QANTAS

- FearofFlying.com - SOAR, Inc..

- VALK - KLM

- Flying Without Fear - Virgin Atlantic