Zoara

Zoara, the biblical Zoar, previously called Bela (Genesis 14:8), was one of the five "cities of the plain"[1] – a pentapolis apparently located along the lower Jordan Valley and the Dead Sea plain and mentioned in the Book of Genesis. It was said to have been spared the "brimstone and fire" which destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah in order to provide a refuge for Lot and his daughters.[2] It is mentioned by Josephus;[3] by Ptolemy (V, xvi, 4); and by Eusebius and Saint Jerome in the Onomasticon.[4][5]

Owing to the waters coming down from the mountains of Moab, Zoara was said to be a flourishing oasis where the balsam, indigo, and date trees bloomed luxuriantly.[6]

In the Bible

Zoara, meaning "small" or "insignificance" in Hebrew (a "little one" as Lot called it), was a city east of Jordan in the vale of Siddim, near the Dead Sea. Along with Sodom, Gomorrah, Admah, and Zeboim, Zoar was one of the 5 cities slated for destruction by God; but Zoar was spared at Lot's plea as his place of refuge (Genesis 19:20-23). Segor is the Septuagint form of "Zoar". A Zoar is mentioned in Isaiah 15:5 in connection with the nation of Moab. This connection with Moab would be consistent with a location near the lower Dead Sea plain.

Other ancient references

Egeria the pilgrim tells of a bishop of Zoara that accompanied her in the area, in the early 380s. Antoninus of Piacenza in the 6th century describes its monks, and extols its palm trees.[6] [7]

The Notitia Dignitatum, 72, places at Zoara, as a garrison, the resident equites sagitarii indigenae (native unit of cavalry archers); Stephen of Byzantium (De urbibus, s.v. Addana) speaks also of its fort, which is mentioned in a Byzantine edit of the 5th century (Revue biblique, 1909, 99); near the city was a sanctuary to Saint Lot. mentioned by Hierocles (Synecdemus) and George of Cyprus.[8][9]

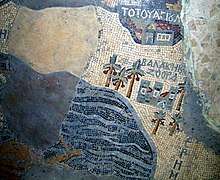

In the Madaba Map of the sixth century, it is represented in the midst of a grove of palm trees under the names of Balac or Segor.[10]

During the Crusader period it took the name of Palmer, or of Paumier. William of Tyre (XXII, 30) and Fulcher of Chartres (Hist. hierosol., V) have left descriptions of it, as well as the Arabian geographers, who highly praise the sweetness of its dates.[6] It is not known when the city disappeared;[9]

According to the 14th century travelogue The Travels Of Sir John Mandeville:

"Zoar, by the prayer of Lot, was saved and kept a great while, for it was set upon a hill; and yet sheweth thereof some part above the water, and men may see the walls when it is fair weather and clear."[11]

Bishopric

Zoara was part of the late Roman province of Palaestina Tertia.

It became a bishopric and is included in the Catholic Church's list of titular sees.[12]

Le Quien gives the names of three of its bishops;[13]

- Musonius, present at the Second Council of Ephesus (449) and the Council of Chalcedon (451);

- Isidore, mentioned in 518 when Isidore signed the synodal letter of Patriarch John of Jerusalem against Severus of Antioch.

- John, in 536 signed the acts of the synod of Jerusalem convoked by Patriarch Peter against Antime of Constantinople and saw the bishops of the Three Palestines together. In the same year, in May, John also took part in the synod of Constantinople by Patriarch Mena to condemn Antimo.

- An anonymous bishop is mentioned in the Itinera hierosolymitana of the end of the fourth century (Vailhé).

Catholic titular see

The Roman Catholic Church still recognizes the diocese of Zoara (in Latin: Dioecesis Zoarensis) as a suppressed and titular see of the Roman Catholic Church, in Jordan, though the seat is vacant since August 25, 2001. Known Catholic bishops include:

- Francesco Maria Cutroneo (March 15, 1773 – November 1780)

- José Nicolau de Azevedo Coutinho Gentil (July 18, 1783 – 1807)

- Jean-Henri Baldus, (March 2, 1844 – September 29, 1869)

- Claude-Thierry Obré (December 14, 1877 – December 14, 1881)

- Pedro José Sánchez Carrascosa y Carrión (March 30, 1882 – 1896)

- Patrick Vincent Dwyer (January 30, 1897 – July 9, 1909)

- René-Marie-Joseph Perros, (September 17, 1909 – November 27, 1952)

- Antonio Capdevilla Ferrando (March 24, 1953 – August 12, 1962)

- Wacław Skomorucha (November 21, 1962 – August 25, 2001)

Other references to Zoara

The Syriac Chronicles of Michael the Syrian (12th century) and of Bar Hebraeus (thirteenth century) contain some obscure traditions regarding the founding of some of the "cities of the plain". According to these accounts, during the lifetime of Nahor (Abraham's grandfather), a certain Canaanite named Armonius had two sons named Sodom and Gomorrah, for whom he named two newly built towns, naming a third (Zoara) after their mother.

Zoara is not mentioned in the Ebla tablets though there has also been some conjecture that Admah, with which it biblically tied, is mentioned in the Ebla tablets.[14]

Archaeology

Prior to the major archaeological excavations in the 1980s and 1990s that took place in Zoara, scholars proposed that several sites in the area of Khirbet Sheikh 'Isa and al-Naq' offered further evidence of Zoara's location and history. Further information regarding Zoara in different historical epochs were obtained through the descriptions of Arabian geographers, suggesting that Zoara served as an important station in the Aqaba-to-Jericho trade route, and through Eusebius' statement that the Dead Sea was situated between Zoar and Jericho. Researchers who have studied ancient texts portray Zoara as a town erected in the middle of a flourishing oasis, watered by rivers flowing down from the high Moab Mountains in the east. The sweet dates that grew abundantly on the palm trees surrounding Zoara are also mentioned in some historical texts.

Several excavation surveys have been conducted in this area in the years 1986-1996. Ruins of a basilical church that were discovered in the site of Deir 'Ain 'Abata ("Monastery at the Abata Spring" in Arabic), were identified as the Sanctuary of Agios (Saint) Lot. An adjacent cave is ascribed as the location where Lot and his daughters took refuge during the destruction of Sodom. About 300 engraved funerary steles in the Khirbet Sheikh 'Isa area in Ghor as-Safi were found in 1995. Most gravestones were inscribed in Greek and thus attributed to Christian burials, while several stones were inscribed in Aramaic, suggesting that they belong to Jewish burials. Of these, two inscriptions reveal the origins of the deceased as being Jews that hailed from Ḥimyar (now Yemen) and are funerary inscriptions dating back to 470 and 477 A.D., written in the combined Hebrew, Aramaic and Sabaean scripts. In one of them it was noted that the deceased was brought from Ẓafār, the capital of the Kingdom of Ḥimyar, to be buried in Zoar.[15] These gravestones have all been traced back to the fourth-fifth centuries A.D., when Zoara was an important Jewish center. Unusually, Christians and Jews were buried in the same cemetery.[16]

See also

- Admah - one of the five "cities of the plain"

- Sodom and Gomorrah - two of the five "cities of the plain"

- Zeboim - one of the five "cities of the plain"

References

| Wikisource has the text of the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia article Zoara. |

- Genesis 14:2-8

- Genesis 19:22-30

- Ant. Jud., XIII, xv, 4; Bell. Jud., IV, viii, 4

- Eusebius (2006) [manuscript, 1971]. Wolf, Carl Umhau (ed.). THE ONOMASTICON OF EUSEBIUS PAMPHILI, COMPARED WITH THE VERSION OF JEROME AND ANNOTATED. tertullian.org. Zeta, in Genesis.

Zogera (Zogora).467 In Jeremia. City of Moab. It is now called Zoora or Sigor (Segor), one of the five cities of Sodom.

- Eusebius (1904). Klostermann, Erich (ed.). Das Onomastikon der Biblischen Ortsnamen. Die griechischen christlichen Schriftsteller der ersten drei Jahrhunderte (in Greek and Latin). Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs. 94-95. OCLC 490976390.

- Guy Le Strange, Palestine under the Moslems, 289

- Egeria, The Pilgrimage of Etheria, trans. M. L. McClure and C. L. Feltoe (London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1919), 20, 23–24.

- Description of the Roman World

- "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Zoara". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 2018-02-12.

- Herbert Donner, The Mosaic Map of Madaba. An Introductory Guide, Palaestina Antiqua 7 (Kampen: Kok Pharos, 1992), 37–94; Eugenio Alliata and Michele Piccirillo, eds., The Madaba Map Centenary: Travelling Through the Byzantine Umayyad Period. Proceedings of the International Conference Held in Amman 7–9 April 1997, Studium Biblicum Franciscannum Collectio Maior 40 (Jerusalem: Studium Biblicum Franciscannum, 1999), 121–24

- Mandeville, John (1900). The Travels Of Sir John Mandeville. Macmillan. p. 40.

- Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2013, ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 1013

- Le Quien, Michel (1740). "Ecclesia Zoarorum sive Segor". Oriens Christianus, in quatuor Patriarchatus digestus: quo exhibentur ecclesiæ, patriarchæ, cæterique præsules totius Orientis. Tomus tertius, Ecclesiam Maronitarum, Patriarchatum Hierosolymitanum, & quotquot fuerunt Ritûs Latini tam Patriarchæ quàm inferiores Præsules in quatuor Patriarchatibus & in Oriente universo, complectens (in Latin). Paris: Ex Typographia Regia. cols. 737–746. OCLC 955922748.

- Thomas O'Toole, Ebla Tablets: No Biblical Claims Washington PostDecember 9, 1979

- Naveh, Joseph (1995). "Aramaic Tombstones from Zoar". Tarbiẕ (Hebrew) (64): 477–497. JSTOR 23599945.; Naveh, Joseph (2000). "Seven New Epitaphs from Zoar". Tarbiẕ (Hebrew) (69): 619–636. JSTOR 23600873.; Joseph Naveh, A Bi-Lingual Tomb Inscription from Sheba, Journal: Leshonenu (issue 65), 2003, pp. 117–120 (Hebrew); G.W. Nebe and A. Sima, Die aramäisch/hebräisch-sabäische Grabinschrift der Lea, Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy 15, 2004, pp. 76–83.

- Yael Wilfand (2009). "Aramaic Tombstones from Zoar and Jewish Conceptions of the Afterlife". Journal for the Study of Judaism. 40: 510–539. doi:10.1163/157006309X443521.