Zitacuaro Council

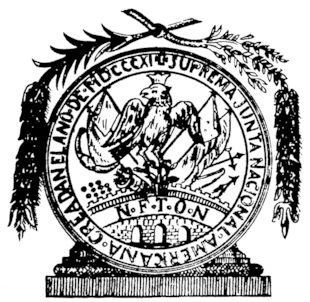

The Zitacuaro Council, also known under a variety of names such as the Supreme National American Meeting or Supreme Governmental Board of America, was a council established by insurgent leaders Ignacio López Rayón and José María Morelos, along with minor members José María Liceaga and José Sixto Verduzco, which would serve as a prototypical government independent of the Spanish crown.

The council was established 19 August 1811.

Founders

Ignacio López Rayón

Ignacio López Rayón and José María Liceaga were originally part of Miguel Hidalgo's insurgent forces that initiated the first phase of the Mexican War of Independence. After a crushing defeat in the Battle of Calderon Bridge, the diminished insurgent forces fled north hoping to attain military and economic support from the United States. While en route north, López Rayón stayed behind in Saltillo, Coahuila with 3,500 men and 22 cannons. He eventually heard of the capture of Hidalgo and other insurgent leaders and decided to flee south on 26 March 1811. Encountering and battling royalist forces various times during his route south, he eventually reaches Zitacuaro, Intendancy of Valladolid (present-day Michoacan).

José María Morelos

During Miguel Hidalgo's march towards Mexico City, his former student, José María Morelos, finds him while stationed in Valladolid (present-day Morelia). Morelos wished to join Hidalgo's forces but Hidalgo suggested to him to create another insurgent army in the south and to capture the port city of Acapulco, a strategic location where the Manila Galleons would deliver goods from the Philippines, then a Spanish domain under the vice-regal structure of New Spain.

His first campaign would take place in the southern portions of the neighboring intendancies of Valladolid, Mexico, and Puebla (present-day Guerrero). Shortly after the end of his first campaign, he received an invitation from Ignacio López Rayón to organize an insurgent assembly since after the capture and death of the first leaders, the insurgent forces were dispersed and without a visible general head.[1] Written on July 13, 1811, Morelos would accept the invitation but would send José Sixto Verduzco as his representative as he was away fighting. [2]

History

As president of the council, López Rayón attained the title of "Universal Minister of the Nation and President of the Supreme Council," the only one to ever hold such position. He coordinated the creation of the newspaper El Ilustrador Nacional, by Andrés Quintana Roo and José María Cos, to disseminate the ideas of the insurgency. Rayón did not succeed in getting the heads of the different armed factions to recognize the authority of the council, therefore, he cited to swear in the governors and mayors of the neighboring towns.[3]

During existence of the council, the first draft of the national constitution was composed, the Constitutional Elements; the first stamp of Mexican coins was made; as well as the first attempts to obtain the recognition of the international community through the sending of an ambassador to the United States, Francisco Antonio de Peredo y Pereyra.[4]

The creation of the council drew the attention of the viceregal government and General Felix Maria Calleja, publishing a proclamation on 28 September 1811 from Guanajuato,[5] ignoring the council, threatening to advance on Zitácuaro and putting a price on Rayón's head: ten thousand pesos.[6]

When these strategies failed, the royalists hired a person named J. Arnoldo to assassinate Rayón, but he was discovered and executed.[7][8]

General Calleja attacked Zitacuaro in the early days of January 1812 and makes the insurgent forces and the council flee Zitacuaro on 11 January 1812. From there, the assembly was relocated to various cities under insurgent control: Tuzantla, Tlalchapa, and Sultepec.[9][10]

Despite being the first governmental body that represented areas liberated of Spanish control, it was unable to exercise any administrative power effectively as in theory it appointed local authorities to towns and municipalities under its jurisdiction. However, this task almost always fell on the military leaders who had conquered places that were outside their domain and pursued their own goals.[11] Ineffectiveness to project administrative power, coupled with López Rayón's military loses, led to the eventual replacement of the governmental body by the Congress of Chilpancingo.

References

- José Valero Silva (1967). "Proceso moral y político de la Independencia de México". Estudios de Historia Moderna y Contemporánea de México Vol. 2. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

- José María Morelos y Pavón (13 August 1811). "José María Morelos escribe a don Ignacio López Rayón, brindándole su apoyo entusiasta para la instalación de la Suprema Junta Gubernativa". 500 años de México en Documentos. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- Zárate, Julio (1880). «La Guerra de Independencia». En Riva Palacio, Vicente. México a través de los siglos III. México: Ballescá y Compañía. Consultado el 2 de mayo de 2010.

- Zárate, Julio (1880). «La Guerra de Independencia». En Riva Palacio, Vicente. México a través de los siglos III. México: Ballescá y Compañía. Consultado el 2 de mayo de 2010.

- Zárate, Julio (1880). «La Guerra de Independencia». En Riva Palacio, Vicente. México a través de los siglos III. México: Ballescá y Compañía. Consultado el 2 de mayo de 2010.

- Herrejón Peredo, Carlos (1985). La Independencia según Ignacio Rayón (PDF). Cien de México. Biblioteca Digital Bicentenario (1ª edición). México: Secretaría de Educación Pública. ISBN 9682905338. Archivado desde el original el 19 de enero de 2010. Consultado el 25 de abril de 2010.

- Herrejón Peredo, Carlos (1985). La Independencia según Ignacio Rayón (PDF). Cien de México. Biblioteca Digital Bicentenario (1ª edición). México: Secretaría de Educación Pública. ISBN 9682905338. Archivado desde el original el 19 de enero de 2010. Consultado el 25 de abril de 2010.

- Zárate, Julio (1880). «La Guerra de Independencia». En Riva Palacio, Vicente. México a través de los siglos III. México: Ballescá y Compañía. Consultado el 2 de mayo de 2010.

- Carabes Pedroza, Jesus et al. Historia Activa de Mexico. Mexico D.F.: Editorial Progreso S.A. de C.V. 1972.

- Villaseñor y Villaseñor, Alejandro (1910). «Ignacio Rayón» (PDF). Biografías de los héroes y caudillos de la Independencia. Biblioteca Digital Bicentenario. México: Imprenta “El Tiempo” de Victoriano Agüeros. Archivado desde el original el 25 de junio de 2009. Consultado el 25 de abril de 2010.

- Carabes Pedroza, Jesus et al. Historia Activa de Mexico. Mexico D.F.: Editorial Progreso S.A. de C.V. 1972.