Zhu Dehai

Zhu Dehai (Chinese: 朱德海; Korean: 주덕해; March 5, 1911 – July 3, 1972) was a Korean Chinese revolutionary, educator, and politician of the People's Republic of China. He served as a political commissar of the Eighth Route Army during the Second Sino-Japanese War. Later he became the first governor of Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture and was in office from 1952 to 1965. He also served as the member of the National People's Congress (NPC) for several years. He is known as a political moderate and defied orders from the party during the Great Leap Forward while maintaining a close relationship with North Korean government. His affiliation with the North Korean leadership eventually led him to downfall. During the Cultural Revolution, the Red Guards stigmatized Zhu as a North Korean spy, an accusation that expelled him from all political positions.

Zhu Dehai | |

|---|---|

朱德海 | |

| |

| 1st Governor of Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture | |

| In office 2 September 1952 – 18 April 1967 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Wu Jishe (Alias Zhu Dehai) 5 March 1911 Dobea, Gorod Ussuriysk, Russian Empire |

| Died | 3 July 1972 (aged 61) Wuhan, Hubei, China |

| Nationality | Chinese |

| Political party | Communist Party of China |

| Spouse(s) | Jin Yongshun (Kim Youngsun) |

| Alma mater | Communist University of the Toilers of the East |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | People's Republic of China |

| Branch/service | Eighth Route Army |

| Years of service | 1939–47 |

| Rank | Political Commissar |

| Battles/wars | World War II, Chinese Civil War |

As a Korean minority high-ranking cadre, he contributed to improve the social status of Korean minority in China. His support for Korean's autonomy in northeastern China culminated in the establishment of Yanbian Korean autonomous prefecture in 1952. He also paid attention to the education for Korean Chinese. When he was in Yan'an, he was one of the founder of the Military and Political University for Korean Revolution (Chinese: 朝鲜革命军政大学; Korean: 조선혁명군정대학). He also played a crucial role in the establishment of Yanbian University, the first university in Yanbian prefecture.

Born as the son of a poor Korean farmer who immigrated to the Primorsky Krai region of Russian Empire in 1911, he developed into an ardent communist, studying in a local school ran by a Korean communist group. As a member of Chinese Communist Party, he took part in a series of guerrilla activities against the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931. In 1935, following party's order, he went to Moscow to study at the Communist University of the Toilers of the East and graduated in 1938.

Later he joined Yan'an’s Chinese Communist Party headquarters, and undertook a position in the education department for the Korean Chinese minority in China. In October 1945, after the defeat of Japan in the Second World War, Zhu led a vanguard army to claim the former Manchurian territory. During the Chinese Civil War, he led the organization of a voluntary battalion of Korean communists and occupied Harbin along with the People's Liberation Army. Zhu's prominence, formerly not conspicuous in the party, emerged dramatically by virtue of his exploit in the northeastern province during the Chinese Civil War.

In 1949, shortly before the foundation of the People's Republic of China, Chinese Communist Party appointed him as the first secretary of the Yanbian Local Committee of the Communist Party, which represented the whole Korean minority in northeastern China. His career among the Korean minority culminated in power in 1952 as he was inaugurated as the first governor of the freshly established Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture. Simultaneously, he enjoyed the elevation of political influence in the central politics of China. In 1954, he was appointed as the vice governor of Jilin Province and elected as the first member of the National People's Congress. He had served as the member of the Committee for three periods in a row until the Cultural Revolution.

In 1966, Zhu became the target of criticism by the Red Guards in Yanbain province. Mobilized by Mao Yuanxin, a cousin of Mao Zedong, Red Guards condemned him of treason. Also, the Red Guards accused him of the “Top Capitalist” in the province. He resigned from the seat in 1966 and sent down (Pinyin: xiafang) to Hubei province. He died there from lung cancer in 1972.

After the demise of Mao and the subsequent downfall of the Gang of Four, Zhu Dehai was posthumously rehabilitated officially in 1978. In 2007, his remains buried in Wuhan were sent back to Yanji.

Early life

Zhu Dehai was born Oh Giseop (Chinese: 吴基涉; Korean: 오기섭) in a small Korean settlement called Debea (Chinese: 道別河; Korean: 도별하) located in Gorod Ussurysk, Primorsky Krai region of the Russian Empire in March 1911.[1] His father, Oh Wooseo, born in Hoeryong, a border city in Korea, immigrated to Primorsky Krai across the Russo-Korean border during the great famine in 1902. His hometown, Dobea, approximately 50 Kilometers from Ussuriysk, was a small settlement established by immigrated Korean farmers like the Oh family. Oh Wooseo was a poor tenant farmer working in a remote valley from the village, and the father of two children. Zhu was the youngest in the Oh family.

When Zhu was seven years old, his father was killed by a robber known as a Chinese national.[2] In the absence of the breadwinner, Zhu and his brother, led by their mother, Ms. Heo, came back to his father's hometown, Hoeryong, in October 1918.[3] Two years later, the family again crossed the border, this time toward the Jiandao region of the northeastern China, the most popular destination for Korean immigrants during the Japanese occupation of Korea. Zhu's family settled in a Korean immigrant's town called Sudong'gol (present-day Guang Xin Xiang, Longjing, Jilin), where one of Zhu's uncle had a farm.[4]

In Sudong'gol, Zhu enrolled in the Fourteenth Public Elementary School of Helong County, run by the Republic of China's local government. According to the biography on Zhu written by Korean Chinese writers, including his spouse, Gin Yongshun, Zhu's revolutionary and nationalistic consciousness was greatly inspired by a class he took on the Xinhai Revolution and Sun Yat-sen at the school.[5] He graduated elementary school in Winter 1922. However, due to poverty he had to stop learning at an advanced school in order to support the family.

Early Revolutionary Activity

Communist Education

Working as a laborer in Longjing for several years, Zhu came to be aware of the conflict between the Japanese and the Korean minorities in Jiandao. In 1927, Zhu became a student of a private school owned by Kim Kwangjin, a Korean communist who was prominent among the locals.[6] Driven by Korean nationalism and the ideal of the communist revolution inspired by Kim, he joined the Communist Youth League of Korea (Korean: 고려공산주의청년동맹) in 1929.[7] This organization was affiliated with the Korean Communist Party, an underground party illegalized by the colonial government of Korea. Zhu's responsibility in the organization was delivering secret messages among the members, those who were looking for a way to smuggle firearms to Korea.

Organizing Communes

In February 1930, Zhu decided to live the life of a devoted revolutionary after leaving his family at home. He joined a team of communists who planned to build a base for an upcoming communist's revolution in Ning'an, Heilongjiang Province.[8] In Ning'an, Zhu settled in a farm house in the vicinity of the urban area, where his comrades stored rifles in secret. In August, according to the Comintern's new guideline, "One nation, One Party," he switched from the Communist Youth League of Korea to Communist Youth League of China.[9] Later in 1930, the Communist Party of China Harbin branch delivered an order to Zhu's organization to prepare a riot early the next year.[10] However, in November, the Republican authorities revealed the riot and most local cadres were arrested. In the midst of chaos, Zhu managed to escape from the scene and found refuge on a nearby mountain.[11]

In January 1931, Zhu left his shelter and settled in a village called Chengzicun (Chinese: 城子村) near Jingpo Lake, under an alias. There, in May 1931, he was named by the party as secretary of the village, in recognition of his contribution to the building of a commune. At the same time, the party granted him membership of the Chinese Communist Party.[12]

Partisan Activity during the Japanese Invasion

On 19 September 1931, the Imperial Japanese army invaded northeastern China. As the nationalist government withdrew from the region to avoid confrontation, the Chengzicun commune became occupied by the Japanese army by late September. Shortly after the Japanese invasion, Zhu and his communist colleagues fled to Mishan, Heilongjiang, which was yet to be overrun by the Japanese army.[13] The local committee of the party in Mishan sent Zhu to Errenbanxiang, a small town in the southern vicinity of Mishan, to build a revolutionary base in the village.[14] He worked for the party in Errenbanxiang, forming a sham marriage with one of his comrades to avert suspicion from the Japanese patrols and pro-Japanese local authorities by 1934.

Japanese army seized Mishan in May 1932. In a protest against the Japanese occupation, Zhu organized an anti-Japanese mass rally in October 1932. However, he was caught at the scene of the protest. When a group of policemen investigated him, he used the alias Zhu Dehai. It was the first time he used this alias and he continued to used this alias from since then. During the investigation, he denied the accusation that he was the mastermind of the rally and finally was discharged.[15] In Spring 1934, in order to break away from the Japanese surveillance, Zhu moved his base to a mountain slope near the River Hada (Simplified Chinese: 哈达河), along with approximately twenty guerrilla members. Dwelling a year at a secret base on the mountain, even suffering from tuberculosis, he trained approximately one hundred guerrillas.[16] These guerrillas later constituted the third battalion of the Northeast Anti-Japanese United Army, a partisan army fought against the Japanese puppet regime of Manchukuo.

Activities during the Sino-Japanese War

Education in Moscow and Yan'an

As Zhu could not afford to work at the front due to his worsening illness, the party decided to send him to Moscow for treatment and cadre education.[17] In Summer 1936, unknown to him where he was destined, Zhu crossed the Russo-Manchurian border to go to Vladivostok. Subsequently, he rode on the train heading for Moscow. The party enrolled him in the Communist University of the Toilers of the East in late 1936. At first, he enrolled in the course for Chinese students but subsequently switched to the Korean course.[18] During the coursework, he studied the basic theory of Marxism–Leninism, history of the communist movement, and military strategy. At the university, he was also acquainted with other Chinese cadres, such as Kang Sheng, who later accused Zhu as a traitor of the party during the Cultural Revolution.[19]

Zhu and his cohort graduated the course in Summer 1938. After a year of travel from Moscow via Xinjiang, Zhu finally arrived in Yan'an. The Chinese Communist Party ordered him to study further at the Counter-Japanese Military and Political University so that the party could send him back to work in northeastern provinces. At the school, he studied with notable Korean communists such as Zu Chungil (who later became the North Korean ambassador to Moscow), Kim Changdeok (who later became the commander of the Fifth Division of the Korean People's Army). He graduated the course in Winter 1938.[20]

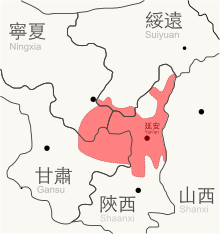

Eighth Route Army

In Winter 1938, the party cancelled its plan to send Zhu to the northeastern front, due to the impending Japanese offensive toward Yan'an. Zhu was alternatively assigned to the 718th Regiment of the Eighth Route Army.[21] For three years, he served as a political commissar in the regiment, dispatched in Nanniwan of Shaan-Gan-Ning Border Region, a small village approximately thirty kilometers away from Yan'an. According to a biography on Zhu, he also participated in the Yan'an Rectification Movement, while it is still unknown what part he took charge in during the movement.[22] In 1942, the party sent him to Yan'an again to enroll in an advanced education course for high-ranking cadres. During the course, he researched on how Marxism–Leninism can be applied to Chinese specific case. Also, he befriended Zhu De, Hu Yaobang, and Zhou Enlai in Yan'an, who later supported Zhu's political stance in Yanbian.[23]

Education for Korean Communists

In 1943, after his graduation, the party ordered Zhu to establish a cadre school for the education of Korean communists in order to train Korean cadres. This school, later called Military and Political University for Korean Revolution (Simplified Chinese: 朝鲜革命军政大学; Korean: 조선혁명군정대학) was established by Zhu and other high-profile Korean communists, such as Kim Tu-bong, and trained about 200 graduates, those of whom later formed the Yan'an Faction, a group of Pro-Chinese communists in North Korea. Zhu took charge of the management of the school until the defeat of the Japanese Empire.[24]

Korean Minority Leadership

Chinese Civil War

After the end of the Second World War, the United States and the Soviet Union occupied Korea. While many Korean communists returned to an independent Korea, which they assumed would soon be unified, Zhu expected that the division of Korea would be perpetual. Hence, he believed that Korean communists in the CCP should rather take over former Manchurian territory in which more than a million of Korean minorities were residing. Once the communist party occupies the northeast, then communists could recruit and train a Korean army that could consolidate the divided Korea.[25]

Followed by Zhu, about 300 Korean communists left Yan'an for the northeastern provinces to take over the former Japanese territory in late August.[26] In the northeast, Zhu played a leading role in the organization of a voluntary battalion, in which he took charge as the political commissar. His voluntary battalion, commanded by Lee Sangjo (who later became the vice chief of staff of the Korean People's Army), engaged in several battles with National Army and finally seized Harbin on April 28, 1946.[27]

Staying in Harbin, Zhu met and married his wife, Gin Yongson (Korean: 김용순) in Spring 1947. In the meantime, he dispatched several troops to the countryside where the Korean population was prevailing, in order to accelerate the land reform. His decision derived from the legislation of the Chinese Agrarian Law on October 10, 1947. Despite resistance from the landlords that involved violence, Zhu carried out the land reform. As a result, the communist party could distribute 75.7ha of lands to Korean minorities.[28] Zhu also took control of formerly Japanese-owned factories left behind after the defeat. He ordered to run the factories and exported manufactured products to North Korea. The trade between the northeastern provinces and North Korea contributed to the military campaign of the party in the northeastern theater.[29]

In 1948, the Chinese Communist Army named Zhu as the Ethnic Affairs Minister (Simplified Chinese: 民族事务处长), the position that administered all the minority issues of the whole northeastern provinces.[30] He particularly invested in the education and cultural programs for the Korean minority. During his tenure, he established several civil and cadre schools in order to train Korean bureaucrats to work for the party.[31] He also established the Yanbian University in 1949 and was inaugurated as the first president of the university.

Establishment of Autonomous Prefecture

By 1949, the communist's victory in the civil war became irreversible. As the foundation of a new communist Republic of China was being discussed, Korean minority leaders and North Korean leaders privately, if not entirely confidential, began to debate the future of Korean minority in the northeastern provinces. In November 1948, an official delegation that consists of Korean minority leaders visited Pyongyang. In a meeting with the delegation, Kim Chaek, the vice chancellor of North Korea, claimed the sovereignty of Yanbian region. It is still unknown that how Zhu responded it, but Lim Chunchoo, the acting secretary of Yanbian, was inclined to Kim's claim reportedly.[32] While the official biographies on him denied his collusion with the North Korean leaders, Zhu at least promised to support the North Korean regime during his visit in North Korea, according to an article reported by Daily Yanbian on December 1, 1948.

“The delegation of Korean Chinese of Northeastern China visiting North Korea to celebrate the foundation of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, had toured and experienced the new democracy across the field of industry, economy, education and the culture. They were also impressed by how our democratic fatherland is going forward to the rich and powerful country by the hand of the patriotic people. The head the delegation, Mr. Zhu Dehai stated that “Looking at the gleaming flag of the people's republic, we … appreciate our glorified nation that performs the historical mission given to us.” In addition, he pledged that he and overseas Korean will bring an honor to the revolutionary tradition and the glory of Korean nation perpetually.”[33]

_September_21%2C1949.jpg)

When Zhu came back to China, however, he overturned the stance toward the relationship with the North Korea. In a meeting on the ethnic issues in January 1949, Zhu repudiated Lim's support for the North Korean annexation of the Yanbian region, backing the autonomy plan.[34] According to historian Yeom In-Ho, this meeting was decisive to the career of these two Korean minority leaders; Zhu proved that he was a credential minority leader committed to the Chinese Communist Party while Lim's affiliation with the North Korean leaders was seen as sectarianism.[35] Eventually, Lim was removed from all title and later expelled to North Korea. On the other hand, the communist party, facing a crucial battle in Shenyang against the nationalist army in earlier 1949, should approve the autonomy to secure the support from the Korean minority and to stabilize the home front in the northeast. As a result, Zhu was appointed as the secretary of Yanbian province in February 1949, and subsequently named as the first governor of the Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture, in September 1952. However, several cadres were discontent on the party's decision. Some political opponents persistently accused of Zhu's alleged pledge to North Korea, questioning the loyalty of Zhu even until the Cultural Revolution.[36]

Anti-Rightest Movement and Backlash

Background

In 1956, Mao encouraged intellectuals to discuss the current problem of Chinese society, and even allowed them to criticize the party and the regime (the Hundred Flowers Campaign). This movement boosted a wide range of criticism of the ethnical supremacy of Han Chinese and their chauvinism among the minority intellectuals by earlier 1957. However, in April 1957, Mao abruptly stopped the movement, criticizing the liberal intellectuals. Instead, he instigated the Anti-Rightest Movement (Simplified Chinese: 反右运动) that purged the intellectuals who took part in the criticism against the regime. Along with liberal intellectuals, minority intellectuals who raised issues of ethnic inequality were also targeted by the Anti-Rightist Movement.

Movement in Yanbian

In Yanbian province, the Chinese Communist Party Yanbian Committee led by Zhu held several meetings in response to the Anti-Rightest Movement. This meeting embraced Scholars, Artists, and leading figures in the cultural and industrial fields. In a series of meetings, Korean leaders sympathized with the Korean minority's sentiment over nationalism issues. For example, in a meeting, Zhu mentioned that “Korean Chinese people pretend that China is their fatherland. However, especially among the older generation over forty, they do not consider themselves as Chinese. When they come across a trouble, they tend to miss Korea more in particular.” Other participants, such as Lee Shousong mentioned in a bolder tone, saying, “Korea is not simply a foreign country for Korean minority; Korea is the “national fatherland (Chinese: 民族祖国).”” However, no matter what was discussed in the meetings, Zhu and Yanbian Committee finally agreed to perform a rectification movement as ordered from Beijing.[37] The movement aimed to attack three rightest tendencies: bureaucratism, sectarianism, and subjectivism. Zhu led self-criticism of the rightest tendencies among the cadre group in a series of symposiums in order to expand the scale of the movement throughout the prefecture. As a result, Jung Kyuchang, a renowned doctor at Yanbian Medical School, Writer Choi Jungryeon, and other prominent scholars and artists were ousted from their positions and prohibited from publication as they were stigmatized as rightests.[38]

Criticism toward Zhu

The Anti-rightest movement provoked an unprecedented criticism toward the high-ranked party officials and bureaucrats including Zhu. The main criticism came from Jin Minghan (Korean: 김명한), the vice secretary of the Yanbian Committee. He was the first leading cadre who raised the issue of the “provincial nationalism (Chinese: 地方民族主义).” Contrary to sympathetic attitude toward Korean nationalism among the cadres, he denounced “some Korean nationalists” for attacking the party and the regime to protect their personal and national interest. To defend the party from these sectarianists, he argued that the Korean Chinese cadres should comply with the course of the Proletariat Nationalism, the official stance of the Party on ethnic issue.[39]

At first, it was a self-criticism by the local cadres that consolidated unity among the cadres as well as an oath of allegiance to the Communist Party. However, combined with the Anti-Rightest Movement, the anti-provincial nationalism developed into a political slogan evoked by Jin's argument. From the early 1958, Zhu and high cadres were condemned by a group of students at Yanbian University, being accused of nurturing Korean nationalism. By their hands, more than 45,000 wall newspapers accusing local cadres of being “provincial nationalists” were displayed on the campus wall of Yanbian University from April to May in 1958. One of the wall newspaper condemned Zhu and another vice governor Li Haoyuan for their alleged claim that all Korean minority population in northeastern China should be governed by the Autonomous government.

During the movement, Zhu withheld to take an action against the movement, waiting for the situation to calm down. Having a turbulent period for a couple of months, the anti-rightest movement finally blew over in late 1958. Zhu and high cadres in Yanbian prefecture managed to maintain their position with impunity, despite of strong demand to resign. However, it culminated in the abolishment of the Ethnic Education Agency of Jilin province, established by Zhu himself. As a result, five Korean and one Mongolian officials, allegedly being “provincial nationalists”, at the Ethnic Education Agency was purged as the protesters demanded. Consequently, Korean minority's nationalism was officially denied by the leading cadres of Yanbian, and call for more autonomous right was strictly restricted.

Great Leap Forward

Politburo Meeting

In earlier 1958, a mass mobilization plan to raise up productivity in a short term, later known as the Great Leap Forward, was adopted by the Central Committee of the Communist Party. The party established a model commune at Chayashan in Henan Province, where private plots were entirely abolished, and commune members were enforced to dine at a communal kitchen. On August 13, 1958, Chairman Mao delivered an order to apply this model commune across the country.[40] In August 1958, at a Politburo meeting, where Zhu also attended as the representative of Yanbain prefecture, Mao adopted an ambitious plan to surpass the UK's steel production within 15 years. According to the biography on Zhu, he was skeptical as to whether the goal of the Great Leap Forward is feasible, although he agreed to the means of the movement such as the backyard furnace.[41] However, he could not conflict with the decision from the Central Committee. Once he came back to Yanbian, he ordered to establish an experimental commune in Longjing, Jilin. Subsequently, the commune system entirely substituted the collective farms in Yanbian within one month. As a result, 921 collective farms were consolidated into 78 communes, encompassing 172,388 households. Also, the possession of farm equipment, livestock, and orchard tree, formerly owned privately, were all vested to the commune.[40]

Productivity Improvement Movement

The commune system of Yanbian changed the lifestyle of people entirely. First of all, the communal kitchen was introduced. However, Zhu disapproved to run the communal kitchen all year round, suggesting three reasons below at a cadre meeting.

“First, given the long and harsh winter in the Northeastern province, the households in Yanbian should stoke a hypocaust (ondol) in winter no matter where they eat. In winter season, therefore, it will be a waste of firewood if we stoke a communal kitchen and a domestic hypocaust simultaneously. Second, a collective meal for hundreds of workers could not satisfy everyone’s appetite. In fact, people are already cooking leftovers again at home. Lastly, it became harder to feed a domestic pig and a dog. Before the communal kitchen, farmers fed leftovers to the pigs and dogs. Now, farmers should find another way to feed their pigs and dogs."[42]

In 1957 winter, he finally persuaded the cadres to stop running the communal kitchen. However, other movements mobilizing the mass, in the name of the “New mode of production movement (Chinese: 新的生产高潮),” were beyond the control of the local cadres in Yanbian. For example, during the Deep Plowing movement (Chinese: 深耕高潮), Jilin province allocated a production quota to its subordinate prefectures, including Yanbian, and expelled a cadre if his prefecture did not meet the quota allocated.[43] According to the biography on Zhu, he felt reluctance to encourage the Deep Plowing movement, but was afraid of being criticized as a rightest in the aftermath of the Anti-Rightest movement.

Besides, a quota on steel and irrigation construction was also allocated from the Jilin Provincial party. At first, Zhu was optimistic about the steel production plan, because it had been his long dream to make Yanbian self-sufficient in steel production in Yanbian.[44] In Yanbian prefecture, many communes built hundreds of backyard furnaces, mobilizing around 9,000 of workers, but the result was not as good as local cadres expected.[45] In 1958, Zhu admitted his misjudgment and closed the whole furnaces.

Cultural Revolution and Downfall

"Fatherland" Question

Ethnic minorities in China struggled with how to define their own nationality since the late nineteenth century, when the idea of nationalism first introduced in China. The "Fatherland" (Chinese: 祖国; Pingying: Zǔguó) question, or the nationality question, was particularly raised in the 1920s, along with the arrival of Marxism–Leninism. In 1925, Lenin published his thoughts about the liberation of oppressed nations, writing:

"Victorious socialism must achieve complete democracy and, consequently, not only bring about the complete equality of nations, but also give effect to the right of oppressed nations to self-determination, i.e., the right to free political secession."[46]

Lenin's thesis cast a question to some Han chauvinists and minority leaders on whether the ethnic minorities in China should claim independence. During the Yan'an period, however, Mao Zedong concluded that all Chinese people are part of the "mighty Zhonghua nation (Chinese: 伟大的中华民族)."[46] With respect to Korean minority, Mao specifically mentioned, writing:

"China borders ... Korea in the east, where she is also a close neighbor of Japan... China has a population of 450 million, or almost a quarter of the world total. Over nine-tenths of her inhabitants belong to the Han nationality. There are also scores of minority nationalities, including the Mongol, Hui, Tibetan, Uighur, Miao, Yi, Chuang, Chungchia and Korean nationalities... All the nationalities of China have resisted foreign oppression and have invariably resorted to rebellion to shake it off... Thus the Chinese nation has a glorious revolutionary tradition and a splendid historical heritage... The contradiction between imperialism and the Chinese nation and the contradiction between feudalism and the great masses of the people are the basic contradictions in modern Chinese society... the contradiction between imperialism and the Chinese nation is the principal one.[47]

Mao and CCP believed that this discourse of the unitary nation could consolidate the Han nation and the other ethnic minorities in China during the War against Japan.[48]

The discourse of unitary nation was, however, unacceptable to most of the Korean minority population. Koreans believed that their status was different from other minorities in China. That is, while other minorities were indigenous for generations in China, Korean minorities immigrated very recently. Therefore, many of Korean minorities assumed that their "Fatherland" is North Korea until the 1950s. In 1948, the communist party even acknowledged that the status of Korean minorities was a special case. The Yanbian committee of the party announced that "the Party will admit that this nation [Koreans] is a minority that belongs to another "fatherland."[49] On the other hand, Zhu officially embraced the "big family nation" advocated by Han-dominant party cadres, and that Korean minority is part of the big family, namely the Zhonghua nation.[30] However, a few people were discontent with Zhu's point of view. Some Korean nationalists brought up the theory of "Multi-Fatherland." It explained that the Korean minority, in the light of its historical experience, has three "Fatherlands;" first, North Korea, the national Fatherland; second, USSR, the fatherland of the proletariat class, and lastly, China, the third "fatherland" where they live now. Some of the Han population was also discontent with Korean leadership in Yanbian. They believed that Zhu's policy was too skewed toward the Korean minority's interest. This ethnic conflict turned out to be the primary factor behind the political turmoil during the Cultural Revolution.

Rebellion in Yanbian

In May 1966, Mao launched the Cultural Revolution. In Yanbian, the revolution was prompted by Korean minority students studying in the other parts of northeastern provinces. These students were inspired by the ideal of the Cultural Revolution at their universities and came back to Yanbian to spread the revolution in their hometown. They rallied at Yanbian University in August 1966 and formed a rebel group called "8. 27 rebels." This rebel group was a far-leftist group that consists of Korean students emphasizing Maoist theory. The other students who did not agree with the "8. 27 rebels" organized another rebel group, "Hongqi Zhandou Lianjun (The United Army of the Red Flag; Simplified Chinese: 红旗战斗联军)." By the end of 1966, these two rebel groups struggled to win the support of the public.[50] According to the biography, Zhu asked them to return to school, but rebel students defied Zhu's proposal. The rebels said that they were in Yanbain at the request of Jiang Qing, one of the Gang of Four, as well as the then-first lady of China. Later, the rebels also accused Zhu of defying the order of Jiang Qing.[51]

In January 1967, as Mao Yuanxin, a cousin of Chairman Mao, delivered an order to rebel groups, the Cultural Revolution in Yanbian entered its second phase. At that time, Mao Yuanxin was leading a series of attacks toward cadres of the party in northeast provinces. He announced that the criticism of rebels should be toward the corrupted cadre, Zhu Dehai. Mao also argued that the success of the Cultural Revolution in Yanbain rested upon whether the rebels could overthrow Zhu Dehai or not. Driven by Mao's announcement, the rebels denounced him by delivering a public speech and distributing pamphlets. The most notable pamphlet was the one published in the mid-1967. This pamphlet was an outcome of an investigation against Zhu and his close cadres.[52]

Pamphlet Incident

In 1967, the rebel group in Yanbian published a pamphlet that accused Zhu as a traitor, a Korean nationalist, and a spy from North Korea. The relationship between China and North Korea was worsening during the Cultural Revolution as Maoists condemned North Korean leader Kim Il-sung as a revisionist. Given this context, the accusation that stigmatized Zhu as a North Korean spy also implied that Zhu followed Kim Il-sung's revisionist line defying the orthodox Maoist dogma of the CCP.

The accusation of this pamphlet was based on Zhu's statement in the late 1940s. First, the pamphlet accused him as an agent of Kim Il-sung, the leader of North Korea. For example, the pamphlet, quoting the aforementioned Daily Yanbian article, argued that Zhu's mention about "Fatherland" (refer to the underlined part) is the proof that he is a North Korean agent.[53] The pamphlet also condemned Zhu for violating the Mao's discourse of "mighty Zhonghua nation," saying, "Senile old man Zhu Dehai attempted to segregate Korean minorities from the big family of Zhonghua nation."[54]

This pamphlet also alleged that the then-leadership of the North Korea was plotting the annexation of Yanbian province. For example, this pamphlet quoted Kim Il-sung's statement at a meeting with Zhu in 1948, that "All Yanbian's [Korean] minority should serve their genuine "Fatherland," North Korea." According to the pamphlet, Zhu accepted Kim's order and had played a secret agent role for North Korea by now.[55] The pamphlet also attributed the large number of Chinese defectors who escaped to North Korea in the 1960s, as many as 28,000, to the Zhu's deliberate scheme.[56] The pamphlet concluded that Zhu conspired to establish an "independent [Korean] nation" in Yanbian and to dedicate the Yanbian territory to North Korea in near future. The rebels pasted this his pamphlet on walls of streets in major cities of Yanbian. This pamphlet incident played a decisive role in the downfall of Zhu.

Deportation and Death

Even before the Pamphlet Incident, Zhu was under house arrest by rebels since the conflict with Mao Yuanxin in early 1967. During the confinement, cadres of the People's Liberation Army negotiated with rebels to save him from house arrest. The army officials managed to save him from the house, but he was still confined in a hospital under the surveillance of Red Guards. During the Pamphlet Incident, the local committee of the communist party decided to deport him from Yanbian, not only because of the pressure of rebels but also for his security.

April 18, 1967, the party first sent him to Beijing for his safety. In Beijing, he reportedly worked with other deported high-ranking cadres in a farm. In September 1969, the party sent him to a countryside town near Wuhan. It is still not clear who was responsible for this decision. He was forced to work in a farm with other farm workers, concealing his former position and name. Since his deportation from Yanbian, he had suffered from respiratory disease, which later turned out to be lung cancer. On July 3, 1972, he died from lung cancer at a hospital in Wuhan.

References

- Kang, Changrok (2001). Zhu Dokhae. Seoul: Silchon Munhaksa. p. 17.

- Kang. Zhu Dokhae. p. 20.

- Kang. Zhu Dokhae. p. 21.

- Kang. Zhu Dokhae. p. 22.

- Kang. Zhu Dokhae. p. 24.

- Kang. Zhu Dokhae. pp. 32–33.

- Kang. Zhu Dokhae. p. 39.

- Kang. Zhu Dokhae. pp. 53–54.

- Kang. Zhu Dokhae. p. 56.

- Kang. Zhu Dokhae. p. 58.

- Kang. Zhu Dokhae. pp. 64–66.

- Han, Junkwang (1990). Jungguk Josonjok Inmuljon. Yanbian: Yanbian People's Press. p. 506.

- Kang. Zhu Dokhae. pp. 75–76.

- Kang. Zhu Dokhae. p. 76.

- Kang. Zhu Dokhae. pp. 87–89.

- Kang. Zhu Dokhae. pp. 92–101.

- Kang. Zhu Dokhae. p. 103.

- Kang. Zhu Dokhae. p. 104.

- Kang. Zhu Dokhae. p. 106.

- Kang. Zhu Dokhae. p. 116.

- Kang. Zhu Dokhae. p. 117.

- Han. "Inmuljon". p. 508.

- Kang. Zhu Dokhae. p. 118.

- Kang. Zhu Dokhae. pp. 119–124.

- Yeom, Inho (2010). Tto hanaŭi han'gukchŏnjaeng. Seoul: Yŏksabip'yŏngsa. p. 8.

- Kang. Zhu Dokhae. p. 127.

- Kang. Zhu Dokhae. p. 137.

- Kang. Zhu Dokhae. pp. 141–143.

- Kang. Zhu Dokhae. p. 150.

- Han. "Inmuljon". p. 512.

- Kang. Zhu Dokhae. pp. 153–156.

- Yeom. "Han'gukchŏnjaeng". p. 194.

- Yeom, Inho (2005). "chungguk yŏnbyŏn munhwadaehyŏngmyŏnggwa chudŏkhaeŭi silgak". Journal of Korean Independence Movement: 406–407.

- Han. "Inmuljon". pp. 511–513.

- Yeom. "Chungguk". p. 206.

- Yeom. "Chungguk". p. 207.

- Chongch'ŏl, Pak (2015). "Chunggugŭi minjokchŏngp'ungundonggwa chosŏnjogŭi puk'anŭroŭi iju". Korean Journal of Social Science. 35:2: 162.

- Kang. Zhu Dokhae. pp. 244, 246.

- National Institute of Korean History. "Chaeoedongp'osach'ongsŏ". National Institute of Korean History.

- Chungguk Chosŏn Minjok Palchachʻwi Chʻongsŏ Pʻyŏnjip Wiwŏnhoe (1993). P'ungnang. Beijin: Minjok Ch'ulp'ansa. p. 181.

- Wang, Tŭk-sin (1988). Chu Tŏk-hae ŭi ilsaeng. Yanbian: Yŏnbyŏn Inmin Ch'ulp'ansa. p. 280.

- Kang. Chu Tŏk-hae ŭi ilsaeng. pp. 283–284.

- Chungguk Chosŏn Minjok Palchachʻwi Chʻongsŏ Pʻyŏnjip Wiwŏnhoe. P'ungnang. p. 182.

- Chungguk Chosŏn Minjok Palchachʻwi Chʻongsŏ Pʻyŏnjip Wiwŏnhoe. P'ungnang. p. 286.

- Chungguk Chosŏn Minjok Palchachʻwi Chʻongsŏ Pʻyŏnjip Wiwŏnhoe. P'ungnang. p. 183.

- V. I. Lenin. "The Socialist Revolution and the Right of Nations to Self-Determination". www.marxists.org. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- Mao, Zedong. "THE CHINESE REVOLUTION AND THE CHINESE COMMUNIST PARTY". www.marxists.org. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- Leibold, James (2007). Reconfiguring Chinese Nationalism: How the Qing Frontier and Its Indigenes Became Chinese. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 102.

- Yeom. "Chungguk". Journal of Korean Independence Movement: 408.

- Yeom. "Chongguk". Journal of Korean Independence Movement: 397–400.

- Kang. Zhu Dokhae. pp. 270–271.

- Yeom. "Chongguk". Journal of Korean Independence Movement: 6–7.

- Yeom, Inho (2005). "chungguk yŏnbyŏn munhwadaehyŏngmyŏnggwa chudŏkhaeŭi silgak". Journal of Korean Independence Movement. 25: 405.

- Yeom. "Chungguk". Journal of Korean Independence Movement: 407.

- Yeom. "Chungguk". Journal of Korean Independence Movement: 412–417.

- Yeom. "Chongguk". Journal of Korean Independence Movement: 429–430.