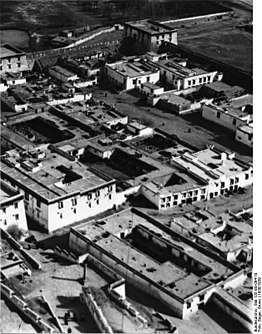

Zhol Village

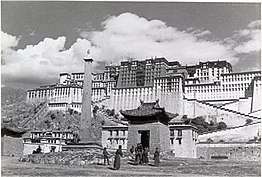

Zhol Village or Shol Village (often transcribed as Shöl or Zhöl Village) was a small village at the base of the Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet.

Zhol, means 'below' in Tibetan, and refers particularly to a village or town right below a mountainside castle. Zhol City (Xuecheng), also known as "Snow City", is located on the lower boundary of the Potala Palace entrance.

The present, largely reconstructed, Zhol City covers 50,000 sq m. of the Potala Palace complex. It includes of 22 ancient buildings which cover an area of 33,470 sq m. These buildings once included housing as well as the city jail and government offices (for the city's administration, judiciary, revenue, and mint).

The buildings of Zhol City also include a Treasure Hall, Western Sutra Printing House, and Relics of Granary. The six remaining buildings (including the city towers) are not expected to be opened to the public.[1]

.jpg)

Zhol contained the graceful stone pillar, the Lhasa Zhöl rdo-rings or Lhasa Zhol Pillar, also known as the Doring Chima,[2] which dates as far back as circa 764 CE, "or only a little later,"[3] and is inscribed with what may be the oldest known example of Tibetan writing.[4]

It includes an account of the Tibetan campaigns against China which culminated in the brief capture of the Chinese capital Chang'an (modern Xian) in 763 CE[5] during which the Tibetans temporarily installed as Emperor a relative of Princess Jincheng Gongzhu (Kim-sheng Kong co), the Chinese wife of Trisong Detsen's father, Me Agtsom.[6][7]

Footnotes

- "Potala Palace, Lhasa, Tibet". The Internet Archive. 2016-06-23. Archived from the original on 2016-06-23. Retrieved 2017-12-15.

- Larsen and Sinding-Larsen (2001), p. 78.

- Richardson (1985), p. 2.

- Coulmas, Florian (1999). "Tibetan writing". Blackwell Reference Online. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- Snellgrove and Richardson (1995), p. 91.

- Richardson (1984), p. 30.

- Beckwith (1987), p. 148.

References

- Alexander, André (2002). "Zhol Village and a Mural Painting in the Potala: Observations Concerning Tibetan Architecture." Tibet Journal. Winter 2002, Vol. 27 Issue 3/4, p111, 12pp.

- Ancient Tibet: Research Materials from the Yeshe De Project. (1986). Dharma Publishing. Berkeley, California. ISBN 0-89800-146-3.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (1987). The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia. Princeton University Press. Princeton, New Jersey. ISBN 0-691-02469-3.

- Larsen and Sinding-Larsen (2001). The Lhasa Atlas: Traditional Tibetan Architecture and Landscape, Knud Larsen and Amund Sinding-Larsen. Shambhala Books, Boston. ISBN 1-57062-867-X.

- Richardson, Hugh E. (1984) Tibet & Its History. 1st edition 1962. Second Edition, Revised and Updated. Shambhala Publications. Boston ISBN 0-87773-376-7.

- Richardson, Hugh E. (1985). A Corpus of Early Tibetan Inscriptions. Royal Asiatic Society. ISBN 0-947593-00-4.

- Snellgrove, David & Hugh Richardson. (1995). A Cultural History of Tibet. 1st edition 1968. 1995 edition with new material. Shambhala. Boston & London. ISBN 1-57062-102-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shol. |

- Potala Palace

- "The Battle of the Barkhor". Gordon Laird - "Barkhor Heritage 05".

- Photo by Hugh Richardson 1949-50