Zheng Pingru

Zheng Pingru (1918 – February 1940) was a Chinese socialite and spy who gathered intelligence on the Imperial Japanese Army during the Second Sino-Japanese War. She was executed after an unsuccessful attempt to assassinate Ding Mocun, the security chief of the Japanese puppet government. Her life is believed to be the inspiration for Eileen Chang's novella Lust, Caution, which was later adapted into the eponymous 2007 film by Ang Lee.

| Zheng Pingru | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 鄭蘋如 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 郑苹如 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Early life

Zheng Pingru was born in 1918.[1] She was a native of Lanxi, Zhejiang Province.[2] Her father, Zheng Yue (鄭鉞), also known as Zheng Yingbo (鄭英伯), was a Nationalist revolutionary and a follower of Sun Yat-sen. While a student in Japan, Zheng Yue married a Japanese woman, Hanako Kimura (木村花子), who adopted the Chinese name Zheng Huajun (鄭華君).[3] They had two sons and three daughters; Pingru was the second oldest daughter.[4]

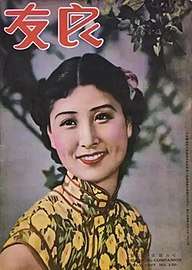

From her mother, Zheng Pingru learned to speak Japanese fluently.[5] She grew up in Shanghai, where her father taught at Fudan University.[4] She studied at the Shanghai College of Politics and Law, and performed with a group of actors from Datong University.[5] She became a well-known socialite and appeared on the cover of the popular pictorial The Young Companion (Liangyou) in 1937.[6] Although her family was half-Japanese, they were strongly opposed to Japan's aggression toward China. When Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931 and attacked Shanghai in 1932, Zheng and her siblings joined anti-Japanese protests.[4]

Wartime spy

When Japan invaded China in 1937 and occupied Shanghai following the Battle of Shanghai, Zheng secretly joined the resistance movement and became an underground Kuomintang (Nationalist) spy.[7] Her ability to speak Japanese and the connections to her mother helped her to spy on and collect information on the Japanese Army.[2]

Zheng was involved in a plot to assassinate Ding Mocun, the security chief of the Japanese puppet regime headed by Wang Jingwei.[7] Ding was hated for collaborating with the Japanese and gained the nickname "Butcher Ding" for executing anti-Japanese resistance fighters. As Ding had formerly served as the principal of Zheng's secondary school, she was tasked with seducing him and luring him into a trap.[4][6] In 1939, Zheng arranged several "chance" encounters with Ding, and became his girlfriend.[6]

On 21 December 1939, Zheng accompanied Ding to dinner at his friend's house. After the dinner, Zheng requested Ding to drop her off at Nanjing Road, Shanghai's famous shopping street. When the car drove by the Siberia Fur Company, Zheng said she wanted to buy a fur coat and asked him to help her choose one. Two Kuomintang assassins had been waiting nearby for a chance to kill Ding. While inside the store, Ding grew suspicious when he saw the men outside, and abruptly ran across the street to his car. Caught off guard, the assassins shot at Ding, but missed him before his driver sped away.[3][4]

After the failed attempt, Zheng's cover was blown and she was arrested and held at Ding's intelligence headquarters at 76 Jessfield Road.[2][3] In February 1940, she was executed near Zhongshan Road in western Shanghai, at the age of 22.[2]

Legacy

The Kuomintang government in Taiwan formally declared Zheng a "martyr",[8] and the Communist Party of China called her an "anti-Japanese heroine".[7] A memorial with a statue of Zheng was unveiled in Qingpu, Shanghai in 2009.[9]

Zheng's story is generally believed to have inspired the character of Wang Jiazhi (Wong Chia-chih) in the novella Lust, Caution, written by Eileen Chang in 1979.[10][11] Chang had learned about Zheng from her ex-husband Hu Lancheng, who served as a propaganda official in the Wang Jingwei regime.[4]

In 2007, the novella was made into a film, Lust, Caution, directed by Ang Lee.[10] In the novel and the film, Wang Jiazhi's assassination plot failed because she had fallen in love with her target. There was protest in the way that Wang Jiazhi was depicted since it was felt that her story "perversely twisted the heroic deeds of her prototype, Zheng."[7] The Zheng family in particular felt that character based on Zheng dishonored her memory.[12]

Family

After Zheng Pingru's execution, her father soon fell ill and died in 1941. Her brother, Zheng Haicheng (鄭海澄), was a fighter pilot in the Republic of China Air Force who died in battle on 19 January 1944.[4] Her fiancé, Colonel Wang Hanxun (王漢勛), also a pilot who fought alongside her brother, was killed in action near Guilin on 7 August 1944.[3][8] Her mother later moved to Taiwan and died in 1966 at the age of 80.[4]

References

- Merkel-Hess, Kate (2018). "Women Warriors and Wartime Spies of China by Louise Edwards (review)". Twentieth-Century China. 43 (1): E-1–E-2. doi:10.1353/tcc.2018.0006. ISSN 1940-5065.

- "Zheng Pingru". Humanism Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- 《色戒》女主角原型鄭蘋如 美女間諜為國犧牲. Apple Daily. 5 July 2014. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- Ma 2017, p. 278.

- Edwards 2016, p. 142.

- Lin, Yingjun (13 June 2016). 她為抗日色誘漢奸 被槍殺時說了一句話. China Times (in Chinese). Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- Yang 2012, p. 191.

- Edwards 2016, p. 147.

- Edwards 2016, p. 154.

- Thompson, Zoë Brigley (2016). "Beyond Symbolic Rape: The Insidious Trauma of Conquest in Marguerite Duras's The Lover and Eileen Chang's "Lust, Caution"". Feminist Formations. 28 (3): 1–26. doi:10.1353/ff.2016.0041.

- Peng & Dilley 2014, p. 58.

- Lin, Chen (14 September 2007). "The Real Story Behind Lust, Caution Revealed". www.china.org.cn. Archived from the original on 26 October 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

Sources

- Edwards, Louise (2016). Women Warriors and Wartime Spies of China. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-14603-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ma Zhendu (2017). 國民黨特務活動史 [History of Kuomintang Intelligence Activities]. Jiuzhou Publishing House. ISBN 978-957-563-025-6.

- Peng, Hsiao-yen; Dilley, Whitney Crothers (2014). From Eileen Chang to Ang Lee: Lust/Caution. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-91102-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Yang, Haosheng (Fall 2012). "Myths of Revolution and Sensual Revisions: New Representation of Martyrs on the Chinese Screen". Modern Chinese Literature and Culture. 24 (2): 179–208. JSTOR 42940562 – via JSTOR.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)