Halabiye

Halabiye (Arabic: حلبيّة, Latin/Greek: Zenobia, Birtha) is an archaeological site on the right bank of the Euphrates River in Deir ez-Zor Governorate, Syria. It was an ancient city and former bishopric known as Zenobia and a Latin Catholic titular see.

حلبيّة | |

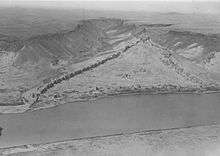

Aerial photo of Halabiye with the Euphrates visible in the lower part of the image | |

Shown within Syria | |

| Alternative name | Latin/Greek: Zenobia, Birtha |

|---|---|

| Location | Syria |

| Region | Deir ez-Zor Governorate |

| Coordinates | 35.689444°N 39.8225°E |

| Type | Fortified town |

| Area | 12 hectares (30 acres) |

| History | |

| Founded | 3rd century AD |

| Periods | Roman, Byzantine, Ayyubid? |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1944, 1945, 1987, 2006–2009 |

| Archaeologists | J. Lauffray, S. Blétry |

| Condition | Ruinous |

| Management | Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums |

| Public access | Yes |

Halabiye was fortified in the 3rd century CE by Zenobia, Queen of Palmyra, after whom the site was named in Antiquity. After her revolt against the Roman Empire in 273, Halabiye was captured by the Romans and subsequently refortified as part of the Limes Arabicus, a defensive frontier of Roman Syria to protect the region mainly from Persia. The site occupies an area of 12 hectares (30 acres), protected by massive city walls and a citadel on top of a hill. Remains of two churches, a public bath complex and two streets have been excavated. These all date to the reign of Byzantine Emperor Justinian I, who refortified the city in the 6th century AD.

History

Ancient era and Middle Ages

Halabiye site was already mentioned in the 24th century BCE archives found at Ebla. At that time, the site was known as Halabit. Zalabiye, on the oppose bank of the Euphrates, may have been known as Šalbatu. Halabit appeared on a list of cities that delivered tribute to Ebla. Given that it was the most southern city on this list, it has been suggested that the fortress may have been on Ebla's territorial boundary with its primary rival, Mari.[1] In Neo-Assyrian sources, the toponym Birtu appears, which may be synonymous to the Birtha of the classical period, suggesting that the site was also occupied during the Neo-Assyrian period (934–608 BCE).[2]

Halabiye experienced its heyday during the Roman and Byzantine periods. Before the site was incorporated into the Palmyrene Empire, it was a Roman garrison town known as Birtha. It was taken over by Palmyra in the 3rd century CE because of its strategic location on the river where it flows through a narrow gap. According to Procopius, the city was named after the Palmyrene queen Zenobia (240–274).[3] Halabiye was captured by the Romans in 273 CE during the war that broke out after Palmyra had asserted its independence from Rome. The fortress may have been repaired under Emperor Diocletian (244–311), who tried to strengthen the Limes Arabicus north of Palmyra, and again during the reign of Anastasius I (430–518). Emperor Justinian I (483–565) refortified Halabiye toward the end of his reign as part of his program to strengthen the border with the Sassanid Empire in the east.[2][4]

The earliest description is found in the De Aedificiis ("On Buildings") by Procopius, who described the fortress in the 6th century CE. Upon archaeological investigation of the site, Procopius’ description turned out to be highly accurate, suggesting that he knew the site from personal observation. Sasanian general Shahrbaraz captured the city in 610 during the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628.[3]

After the Muslim conquest of northern Mesopotamia, the need to maintain a well-defended border along the Euphrates disappeared. The citadel on top of the hill continued to be in use to control movement in the middle Euphrates area, and was heavily modified.[4]

Modern era

Halabiye has drawn the attention of European travelers and scholars since the mid-19th century. The English explorer Gertrude Bell passed the site on her travels in northern Mesopotamia and it was photographed by the French aerial archaeology pioneer Antoine Poidebard in the 1930s.[2][5]

In 1944 and 1945, the site was investigated by the French archaeologist Jean Lauffray, who drew maps and studied the ramparts and the public buildings. His team included 45 workers who were hired from a local Bedouin tribe. The team was allowed to use the tents and other necessary equipment from the German archaeological mission to Tell Halaf under Max von Oppenheim, which were placed in storage in 1939. In 1945, the excavation ended abruptly after unrest among the Bedouin workers, and the foreign team members left for Aleppo.[2]

Some of Lauffray's results were further corroborated during investigations at the site in 1987. A joint Syrian–French mission was initiated in 2006 by the Syrian Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums (DGAM) and the Paul Valéry University from Montpellier in France. The mission was led by Sylvie Blétry. After an initial survey mission in 2006, three excavation and restoration seasons took place between 2007 and 2009. Apart from a renewed investigation and mapping of the public buildings and ramparts, the Syrian–French mission also excavated areas with residential architecture. During the 2009 season, the necropolis was also mapped, resulting in the discovery of more than 100 new tombs.[6]

Description

Halabiye is located on the right bank of the Euphrates 45 kilometres (28 mi) upstream from Deir ez-Zor at a strategic location where basalt outcrops force the river through a narrow gap. These outcrops are locally known as al-khanuqa or "the strangler". The Wadi Bishri runs along the south side of Halabiye and this route toward the desert in the west is therefore also controlled by the fortress. Some 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) downstream lies the contemporary but smaller fortress of Zalabiye.[4]

The currently visible remains primarily date from the Byzantine occupation of the site. Halabiye is shaped like a crooked triangle with the east side parallel to the river bank of the Euphrates and the west corner on top of a hill with deep wadis on its north and south sides. The site is protected by massive walls that enclose an area of 12 hectares (30 acres). The walls on the north and south sides are largely intact, while only remnants of the east wall are still visible.[4] The east and west walls are still standing to elevations between 8 and 15 metres (26 and 49 ft).[2] The east wall facing the river, also built to protect the town against flooding, is 385 metres (1,263 ft) long and was pierced by three gates. The north wall runs from the river to the citadel on the top of a hill. It is 350 metres (1,150 ft) long, protected by five towers and pierced by a gate with two towers close to the river bank. Halfway up the slope of the hill lies the praetorium, a massive, square, three-storey building incorporated in the city wall that served as barracks. The south wall runs from the citadel down to the river. It is 550 metres (1,800 ft) long, guarded by ten towers and pierced by a gate similar to that in the north wall. All towers were built according to the same plan: square and with two storeys. They were accessible through covered galleries in the curtain walls and through stairways.[4]

The citadel occupies an east–west orientated, elongated area of 45 by 20 metres (148 by 66 ft) on the top of a rocky hill. The citadel consists of two different parts: a polygonal curtain wall with flanking towers in the east and a massive rectangular building in the east. The second structure is similar to the praetorium lower on the slope of the hill. In both parts, Roman, Byzantine and Arabic masonry has been identified.[2]

The site is divided in quarters by a colonnaded north–south street connecting the gates in the north and south walls and by a second street running east–west. Northwest of where the streets cross was the forum; northeast of this crossing was a public bath complex. Two churches have been located: a large church located in the northwest quarter of the town built during Byzantine Emperor Justinian I's reign and a smaller one located in the southwest quarter that was built slightly earlier.[4]

In the area north of Halabiye, along the Euphrates, is a cemetery with numerous tower tombs and rock-cut tombs. These structures date to the late Roman period and show clear cultural influences from Palmyra. Another necropolis was located south of the city.[4][7]

In the absence of a nearby community that could quarry Halabiye for building materials after it was deserted, the site has primarily suffered from earthquakes and its fortifications have survived largely intact.[4] The proposed construction of the Halabiye Dam on the Euphrates south of Halabiye will lead to the partial flooding of the site by the dam's reservoir. The Syrian government works together with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and UNESCO to reduce the impact of these construction works on the site.[8]

Ecclesiastical history

Zenobia was important enough in the Late Roman province of Syria Euphratensis Secunda to become a suffragan of its capital Sergiopolis's Metropolitan Archbishop, yet was to fade. The diocese was nominally restored in 1933 as a Latin Catholic titular bishopric Zenobia(s). The titular see was filled until 2010.

See also

- Cities of the ancient Near East

- Zalabiye

- Dura-Europos

- Resafa

References

- Astour, Michael C. (1992). "An Outline of the History of Ebla (Part 1)". In Gordon, Cyrus H. (ed.). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. pp. 3–82. ISBN 0-931464-77-3.

- Lauffray, J. (1983). Halabiyya-Zenobia. Place forte du limes oriental et la Haute-Mésopotamie au VIe siècle. I. Les duchés frontaliers de Mésopotamie et les fortifications de Zenobia. Bibliothèque Archéologique et Historique (in French). 119. Paris: P. Geuthner. OCLC 185419601.

- Butcher & Nicholson 2018.

- Burns, R. (2009). The monuments of Syria. A guide. London: I.B. Tauris. pp. 160–161. ISBN 978-1-84511-947-8.

- Bell, G.L. (1911). Amurath to Amurath. London: Heinemann. pp. 67–68. OCLC 2135999.

amurath to amurath.

- "Programme d'études archéologiques et de consolidations sur le site de Zénobia-Halabiyé" (in French). Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- "Zénobia Halabiyé, campagne 2009" (in French). Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- Government of the Syrian Arab Republic State Planning Commission & the United Nations Development Programme (2008). Reviving the business climate and boosting tourism in Deir Ezzor (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

Sources

- Butcher, Kevin; Nicholson, Oliver (2018). "Zenobia (mod. Halebiye, Syria)". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Note on the impact of the Halabiye Dam on Halabiye (in French)

- GCatholic with titular incumbent bio links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Halabiye. |