Zenkyoto

The All Campus Joint Struggle Committee (Japanese: 全学共闘会議; Zengakukyôtokaigi), commonly known as the Zenkyoto, was a basic Japanese student organization consisting of anti-Japanese Communist Party and non-sectarian radicals. Unlike other student movement organizations, graduate students and young teachers were allowed to participate. Active in the late 1960s, Zenkyoto was the driving force behind clashes between Japanese students and the police. Zenkyoto was not as political as it was a reaction to "American imperialism", Japanese "Monopoly Capitalism", and "Russian Stalinism".[1]:517 Much of the movement centered around nihilism and existentialism, which served as inspirations for revolution.

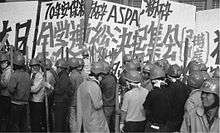

Since individual Zenkyoto groups were formed independently at each university, their timing, purpose, organization and policies were unique. Among Zenkyoto groups at universities, Nihon University and the University of Tokyo are the most well-known. The media reported that University of Tokyo Zenkyoto members tried to "dismantle colleges". In their protests, University of Tokyo Zenkyoto members threw stones and Gebaruto Bou staves at police. Some say that the University of Tokyo faction was more of a mass movement than an organized movement in which concrete ideas and policies were set forth. Zenkyoto policies could be more diverse depending on different universities and individuals.

Zenkyoto collaborated with the Democratic Youth League of Japan. They led a delegation of seven undergraduates to pressure University authorities to accept their demands during the period of conflict at the University of Tokyo. With the moving of the Ministry of Education after entrance examinations were cancelled, riot police were introduced to suppress a mass Zenkyoto protest. Athletic groups and people of different ethnicities participated in combat at Nihon University.

Origins

In 1948, the Zengakuren was founded with the ideas of a mass student union and a federal, self-managed organization. Initially very militant and engaged in student struggles, Zengakuren slowly became more moderate after time in their writings and actions. Zengakuren began to turn more and more to organizing picnics, fairs and more moderate activities. Zengakuren gradually became to become controlled by Japanese Communist Party executives.[2]

Through the 1960s, there were many student protests across Japanese universities. In September 1965, Ochanomizu University students organized a mass class abandonment in opposition to dormitory reform. At Takasaki City University of Economics in the same month, students protested against rising tuition fees. Other protests happened at Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology (November 1965), Waseda University (December 1965 - January 1966), Meiji University (November 1966), Chuo University (December 1966), and Keio University (1968).[3][4] It was with these student movements that Zenkyoto appeared in the 1960s, with each university developing movements independent of each other.

In disputes, particularly concerning tuition fees, university management corruption, and their use of violent guards (sometimes recruited from criminal organizations or far-right circles), students would gather in action committees (Kyôto Kaigi).[5]

Major conflicts

Nihon University

In May 1968, a demonstration was held in Nihon University, dubbed the 200 Meter Demonstration as a reaction to the secrecy of university authorities on the expenditure of 3400 million yen.[6]:107 On May 27, the Zenkyoto was formed by Akehiro Akita, who chaired the organization. The Zenkyoto consisted of anti-Communist and non-sectarian radicals. In response to student demands, University authorities held a conference at the Ryogoku Auditorium on September 30 to negotiate between students and authorities. The rally was attended by as many as 35,000 students. After 12 hours of negotiations, the authorities accepted the demands of the students, leading to the resignation of all University directors involved. However, following the negotiations, Japanese Prime Minister Eisaku Sato declared that "establishing relations with popular gangs deviate from common sense", and the authorities withdrew their promises to the students.[7] Students with associations to sports began to riot in Ryogoku Auditorium, and riot police was brought in. After the situation calmed down, Nihon University resumed classes in a temporary school complex in Shiraitodai, Fuchū, with 10 buildings surrounded by vacant fields and barbed wire. Staff were stationed at the entrance of the premises, and students were required to show student IDs. This complex was popularly called "Nihon Auschwitz", in reference to Auschwitz concentration camp.[8]

University of Tokyo

In January 1968, a dispute over the status of graduate students in the University of Tokyo Faculty of Medicine over the new Medical Doctors' Law which restricted employment opportunities and a judgement on a militant student made by the board led to mass protests in University of Tokyo. A Zenkyoto sprung up at the conflict in University of Tokyo, and Zenkyoto students occupied and fought in Yasuda Auditorium, which they had occupied in July, against riot police. In January 1969, 8500 riot police were called to Yasuda Auditorium to break up the protest.[9]:235–6[1]:517

Creation of the National Federation

With different action committees nationwide participating in solidarity with the Nihon Zenkyoto, the committees were federated into a nationwide Zenkyoto, escaping the supervision of the Zengakuren, who often sided with university authorities. Committees were organized by levels (students, staff, researchers, etc.) and by departments (humanities, medicine, literature, etc.). Each committee had a degree of autonomy. Committee members participated in committee debates, and decisions are voted on by a show of hands. Attempts by universities to arrest leaders of Zenkyoto were fruitless.[5] The National Federation of Zenkyoto was set up at Hibiya Park in September 1969. However, Yoshitaka Yamamoto, leader of the University of Tokyo Zenkyoto, who chaired the rally at Hibiya Park, was arrested.[1]:518

Spread

From 1968 to 1969, Zenkyoto expanded alongside conflicts in the University of Tokyo, "spreading like a wildfire" to universities nationwide.[4]:23

Zenkyoto initially only dealt with issues specific to each university (tuition fees, etc.) beyond the jurisdiction of university student councils. Later, after experiencing hard responses from university authorities as well as government intervention with riot police, Zenkyoto changed to deal with the change of the "philosophy of universities as a whole, as well as change of academic subjects and reviewing the way universities, students and researchers work." Zenkyoto believed that modern universities were "factories of education" embedded in imperialist forms of management, with faculty councils as "terminal institutions of power" responsible for their management. They claimed that "university autonomy" was no more than an illusion, and that dismantling such an administration would be an issue. They believed that universities should be dismantled by violence, such as university-wide blockades. According to Zenkyoto, the ideological question of "self-denial" should be advanced to deny statuses as students or researchers.[10]:151–2 Students began to use wooden staves against both the riot police and each other, with students taking their nihilism and anger not only onto university power structures, but themselves.[9]:237

The slogans of "disassembly of the university" and "self-denial" emerged in the student movement of University of Tokyo. The conflict at University of Tokyo transcended the boundaries of university issues and became a form of "conflict between students and state power".[10]:99 This was no longer a struggle that could be ended by a compromise at each university. Tomofusa Kure, a student involved in the conflict, said that "Self-negation is self-affirmation. To discover it is self-negation. Self-negation is not intended to be the aim - Rather, it emerges as a result of self-affirmation."[10]:162 This "self-negation" was a form of "negation of the university which produces men to serve capital as if in a factory, and also negation of the existence of students whose only future was to be cogs in the power machine thus created."[1]:518

Fall

Zenkyoto began to lose its momentum and the support of the students as university struggles were stuck in stalemates, with seemingly impossible demands, all the while universities were really in danger of being dissolved. Oda Makoto of the Bebeiren (Citizen's Alliance for Peace in Vietnam) group claimed that he would start his own movement if Zenkyoto could not destroy University of Tokyo.[1]:520 In August 1969, the Act on Temporary Measures concerning University Management was passed, coming into effect in late 1970, which allowed universities to call on riot police independently.

References

- Tsuzuki, Chushichi. “Anarchism in Japan.” Government and Opposition, vol. 5, no. 4, 1970, pp. 501–522. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/44484495.

- Toyomasa Fuse. Le radicalisme étudiant au Japon : une «révolution culturelle»?. L'Homme et la société, 1970, pp. 241-66

- Miyazaki, Shigeki. Flying Clouds. Private Edition, 2003.

- Yo Kozu. Top Secret Zenkyoto History - Chuo University, 1965-68. Irodoriryusha, 2007.

- ZENKIOTO: Student Struggle Committees of the 1960s and Anarchism in Japan. at https://lecridudodo.blogspot.fr, July 5, 2011

- Tsurumi, Kazuko. “Some Comments on the Japanese Student Movement in the Sixties.” Journal of Contemporary History, vol. 5, no. 1, 1970, pp. 104–112. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/259983.

- Asahi Shimbun, 2009.06.22. (Nippon Personal Network) Living in Rebellion: 2 I thought I won, Fengun. Interview with Akita Akehiro.

- Nihon Zenkyoto. Record of the Nihon Struggle A record of Nihon Zenkyoto.

- Kersten, Rikki. “The Intellectual Culture of Postwar Japan and the 1968-1969 University of Tokyo Struggles: Repositioning the Self in Postwar Thought.” Social Science Japan Journal, vol. 12, no. 2, 2009, pp. 227–245. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40649684.

- Manabu Miyazaki. Breakthrough. Nanpusha, 1996.