Yolanda of Vianden

Mother Yolanda (or Yolande, Iolanda) of Vianden, O.P., (1231–1283) was the youngest daughter of Count Henry I of Vianden and Margaret, Marchioness of Namur. She joined the Dominican monastery in Marienthal, Luxembourg, against the wishes of her parents when she was very young. She later became its devout prioress and is now a legend in the history of that nation.

The story of Yolanda

Yolanda's lasting fame is due in large part to the epic poem Yolanda von Vianden (see more below), written by Friar Hermann of Veldenz, O.P., which is one of only two works we have from him, the other being a prose account of her life. This poem recounts how, as a young girl, she wanted to become a nun against the wishes of her parents. Indeed, her mother had hoped to arrange a marriage to the noble Walram of Monschau, in order to consolidate the influence of the Counts of Vianden, especially in their relations with the Counts of Luxembourg. In 1245, when Yolanda was 14, her mother, the Marchioness Margaret of Courteney (French: Marguerite de Courtenay), brought Yolanda along as her companion on a visit to the Dominican monastery of Marienthal, where Yolanda unexpectedly fled into the protection of its cloister and gained admission as a novice.

A year later, her mother returned, now with the armed support of several noblemen, threatening to destroy the monastery unless Yolanda agreed to leave. The girl was thus persuaded to return to Vianden where her parents once again attempted to change her wishes by keeping her in Vianden Castle. But Yolanda did not waver. If anything, she was reinforced in her views through discussions with well-known Dominican friars such as Walter von Meisemburg and St. Albertus Magnus. Finally, even her mother relented and agreed that Yolanda should return to Marienthal. Entering a life of prayer and charity, Yolanda developed in her monastic life through the years, and was eventually elected the monastery's prioress in 1258. She remained there until her death 25 years later in 1283.[1] Her mother also joined the monastery after the death of her husband during a crusade (1252).

There is little remaining evidence of the life of Yolanda apart from a skull, said to be hers, which is displayed at the Church of the Trinitarians in Vianden. As the monastery was closed in the 18th century, there is no trace of her there today.

Yolanda's steadfast resolve to leave the riches and privileges of the nobility in favour of an austere and devout life in a monastery was as sensational as it was inspiring. This no doubt explains why Friar Hermann was inspired to write her life story, and why she has become such a revered figure, above all, for Luxembourgian women.[2]

The Yolanda poems

There are two poems which relate the life of Yolanda:

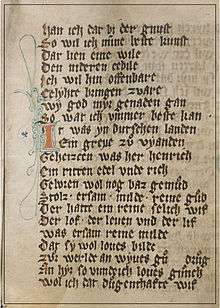

- Yolanda von Vianden by Friar Hermann of Veldenz[3] who wrote the story of her life in 1290 after her death in 1283. The work consists of 5,963 lines of rhyming couplets in Moselle Franconian with close similarities to today's Luxembourgish. Brother Hermann's epic appears to have lain in the Marienthal monastery for almost four centuries after he wrote it. In 1655 the then lost original was copied on paper by the Belgian Jesuit, Alexander von Wiltheim. At the same time, Wiltheim wrote a life of Yolanda in Latin based on Brother Hermann's Middle High German. Then in November 1999, the Luxembourg linguist Guy Berg discovered the original manuscript, now known as the Codex Mariendalensis, in Amsembourg Castle, a short distance from Marienthal. This was a very important discovery as it is considered to be the oldest manuscript in Luxembourgish.[3]

- A second poem about Yolanda, by an anonymous English author, has also recently come to light. Entitled Iölanda, A Tale of the Duchy of Luxembourg, it was published in 1832.[4] The author, who was told about Yolanda on a visit to the castle in Vianden, was apparently aware of Friar Hermann's account as he explains in his introduction that, for romantic reasons, he has changed the story so that it concludes with Iölanda's marriage.

References

- "Brother Hermann's 'Life of the Countess Yolanda of Vianden' [Leben der Graefen Iolande von Vianden] - Boydell and Brewer". boydellandbrewer.com. Retrieved 2018-06-12.

- Wiltheim, Alexander; Berg, Guy; Newton, Gerald (2007). The life of Yolanda of Vianden ; The life of Margaret of Luxembourg ; Genealogy of the Ancient Counts of Vianden: Antwerp, 1674 = Das Leben der Yolanda von Vianden ; Das Leben der Margarete von Luxemburg ; Genealogie der ehemaligen Grafen von Vianden : Antwerpen, 1674. Luxembourg: Institut Grand-Ducal, Section de Linguistique, d'Ethnologie et d'Onomastique. ISBN 9782919910243.

- Bruder Hermann: Yolanda von Vianden. Moselfränkischer Text aus dem späten 13. Jahrhundert, übersetzt und kommentiert von Gerald Newton und Franz Lösel (Beiträge zur Luxemburger Sprach- und Volkskunde XXI, Sonderreihe Language and Culture in Medieval Luxembourg 1). Luxembourg 1999. Romain Hilgert: Zwei Kilometer in 700 Jahren. Story of the rediscovery of the original manuscript of Yolanda von Vianden. Retrieved 15 January 2007.

- Iölanda, A Tale of the Duchy of Luxembourg, anonymous poem in English (1832). Archived June 10, 2007, at the Wayback Machine D'Land Luxembourg. Retrieved 15 January 2007