Yellow stingray

The yellow stingray (Urobatis jamaicensis) is a species of stingray in the family Urotrygonidae, found in the tropical western Atlantic Ocean from North Carolina to Trinidad. This bottom-dwelling species inhabits sandy, muddy, or seagrass bottoms in shallow inshore waters, commonly near coral reefs. Reaching no more than 36 cm (14 in) across, the yellow stingray has a round pectoral fin disc and a short tail with a well-developed caudal fin. It has a highly variable but distinctive dorsal color pattern consisting of either light-on-dark or dark-on-light reticulations forming spots and blotches, and can rapidly change the tonality of this coloration to improve its camouflage.

| Yellow stingray | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | U. jamaicensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Urobatis jamaicensis (Cuvier, 1816) | |

| |

| Range of the yellow stingray | |

| Synonyms | |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Urobatis jamaicensis. |

Relatively sedentary during the day, the yellow stingray feeds on small invertebrates and bony fishes. When hunting it may undulate its disc to uncover buried prey, or lift the front of its disc to form a "cave" attractive to shelter-seeking organisms. This species is aplacental viviparous, meaning that the developing embryos are sustained initially by yolk and later by histotroph ("uterine milk"). Females bear two litters of up to seven young per year in seagrass, following a gestation period of 5–6 months. Though innocuous towards humans, the yellow stingray can inflict a painful injury with its venomous tail spine. This species is taken as bycatch by commercial fisheries and collected for the aquarium trade; it may also be negatively affected by habitat degradation. Nevertheless, it remains common and widespread, which has led the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) to list it under Least Concern.

Taxonomy and phylogeny

French naturalist Georges Cuvier originally described the yellow stingray as Raia jamaicensis in 1816, in Le Règne Animal distribué d'après son organisation pour servir de base à l'histoire naturelle des animaux et d'introduction à l'anatomie comparée. He based his account on specimens obtained from Jamaica, though no type specimens were designated.[2] Subsequent authors moved this species to the genus Urolophus, and then to the genus Urobatis (some literature still refers to this species as Urolophus jamaicensis). Other common names used for this ray include the yellow-spotted ray, the round ray, and the maid ray.[3]

Nathan Lovejoy's 1996 phylogenetic analysis, based on morphology, found that the yellow stingray is the most basal member of a clade that also contains Pacific Urobatis species and the genus Urotrygon of Central and South America. This finding would render Urobatis polyphyletic, though further study is warranted to elucidate the relationships between these taxa.[4]

Description

The yellow stingray is small, growing no more than 36 cm (14 in) across and 70 cm (28 in) long.[1][5] It has a nearly circular pectoral fin disc slightly longer than wide, with a short, obtuse snout. The eyes are immediately followed by the spiracles. There is a narrow curtain of skin between the nostrils, with a fringed posterior margin.[6] The mouth is nearly straight and contains a transverse row of 3–5 papillae on the floor. There are 30–34 tooth rows in the upper jaw and a similar number in the lower jaw, arranged into bands. The teeth are broad-based, with low, blunt crowns in females and juveniles, and tall, pointed cusps in adult males. The teeth of males are more widely spaced than those of females. The pelvic fins have nearly straight leading margins and rounded trailing margins.[3][7]

The tail is stout and flattened, comprising less than half the total length, and terminates in a small, leaf-shaped caudal fin about a quarter high as long, that is continuous around the last vertebra.[6][7] A serrated spine is positioned about halfway along the tail.[8] Newborn rays are smooth-skinned; shortly after birth small, blunt tubercles appear in the middle of the back, which in larger adults extends to between the eyes, the "shoulders", and the base of the tail. Adults also develop recurved thorns along the upper margin of the caudal fin.[3] The color and pattern of the yellow stingray varies significantly among individuals, though most follow one of two schemes: minute dark green or brown reticulations on a light background, or dense white, yellow, or golden spots on a dark green or brown background. The underside is yellowish, greenish, or brownish white, with small darker spots toward the disc margin and the tail.[7] This species is capable of rapidly changing the tone and contrast of its coloration to better match its environment.[8]

Distribution and habitat

The yellow stingray is found throughout the inshore waters of the Gulf of Mexico (where it is the only representative of its family)[9] and the Caribbean Sea, including Florida, the Bahamas, and the Greater and Lesser Antilles to Trinidad. On rare occasions, it ranges as far north as Cape Lookout in North Carolina.[7][10] It is quite abundant in the Florida Keys and parts of the Antilles, and rather uncommon elsewhere. Off Mexico, this species occupies a salinity range of 26–40 ppt.[1]

Benthic in nature, the yellow stingray inhabits coastal habitats such as bays, lagoons, estuaries, and low-energy surf zones, and has been reported from the water's edge to a depth of 25 m (82 ft). It particularly favors insular hard-bottomed habitats with a dense encrustation of sessile invertebrates (termed live-bottom habitats), but can also be found over sand, mud or seagrass (Thalassia), sometimes in the vicinity of coral reefs.[1] Off Jamaica, large numbers of yellow stingrays, up to one per square meter, gather beneath the aerial roots of mangrove trees used as roosts by cattle egrets (Bubulcus ibis); it is theorized that the birds' droppings sustain invertebrates that attract the rays.[11] There is no evidence of seasonal migration, though during the spring females tend to be found closer to shore than males.[12]

Biology and ecology

During the day, the yellow stingray is fairly inactive and spends much time buried under a thin layer of sediment or lying motionless in vegetation.[13] Tracking studies have shown that it generally remains within a small home range of around 20,000 m2 (220,000 sq ft), with individuals covering only a portion of the entire area on any particular day. It favors the boundaries between different terrain, such as sand and reef.[12] Its periscopic eyes give it a 360° panoramic view of its surroundings; each eye bears an elaborate covering or "operculum" that allows fine control over the amount of light entering the pupil.[14] Therefore, the resting ray is well equipped to detect approaching predators, which may potentially include any large carnivorous fish such as the tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier).[3] The yellow stingray is most sensitive to sounds of 300–600 Hertz, which is fairly typical among sharks and rays that have been investigated thus far.[15] It and other stingrays have a large brain relative to other rays, comprising around 1–2% of the body weight.[16]

The diet of the yellow stingray is poorly documented but includes shrimps, and likely also worms, clams, and small bony fishes.[17][18] Typically, the ray will settle over a prey item and trap it against the bottom, whereupon it is manipulated to the mouth with motions of the disc.[19] Like the related round stingray (U. halleri), this species sometimes uses undulations of its disc margins to excavate pits and reveal buried prey.[3][9] It has also been observed raising the front of its disc to create a shaded "cave", to attract shelter-seeking organisms.[17] Known parasites of the yellow stingray include the tapeworms Acanthobothrium cartagenensis, Phyllobothrium kingae, Discobothrium caribbensis, Rhinebothrium magniphallum,[3] and R. biorchidum,[20] and the monogenean Dendromonocotyle octodiscus.[21]

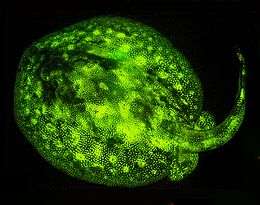

The yellow stingray exhibits biofluorescence, that is, when illuminated by blue or ultraviolet light, it re-emits it as green, and appears differently than under white light illumination. Biofluorescence potentially assists intraspecific communication and camouflage.[22]

Life history

Like other stingrays, the yellow stingray is aplacental viviparous: at first the embryos are sustained by yolk, which is later supplanted by histrotroph ("uterine milk", rich in proteins and lipids), delivered by the mother through numerous finger-like extensions of the uterine epithelium called "trophonemata".[23][24] Mature females have two functional uteruses, with the left used more than the right. Except in a few individuals, only the left ovary is functional. The reproductive cycle is biannual with a 5–6 month long gestation period. The first period of ovulation occurs from January to April, peaking in late February and early March, with birthing from June to September, peaking in late July and early August. The second period of ovulation occurs from August to September, with birthing from November to January. The two cycles overlap as vitellogenesis (yolk formation) begins while the female is still pregnant.[23]

Courtship and mating in the yellow stingray involves one or more males closely following a female, seeking to bite and grip the rear margin of her disc; the high, pointed teeth of males serve to aid in this endeavor. Once the male successfully holds onto the female, he flips under her so that the two are aligned abdomen-to-abdomen, and inserts a single clasper into her cloaca. Rival males may attempt to interfere with the mating pair by biting or bumping them. In one observation that took place in water 2.5 m (8.2 ft) deep near Tobacco Caye on the Belize Barrier Reef, the male pursuit lasted between 30 and 60 seconds and copulation lasted four minutes.[13][17]

The predominant source of embryonic nutrition is histotroph, which supports a 46-fold weight increase from ovum to near-term fetus.[23] By the time the embryo is 4.7 cm (1.9 in) across, it has fully resorbed its yolk sac and external gills.[25] The litter size ranges from one to seven. The first litter of the year (spring-summer) is larger than the second (autumn-winter), with the number of offspring increasing with the size of the female; this relationship is not observed for second litter. On the other hand, the newborns of the first litter tend to be slightly smaller than those of the second litter, at an average length of 14.5 cm (5.7 in) versus 15 cm (5.9 in). The second litter's fewer, larger young may reflect the lower temperatures of autumn-winter, which results in slower growth.[23] Seagrass beds serve as important habitat for parturition.[1] The newborns emerge tail-first and are similar in coloration to the adults, though the disc is relatively wider. They also have a small "knob" or "tentacle" that covers most of the spiracle, which is resorbed shortly after birth.[3][6] Males and females reach sexual maturity at disc widths of 15–16 cm (5.9–6.3 in) and 20 cm (7.9 in) respectively.[1] The maximum lifespan is 15–25 years.[26]

Human interactions

Generally, yellow stingrays pay little heed to divers and can be approached closely.[8] If stepped on or otherwise provoked, however, this ray will defend itself with its tail spine, coated in potent venom. The resulting wound is extremely painful, but seldom life-threatening.[3][9] Small and docile, the yellow stingray adapts readily to captivity and has reproduced in the aquarium; it requires a large amount of space (at least 180 gal or 684 L) and a fine, deep substrate with minimal ornamentation.[17]

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has listed the yellow stingray under Least Concern, citing its wide distribution and high abundance in certain regions. In addition, its small size implies relatively high productivity, which would make its population more resilient to fishing pressure. This species is not targeted commercially, but is probably taken incidentally by inshore fisheries throughout its range.[1] It is also harvested for the home aquarium trade, being the most frequently available member of its family on the North American market.[17] The extent of this trade has not yet been quantified. Another potential threat is habitat degradation, particularly to seagrass beds. No conservation measures have been enacted for this species.[1]

Gallery

A yellow stingray swimming over rubble.

A yellow stingray swimming over rubble. A yellow stingray resting on a reef in Miami, Florida.

A yellow stingray resting on a reef in Miami, Florida. A yellow stingray at the Oregon Coast Aquarium in Newport, Oregon.

A yellow stingray at the Oregon Coast Aquarium in Newport, Oregon. A yellow stingray swimming over a sandy substrate.

A yellow stingray swimming over a sandy substrate. A yellow stingray resting under a layer of sand in Cozumel, Mexico.

A yellow stingray resting under a layer of sand in Cozumel, Mexico..jpeg) A yellow stingray behind a gorgonian.

A yellow stingray behind a gorgonian.

References

- Piercy, A.N.; F.F. Snelson (Jr) & R.D. Grubbs (2006). "Urobatis jamaicensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2006: e.T60109A12302769. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2006.RLTS.T60109A12302769.en.

- Eschmeyer, W. N. (ed.) jamaicensis, Raia. Catalog of Fishes electronic version (19 February 2010). Retrieved on March 21, 2010.

- Piercy, A. Biological Profiles: Yellow Stingray. Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department. Retrieved on November 15, 2008.

- Lovejoy, N.R. (1996). "Systematics of myliobatoid elasmobranchs: with emphasis on the phylogeny and historical biogeography of neotropical freshwater stingrays (Potamotrygonidae: Rajiformes)" (PDF). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 117 (3): 207–257. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1996.tb02189.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-08. Retrieved 2010-03-22.

- Spieler, Richard E.; Fahy, Daniel P.; Sherman, Robin L.; Sulikowski, James A.; Quinn, T. Patrick (2013). "The Yellow Stingray, Urobatis jamaicensis (Chondrichthyes: Urotrygonidae): a synoptic review". Caribbean Journal of Science. 47 (1): 67–97. doi:10.18475/cjos.v47i1.a8. ISSN 0008-6452.

- McEachran, J.D. & M.R. de Carvalho (2002). "Dasyatidae". In Carpenter, K.E. (ed.). The Living Marine Resources of the Western Central Atlantic (Volume 1). Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. pp. 562–571. ISBN 92-5-104825-8.

- McEachran, J.D. & J.D. Fechhelm (1998). Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico: Myxiniformes to Gasterosteiformes. University of Texas Press. p. 184. ISBN 0-292-75206-7.

- Ferrari, A. & A. Ferrari (2002). Sharks. Firefly Books. p. 227. ISBN 1-55209-629-7.

- Parsons, G.R. (2006). Sharks, Skates, and Rays of the Gulf of Mexico: A Field Guide. University Press of Mississippi. p. 132. ISBN 1-57806-827-4.

- McClane, A. J. (1978). McClane's Field Guide to Saltwater Fishes of North America. Macmillan. p. 45. ISBN 0-8050-0733-4.

- Sumich, J.L. & J.F. Morrissey (2004). Introduction to the Biology of Marine Life (eighth ed.). Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 103. ISBN 0-7637-3313-X.

- Fahy, D.P. and R.E. Spieler. Activity patterns, distribution and population structure of the yellow stingray, Urobatis jamaicensis in Southeast Florida (abstract). American Elasmobranch Society 2005 Annual Meeting, Tampa, Florida.

- Young, R.F. (1993). "Observation of the mating behavior of the yellow stingray, Urolophus jamaicensis". Copeia. 1993 (3): 879–880. doi:10.2307/1447257. JSTOR 1447257.

- McComb, D.M. & S.M. Kajiura (2008). "Visual fields of four batoid fishes: a comparative study". Journal of Experimental Biology. 211 (4): 482–490. doi:10.1242/jeb.014506. PMID 18245624.

- Casper, B.M. & D.A. Mann (May 2006). "Evoked potential audiograms of the nurse shark (Ginglymostoma cirratum) and the yellow stingray (Urobatis jamaicensis)". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 76 (1): 101–108. doi:10.1007/s10641-006-9012-9.

- Walker, B.K. & R.L. Sherman (2001). "Gross brain morphology in the yellow stingray, Urobatis jamaicensis" (PDF). Florida Scientist. 64 (4): 246–249. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-09. Retrieved 2010-03-25.

- Michael, S.W. (2001). Aquarium Sharks & Rays. T.F.H. Publications. pp. 151–152, 235. ISBN 1-890087-57-2.

- O'Shea, O. R.; Wueringer, B. E.; Winchester, M. M.; Brooks, E. J. (2018). "Comparative feeding ecology of the yellow ray Urobatis jamaicensis (Urotrygonidae) from The Bahamas". Journal of Fish Biology. 92 (1): 73–84. doi:10.1111/jfb.13488. ISSN 1095-8649. PMID 29105768.

- Mulvany, S.L. & P.J. Motta (2009). "Feeding kinematics of the Atlantic stingray (Dasyatis sabina) and yellow stingray (Urobatis jamaicensis)". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 49: E279. doi:10.1093/icb/icp003.

- Huber, P.M. & G.D. Schmidt (1985). "Rhinebothrium biorchidum n. sp., a tetraphyllidean cestode from a yellow-spotted stingray, Urolophus jamaicensis, in Jamaica". Journal of Parasitology. 71 (1): 1–3. doi:10.2307/3281968. JSTOR 3281968. PMID 3981333.

- Pulido-Flores, G. & S. Monks (January 2005). "Monogenean parasites of some Elasmobranchs (Chondrichthyes) from the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico". Comparative Parasitology. 72 (1): 69–74. doi:10.1654/4049.

- Sparks, John S.; Schelly, Robert C.; Smith, W. Leo; Davis, Matthew P.; Tchernov, Dan; Pieribone, Vincent A.; Gruber, David F. (2014). "The Covert World of Fish Biofluorescence: A Phylogenetically Widespread and Phenotypically Variable Phenomenon". PLOS One. 9 (1): e83259. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0083259. PMC 3885428. PMID 24421880.

- Fahy, D.P.; R.E. Spieler & W.C. Hamlett (2007). "Preliminary observations of the reproductive cycle and uterine fecundity of the yellow stingray, Urobatis jamaicensis (Elasmobranchii: Myliobatiformes: Urolophidae) in Southeast Florida, U.S.A." (PDF). The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology. Supplement 14: 131–139.

- Hamlett, W.C. & M. Hysell (1998). "Uterine specializations in elasmobranchs". Journal of Experimental Zoology. 282 (4–5): 438–459. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-010X(199811/12)282:4/5<438::AID-JEZ4>3.3.CO;2-Y. Archived from the original on 2013-01-05.

- Basten, B.L.; R.L. Sherman; A. Lametschwandtner & R.E. Spieler (2009). "Development of embryonic gill vasculature in the yellow stingray, Urobatis jamaicensis". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A. 153A (2): S69. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.04.021.

- Animals: Yellow Stingray Archived 2014-10-28 at the Wayback Machine. Pittsburgh Zoo & PPG Aquarium. Retrieved on March 25, 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Urobatis jamaicensis. |