Wugongchuan

The wugongchuan (蜈蚣船), or centipede ship, is a Chinese oared vessel of the 16th century inspired by the Portuguese galley. The defining characteristic of the wugongchuan is its numerous oars on its sides, evoking the image of a centipede, giving it its name. The wugongchuan was part of a series of Chinese experimentation with European ship designs of the period, as they attempted to fit onto their ships the new breech-loading swivel guns, also brought by the Portuguese. Until this time, oars in such numbers were rarely used in large Chinese crafts.[1]

Characteristics

The wugongchuan were built based on what the Chinese observed from Portuguese ships. The mid-Ming dynasty text Longjiang chuanchang zhi (龍江船廠志, Account of the Longjiang Shipyard) describes their observations as follows: "The Portuguese ships had a length of ten zhang and a width of three zhang (approximately 36 × 11 meters). They had forty oars on each side, carried three to four guns, had a sharp-pointed keel and a flat deck and were thus safe against storms and high waves. Moreover, the crew was protected by breastwork and therefore had no need to fear arrows and stones. There were two hundred men altogether, with many pulling the oars, which made these ships very fast, even if there was no wind. When the guns were fired and the gun balls poured like rain, no enemy could resist. These ships were called wugongchuan."[2]

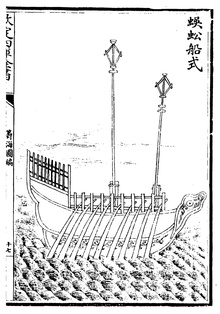

The same text also carries an alternate description of the wugongchuan along with an illustration. In this description, the wugongchuan's dimension is given as eight zhang by one zhang and six chi, and the illustration shows a flat keel in traditional Chinese style, two masts, and nine oars on each side of the ship.[2] This description is associated with a smaller version of the Portuguese galley that the Chinese constructed in Nanjing, their own wugongchuan.[3] The drastically reduced number of oars may be explained by substituting some of the oars with Chinese yulohs, or sculling oars at the stern of the ship.[4][5] The keel being flat may indicate difficulties encountered by the Chinese to adjust to European designs, despite the text noting that the prow and stern of a wugongchuan differed from other Chinese ships.[6]

History

The Portuguese explorers reached Chinese shores in 1513 and started trading at the port of Tamão in the Pearl River Delta, Guangdong province. Around this time, European firearms, artillery, and ship designs were introduced to China among other European goods and ideas. Some time during the following decade, a Chinese Christian whose name was recorded by the Portuguese as Pedro went to the local authorities in Guangzhou and told them of Portuguese exploits in Malacca and Cochin, and convinced them to let him build two galleys in the Portuguese fashion. The authorities found the finished galleys to be lop-sided and considered them a waste of wood, and ordered that no more be made.[7]

It wasn't until hostilities broke out between the Chinese and the Portuguese that the Chinese saw value in Portuguese ships. The Guangdong surveillance commissioner Wang Hong (汪鋐) enticed two Chinese artisans who worked with the Portuguese by the names of Yang San (楊三) and Dai Ming (戴明) to pass on their knowledge to their compatriots. Using the new guns, cannons, and ships, Wang Hong was able to drive the Portuguese out of Tamão in the Battle of Xicaowan in 1523.[3] After that, Wang Hong recommended to the imperial court to build cannons for defensive purposes, and the recommendation was accepted. Since it was argued that cannons cannot be mounted on any ship other than the wugongchuan, the shipyards in Nanjing sent for artisans from Guangdong to build the wugongchuan.[8] The finished wugongchuan were praised for its speed and effectiveness with cannons.[3]

In 1534, after years of experimentation with the wugongchuan, it was argued that similar Chinese ships function as well as the wugongchuan when fitted with oars and minor technical changes. Therefore, it was decided that the imperial court should not "copy the models of inferior barbarians" (小夷) and stop using the exotic name associated with these ships.[3] It appears no more wugongchuan were produced after 1534.[9]

References

Notes

- Needham, Wang & Lu 1971, p. 625.

- Ptak 2003, p. 74.

- Ptak 2003, p. 75.

- Ptak 2003, p. 78.

- Needham, Wang & Lu 1971, p. 626 note e.

- Ptak 2003, p. 79.

- Ptak 2003, p. 77.

- Ptak 2003, p. 76.

- Ptak 2003, p. 80.

Works cited

- Needham, Joseph; Wang, Ling; Lu, Gwei-djen (1971). Science and Civilisation in China. Volume 4. Physics and Physical Technology. Part 3. Civil Engineering and Nautics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521070607.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ptak, Roderich (2003). "The Wugongchuan (Centipede Ships) and the Portuguese". Revista de cultura. 5: 73–83.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)