Worked-example effect

The worked-example effect is a learning effect predicted by cognitive load theory (Sweller, 1988). Specifically, it refers to the learning effect observed when worked-examples are used as part of instruction, compared to other instructional techniques such as problem-solving (Renkl, 2005) and discovery learning (Mayer, 2004). According to Sweller: "The worked example effect is the best known and most widely studied of the cognitive load effects" (Sweller, 2006, p. 165).

Worked-examples improve learning by reducing cognitive load during skill acquisition, and "is one of the earliest and probably the best known cognitive load reducing technique" (Paas et al., 2003). In particular, worked-examples provide instructions to reduce intrinsic cognitive load for the learner initially when few schemas are available. Extraneous load is reduced by scaffolding of worked-examples at the beginning of skill acquisition. Finally, worked-examples can increase germane load when prompts for self-explanations are used (Paas et al., 2003).

Renkl (2005) suggests that worked-examples are best used in "sequences of faded examples for certain problem types in order to foster understanding in skill acquisition," and that prompts, help system, and/or training be used to facilitate the learners' self-explanations. This view is supported by experimental findings comparing a faded worked-example procedure and a well-supported problem solving approach (Schwonke et al., 2009).

"However, it is important to note that studying [worked-examples] loses its effectiveness with increasing expertise" (Renkl, 2005), an effect known as the expertise reversal effect (Kalyuga, 2007). Further limitations of the classical worked-example method include "focusing on one single correct solution and on algorithmic skill domains" (Renkl, 2005). Addressing such restrictions in multimedia learning environments remains an area of active research (Renkl, 2005).

Definitions

Worked example

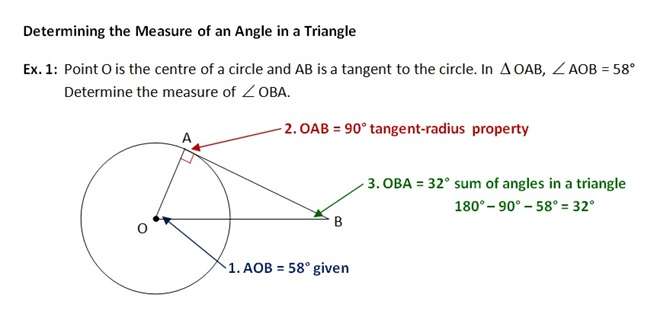

"A worked example is a step-by-step demonstration of how to perform a task or how to solve a problem" (Clark, Nguyen, Sweller, 2006, p. 190). Worked-examples are designed to support initial acquisition of cognitive skills through introducing a formulated problem, solution steps and the final solution (Renkl, 2005). Studying worked-examples is an effective instructional strategy to teach complex problem-solving skills (van Merriënboer, 1997). This is because example-based instruction provides expert mental models, to explain the steps of a solution for novices.

Worked examples, like the example above, are commonly found in mathematics or geometry textbooks, but they are also used in other fields. Worked-examples had been developed for music, chess, athletics, and computer programming (Atkinson, Derry, Renkl, & Wortham, 2000).

Faded worked examples

"In order to facilitate the transition from learning from worked examples in earlier stages of skill acquisition to problem solving in later stages, it is effective to successively fade out worked solution steps" (Renkl et al., 2004). Fading out steps in worked-example triggers self-explanation activities, which consists of the learners' own explanations to the reasons for the given solution steps (Renkl et al., 2004).

As learners gain expertise in the subject area of interest, worked-examples lose their effectiveness due to the expertise reversal effect. Using faded worked-examples addresses this effect by structuring the learners' transition from studying worked-example to learning with problem-solving. (Salden et al., 2008)

Self-explanations

According to Renkl (2005), self-explanations are "explanations provided by learners and mainly directed to themselves. They contain information that is not directly given in the learning materials and that refer to solution steps and the reasons for them. They can also refer to structural and surface features of problems or problem types."

"Self-explanations are important and necessary" (Chi et al., 1989) when working with worked-example as "successful learners studied the examples for longer periods and explained them more actively to themselves" (Chi et al., 1989). However, as most learners are passive and superficial self-explainers (Renkl, 1997), they "should be guided to actively self-explain worked-out examples" (Renkl, 2005).

Evidence for

The worked-example effect suggests that learning by studying worked examples is more effective than problem solving, and a number of research studies have demonstrated this effect.

Sweller and Cooper were not the first to use this form of instruction, but certainly they were the first to describe it from a cognitive load perspective (Sweller & Cooper, 1985; Cooper & Sweller, 1987; Sweller, 1988). While studying problem-solving tactics, Sweller and Cooper used worked examples as a substitute for conventional problem-solving for those learning algebra. They found that learners who studied worked examples, performed significantly better than learners who actively solved problems (Sweller & Cooper, 1985; Cooper & Sweller, 1987). Sweller and Cooper (1985) had developed worked examples as a means of limiting problem solving search. It is important to note, that Sweller & Cooper (1985) used worked-out example-problem pairs as opposed to individual worked examples. Renkl (2005) suggests learning from worked-out examples is more effective when a series is used. Pillay (1994) found that worked examples showing 3 intermediate problem stages were more effective than showing only one but suggested that the distance between stages needs to be small enough to allow students to connect them without having to create their own linkages.

Schwonke et al. (2009), in two experiments with Cognitive Tutors investigated the worked example effect. In one experiment, students used Geometry Cognitive Tutor which differed by the presentation of worked examples or not. In the experiment, students that were presented with worked examples needed less learning time to obtain the procedural skill and conceptual understanding of Geometry. In the second experiment, the authors aimed at avoiding the negative effects that occurred due to the lack of understanding of the purpose of worked examples, replicate the positive effects obtained in the first experiment and investigate the underlying learning approaches that explain why worked examples had greater efficiency effects. To achieve these objectives, the students were asked to think aloud, using the think aloud protocol. The results showed that the efficiency effect obtained in the first experiment was also replicated in the second experiment and the students had a deeper conceptual understanding (Schwonke et al., 2009).

Gog, Kester and Paas (2011) investigated the effectiveness of three strategies of example-based learning to problem solving on novices' cognitive load and learning; using electrical circuits troubleshooting tasks. The three strategies used are: worked example only, example-problem pairs and problem-example pairs. The results of the study showed that students in the worked example only and example-problems pair's conditions significantly outperformed students in the problem-example pair and problems solving conditions. It was also observed that higher performance was reached with significantly lower investment of mental efforts during the training (Gog, Kester and Paas, 2011).

Expertise reversal effect

Although a number of research studies have shown that worked-examples have positive effects on learners, Kalyuga et al. (2000, 2001a, b) showed that the worked-example effect is related to the expertise level of a learner, referred to as expertise reversal effect. In three studies, (Kalyuga et al. 2000, 2001a, b) used worked examples in different experiments, on-screen diagrams in mechanical engineering, examples with explanatory based instruction on writing circuits for relay circuits and programming logic. In the different studies, (Kalyuga et al. 2000, 2001a, b) showed that the efficiency effect of worked examples became ineffective and often resulted in negative effects for more knowledgeable learners (Kalyuga, 2007). However, Nievelstein et al. (2013) argues that both the worked-example effect and the expertise reversal effect that have been previously studied were based on well-structured cognitive tasks such as mechanics (Kalyuga et al. 2000). In a study using less-structured task, using legal cases, Nievelstein et al. (2013) investigates worked example effect and expertise reversal effects on both novice and advanced law students. The results of the study indicate that worked examples had efficiency effect for both the novice students and advanced law students, even though the advanced students had significantly more prior knowledge.

Another issue regarding worked examples was observed by Quilici & Mayer (1996), who found that providing learners with three examples of each problem type, as opposed to one, did not result in any differences in students' ability to sort subsequent problems into the appropriate types. As Wise & O'Neill, pointed out, this is not to say additional guidance will never lead to learning gains; we just cannot assume it always will.

There is also some debate as to how complete the worked example needs to be. Paas (1992) found that learners in a "completion" condition, who were given a problem only halfway worked out, performed just as well on test problems as those given the problems fully worked.

Developing effective worked examples

Ward and Sweller (1990) suggested that under some conditions "worked examples are no more effective, and possibly less effective, than solving problems" (p. 1). Thus it is important that worked examples be structured effectively, so that extraneous cognitive load does not impact learners. Chandler and Sweller (1992) suggested an important way to structure worked examples. They found that the integration of text and diagrams (within worked examples) reduces extraneous cognitive load. They referred to this single modality, attention learning effect as the split-attention effect (Chandler and Sweller, 1992). Tabbers, Martens, & Van Merriënboer (2000) proposed that one may prevent split-attention by presenting text as audio.

Renkl (2005) suggests that students only gain deep understanding through worked-out examples when the examples: (1) are self-explanatory, (2) provide principle-based, minimalist, and example-relation instructional explanations as help (3) show relations between different representations (4) highlight structural features that are relevant for selecting the correct solution procedure (5) isolate meaningful building blocks.

Not all worked examples are print-based as those in the Tarmizi and Sweller study. Lewis (2005) for instance, proposed animated demonstrations are a form of worked example. Animated demonstrations are useful because this multimedia presentation combines the worked example, and modality effects within a single instructional strategy.

Audience

Novice learners

As it turns out, worked examples are not appropriate for all learners. Learners with prior knowledge of the subject find this form of instruction redundant, and may suffer the consequences of this redundancy. This has been described as the expertise reversal effect (Kalyuga, Ayres, Chandler, & Sweller, 2003). It is suggested that worked examples be faded over time to be replaced with problems for practice (Renkl, Atkinson & Maier, 2000). Thus it is important to consider the learner as well as the media while developing worked examples, else learners may not perform as expected.

Since worked-out examples include the steps toward reaching the solution; they can only be used in skill domains where algorithms can be applied (mathematics, physics, programming, etc.)(Renkl, 2005). For creative pursuits such as interpreting poems, or learning contexts when there is an infinite number of potential confounding factors such as conflict resolution, effective leadership, or multicultural communication, solution steps are more difficult to describe and worked-out examples may not be the most effective instructional method. Worked-out example approach is considered one of the best multimedia principles of learning mathematics. Worked examples helps to direct the learner's attention to what needs to be studied as well as developing literacy skills. It serves as a guide to preparing novice learners for effective problem solving after gaining an understanding of any concept under consideration. Renkl (2005) argues that learners have a very restricted understanding of the domain when they try to solve problems without any worked examples. Thus, learners gain deep understanding of a skill domain when they receive worked-out examples in the beginning of cognitive skill acquisition. The examples give learners a clue on the right steps to solving the problem.

A recent research (Rourke, 2006) found that novice learners can still have difficulty understanding concepts if the given examples with incomplete or somewhat inaccurate information (known as faded examples) prior to acquiring basic domain knowledge or literacy skills in the subject matter. This is based on how novice and expert learner structure his or her learning schemas - knowing the appropriate procedure/approach to use in retrieving and interpreting the problem. On the other hand, worked out examples may constitute cognitive load and causing redundancy to learners with prior knowledge (Kalyuga, Ayres, Chandler, & Sweller, 2003), in contrast with novice learners in which worked out examples rather serve as a compass that provides direct guides to solving similar problems (Rourke, 2006). This also apply when novice learners evaluate prototypes, which embody the main characteristics of a work, worked examples. This can also assist the novice learner with the semantic processing needed to fully comprehend a work of art or design (Rourke, 2006).

Worked examples model is one of several strong cognitive-instruction techniques with great importance that help teachers foster learning. It is an application principle that significantly enhances novice learners' patterns of knowledge acquisition in the contexts of authentic problem solving. Reed & Bolstad (1991) indicate that one example may be insufficient for helping a student induce a usable idea and that the incorporation of a second example illustrating the idea, especially one that is more complex than the first, garners significant benefits for transfer performance. So, "at least add a second example" appears to be a basic rule for worked-examples instructional design. In addition, Spiro, Feltovich, Jacobson, & Coulson (1991) affirmed that providing a wide range of examples (and having students emulate examples) that illustrate multiple strategies and approaches to similar problems help foster broad knowledge transfer and "cognitive flexibility".

The instructional model of example-based learning by Renkl and Atkinson (2007) suggests that students gain a deeper understanding of domain principles when they receive worked examples at the beginning of cognitive skill acquisition.

See also

References

- Atkinson, R.K., Derry, S.J., Renkl, A., & Wortham, D.W. (2000). Learning from examples: Instructional principles from the worked examples research. Review of Educational Research, 70, 181–214.

- Chi, M. T., Bassok, M., Lewis, M. W., Reimann, P., & Glaser, R. (1989). Self-explanations: How students study and use examples in learning to solve problems. Cognitive science, 13(2), 145-182.

- Clark, R.C., Nguyen, F., and Sweller, J. (2006). Efficiency in learning: evidence-based guidelines to manage cognitive load. San Francisco: Pfeiffer.

- Cooper, G., & Sweller, J. (1987). Effects of schema acquisition and rule automation on mathematical problem-solving transfer. Journal of Educational Psychology. 79(4), 347–362.

- Gog, T.V., Kester, L., Paas, F. (2011). Effects of worked examples, example-problem, and problem-example pairs on novices' learning. Contemporary Educational Psychology 36 (2011) 212–218.

- Kalyuga, S., Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. (2000). Incorporating learner experience into the design of multimedia instruction. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92, 126–136.

- Kalyuga, S., Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. (2001a). Learner experience and efficiency of instructional guidance. Educational Psychology, 21, 5–23.

- Kalyuga, S., Chandler, P., Tuovinen, J., & Sweller, J. (2001b). When problem solving is superior to studying worked examples. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93, 579–588.

- Kalyuga, S. Ayres, P., Chandler, P. & Sweller, J. (2003). The expertise reversal effect. Educational Psychologist, 38(1) 23–31.

- Kalyuga, S. (2007). Expertise Reversal effect and its implications for learner-tailored instruction. Educational Psychology Review (2007) 19:509-539.

- Lewis, D. (2005). Demobank: a method of presenting just-in-time online learning in the Proceedings of the Association for Educational Communications and Technology (AECT) Annual International Convention (vol 2, pp. 371–375) October 2005, Orlando, FL. http://www.davidlewisphd.com/publications/dlewis_aect2005paper.pdf

- Moreno, R., Reisslein, M., and Delgoda G.E. (2006). Toward a fundamental understanding of worked example instruction: impact of means-ends practice, backward/forward fading, and adaptivity. In FIE '06: Proceedings of the 36th Frontiers in Education Conference, 2006. retrieved November 28, 2007 from http://fie.engrng.pitt.edu/fie2006/papers/1353.pdf

- Nievelstein, F., Gog T.V., Dijck, G.V., Boshuizen, H.P.A. (2013). The worked example and expertise reversal effect in less structured tasks: Learning to reason about legal cases. Contemporary Educational Psychology 38 (2013) 118–125.

- Paas, F. (1992). Training strategies for attaining transfer of problem-solving skill in statistics: A cognitive-load approach. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84, 429-434.

- Paas, F. & van Merriënboer, J. (1994). Variability of worked examples and transfer of geometrical problem-solving skills: A cognitive-load approach. Journal of Educational Psychology, 86 (1), 122-133.

- Paas, F., Renkl, A., & Sweller, J. (2003). Cognitive load theory and instructional design: Recent developments. Educational psychologist, 38(1), 1-4.

- Pillay, H. (1994). Cognitive load and mental rotation: Structuring orthographic projection for learning and problem solving. Instructional Science, 22, 91-113.

- Quilici, J.L., & Mayer, R.E. (1996). Role of examples in how students learn to categorize statistics word problems. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88, 144-161.

- Reed, S. K., & Bolstad, C. A. (1991). Use of examples and procedures in problem solving. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 17, 753-766.

- Renkl, A. (2005). The worked-out examples principle in multimedia learning. In Mayer, R.E. (Ed.), The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. View in a new window

- Renkl, A. (1997). Learning from worked-out examples: A study on individual differences. Cognitive science, 21(1), 1-29.

- Renkl, A., Atkinson, R. K., & Große, C. S. (2004). How fading worked solution steps works–a cognitive load perspective. Instructional Science, 32(1-2), 59-82.

- Renkl, A., Atkinson, R.K., & Maier, U.H. (2000). From studying examples to solving problems: Fading worked-out solution steps helps learning. In L. Gleitman & A.K. Joshi (Eds.), Proceedings of the 22nd Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society (pp. 393–398). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. retrieved February 6, 2010 from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.23.6816

- Rourke, A, J. (2006). Cognitive load theory and the use of worked examples in design history to teach novice learners to recognise the distinctive characteristics of a designer's work. EdD, Kensington: The University of New South Wales.

- Salden, R.J.C.M, Aleven, V., Schwonke, R., & Renkl, A. (2008). The expertise reversal effect and worked examples in tutored problem solving. Instructional Science, 38, 289-307

- Schwonke, R., Renkl, A., Krieg C., Wittwer, J., Alven, V., and Salden, R,. (2009). The worked-example effect: Not an artefact of lousy control conditions. Computers in Himan Behavior 25(2009)258-266.

- Smith, S.M., Ward, T.B., and Schumacher, I.S. (1993). Constraining effects of examples in a creative generation task, Memory & Cognition. 21: 837–845.

- Spiro, R. J., Feltovich, P. J., Jacobson, M., & Coulson, R. L. (1991). Cognitive flexibility, constructivism and hypertext: Advanced knowledge acquisition in ill-structured domains. Educational Technology, 31, 24-33.

- Sweller, J., & Cooper, G.A. (1985). The use of worked examples as a substitute for problem solving in learning algebra. Cognition and Instruction, 2(1), 59–89.

- Sweller, J. (2006). The worked example effect and human cognition. Learning and Instruction, 16(2) 165–169

- Tabbers, H.K., Martens, R.L., & Van Merriënboer, J.J.G. (2000). Multimedia instructions and cognitive load theory: Split-attention and modality effects. Paper presented at the National Convention of the Association for Educational Communications and Technology, Long Beach, CA. retrieved December 6, 2007 from

- Tarmizi, R.A. and Sweller, J. (1988). Guidance during mathematical problem solving. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80 (4) 424–436

- Van Merriënboer, J. (1997). Training Complex Cognitive Skills: a Four-Component Instructional Design Model for Technical Training. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications.

- Ward, M. & Sweller, J. (1990). Structuring effective worked examples. Cognition and Instruction, 1990, 7(1), 1–39. Sweller & Chandler, 1991

- Wise, A. F., & O'Neill, D. K. (2009). Beyond More Versus Less: A Reframing of the Debate on Instructional Guidance. In S. Tobias & T. M. Duffy (Eds.), Constructivist Instruction: Success or Failure? (pp. 82–105). New York: Routledge. View in a new window