Wilson Carlile

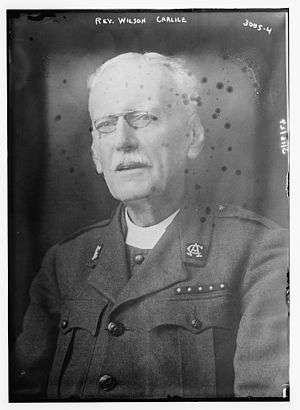

Wilson Carlile, CH (1847–1942) was an English priest and evangelist who founded the Church Army and was a prebendary of St Paul's Cathedral, London. Known as "The Chief", Carlile inspired generations of evangelists.

Early years

Carlile was born in 1847, the eldest of a middle-class family of 12 (one of whom was Sir Hildred Carlile) in Brixton, England. As a child, music was a great delight to him. Before he was three, his mother found him on tiptoe trying to play the family piano. He figured out some pleasing chords and persuaded his mother to help him learn more. From then on much of his time was spent on music. He was also good at languages. When he was sent to school in France at age 14, he quickly learned to speak French. In later life, he was also proficient in German and Italian.

Upon his return from France he joined his grandfather's business firm and by age eighteen, owing to his grandfather's failing health, Carlile came to be mostly in control. Thus, at the beginning of the 1870s he found himself a successful young businessman. He was ambitious, having determined he would earn his first 20,000 pounds before he turned twenty-five. By the time of that birthday (1872), he had made well over that amount.[1]

From depression to rebirth

In 1873, a great depression began and continued with a few breaks until 1896. It brought poverty and distress to working people, but also had immediate and disastrous effects upon the business community. Carlile was among those severely affected by the depression. The prosperity which he had carefully built up suddenly failed. Mental strain led to a physical breakdown and for many weeks he was confined to his bed. All this time he had spent in acquiring material wealth and position, and all for nothing. He began to question the purpose of life. No answer given to him brought him any satisfaction until he happened to read Mackay's Grace and Truth. Later he would say:

I have seen the crucified and risen Lord as truly as if He had made Himself visible to my bodily sight. That is for me the conclusive evidence of His existence. He touched my heart, and old desires and hopes left it. In their place came the new thought that I might serve Him and His poor and suffering brethren.

Although upon his physical recovery his father took him into his own firm, Carlile’s real interest now lay in religious work. He first joined the Plymouth Brethren who met at Blackfriars in London and worked among young hooligans in that area.[2] Soon he was confirmed in the Church of England, his father having joined some time before. About this time, in 1875, Dwight L. Moody held his great rallies in Islington. Wilson offered his help. Ira Sankey, the musical director, recognised the young man's ability and placed him at the harmonium where he accompanied the singing of the huge crowds who came to hear Moody. Following this mission he went with Moody to Camberwell where he chose and trained the choir for the South London mission. Thus he gained a solid understanding of the techniques of evangelism and the part that music can play. This knowledge would stand him in good stead when he became leader of the Church Army.

Theological education and early ministry

He learned more from Dwight Moody than this. He learned the essentials of his new-found faith and became inspired with the ambition of becoming an evangelist. In time he joined the Church of England and then decided to take holy orders. He was accepted by the London School of Divinity and after 18 months passed his examinations, having been ordained a deacon at St Paul's Cathedral in Lent 1880. Following this, he was accepted as a curate at St Mary Abbots, Kensington. Through his curacy, he wanted to reach people, including the guard at Kensington Palace, who had nothing to do with the church. Ordinary working people regarded the churches as "resorts of the well-to-do" (Charles Booth) and believed they would find no welcome within. Wilson wanted this to change and was determined to break down all barriers.

Since none of his efforts to bring ordinary people into his congregation worked, he decided to hold open-air meetings to attract folk as they passed by. As time went on, he drew others to help him and people began gathering in such large numbers that the police told them to 'move on.' There were complaints and Carlile was told that his meetings would have to stop, but he was also encouraged to continue them elsewhere in a more appropriate spot.

Church Army

Carlile resigned his curacy to devote his time to slum missions. His goal was to use the working person to help fellow workers, but to do so within the structure of the Church of England. Such work had already begun in a few other areas of England. Carlile wanted to co-ordinate all their efforts, so that trained evangelists could be sent to any parish where they were needed.

During this time, he visited the Salvation Army, where he received a "Soldier's Pass" which admitted him to private gatherings. He showed this on a train to his friend, F. S. Webster, the future rector of All Souls Church, Langham Place. Webster recalls, "I remember Mr Carlile explained that it was an Army and not a Church, that people could be banded together for purposes of evangelisation and soul-winning." Carlile began a "Church Salvation Army" in Kensington while Webster began one in Oxford. Bramwell Booth remembered Webster as "more than once walking in our processions, singing the praises of God though plastered with mud from head to foot."[3]

It took time for the idea to catch hold, but in 1882 the Church Army was born. Why 'Army?' Carlile's answer was that the evangelists intended to make war against sin and the devil. Also it was a time of wars – the Franco-German war and the First Boer War were not long over. It was a time of Army consciousness and discipline from above.

As long as Carlile was the head of Church Army, he remained authoritative and masterful, but always he recognised the higher authority of the Church of England. No work was carried out in any parish without the approval of the incumbent, nor in any prison or public institution unless the evangelists were invited by the chaplain.

Carlile met resistance in the early years but he persisted in trying to acquaint clerics and public officials in major cities with Church Army's aims, ideas and methods. In 1885, the Upper House of the Convocation of Canterbury passed a resolution of approval. With increasing support from a few bishops, the Army gradually gained the respect of the church. By 1925, the Church Army grew to become the largest home mission society in the Church of England.

He ministered at St Mary-at-Hill in the City of London, in the late 19th/early 20th century[4] Carlile was appointed a Companion of Honour (CH) in the 1926 New Year Honours.[5]

In his later years he shared a house with his sister Marie Louise Carlile in Woking.[6] On his death in 1942 his ashes were interred at the foot of his memorial in St Paul's Cathedral.

Veneration

Carlile is honoured with a feast day on the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church (United States) on 26 September.

Remembrance

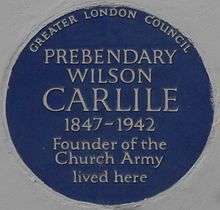

There is a blue plaque on the house where Wilson Carlile lived in Kensington, No. 34 Sheffield Terrace.[7]

A homeless hostel for adult male ex-offenders in Manchester has been named after Wilson Carlile [8]

The current Sheffield head office of Church Army is based in its old training college for evangelists, named for Wilson Carlile.[9]

References

- According to National Archives currency converter, £20,000 in 1870 equates in value to £914,000 in 2005.

- The Times, 28 September 1942 – Carlile's obituary

- Williams, Harry (1980). Booth-Tucker: William Booth's First Gentleman. London: Hodder & Stoughton. pp. 51–52. ISBN 0-340-25027-5.

- "History". St Mary at Hill.

- "No. 33119". The London Gazette (Supplement). 29 December 1925. p. 7.

- Marion Field, Secret Woking, Amberley Publishinh (2017) - Google Books

- "Wilson Carlile Blue Plaque". openplaques.org. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- "Wilson Carlile House". Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- "Wilson Carlile Centre". churcharmy.org. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

History of the Church Army, including some biographical details of Carlile