William Washabaugh

William Washabaugh (born January 14, 1945) is Professor Emeritus of anthropology at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee. He has pursued studies of Creole languages, Sign languages of the Deaf, flamenco artistry, sport fishing, and cinema.

William Washabaugh | |

|---|---|

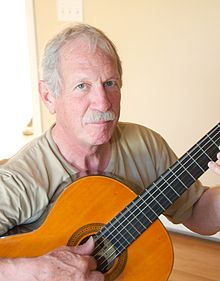

headshot of Dr. William Washabaugh taken May 2009. | |

| Born | January 14, 1945 Monongahela, Pennsylvania |

| Education | Doctorate, Wayne State University, 1974 |

| Occupation | Anthropology professor |

| Years active | 1974-present |

| Employer | University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee |

| Known for | Linguistic anthropology, popular culture studies, flamenco studies |

| Home town | Bethlehem, Pennsylvania |

| Title | Professor Emeritus of Anthropology |

| Website | sites |

Research interests

William Washabaugh has produced works of critical scholarship in linguistics and popular culture. His studies of the Creole language of Providence islanders and of the Sign language of Deaf islanders raised doubts about prevailing views of linguistic variation. Whereas the dominant opinion in studies of Creole variation had emphasized universal constraints, the Providence case, as published in the flagship journal Language (1977), demonstrated that other forces, external to language, bear on that variation. In Five Fingers for Survival: A Deaf Sign Language in the Caribbean (1986), Washabaugh found reasons to question the dominant assumption that the vernacular signing of the Deaf is guided by universal acquisition constraints, again pointing out relevant forces external to the language. These queries and objections culminated in Speak Into the Mirror: A Story of Linguistic Anthropology (1988) which reconsidered the foundational role played by linguistic theory in the development of anthropological thought.

Beyond strictly linguistic issues, Washabaugh explored the social forces that bear on non-verbal expressions and communications. His studies of flamenco artistry in Flamenco: Passion, Politics, and Popular Culture (1996) and Flamenco Music and National Identity in Spain (2012) pointed out that flamenco song and dance are far more responsive to political forces than had been supposed in existing accounts and scholarly description. His study of trout angling in America, Deep Trout: Angling in Popular Culture (2000), made a similar point, namely that casting a fly on a quiet stream is far from being the simple pleasure it is made out to be. It is instead freighted with the weight of class conflict and economic opportunism.

Washabaugh also confronted conventional wisdom in religion and theology. In his Waltzing Porcupines: Community and Communication (2004) he proposed that religious communities (no less than Creole and Deaf communities) and religious practices (no less than flamenco and angling practices) always involve negotiations with external forces. A peaceful prayer is no less illusory than a pure flamenco performance or a sublime trout on the line.

His current project, Silvered Screens: Self in Cinema (forthcoming), pursues a study of more than five hundred movie moments during which characters react to their mirror images. The purpose of this study is to discern how personal identity is handled, how “self” is done. Rather than exploring the ways in which people conceive of their selves, this study inquires into the presuppositions of people who attend to their mirrors, sometimes preening, sometimes wincing, attacking, or even shooting the glass they see. Silvered Screens concludes that self is far from simple; it is fraught with hidden forces, not unlike our everyday performances of speech, sign, music, and angling.

Education

B.A., 1966, St. Bernard's Seminary, Rochester, NY

M.A., 1970, U. of Connecticut Storrs, CT

Ph.D., 1974, Wayne State U., Detroit, MI

Thesis and Dissertation: Puerto Rican Immigrants in Willimantic, CT (M.A.), Variability in Decreolization on Providence Island, Colombia (Ph.D.)

Books

Washabaugh's books include:

- Five Fingers For Survival (Karoma, 1986)[1]

- The Social Context of Creolization (edited with Ellen Woolford, Karoma, 1983)[2]

- Flamenco: Passion, Politics and Popular Culture (Berg, 1996)[3]

- The Passion of Music and Dance: Body, Gender and Sexuality (edited, New York University Press, 1998)[4]

- Flamenco Music and National Identity in Spain (Ashgate, 2012)[5]

Flamenco: Passion, Politics and Popular Culture was a finalist for the 1997 Katharine Briggs Folklore Award.[6]

References

- Reviews of Five Fingers For Survival:

- Kendon, Adam (1987), Nieuwe West-Indische Gids, 61 (1–2): 86–88, JSTOR 41849278CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link)

- Mayberry, Rachel (September 1987), American Anthropologist, New Series, 89 (3): 719–720, JSTOR 678068CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link)

- Supalla, Ted (September 1988), Language, 64 (3): 616–623, doi:10.2307/414536, JSTOR 414536CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link)

- Reagan, Timothy (October 1988), Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 10 (3): 431, JSTOR 44488210CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link)

- Hall, Stephanie A. (September 1989), Language in Society, 18 (3): 453–457, JSTOR 4168070CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link)

- Reviews of The Social Context of Creolization:

- Bickerton, Derek (1984), "Creoles — too much too soon?", Nieuwe West-Indische Gids, 58 (3/4): 207–212, JSTOR 41849173

- Williams, Jeffrey (December 1984), Language, 60 (4): 940–945, doi:10.2307/413807, JSTOR 413807CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link)

- Carrington, Lawrence D. (June 1985), Language in Society, 14 (2): 252–254, JSTOR 4167636CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link)

- Rickford, John; Hancock, Ian (October 1985), Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 7 (3): 343–350, JSTOR 44488566CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link)

- Reviews of Flamenco:

- Bithell, Caroline (1997), British Journal of Ethnomusicology, 6: 203–206, JSTOR 3060840CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link)

- Goldberg, Meira (Fall 1997), Dance Research Journal, 29 (2): 97–101, doi:10.2307/1478739, JSTOR 1478739CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link)

- Volland, Anita (February 1998), American Ethnologist, 25 (1): 38–39, JSTOR 646117CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link)

- Gay y Blasco, Paloma (December 1999), The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 5 (4): 687–688, doi:10.2307/2661215, JSTOR 2661215CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link)

- Reviews of The Passion of Music and Dance:

- Dawe, Kevin (1997), British Journal of Ethnomusicology, 6: 206–211, JSTOR 3060841CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link)

- Burt, Ramsay (Summer 2002), TDR, 46 (2): 176–179, JSTOR 1146970CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link)

- Archetti, Eduardo P. (December 2002), The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 8 (4): 782, JSTOR 3134958CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link)

- Reviews of Flamenco Music and National Identity in Spain:

- "Katharine Briggs Folklore Award 1997: Judges' Report", Folklore, 109: 121, 1998, JSTOR 1260597