William Paston (died 1444)

William Paston (1378 – 13 August 1444), the only son of Clement Paston and Beatrice Somerton, had a distinguished career as a lawyer and Justice of the Common Pleas. He acquired considerable property, and is considered "the real founder of the Paston family fortunes".[1][2]

William Paston | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1378 Paston, Norfolk |

| Died | 13 August 1444 (aged 65–66) London |

| Buried | Norwich Cathedral |

| Spouse(s) | Agnes Barry |

Issue

| |

| Father | Clement Paston |

| Mother | Beatrice Somerton |

Family

William Paston was the only son of Clement Paston (d.1419) and Beatrice Somerton (d.1409). Two decades after William Paston's death it was alleged that the Paston family had descended from serfs.[2] However, during the reign of Edward IV the Pastons were granted a declaration that they were "gentlemen discended lineally of worship blood sithen the conquest hither".[2]

Career

By 1406 William Paston was an attorney in the Court of Common Pleas, and in the ensuing years occupied various legal posts in East Anglia, acting in 1411 as counsel to the city of Norwich and the cathedral priory, and as chief steward to Bishop Richard Courtenay (d.1415), chief steward of Bromholm Priory, and chief steward of Bishop's Lynn. In 1418 he was appointed a Justice of the Peace for Norfolk, and in 1420 was acting as counsel for the Duchy of Lancaster and for the Earl Marshal, John de Mowbray, 2nd Duke of Norfolk. He was executor and feoffee for several gentlemen in East Anglia, and was appointed to numerous Norfolk commissions.[2][3]

He became serjeant-at-law about 1418, and on 15 October 1429 was appointed a Justice of the Common Pleas, a position in which he served until shortly before his death.[2][4]

During his lifetime Paston "put together an imposing estate from the proceeds of office, carrying his family into the front rank of Norfolk landed families".[2] He purchased the manor of Snailwell in Cambridgeshire, but otherwise confined his property acquisitions to Norfolk. Before 1426 he had purchased the manor of Cromer, and in 1427 he purchased the manor of Gresham from Thomas Chaucer.[2][4] In 1418, he and his wife, Agnes, provided funds for the rebuilding of the parish church at Therfield, where they were formerly commemorated by an inscription in the east window of the north aisle.[5]

Paston died at London on 13 August 1444, and was buried at Norwich, in the Lady Chapel of Norwich Cathedral.[2][4] His widow, who was about twenty years of age at the time of her marriage, survived him by thirty-five years, but never remarried. She died on 18 August 1479, and was buried at the Whitefriars, Norwich, with her parents, grandparents, and youngest son, Clement, who had predeceased her.[2][6]

Marriage and issue

In 1420, at the age of forty-two, Paston married Agnes Barry or Berry (d. 18 August 1479), the daughter and coheir of Sir Edmund Barry (d.1433) of Horwellbury, near Therfield and Royston, Hertfordshire,[7] by whom he had four sons and one daughter:[8][2][9][5]

- John Paston (10 October 1421 – 21 or 22 May 1466), who married Margaret Mautby (d.1484), daughter of John Mautby of Mautby,[10] and has issue including two sons both called John, one born in 1442 and one born in 1444.

- Edmund Paston (1425 – c. 21 March 1449), who died without issue.[11]

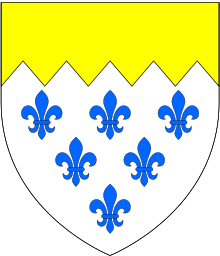

- William Paston (1436 – September 1496), who married Anne Beaufort, third daughter of Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset, by whom he had at least four daughters, one of whom died in childhood. He is credited with having compiled, about 1450, part of the manuscript known as The Paston Book of Arms (NRO, MS Rye 38).[12][13]

- Clement Paston (1442 – c. August 1479), who died without issue.[14]

- Elizabeth Paston (1 July 1429 – 1 February 1488), who married firstly Sir Robert Poynings, slain at the Second Battle of St Albans on 17 February 1461, by whom she had an only son, Sir Edward Poynings, and secondly Sir George Browne of Betchworth Castle (beheaded on Tower Hill 4 December 1483), by whom she had two sons, Sir Matthew and George, and a daughter, Mary.[2][9][15][16]

Letters

Many letters written by William Paston's family and their circle have survived, making the Paston Letters an exceptionally valuable collection of historical documents; the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography has called them "the richest source there is for every aspect of the lives of gentlemen and gentlewomen of the English middle ages".[1]

Notes

- Richmond 2010.

- Richmond & Virgoe 2004.

- Davis 1971, pp. lii–liii.

- Davis 1971, p. liii.

- Jones 1993, p. 81.

- Davis 1971, pp. liii, liv.

- 'Parishes: Kelshall', A History of the County of Hertford: volume 3 (1912), pp. 240–244 Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- Richmond 1990, p. 117.

- Richardson I 2011, p. 340.

- Davis 1971, pp. liv, lvii.

- Davis 1971, p. lvi.

- Davis 1971, p. lvii.

- Norman Davis and G. S. Ivy, "MS Walter Rye 38 and its French Grammar", Medium Ævum, 31 (1962), pp. 112–113.

- Davis 1971, p. lviii.

- Davis 1971, pp. lvi, lvii.

- West 2004, p. 39.

References

- Davis, Norman, ed. (1971). The Paston Letters and Papers of the Fifteenth Century, Part I. Oxford: Clarendon Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, Arthur, ed. (1993). Hertfordshire 1731–1800 As Recorded in The Gentleman's Magazine. Hertford: Hertfordshire University Press. ISBN 0-901354-73-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Richardson, Douglas (2011). Everingham, Kimball G. (ed.). Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families. I (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City. p. 340. ISBN 1449966373.

- Richmond, Colin; Virgoe, Roger (2004). "Paston, William (I) (1378–1444)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21514. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Richmond, Colin (2010). "Paston family (per. c.1420–1504)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/52791. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Richmond, Colin (1990). The Paston family in the Fifteenth Century: The First Phase. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- West, Diane, trans. (2004). The Paston Women. Woodbridge, Suffolk: D.S. Brewer.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- The Paston book of arms c. 1450: NRO, MS Rye 38 Retrieved 2 October 2013