William Mason (locomotive builder)

William Mason (September 2, 1808 – May 21, 1883) was a master mechanical engineer and builder of textile machinery and railroad steam locomotives. He founded Mason Machine Works of Taunton, Massachusetts. His company was a significant supplier of locomotives and rifles for the Union Army during the American Civil War. The company also later produced printing presses.

William Mason | |

|---|---|

William Mason | |

| Born | September 2, 1808 |

| Died | May 21, 1883 (aged 74) |

| Resting place | Taunton, Massachusetts |

| Education | self-taught |

| Occupation | Mechanical Engineer |

| Employer | Mason Machine Works |

| Known for | Mason's Spinning Mule / locomotive builder |

Youth and education

Mason was born in 1808 in Mystic, Connecticut, the son of a blacksmith. As a boy, Mason spent time in his father's shops. He left home at the age of thirteen and worked as an operator in the spinning room of a small cotton factory in Canterbury, Connecticut.[1] He was a born mechanical genius and could repair the most complicated machine in the mill. At the age of sixteen he went to East Haddam, where a mill for the manufacture of thread was being established, to start the machines. At seventeen he worked at the machine shop connected with the mill, where he stayed for three years. It was here he set up the first power loom in the country for the manufacture of diaper linen. He also constructed an ingenious loom for the weaving of damask table cloths.

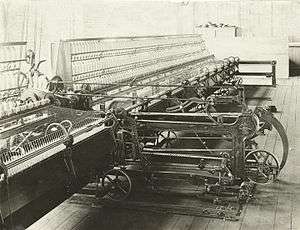

Cotton and weaving machinery

In 1833, Mason joined Asell Lamphaer at Killingly, Connecticut, to make the ring-frame for spinning. He remodeled and perfected the "ring" along with an improved frame.[2]

In 1835, Mason moved to Taunton, Massachusetts, to join Crocker and Richmond, manufacturers of cotton machinery. He worked almost entirely on ring frames. The firm failed in 1837 during the financial crisis. The business was taken over by Messrs Leach and Keith. Mason was employed as foreman. On October 8, 1840, his greatest invention, a "self-acting mule" was patented. Competition required improvements and on October 3, 1846, he received a patent for "Mason's Self-acting Mule." [3]

Though the company would also later venture into the production of locomotives, rifles and printing presses, the production of textile machinery would be its most important sector until the later 19th century.

Mason locomotives

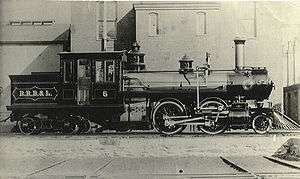

Leach and Keith suffered a failure in the winter of 1842 owing Mason a large amount of money. James K. Mills & Co. of Boston, a leading commission firm, came to his rescue and helped him to buy out the former partners. In 1845, new buildings were erected and the plant became the largest one devoted to the manufacture of machinery in the country. It made cotton machinery, woolen machinery, machinists' tools, blowers, cupola furnaces, gearing, shafting, railroad car wheels made with spokes, and after 1852, locomotives.

Mason wanted to improve the symmetry of the American locomotive. A first engine was turned out in 1853. In 1857 his firm failed but he managed to reopen the plant soon afterwards. The textile business recovered rapidly but the locomotive business was less prosperous. By 1860, he had produced a total of only 100 engines. The figure was doubled by 1865 due to the wartime demand and the pace continued for the next several years. Also during the American Civil War, 600 Springfield rifles were turned out weekly.

Mason's locomotives were genuinely handsome without ornaments. His influence was exerted over all locomotive builders at the time and later. In 1856 he built two locomotives for the Cairo and Alexandria Railroad of Egypt in which a commentator said that the engines' excellence was due to the accuracy of execution attained by an admirable set of tools and a skillful set of workmen. Opinion by master mechanics was that they were the easiest engines to keep in repair. In 1871, the Mason Bogie was introduced.

The business was organized as the Mason Machine Works in 1873 with a capital of $800,000.

Only one of Mason's locomotives survives today in operating condition: the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad's appropriately named #25 "William Mason". It is a 4-4-0 American type engine built in 1856, and is the second oldest operable locomotive in the United States. It is currently on display at the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Museum, and was most recently steamed up in 2012 for the museum's annual B&O Steam Days event. It has been used on screen in several Western movies, most notably The Great Locomotive Chase (1956) and Wild Wild West (1999).

Death and legacy

Mason died May 21, 1883 of pneumonia. He is buried at Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Taunton, Massachusetts. The 700th engine was being completed. Only 54 more engines were completed by 1889 and delivered in 1890. The company continued to build cotton machinery.

William Mason was a painter and a good violinist. He established a bank in Taunton for his employees and made gifts to charity. He is remembered as a pioneer in the building of locomotives which ranked foremost in the country.

References

- Taunton and Mason: Cotton Machinery and Locomotive Manufacture in Taunton, Massachusetts, 1811-1861, by John William Lozier, Ph.D. Dissertation Thesis at Ohio State University 1978. Copies also at Old Colony Historical Society in Taunton and at The Baker Business School Library at Harvard University.

- Mason Machine Works. The Mason Machine Works, Taunton Massachusetts, U.S.A.: Inventors and Builders of Cotton Machinery. Taunton, Mass.: The Company, 1898.

External links

- Photograph of William Mason

- William Mason Papers, 1839 - 1857 Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

- The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography By James Terry White, published 1909 William Mason article Volume 10, Page 386.

- History of Bristol County, Massachusetts: With Biographical Sketches of Many of its Pioneers and Prominent Men, compiled by Duane Hamilton Hurd, published 1883. William Mason article on page 886.

- Investigating Disruptive Technology, The Emergence Of Ring Spinning In The American Textile Industry.