William Jasper

William Jasper (circa 1750 – October 9, 1779) was a noted American soldier in the Revolutionary War. He was a sergeant in the 2nd South Carolina Regiment.

William Jasper | |

|---|---|

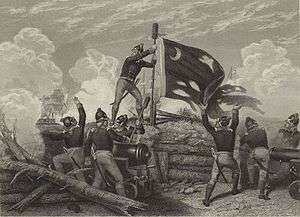

Jasper raises the Moultrie Flag during the Battle of Sullivan's Island | |

| Born | c. 1750 |

| Died | October 9, 1779 Savannah, Georgia |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1775-1779 |

| Rank | Sergeant |

| Unit | 2nd South Carolina Regiment |

| Battles/wars | American Revolutionary War |

Jasper distinguished himself in the defense of Fort Moultrie (then called Fort Sullivan) on June 28, 1776. When a shell from a British warship shot away the flagstaff, he recovered the South Carolina flag in the Battle of Sullivan's Island, raised it on a temporary staff, and held it under fire until a new staff was installed. Governor John Rutledge gave his sword to Jasper in recognition of his bravery.

In 1779, Sergeant Jasper participated in the Siege of Savannah, led by General Lincoln, which failed to recapture Savannah, Georgia, from the British. He was mortally wounded during an assault on the British forces there.

Sgt. Jasper's story is similar to that of Sgt. John Newton. Several states have adjacent counties named Jasper and Newton, as these were remembered as a pair, due to the popularity of Parson Weems' memorializing early American history.[1] Several other states have a Jasper County with a county seat of Newton, or vice versa.

Early life

Sources differ on William Jasper's origins. According to one account, William Jasper (named Johann Wilhelm Gasper at the time) came to America in 1767 on the ship Minerva. He and other immigrants hailed from Germany and landed in Philadelphia. He was 16 at the time, but he had decided that whatever the new land held, he would accept it with open arms.[2]

He arrived in Philadelphia in the fall and was fed some warm soup and then put in a line to take an oath of allegiance and sign his name. When it was his turn, though, Jasper did not know how to read or write, so he could not even write his name on the list. He had to just put an X down where he should have put his name and next to it the colonist who had signed him in wrote John William Jasper. He then completed a few years of indentured servitude and moved south to find some land of his own.[3]

William Jasper was motivated when he settled down in the South; he had left his girlfriend in Pennsylvania. To pay for her journey to come live with him, he joined the military; by this time, the colonists had already rebelled. Although the pay was not great, he soon became a sergeant, earning enough for Elizabeth to join him in Georgia, where they were soon married.

According to other accounts, William Jasper was the son of John Jasper, a Virginia blacksmith who had migrated to Union County, South Carolina during the early 1770s.[4]

Fort Sullivan

Jasper was soon called to Sullivan's Island to help protect Charles Towne (Charleston) Harbor. There, he served under Colonel William Moultrie, who was in charge of the defense of Charleston against the British Navy. A few days before the British were due to arrive, Colonel Moultrie decided to build a fort to protect the harbor. His officers were sent to local plantation owners to borrow their slaves to help with the creation of the fort. Soldiers, slaves, and volunteers banded together to chop down palmettos and use them in its construction.

Initially called Fort Sullivan, some time after the battle the fort was renamed to Fort Moultrie.[5] The British arrived before the fort was finished, its whole back remaining incomplete. The Moultrie flag was raised over the structure, and a 10-hour siege began.

Low on ammunition, the 2nd South Carolina Regiment only fired when ships closed in on the fort. The flag, designed by Moultrie himself at the behest of the colonial government, was shot down, and fell to the bottom of the ditch on the outside of the fort. Leaping from an embrasure, Jasper recovered the flag, which he tied to a sponge staff (see the Cannon instruments section of the Cannon operation article) and replaced on the parapet, where he supported it until a permanent flag staff had been procured and installed.[6] With this rallying point, the colonists held out until sunset, when the British retreated. They did not succeed in taking Charleston until several years later.

Because of Jasper's heroism, Governor John Rutledge presented him with his personal sword, and offered him a lieutenant's commission.[7] He did not accept the offer to become an officer, saying that he would only be an embarrassment since he could neither read nor write. He was also presented with two silk flags by Mrs. Susannah Elliott.

Roving commission

_p785_CHARLESTON%2C_JASPER_MONUMENT.jpg)

Colonel Moultrie gave him a roving commission to scour the country with a few men, gather information, and surprise and capture the enemy's outposts. This commission was later renewed by Francis Marion and Benjamin Lincoln. Prominent among his achievements was the legendary rescue by himself and a single comrade, John Newton, of some American captives from a party of British soldiers whom they overpowered and made prisoners.[5][7] While Jasper did engage in a heroic action against the British, the incident was exaggerated by the storyteller Parson Weems[8]

Savannah

At the Siege of Savannah, he received his death wound while fastening to the parapet the standard which had been presented to his regiment. His hold, however, never relaxed, and he bore the colors to a place of safety before he died.[7]

Places named after Jasper

- Jasper County, Georgia[9]

- Jasper County, Illinois

- Jasper County, Indiana

- Jasper County, Iowa[10]

- Jasper County, Mississippi

- Jasper County, Missouri

- Jasper County, South Carolina

- Jasper County, Texas and the city of Jasper, Texas

- City of Jasper, Alabama

- City of Jasper, Arkansas

- City of Jasper, Florida

- City of Jasper, Georgia

- City of Jasper, Minnesota

- City of Jasper, Missouri

- Town of Jasper, Tennessee

- Town of Jasper, New York

References

- Lou Ann Everett (December 1958). "Myth on the Map". American Heritage. 10 (1): 62–64.

- Idella Bodie (2008). The Man Who Loved the Flag. Heroes and Heroines of the American Revolution (5th ed.). pp. 1–2.

- Idella Bodie (2008). The Man Who Loved the Flag. Heroes and Heroines of the American Revolution (5th ed.). pp. 3–5.

- Mannie Lee Mabry, editor (1981). Union County Heritage. p. 156.

- James W. Patton (1933). "Jasper, William". Dictionary of American Biography. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1892). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- 1958 American Heritage article "Myth on the Map"

- Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. pp. 168.

- Weaver, James Baird (1912). Past and Present of Jasper County, Iowa, Volume 1. B.F. Bowen. p. 44.

External links

- Edward McCrady (1901). The History of South Carolina in the Revolution, 1775-1780. Macmillan. p. 157. Cited by 1920 Americana.

- James Mason Peck [Boone]; Francis Bowen [Lincoln] (1847). Lives of Daniel Boone and Benjamin Lincoln. Boston: C. C. Little and J. Brown. pp. 315–316.

- Alexander Garden (1822). "Sergeant Jasper, 2d Regiment". Anecdotes of the Revolutionary War in America. Published by the author. pp. 90–91.

- DeSoto Hotel and Jasper Monument, Savannah, Ga. postcard from the Historic Postcard Collection, RG 48-2-5, Georgia Archives

- General Casimir Pulaski/Sergeant William Jasper historical marker

- Jasper Spring historical marker