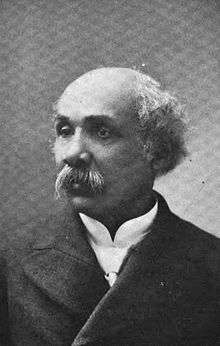

William Hannibal Thomas

William Hannibal Thomas (4 May 1843 – 15 November 1935) was an American teacher, journalist, judge, writer and legislator.

William Hannibal Thomas | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | May 4, 1843 |

| Died | November 15, 1935 |

| Education | Otterbein University Western Theological Seminary |

| Occupation | Teacher, journalist, judge, writer, legislator |

Biography

Early life

William Hannibal Thomas was born in Pickaway County, Ohio. His family had been formerly enslaved, although Thomas insisted that "most of his ancestors were white."[1] In 1859, he was the first black student admitted to Otterbein University.

He served with distinction in the 5th United States Colored Infantry Regiment during the Civil War of 1861-1865, suffering a gunshot wound that led to the amputation of his right arm.[2] After the war, he attended Western Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania.

Career

In 1871, he taught for some time and then he earned a license to practice law in South Carolina in 1873.[1] He worked briefly at Wilberforce University in Ohio. He then served as a member of the South Carolina Legislature during the Reconstruction period. During Reconstruction, he was an open advocate for armed Black self-defense against white supremacist violence.[3]

In 1878, President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed Thomas U.S. consul to Portuguese Southwest Africa (now Angola).[4] Later he founded his own journal, The Negro.

He is now most remembered for The American Negro (1901),[3] a bombastic work brought out by the Macmillan publishing company. In this book, he wrote that it was not skin color but the black population's traits of character and behavior were the cause of prejudice. "The negro", he wrote, was "an intrinsically inferior type of humanity."[5] He declared that the black individual in America was slowly and steadily deteriorating, and was "immersed in poverty, steeped in ignorance, stifled with immorality, inherently lazy, and a born pilferer."[6] His writings were used by white racists to support their own ideas of "white superiority and black inferiority."[1]

Several black intellectuals such as Booker T. Washington,[7] W.E.B. Du Bois[8] and Charles W. Chesnutt,[9][10] attacked the author and sought to suppress his book.[11]

Death

He died in Columbus, Ohio in 1935.

Bibliography

- Land and Education (1890).

- The American Negro (1901).[12]

See also

Notes

- Rabaka, Reiland (2012). Hip Hop's Amnesia: From Blues and the Black Women's Club Movement to Rap and the Hip Hop Movement. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Book. pp. 45–46. ISBN 9780739174920.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, John David (2004). "William Hannibal Thomas, b. 1843," Documenting the American South.

- Smith, John David (2000). Black Judas: William Hannibal Thomas and "The American Negro". Athens: University of Georgia Press.

- Smith, John David (2003). "Thomas, William Hannibal." In: Historical Dictionary of the Gilded Age. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, p. 492.

- The American Negro. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1901, p. 238.

- The American Negro (1901), p. 384.

- Washington, Booker T. (1901). "The American Negro," The Outlook, Vol. 67, pp. 733–736.

- DuBois, W.E.B. (1901). "The Sorm and Stress in the Black World," The Dial, Vol. 30, pp. 262–264.

- Chesnutt, Charles W. (1901). "A Difamer of his Race," The Critic, Vol. 38, pp. 350–351.

- Thomas, William Hannibal (1901). "Mr. William Hannibal Thomas Defends his Book," The Critic, Vol. 38, pp. 548–550.

- Smith (2000), p. 212.

- "More About the American Negro," The Book Buyer, Vol. 22, 1901, pp. 143–144.

Further reading

- Bracey, Earnest N. (2005). "Analysis of a Racial Parasite: Black Judas: William Hannibal Thomas and the American Negro." In: Places in Political Time: Voices from the Black Diaspora. University Press of America, pp. 40–49.

- Councill, W.H. (1902). "The American Negro: An Answer," Publications of the Southern History Association, Vol. 6, pp. 40–44.

- Luker, Ralph E. (1998). "Theologies of Race Relations." In: The Social Gospel in Black and White: American Racial Reform, 1885-1912. University of North Carolina Press, pp. 268–311.

- McElrath, Joseph, ed. (1997). To Be an Author: Letters of Charles Chesnutt, 1889-1905. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Smith, John David (2003). "The Lawyer vs. the Race Traitor: Charles W. Chesnutt, William Hannibal Thomas, and The American Negro," Journal of The Historical Society, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 225–248.