William Galbraith (mathematician)

Rev William Galbraith (1786 – 27 October 1850) was a Scottish mathematician. He taught mathematics and nautical astronomy in Edinburgh, and took an interest in surveying work, becoming an advocate of the extension of the work of triangulating Great Britain.[1]

Early life

He was born at Greenlaw, Berwickshire.[2] Initially he was a schoolmaster. His pupil William Rutherford walked long distances to attend his school at Eccles. Subsequently he moved to Edinburgh, and graduated A.M. at the University of Edinburgh in 1821.[3]

Surveyor

During the 1830s Galbraith became interested in the surveying problems of Scotland. In 1831 he pointed out that Arthur's Seat had a strongly magnetic peak.[4] In 1837 he pointed out the impact of anomalies in measurement, work that received recognition;[5] it was topical because of the 1836 geological map of Scotland by John MacCulloch, with which critics had found fault on topographical as well as geological grounds.[6] A paper on the locations of places on the River Clyde was recognised in 1837 by a gold medal, from the Society for the Encouragement of the Useful Arts for Scotland.[7]

Galbraith followed with detailed Remarks on the Geographical Position of some Points on the West Coast of Scotland (1838).[8] Having made some accurate surveys of his own, he lobbied for further attention from the national survey.[1]

Later life

About 1832 Galbraith was licensed a minister by the presbytery of Dunse. He married Eleanor Gale in 1833.[3]

Galbraith was buried with his wife in the north-east section of the Grange Cemetery in Edinburgh.[9]

Works

Galbraith's major works combined textbook material with mathematical tables:

- Mathematical and Astronomical Tables (1827):[10] review.[11]

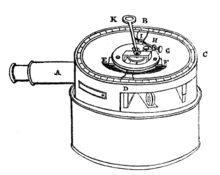

- Trigonometrical Surveying, Levelling, and Railway Engineering (1842)[12]

He edited John Ainslie's 1812 treatise on land surveying (1849),[13] and with William Rutherford revised John Bonnycastle's Algebra.[14]

Notes

- http://articles.adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1851MNRAS..11...86.

- Royal Astronomical Society (1851). Memoirs. Society. pp. 194–. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- http://www20.us.archive.org/stream/topographicalsta01edinuoft#page/n145/mode/2up

- (in German) http://www26.us.archive.org/stream/almanachderkais03wiengoog#page/n654/mode/2up

- Cumming, David A. "MacCulloch, John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/17412. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- The Edinburgh Philosophical Journal. Constable. 1837. pp. 1–. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- The Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal. A. and C. Black. 1838. pp. 300–. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- https://archive.org/stream/monumentsmonumen01rogeiala#page/152/mode/2up

- William Galbraith (1827). Mathematical and Astronomical Tables. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- Robert Jameson; Sir William Jardine; Henry Darwin Rogers (1827). The Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal: exhibiting a view of the progressive discoveries and improvements in the sciences and the arts. A. and C. Black. pp. 404–. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- https://archive.org/stream/trigonometrical00galbgoog#page/n6/mode/2up

- https://archive.org/details/atreatiseonland00ainsgoog

- . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.